Equivalence test

Equivalence tests are a variation of hypothesis tests used to draw statistical inferences from observed data. In equivalence tests, the null hypothesis is defined as an effect large enough to be deemed interesting, specified by an equivalence bound. The alternative hypothesis is any effect that is less extreme than said equivalence bound. The observed data is statistically compared against the equivalence bounds. If the statistical test indicates the observed data is surprising, assuming that true effects as least as extreme as the equivalence bounds, a Neyman-Pearson approach to statistical inferences can be used to reject effect sizes larger than the equivalence bounds with a pre-specified Type 1 error rate.

Equivalence testing originates from the field of pharmacokinetics.[1] One application is to show that a new drug that is cheaper than available alternatives works just as well as an existing drug. In essence, equivalence tests consist of calculating a confidence interval around an observed effect size, and rejecting effects more extreme than the equivalence bound when the confidence interval does not overlap with the equivalence bound. In two-sided tests an upper and lower equivalence bound is specified. In non-inferiority trials, where the goal is to test the hypothesis that a new treatment is not worse than existing treatments, only a lower equivalence bound is pre-specified.

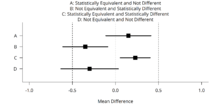

Equivalence tests can be performed in addition to null-hypothesis significance tests.[2] This might prevent common misinterpretations of p-values larger than the alpha level as support for the absence of a true effect. Furthermore, equivalence tests can identify effects that are statistically significant but practically insignificant, whenever effects are statistically different from zero, but also statistically smaller than any effect size deemed worthwhile (see Figure).[3]

TOST procedure

A very simple equivalence testing approach is the ‘two-one-sided t-tests’ (TOST) procedure.[4] In the TOST procedure an upper (ΔU) and lower (–ΔL) equivalence bound is specified based on the smallest effect size of interest (e.g., a positive or negative difference of d = 0.3). Two composite null hypotheses are tested: H01: Δ ≤ –ΔL and H02: Δ ≥ ΔU. When both these one-sided tests can be statistically rejected, we can conclude that –ΔL < Δ < ΔU, or that the observed effect falls within the equivalence bounds and is statistically smaller than any effect deemed worthwhile, and considered practically equivalent.[5] Alternatives to the TOST procedure have been developed as well.[6]

Further reading

- Walker, Esteban; Nowacki, Amy S. (February 2011). "Understanding Equivalence and Noninferiority Testing". Journal of General Internal Medicine. Springer. 26 (2). doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1513-8. PMC 3019319. PMID 20857339.

References

- ↑ Hauck, Walter W.; Anderson, Sharon (1984-02-01). "A new statistical procedure for testing equivalence in two-group comparative bioavailability trials". Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics. 12 (1): 83–91. doi:10.1007/BF01063612. ISSN 0090-466X.

- ↑ Rogers, James L.; Howard, Kenneth I.; Vessey, John T. "Using significance tests to evaluate equivalence between two experimental groups". Psychological Bulletin. 113 (3): 553–565. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.553.

- ↑ Lakens, Daniël (2017-05-05). "Equivalence Tests". Social Psychological and Personality Science. doi:10.1177/1948550617697177.

- ↑ Schuirmann, Donald J. (1987-12-01). "A comparison of the Two One-Sided Tests Procedure and the Power Approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability". Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics. 15 (6): 657–680. doi:10.1007/BF01068419. ISSN 0090-466X.

- ↑ Seaman, Michael A.; Serlin, Ronald C. "Equivalence confidence intervals for two-group comparisons of means". Psychological Methods. 3 (4): 403–411. doi:10.1037/1082-989x.3.4.403.

- ↑ Wellek, Stefan (2010). Testing statistical hypotheses of equivalence and noninferiority. Chapman and Hall/CRC. ISBN 978-1439808184.