Big brown bat

| Big brown bat | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Eptesicus |

| Species: | E. fuscus |

| Binomial name | |

| Eptesicus fuscus (Palisot de Beauvois, 1796) | |

| |

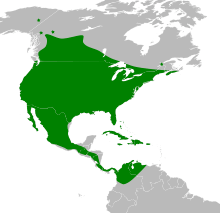

| Range map | |

The big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) is a widespread species of bat found throughout North America, Central America, the Caribbean, and extreme northern South America.

Taxonomy and etymology

The big brown bat was described in 1796 by French naturalist Palisot de Beauvois. Palisot described the species based on specimens in the museum of Charles Willson Peale, an American naturalist.[2] Its species name "fuscus" is Latin in origin, meaning "dark" or "black". To date, twelve subspecies are recognized:[3]

| Subspecies | Authority | Type locality |

|---|---|---|

| E. f. bahamensis[4] | Gerrit Smith Miller | Nassau, Bahamas |

| E. f. bernardinus[5] | Samuel Nicholson Rhoads | San Bernardino, California |

| E. f. dutertreus[6] | Paul Gervais | Cuba |

| E. f. fuscus[2] | Palisot de Beauvois | Philadelphia |

| E. f. hispaniolae[7] | Gerrit Smith Miller | Constanza, Dominican Republic |

| E. f. lynni[8] | Harold H. Shamel | Montego Bay, Jamaica |

| E. f. miradorensis[9] | Joel Asaph Allen | Veracruz, Mexico |

| E. f. osceola[5] | Samuel Nicholson Rhoads | Tarpon Springs, Florida |

| E. f. pallidus[10] | R. T. Young | Boulder, Colorado |

| E. f. peninsulae[11] | Oldfield Thomas | Sierra de la Laguna, Mexico |

| E. f. petersoni[12] | Gilberto Silva Taboada | Isla de la Juventud, Cuba |

| E. f. wetmorei[13] | Hartley H. T. Jackson | Maricao, Puerto Rico |

As the genus Eptesicus is fairly speciose, it is further divided into morphologically similar "species groups". The big brown bat belongs to the serotinus group, which also includes:[14]

- Little black serotine, E. andinus

- Botta's serotine, E. bottae

- Brazilian brown bat, E. brasiliensis

- Diminutive serotine, E. diminutus

- Argentine brown bat, E. furinalis

- Long-tailed house bat, E. hottentotus

- Harmless serotine, E. innoxius

- Meridional serotine, E. isabellinus

- Lagos serotine, E. platyops

- Serotine bat, E. serotinus

- Sombre bat, E. tatei

The serotinus group is defined by having a large, elongate skull, flat braincase, and a long snout.[14] The big brown bat is most closely related to other American species of its genus—the diminutive serotine, Brazilian brown bat, and the Argentine brown bat.[15]

Description

It is a relatively large microbat, weighing 15–26 g (0.53–0.92 oz). Adult body length is 110–130 mm (4.3–5.1 in).[16] Its forearm is usually longer than 48 mm (1.9 in).[17] Its wingspan is 32.5–35 cm (12.8–13.8 in). Its dorsal fur is reddish brown and glossy in appearance; ventral fur is lighter brown. Its snout, uropatagium, and wing membranes are black and hairless. Its ears are also black;[16] they are relatively short with rounded tips.[17] The tragi also have rounded tips.[16] Its dental formula is 2.1.1.33.1.2.3, for a total of 32 teeth.[18]

One study of a population in Colorado found that their average life expectancy was a little over 6.5 years;[19] the oldest known big brown bat was 19 years of age and documented in Canada.[20]

Biology

Diet

Big brown bats are insectivorous, eating many kinds of insects including beetles, flies, stone flies, mayflies, true bugs, net-winged insects, scorpionflies, caddisflies, and cockroaches.[18] It will forage in cities around street lamps. As the big brown bat is such a widespread species, it has regional variation in its diet, though it is generally considered a beetle specialist that rarely eats moths, though some populations do not follow this trend. Populations in Indiana and Illinois have particularly high consumption of scarab beetles, cucumber beetles, ground beetles and shield bugs. In Oregon, primary prey items include moths in addition to scarab beetles and ground beetles. In British Columbia, large proportions of caddisflies are consumed, with flies as a secondary prey source.[21] Big brown bats are significant predators of agricultural pests. A 1995 study found that a colony of 150 big brown bats consumes 600,000 cucumber beetles, 194,000 scarab beetles, 158,000 leafhoppers, and 335,000 stink bugs per year, all of which cause serious agricultural damage.[22]

Behavior

The big brown bat is nocturnal, roosting in sheltered places during the day. It will utilize a wide variety of structures for roosts, including mines, caves, tunnels, buildings, bat boxes, tree cavities, storm drains, wood piles, and rock crevices.[21] They generally roost in cavities, though they can sometimes be found under exfoliating bark. In 1995, Kurta published that he had observed a strip of bark peel away from a tree and fall into water below, with a torpid big brown bat still attached to the bark, per Kunz 2005.[23][24] Both solitary males and solitary, non-pregnant/non-lactating females have been found roosting under bark.[25]

Hibernation

.jpg)

Big brown bats hibernate during the winter months, often in different locations from their summer roosts. Winter roosts tend to be natural subterranean locations such as caves and underground mines where temperatures remain stable; where a large majority of these bats spend the winter is still unknown. If the weather warms enough, they may awaken to seek water, and even breed.

Reproduction

Big brown bat mating season is in the fall. After the breeding season, pregnant females separate into maternity colonies.[18] Historically, maternity colonies were probably in tree cavities. In modern, human-dominated landscapes, however, many maternity colonies are in buildings.[21] In the eastern United States, twins are commonly born sometime in June; in western North America, females give birth to only one pup each year. A dissected female was once found with four embryos; had the female given birth, though, it is unlikely that all four would have survived.[18] Like most species of bat,[26] the big brown bat only has two nipples. At birth, pups are only 3 g (0.11 oz), though they grow quickly, gaining up to 0.5g per day.[18]

Diseases

Like all bats in the United States,[27] big brown bats can be affected by rabies, which can be a concern for public health as they commonly roost in buildings, and thus have a higher chance of encountering humans. The incubation period for rabies in this species can exceed four weeks,[28] though the mean incubation period is 24 days.[27] Rabid big brown bats will bite each other, which is the primary method of transmission from individual to individual. However, not all individuals will develop rabies after exposure to the virus. Some individuals have been observed with a sufficiently high rabies antibody concentration to confer immunity. Rabies immunity can be passed from mother to pup via passive immunity or from exposure to the bite of a rabid individual. Overall, a low proportion of big brown bats become infected with rabies. Populations of big brown bats in the Eastern United States have a different strain of rabies than the populations in the Western United States.[28] In one study, only 10% of big brown bats were shedding the rabies virus through their saliva before exhibiting clinical symptoms of the disease; symptoms of rabies in big brown bats include acute weight loss, paralysis, ataxia, paresis, and unusual vocalizations.[27]

Range and habitat

The big brown bat is encountered widely throughout North America. It has been called "the most widespread Pleistocene bat in North America".[17] It is found from southern Canada and Alaska to as far south as Colombia and Venezuela. It has also been documented in the Caribbean in both the Greater and Lesser Antilles, including Hispaniola, Dominica, Barbados, and the Bahamas. The big brown bat has been documented from 300–3,100 m (980–10,170 ft) above sea level.[1] It is a generalist, capable of living in urban, suburban, or rural environments.[21]

Conservation

The big brown bat is evaluated at the lowest conservation priority by the IUCN—least concern. It meets the criteria for this designation because it has a wide geographic distribution, a large population size, occurrence in protected areas, and tolerance to habitat modification by humans.[1] While other bat species in the Eastern United States have experienced significant population declines (up to 98% loss) due to white-nose syndrome, the big brown bat is relatively resistant to its effects. Even in caves infected by Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome, big brown bats maintain normal torpor patterns. Unlike in other species more affected by white-nose syndrome, big brown bats are able to retain more of their body fat throughout hibernation. In fact, some regions of the Eastern U. S. have seen an increase in big brown bat populations since the arrival of white-nose syndrome.[29]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Miller, B.; Reid, F.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Cuarón, A.D.; de Grammont, P.C. (2016). "Eptesicus fuscus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T7928A22118197. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- 1 2 Palisot de Beauvois, A. M. F. J. (1796). A scientific and descriptive catalogue of Peale's museum. Philadelphia: SH Smith. p. 18.

- ↑ "Eptesicus fuscus". ITIS.gov. Integrated Taxonomic Information System on-line database. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ↑ Miller Jr, G. S. (1897). North American Fauna: Revision of the North American bats of the family Vespertilionidae. U.S. Department of Agriculture. pp. 101–102.

- 1 2 Rhoads, S. N. (1901). "On the common brown bats of peninsular Florida and southern California". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia: 618–619.

- ↑ Gervais, P. (1837). "Sur les animaux mamifères des Antilles". L'Institut, Paris. 5 (218): 253–254.

- ↑ Miller, G. S. (1918). "Three new bats from Haiti and Santo Domingo". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 31: 39–40.

- ↑ Shamel, H. H. (1945). "A new Eptesicus from Jamaica". Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington. 58: 107–110.

- ↑ Allen, H. (1866). "Notes on the Vespertilionidae of tropical America". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia: 287–288.

- ↑ Young, R. T. (1908). "Notes on the distribution of Colorado mammals, with a description of a new species of bat (Eptesicus pallidus) from Boulder". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia: 403–409. JSTOR 4063298.

- ↑ Thomas, O. (1898). "VII.–On new mammals from Western Mexico and Lower California". Journal of Natural History. 1 (1): 43–44. doi:10.1080/00222939808677921.

- ↑ Silva-Taboada, G. (1974). "Fossil Chiroptera from cave deposits in central Cuba, with description of two new species (genera Pteronotus and Mormoops) and the first West Indian record of Mormoops megalophylla". Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia. 19.

- ↑ Jackson, H. H. T. "A new bat from Porto Rico". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 29: 37–38.

- 1 2 Hill, J. E.; Harrison, D. L. (1987). The baculum in the Vespertilioninae (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) with a systematic review, a synopsis of Pipistrellus and Eptesicus, and the descriptions of a new genus and subgenus. London: Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Zoology. pp. 251–253.

- ↑ Juste, J.; Benda, P.; Garcia‐Mudarra, J. L.; Ibanez, C. (2013). "Phylogeny and systematics of Old World serotine bats (genus Eptesicus, Vespertilionidae, Chiroptera): an integrative approach" (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 42 (5): 441–457. doi:10.1111/zsc.12020.

- 1 2 3 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (2013). Wisconsin Big Brown Bat Species Guidance (PDF) (Report). Bureau of Natural Heritage Conservation, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. PUB-ER-707. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- 1 2 3 Kurta, A.; Baker, R. H. (1990). "Eptesicus fuscus". Mammalian Species (356): 1–10. doi:10.2307/3504258.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davis, W.B. (1994). "Big Brown Bat". The Mammals of Texas - Online Edition. Texas Tech University. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ↑ O'shea, T. J.; Ellison, L. E.; Stanley, T. R. (2011). "Adult survival and population growth rate in Colorado big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus)". Journal of Mammalogy. 92 (2): 433–443. doi:10.1644/10-mamm-a-162.1.

- ↑ Hitchcock, H. B. (1965). "Twenty-three years of bat banding in Ontario and Quebec". Canadian Field-Naturalist (79): 4–14.

- 1 2 3 4 Agosta, S. J. (2002). "Habitat use, diet and roost selection by the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) in North America: a case for conserving an abundant species" (PDF). Mammal Review. 32 (3): 179–198. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.2002.00103.x.

- ↑ Whitaker Jr, J. O. (1995). "Food of the big brown bat Eptesicus fuscus from maternity colonies in Indiana and Illinois". American Midland Naturalist. 134: 346–360. doi:10.2307/2426304. JSTOR 2426304.

- ↑ Kurta, Allen (1995). Mammals of the great lakes region. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472094971.

- ↑ Kunz, T. H.; Fenton, M. B., eds. (2005). Bat ecology. University of Chicago Press. p. 18. ISBN 0226462072.

- ↑ Christy, R.E.; West, S.D. (1993). Biology of bats in douglas-fir forests (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Agriculture. p. 10. PNW-GTR-308. Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- ↑ Simmons, N. B. (1993). "Morphology, function, and phylogenetic significance of pubic nipples in bats (Mammalia, Chiroptera)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3077).

- 1 2 3 Jackson, F. R.; Turmelle, A. S.; Farino, D. M.; Franka, R.; McCracken, G. F.; Rupprecht, C. E. (2008). "Experimental rabies virus infection of big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus)". Journal of wildlife diseases. 44 (3): 612–621. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-44.3.612.

- 1 2 Shankar, V.; Bowen, R. A.; Davis, A. D.; Rupprecht, C. E.; O'Shea, T. J. (2004). "Rabies in a captive colony of big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus)". Journal of wildlife diseases. 40 (3): 403–413. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-40.3.403.

- ↑ Frank, C. L.; Michalski, A.; McDonough, A. A.; Rahimian, M.; Rudd, R. J.; Herzog, C. (2014). "The resistance of a North American bat species (Eptesicus fuscus) to white-nose syndrome (WNS)". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e113958. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113958.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eptesicus fuscus. |

| Bat Chirp | |

|

|

- Eptesicus fuscus Echolocation Lab at Brown University

- NewScientist.com Article from issue 2581 of New Scientist magazine, 6 December 2006, page 21- Claims bats can navigate by sensing Earth's magnetic field

- Identifying Big Brown Bats by Professional Humane Bat Removers in New England

- Video of Big Brown Bat from Boulder, CO