Eurogame

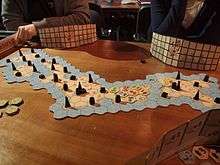

A Eurogame, also called a German-style board game, German game, or Euro-style game, is a class of tabletop games that generally have indirect player interaction and abstract physical components. Euro-style games emphasize strategy while downplaying luck and conflict. They tend to have economic themes rather than military and usually keep all the players in the game until it ends.

Eurogames are sometimes contrasted with American-style board games, which generally involve more luck, conflict, and drama.[1][2]

Eurogames are usually less abstract than chess or Go, but more abstract than wargames. Likewise, they generally require more thought and planning than party games such as Pictionary or Trivial Pursuit.

Definition and variations

Eurogame is a common, though still an imprecise, label. Because most of these games feature the name of the designer prominently on the box, they are sometimes known as designer games.[3] Other names include German Style Boardgame, family strategy game and hobby game. Shorter, lighter games in this class are known as gateway games, whereas longer, heavier games are known as gamers' games.[4]

History

Contemporary examples of modern board games referred to as "eurogames", such as Acquire, appeared in the 1960s. The 3M series of which Acquire formed a part became popular in Germany, and became a template for a new form of game, one in which direct conflict or warfare did not play a role, due in part to aversion in postwar Germany to products which glorified conflict.[5][6] The genre developed as a more concentrated design movement in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Germany, and as of 2009 Germany purchased more board games per capita than any other country.[7] The phenomenon has spread to other European countries such as France, the Netherlands, and Sweden. While many games are published and played in other markets such as the United States and the United Kingdom, they occupy a niche status there.[7]

The Settlers of Catan, first published in 1995, paved the way for the genre outside Europe.[8] Though neither the first eurogame nor the first such game to find an audience outside Germany, it became much more popular than any of its predecessors. It quickly sold millions of copies in Germany, and in the process brought money and attention to the genre as a whole. Other games in the genre to achieve widespread popularity include Carcassonne, Puerto Rico, Ticket to Ride, and Alhambra.

Characteristics

Eurogames are usually multiplayer and can be learned easily and played in a relatively short time, perhaps multiple times in a single session. A certain amount of socializing might typically be expected during game play, as opposed to the relative silence sometimes expected during some strategy games like chess and go or restrictions on allowable conversations or actions found in some highly competitive games such as contract bridge.

Eurogames also differ from abstract strategy games like chess by using themes tied to specific locales, and emphasize individual development and comparative achievement rather than direct conflict.[5] Eurogames also emphasize the mechanical challenges of their systems over having the systems match the theme of the game. They are generally simpler than the wargames that flourished in the 1970s and 1980s from publishers such as SPI and Avalon Hill, but nonetheless often have a considerable depth of play, especially in some "gamers' games" such as Tigris and Euphrates and Caylus.

One consequence of the increasing popularity of this genre has been an expansion upwards in complexity. Games such as Puerto Rico that were considered quite complex when Eurogames proliferated in the U.S. after the turn of the millennium are now the norm, with newer high-end titles like Terra Mystica and Tzolkin being significantly more difficult to master.

Themes

Eurogames tend to have a theme (role-play element or a background story)—more like Monopoly or Clue, rather than poker or Tic Tac Toe. Game mechanics are not restricted by the theme, however; unlike a simulation game, the theme of a Eurogame is often merely mnemonic. It is somewhat common for a game to be designed with one theme and published with another, or for the same game to be given a significantly different theme for a later republication, or for two games on wildly different themes to have very similar mechanics. Combat themes are uncommon, and player conflict is often indirect (for example, competing for a scarce resource).

Example themes are:

- Carcassonne – build a medieval landscape complete with walled cities, monasteries, roads, and fields.

- Puerto Rico – develop a plantation on the island of Puerto Rico, set in the 18th century.

- Imperial – as an international investor, influence the politics of pre-World War I European empires.

- Bruxelles 1893 – take the role of an Art Nouveau architect during the late 19th century and try to become the most famous architect in Belgium.[9]

Games made for everyone

While many titles (especially the strategically heavier ones) are enthusiastically played by gamers as a hobby, Eurogames are, for the most part, well suited to social play. In keeping with this social function, various characteristics of the games tend to support that aspect well, and these have become quite common across the genre. For example, generally Eurogames do not have a fixed number of players like chess or bridge; though there is a sizable body of German-style games that are designed for exactly two players, most games can accommodate anywhere from two to six players (with varying degrees of suitability). Six-player games are somewhat rare, or require expansions, as with The Settlers of Catan or Carcassonne. Usually each player plays for him- or herself, rather than in a partnership or team.

Playing time varies from a half-hour to a few hours, with one to two hours being typical. In contrast to games such as Risk or Monopoly, in which a close game can extend indefinitely, Eurogames usually have a mechanism to stop the game within its stated playing time. Common mechanisms include a pre-determined winning score, a set number of game turns, or depletion of limited game resources. For example, Ra and Carcassonne have limited tiles to exhaust.

Low randomness

Eurogame designs tend to de-emphasize luck and random elements.[10] Often, the only random element of the game will be resource or terrain distribution in the initial setup, or (less frequently) the random order of a set of event or objective cards. The role played by deliberately random mechanics in other styles of game is instead fulfilled by the unpredictability of the behavior of other players.

No player elimination

Another prominent characteristic of these games is the lack of player elimination. Eliminating players before the end of the game is seen as contrary to the social aspect of such games. Most of these games are designed to keep all players in the game as long as possible, so it is rare to be certain of victory or defeat until relatively late in the game.

Related to no-player-elimination is that Eurogame scoring systems are often designed so that hidden scoring or end-of-game bonuses can catapult a player who appears to be in a lagging position at end of play into the lead. A second-order consequence is that Eurogames tend to have multiple paths to victory (dependent on aiming at different end-of-game bonuses) and it is often not obvious to other players which strategic path a player is pursuing.

Balancing mechanisms are often integrated into the rules, giving slight advantages to lagging players and slight hindrances to the leaders. This helps to keep the game competitive to the very end.

International audience

These games are designed for international audiences, so they are not word games and usually do not contain much text outside of the rules. Game components often use symbols and icons instead of words, reducing the amount of text to be translated between localized editions. Gameplay also tends to de-emphasize or entirely exclude verbal communication as a game element, with many games being fully playable if all players know the rules, even if they do not speak a common language.

Some publishers design games that contain instructions and game elements in more than one language, e.g. the game Ursuppe comes with rules and cards in both German and English; Khronos features instructions in French, English, and German, and a Swiss game, Enchanted Owls, provides French, German, Italian, and Romansh rules. However, this is usually not the case if the rights to sell the game outside its country of origin are sold to another publisher.

English editions are often available, either published in the US or co-published by a German company cooperating with a US company, or the reverse (example: Dominion).

Game mechanics

A wide variety of often innovative mechanisms or mechanics are used, and familiar mechanics like rolling dice and moving, capture, or trick taking are avoided. If a game has a board, the board is usually irregular rather than uniform or symmetric (like Risk rather than chess or Scrabble); the board is often random (like The Settlers of Catan) or has random elements (like Tikal). Some boards are merely mnemonic or organizational and contribute only to ease of play, like a cribbage board; examples of this include Puerto Rico and Princes of Florence. Random elements are often present, but do not usually dominate the game. While rules are light to moderate, they allow depth of play, usually requiring thought, planning, and a shift of tactics through the game and often with a chess- or backgammon-like opening game, middle game, and end game.

Stuart Woods' Eurogames cites six examples of mechanics common to eurogames:[5]

- Tile Placement – spatial placement of game components on the playing board.

- Auctions – includes open and hidden auctions of both resources and actions from other players and the game system itself.

- Trading/Negotiation – not simply trading resources of equivalent values, but allowing players to set markets.

- Set Collection – collecting games resources in specific groups that are then cashed in for points or other currency.

- Area Control – also known as area majority or influence, this involves controlling a game element or board space through allocation of resources.

- Worker Placement or Role Selection – players choose specific game actions in sequential order, with players disallowed from choosing a previously selected action.

Game designer as author

Although not relevant to actual play, the name of the game's designer is often prominently mentioned on the box, or at least in the rule book. Top designers enjoy considerable following among enthusiasts of Eurogames. For this reason, the name "designer games" is often offered as a description of the genre.[3] Recently, there has also been a wave of games designed as spin-offs of popular novels, such as the games taking their style from the German bestsellers Der Schwarm and Tintenherz.

Industry

Designers

Designers of Eurogames include:

- Antoine Bauza is a prolific French designer, best known for his work on 7 Wonders.

- Vlaada Chvátil is a Czech designer of board games and video games, whose games include Through the Ages: A Story of Civilization, Galaxy Trucker, and Space Alert. He is well known for his unusual rule books, which are often divided into several "learning scenarios" that gradually introduce players to the rules as they progress through the scenarios.

- Leo Colovini is best known for his board games Cartagena and Carcassonne: The Discovery.

- Stefan Feld is known for games that make ingenious use of dice,[11] and has designed games such as Castles of Burgundy and Trajan, and has been nominated for the Spiel des Jahres.

- Friedemann Friese is a German designer, best known for Power Grid, as well as many others.

- Reiner Knizia is one of the most well-known & prolific German game designers, having designed over 200 published games. Recurring mechanisms in his games include auctions (Ra and Modern Art), tile placement (Tigris and Euphrates and Ingenious), and intricate scoring rules (Samurai). He has also designed many card games such as Lost Cities, Schotten-Totten, and Blue Moon, and the cooperative board game The Lord of the Rings.

- Wolfgang Kramer often works with other game designers. Some of his best-known titles include El Grande, Tikal, Princes of Florence, and Torres. His games often have some sort of action point system, and include some geometric element.

- Alan R. Moon is a British-born designer with numerous games to his credit, often with a railway theme, including the Spiel des Jahres winning Ticket to Ride and Elfenland. His games are often characterized by selecting a single action from a choice of several (e.g. gather new cards or use existing cards)

- Alex Randolph created over 125 games and is responsible for the placement of the author's name on the rules and box.

- Uwe Rosenberg designed Agricola, a highly ranked game on BoardGameGeek, as well as Bohnanza, Le Havre, and several others.

- Sid Sackson was a prolific American game designer whose games prefigured and strongly influenced the Eurogame genre.[5]

- Andreas Seyfarth has designed the award-winning games Manhattan, Puerto Rico, and, with Karen Seyfarth, Thurn and Taxis.

- Klaus Teuber has designed a small number of games, many of which became extremely popular. Some have won the Spiel des Jahres Award. Titles include The Settlers of Catan and Adel Verpflichtet.

- Klaus-Jürgen Wrede, the German game designer of the popular Carcassonne board game series. As of September 2014, Carcassonne, has 9 major expansions as well as numerous mini-expansions.

Publishers

There are many German companies producing board games, such as Hans im Glück and Goldsieber. Often German producers will try to establish a line of similar games, such as Kosmos's two-player card game series or Alea's big box line.

The rights to sell the game in English are often sold to separate companies. Some try to change the game as little as possible, such as Rio Grande Games. Others, including Mayfair Games, substantially change the visual design of the game, and sometimes the rules as well.

Events

The Internationale Spieltage, also known as Essen Spiel, or the Essen Games Fair, is the largest non-digital game convention in the world,[5][12] and the place where the largest number of eurogames are released each year. Founded in 1983 and held each fall in Essen, Germany, the fair was founded with the objective of providing a venue for people to meet and play board games, and show gaming as an integral part of German culture.

A "World Boardgaming Championships" is held annually in July in Pennsylvania, USA. The event is nine days long and includes tournament tracks of over a hundred games; while traditional wargames are played there, all of the most popular tournaments are Eurogames and it is generally perceived as a Eurogame-centered event. Attendances is international, though players from the U.S. and Canada predominate.

Awards

The most prestigious German board game award is the Spiel des Jahres ("game of the year").[5][13] The award is very family-oriented. Shorter, more approachable games such as Ticket to Ride and Elfenland are usually preferred by the committee that gives out the award.

In 2011, the jury responsible for the Spiel des Jahres created the Kennerspiel des Jahres, or connoisseur's game of the year, for more complex games.[5]

The Deutscher Spiele Preis ("German game prize") is also awarded to games that are more complex and strategic, such as Puerto Rico. However, there are a few games with broad enough appeal to win both awards: The Settlers of Catan (1995), Carcassonne (2001), Dominion (2009).

Influence

Xbox Live Arcade has included popular games from the genre, with Catan being released to strong sales[14] on May 13, 2007, Carcassonne being released on June 27, 2007.[15] Lost Cities and Ticket to Ride soon followed. Alhambra was due to follow later in 2007 until being cancelled.

The iPhone has received versions of The Settlers of Catan and Zooloretto in 2009. Carcassonne was added to the iPhone App Store in June 2010. Later, Ticket to Ride was developed for both the iPhone and the iPad (boosting sales of the board game tremendously[16]).

See also

- BoardGameGeek

- BrettspielWelt

- Cooperative board game

- Going Cardboard (Documentary about German-style board games and their community)

- List of game designers

References

- ↑ "German recreation: An affinity for rules?" The Economist, August 28, 2008.

- ↑ Jonathan Kay (January 21, 2018). "The Invasion of the German Board Games". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- 1 2 Bob Schwartz. "One Retailer's Perspective".

- ↑ "Glossary". Board Game Geek. BoardGameGeek. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Woods, Stuart (2009). Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games. McFarland. ISBN 0786467975.

- ↑ Donovan, Tristan (2017). It's All a Game: The History of Board Games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 1250082722.

- 1 2 Curry, Andrew (23 March 2009). "Monopoly Killer: Perfect German Board Game Redefines Genre". archive.wired.com. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ Harford, Tim (17 July 2010). "Why we still love board games". ft.com. FT Magazine. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ "Bruxelles 1893 Review – An Art Nouveau & Architecture Board Game".

- ↑ Stevens, DJ (2017-09-13). "Abandoning the screen for cardboard".

- ↑ Casey, Matt (2 October 2014). "Making better use of dice in games". Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ Seemy Peerutin. "Board games are quietly, nerdily, becoming big business".

- ↑ Tinsman, Brian (2008). The Game Inventor's Guidebook: How to Invent and Sell Board Games, Card Games, Role-Playing Games, & Everything in Between!. Morgan James Publishing. ISBN 1600374476.

- ↑ Xbox Live's Major Nelson: Xbox Live Activity for week of 4/30 "Xbox Live Activity for week of 4/30" MajorNelson.com

- ↑ Porcaro, John (2007-06-25). "Build a Medieval Empire on Xbox LIVE Arcade with the Popular German Board Game Carcassonne". Archived from the original on 2007-07-01.

- ↑ Days of Wonder CEO explains how iPad Ticket to Ride boosted sales of the real thing

External links

- Brett and Board with information on German-style games (has not been updated in some time)

- Luding.org – board game database with over 15,000 English and German reviewed games

- BoardGameGeek – internet database of over 100,000 tabletop games, with online fan community.

- Gamerate.net – internet database of board, card and electronic games.