Etheldred Benett

| Etheldred Benett | |

|---|---|

| Born |

22 July 1776 Tisbury, Wiltshire |

| Died |

11 January 1845 (aged 68) Norton House, Norton Bavant |

| Resting place | Bavant Parish Church |

| Occupation | Fossil collector · Geologist |

| Parent(s) |

Thomas Benett (c. 1729–1797) Catherine née Darell d. 1790 |

Etheldred Benett (July 22, 1776 – January 11, 1845) was an early English geologist often credited with being the "First Female Geologist". Benett devoted much of her life collecting and studying fossils that she discovered in South West England. Etheldred Benett’s fossil collection was considered one of the largest at the time. She worked closely with many principal geologists of the time and her fossil collection played a part in the development of geology as a field of science. Gideon Mantell, discoverer of the Iguanadon, was so inspired by Benett's work he named a Cretaceous sponge after her called the "hoplites benettianus".[1]

Early life

Etheldred Benett was born into a wealthy family as the eldest daughter of Thomas Benett (1729–1797) of Wiltshire and Catherine née Darell (d. 1790); her brother, John (1773–1852), was a member of Parliament for Wiltshire and later South Wiltshire from 1819 to 1852. From 1802 she resided at Norton House in Norton Bavant, near Warminster, in Wiltshire. Very little is known about Benett’s private home life, mostly what is known about her is just in her studying and contributions to geology. Also, there is no known portrait of Etheldred. From at least 1809 until her death devoted herself to collecting and studying the fossils of her native county. Benett had mostly stayed within Warminister where she began her collection. Furthermore, Benett was familiar with where the fossils she was finding where located and she was knowledgeable in stratigraphy, and she thought she was able to know where else the fossils that she found could be located elsewhere. Etheldred's interest in geology was encouraged by her sister in-law's half brother, the botanist Aylmer Bourke Lambert.[1][2] Lambert was an avid fossil collector who contributed to Sowerby’s Mineral Conchronoly. He was also a founding member of the Linnean Society, a member of the Royal Society, and an earlier member of the Geological Society. It was through Lambert that Benett developed her love of fossils and relationships with many leading geologists of the time and it is only through works by these men, that most reference to her work was made. For example, Benett contributed to Gideon Mantell with his work on stratigraphy. Also, Benett worked with Sowerby and contributed his work also. Thus, Bennett was acknowledged by famous geologist of the time. Benett was unmarried and financially independent, and so was able to dedicate much of her life to the developing field of science and geology through the collection and study of fossils. Occasionally, Benett was an electioneer for her brother John. Yet, Benett was mainly focusing on discovering and investigating for palaeontology, and geology. As a women of the time Benett did not receive a higher education and was not accepted to scholarly societies. Her wealth at the time assisted Benett’s collection of specimens through the hiring of collectors and the purchase of prepared specimens.

Fossil collection

Benett's speciality was in the Middle Cretaceous Upper Greensand in the Vale of Wardour. Her collection was one of the largest and most diverse of its time resulting in many visitors to her home. Some fossils within her collection were the first to be illustrated and described whilst some were extremely rare or incredibly well preserved.[3] Benett had contact with many authors of fossil works including the Sowerbys. Forty-one of her specimens were included in Sowerby's Mineral Conchology, a major fossil reference work, which contained the second highest number of contributed fossils in which many were the best quality available at the time.[3] After viewing part of her collection, and assuming she was male, Tsar Nicholas I granted her a Doctorate of Civil Law from the University of St. Petersberg at a time when women were not admitted into higher education institutions.[1] As an early female geologist and as a response to her honorary doctorate, Benett noted that "scientific people in general have a very low opinion of the abilities of my sex."[1]

Most of her fossil collection is currently housed at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia after purchase by Thomas Bellerby Wilson. Although, small parts are in many British museums, in particular Leeds City Museum and possibly even in St. Petersburg. These collections contain many type specimens and some of the first fossils found (and recognized though shortly after her death) with the soft tissues preserved.[4]

Benett's entire collection was assumed lost in the early 20th century due to specific specimens that were unable to be located. However, the ANSP’s revived interest in the early English fossil collections, and furthermore Benetts collection, led to formal recognition again. This ultimately led to the discussion of her previous two publications, the elaboration of her taxonomic names, and the photographic illustration of many vital pieces of her collection.

Benett also had an interest in conchology and as well as her fossil collection, spent time collecting and detailing shells, many of which were new records. In a letter to Mantell in 1817, she claimed her shell collecting had left her with no time to look at his fossils.[3]

Accomplishments

Her unusual first name caused many to suppose that she was a man. This mistake was detected when the Natural History Society of Moscow awarded membership to her under the name of Master Etheldredus Benett in 1836. [5] This was evident once again when she was granted the Doctorate of Civil Law by Tsar Nicholas I. This doctorate was given to her from the University of St Petersburg at a time when women were not allowed to be accepted into higher institutions. [6]

Contribution to geology and palaeontology

Benett’s contribution to the early history of Wiltshire geology is significant as she felt at ease and corresponded extensively with fellow geologists such as George Bellas Greenough, first president of the Geological Society, Gideon Mantell, William Buckland, and Samuel Woodward. Perhaps her unique position allowed her to take ideas of “laymen” like William Smith. She freely gave her ideas and items from her fossil collection to worthy causes such as museums, later including sending one to St. Petersburg. On exchanging numerous fossils with Mantell, a thorough understanding of the Lower Cretaceous sedimentary rocks of Southern England was reached.[3]

Her work was recognised and appreciated by notable individuals of the time. Gideon Mantell described her as 'A lady of great talent and indefatigable research,'[3] whilst the Sowerbys note her 'labours in the pursuit of geological information have been as useful as they have been incessant.'

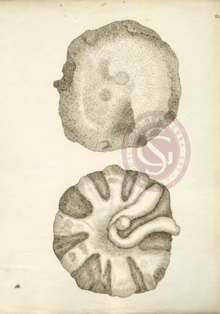

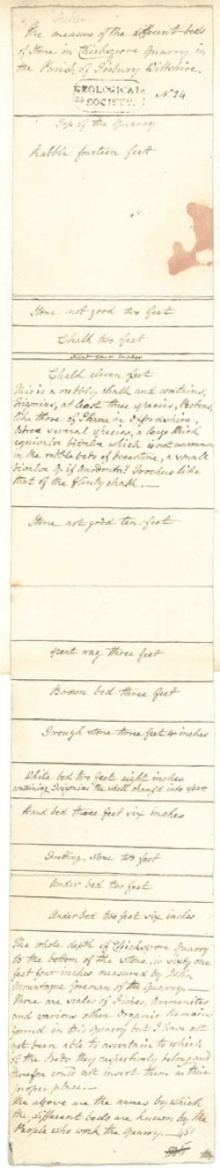

Benett produced the first measured sections of the Upper Chicksgrove quarry near Tisbury in 1819, which is drawn to scale, but unfortunately there is no scale indicated on the section. She calls it, “the measure of different beds of stone in Chicksgrove Quarry in the Parish of Tisbury.” However, the stratigraphic section was published by naturalist James Sowerby without her knowledge. In result, she contradicted some of the Sowerby’s conclusion based on her own research. In 1825, her painting of the meteorite which fell from the County Limerick in September 1813 was deposited in Geological Society of London archives which was presented in the University of Oxford by Reverend John Griffiths of Bishopstrow. The meteorite is 19 pounds in weight, and the streaked and dotted part represents the fracture. Because of her extensive collection, she wrote and privately published a monograph in 1831, which contains many of her drawings and sketches of mollusca and sponges such as her sketches of fossil Alcyonia (1816) from the Green Sand Formation at Warminster Common and the immediate vicinity of Warminster in Wiltshire. The Society holds two copies, one was given to George Bellas Greenough, and another copy was given to her friend Gideon Mantell. This work established her as a true, pioneering biostratigrapher following but not always agreeing with the work of William Smith.

Later life

Illness during the last twenty years of Benett's life meant she spent less time collecting specimens and instead commissioned local collectors. After spending 34 years gathering what was the most extensive collection of Wiltshire fossils, Benett died at her home Norton House at the age of 69, two years before fellow fossil collector Mary Anning. Her fossil collection was later sold to physician Thomas Wilson of Newark, Delaware, who donated the collection to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia .[1]

Works

- A catalogue of the organic remains of the county of Wiltshire, 1831.

- A brief enquiry into the antiquity, honour and estate of the name and family of Wake, 1833 (written by her great grandfather William Wake, Archbishop of Canterbury, but prepared for publication and footnoted by Etheldred Benett)

References

- 1 2 3 4 Burek, Cynthia V (2001). "The first lady geologist, or collector par excellence?". Geology Today. 17 (5): 192–194. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2451.2001.00008.x.

- ↑ Torrens, H. S. (May 2009). "Benett, Etheldred (1775–1845)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cleevely, R J (2004). "Miss Etheldred Benett (1775-1845): A Preliminary Note on her Correspondence". Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine. 97: 25–34.

- ↑ Torrens, Hugh S.; Benamy, Elana; Daeschler, Edward B.; Spamer, Earle E.; Bogan, Arthur E. (2000), Etheldred Benett of Wiltshire, England, the first lady geologist: her fossil collection in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, and the rediscovery of "lost" specimens of Jurassic Trigoniidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia) with their soft anatomy preserved., Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 150, pp. 59–123, JSTOR 4065063, 2010-10-09

- ↑ N/A, N/A. "Etheldred Benett (1775-1845)". The Geological Society. Geological Society of London. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ SARAH. "The road to Fellowship – the history of women and the Geological Society". Geological Society of London. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

Sources

- Spamer, Earle E.; Bogan, Arthur E.; Torrens, Hugh S. (1989). "Recovery of the Etheldred Benett Collection of fossils mostly from Jurassic-Cretaceous strata of Wiltshire, England, analysis of the taxonomic nomenclature of Benett (1831), and notes and figures of type specimens contained in the collection". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 141. pp. 115–180. JSTOR 4064955.

- Torrens, H. S.; Benamy, Elana; Daeschler, E.; Spamer, E.; Bogan, A. (2000). "Etheldred Benett of Wiltshire, England, the First Lady Geologist: Her Fossil Collection in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, and the Rediscovery of "Lost" Specimens of Jurassic Trigoniidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia) with Their Soft Anatomy Preserved.". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 150. pp. 59–123. JSTOR 4064955.

Further reading