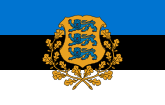

Flag of Estonia

| |

| Name | Sinimustvalge |

|---|---|

| Use |

Civil and state flag, civil ensign |

| Proportion | 7:11[1] |

| Adopted |

21 November 1918 7 August 1990 |

| Design | A horizontal triband of blue, black and white |

Variant flag of Estonia | |

| Use |

Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 7:13 |

| Adopted | 1991 |

| Design | Tricolor, swallowtail, defaced with the shield of the state arms off-set towards hoist. |

The national flag of Estonia (Estonian: Eesti lipp) is a tricolour featuring three equal horizontal bands of blue (top), black, and white. The normal size is 105 by 165 centimetres (41 in × 65 in).[1] In Estonian it is colloquially called the "sinimustvalge" (literally "blue-black-white"), after the colours of the bands.

First adopted on 21 November 1918 after its independence, it was used as a national flag until 1940 when the Soviet Union and Germany occupied Estonia. After World War II, from 1944 to 1990, the Soviet Estonian flag consisted first of a generic red Soviet flag with the name of the republic, then changed to the red flag with a band of blue water waves near the bottom. The Estonian flag, which was also used by the Estonian government-in-exile, was officially re-adopted 7 August 1990 one year before its official restoration of independence.

History

.svg.png)

The story of the flag begins 17 September 1881, when the constituent Assembly of the first Estonian national student Corps "Vironia" (modern Estonian Students Society) in the city of Tartu was also identified in color, later became national.[3]

Independence

The flag became associated with Estonian nationalism and was used as the national flag (riigilipp) when the Estonian Declaration of Independence was issued on February 24, 1918. The flag was formally adopted on November 21, 1918. December 12, 1918, was the first time the flag was raised as the national symbol atop of the Pikk Hermann Tower in Tallinn.[4]

Soviet occupation

The invasion by the Soviet Union in June 1940 led to the flag's ban. It was taken down from the most symbolic location, the tower of Pikk Hermann in Tallinn, on June 21, 1940, when Estonia was still formally independent. On the next day, 22 June, it was hoisted along with the red flag. The tricolour disappeared completely from the tower on July 27, 1940, and was replaced by the flag of the Estonian SSR.

German occupation

During the German occupation from 1941 until 1944, the flag was accepted as the ethnic flag of Estonians but not the national flag. After the German retreat from Tallinn in September 1944, the Estonian flag was hoisted once again.

Second Soviet occupation

When the Red Army arrived on 22 September 1944, the red flag was just added at first. Soon afterwards, however, the blue-black-white flag disappeared. In its place from February 1953, the Estonian SSR flag was redesigned to include the six blue spiked waves on the bottom with the hammer and sickle with the red star on top.

.jpg)

The flag remained illegal until the days of perestroika in the late 1980s. 21 October 1987 was the first time when Soviet forces didn't take down the flag at a public event. 24 February 1989 the blue-black-white flag was again flown from the Pikk Hermann tower in Tallinn. It was formally re-declared as the national flag on 7 August 1990, little over a year before Estonia regained full independence.

Symbolism

A symbolism-interpretation made popular by the poetry of Martin Lipp says the blue is for the vaulted blue sky above the native land, the black for attachment to the soil of the homeland as well as the fate of Estonians — for centuries black with worries, and white for purity, hard work, and commitment.[5]

Other current flags

Historical flags

Flag of the Estonian Governorate within the Russian Empire (1721-1918)

Flag of the Estonian Governorate within the Russian Empire (1721-1918) Flag of the Livonian Governorate within the Russian Empire (1721-1918)

Flag of the Livonian Governorate within the Russian Empire (1721-1918).svg.png) Flag of the Estonian SSR under the Soviet Union (1940-1953)

Flag of the Estonian SSR under the Soviet Union (1940-1953) Flag of the Estonian SSR under the Soviet Union (1953-1990)

Flag of the Estonian SSR under the Soviet Union (1953-1990)

Colours

The shade of blue is defined in the Estonian flag law as follows:

Selections from the Estonian Flag Act

The most recent Estonian Flag Act was passed 23 March 2005 and came into force on 14 June 2014. The Act specifies the colors in Pantone and CMYK formats, as well as specifying when it can be hoisted and how it can be used and by whom. The Act specifies that the flag is "the ethnic and the national flag".[6]

More specifically, the Flag Act specifies that the flag be hoisted on the Pikk Hermann tower in Tallinn every day at sunrise, but not earlier than 7.00 a.m., and is lowered at sunset".[6] The lawful flag days are as follows:

- 3 January – Commemoration Day of Combatants of the Estonian War of Independence

- 2 February – Anniversary of Tartu Peace Treaty

- 24 February – Independence Day

- 14 March – Mother Tongue Day

- 23 April – Veterans’ Day

- The second Sunday of May – Mothers’ Day

- 9 May – Europe Day

- 4 June – Flag Day

- 14 June – Day of Mourning

- 23 June – Victory Day

- 24 June – Midsummer Day

- 20 August – Day of Restoration of Independence

- 1 September – Day of Knowledge

- The third Saturday of October – Finno-Ugric Day

- The second Sunday of November – Fathers’ Day

- The day of election of the Riigikogu[6]

Nordic flag proposals

In 2001, politician Kaarel Tarand suggested that the flag be changed from a tricolour to a Scandinavian-style cross design with the same colours.[7] Supporters of this design claim that a tricolour gives Estonia the image of a post-Soviet or Eastern European country, while a cross design would symbolise the country's links with Nordic countries. Several Nordic cross designs were proposed already in 1919, when the state flag was officially adopted, three of which are shown here. As the tricolour is considered an important national symbol, the proposal did not achieve the popularity needed to modify the national flag.

Advocates for a Nordic flag state that Estonians consider themselves a Nordic nation rather than Baltic,[8] based on their cultural and historical ties with Sweden, Denmark and particularly Finland. In December 1999 Estonian foreign minister—later the Estonian president from 2006 to 2016—Toomas Hendrik Ilves delivered a speech entitled "Estonia as a Nordic Country" to the Swedish Institute for International Affairs.[9] Diplomat Eerik-Niiles Kross also suggested changing the country's official name in English and several other foreign languages from Estonia to Estland (which is the country's name in Danish, Dutch, German, Swedish, Norwegian and many other Germanic languages).[10][11]

Gallery

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Eesti lipp (Estonian Flag)". Riigikantselei (Government Office) (in Estonian). Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "Estonia". fotw.info.

- ↑ "Estonia's History". Estonia's History. December 3, 2013. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ "Estonia's Blue-Black-White Tricolour Flag". Estonian Embassy in Washington. January 1, 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ "Flag of Estonia: History of the Estonian Flag". Estonian Free Press.

- 1 2 3 "Estonian Flag Act". Riigi Teataja. Riigikantselei, Justiitsministeerium. 2014-06-14. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ↑ Tarand, Kaarel (December 3, 2001). "Lippude vahetusel" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ "Estonian Life" (PDF). Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Ilves, Toomas Hendrik (December 14, 1999). "Estonia as a Nordic Country". Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ Kross, Eerik-Niiles (November 12, 2001). "Estland, Estland über alles" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ Representations on the Margins of Europe: Politics and Identities in the Baltic and South Caucasian States, Tsypylma Darieva, Wolfgang Kaschuba Campus, 2007, page 154

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flags of Estonia. |

.svg.png)