Enkidu

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

Seven gods who decree

|

|

Other major deities |

|

Demigods and heroes

|

| Related topics |

Enkidu (𒂗𒆠𒆕 EN.KI.DU3, "Enki's creation"), formerly misread as Eabani, is a central figure in the Ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh. Enkidu was formed from clay and water by Aruru, the goddess of creation, to rid Gilgamesh of his arrogance.

In the story he is a wild man, raised by animals and ignorant of human society until he is bedded by Shamhat. Thereafter a series of interactions with humans and human ways bring him closer to civilization, culminating in a wrestling match with Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. Enkidu embodies the wild or natural world. Though equal to Gilgamesh in strength and bearing, he acts in some ways as an antithesis to the cultured, urban-bred warrior-king. Enkidu then becomes the king's constant companion and deeply beloved friend, accompanying him on adventures until he is stricken with illness and dies.

The deep, tragic loss of Enkidu profoundly inspires in Gilgamesh a quest to escape death by obtaining godly immortality.[1]

Creation of Enkidu

The people of Uruk complain to the gods that their mighty king Gilgamesh is too harsh. The goddess Aruru forms Enkidu from water and clay as rival to Gilgamesh, as a countervailing force. Enkidu lived in the wild, roaming with the herds, and joining the game at the watering-hole. M.H. Henze notes in this an early Mesopotamian tradition of the wild man living apart and roaming the hinterland, who eats grass like the animals and like them, drinks from the watering places.[2]

A hunter sees him and realizes that it is Enkidu who is freeing the animals from his traps. He reports this to Gilgamesh, who sends the temple prostitute, Shamhat, to deal with him.[3]

Enkidu spends six days and seven nights copulating with Shamhat, after which, sensing her scent upon him, the animals flee from him, and he finds he cannot return to his old ways.[4] He returns to Shamhat, who teaches him the ways of civilized people. He now protects the shepherd's flock against predators, turning against his old life. Jastrow and Clay are of the opinion that the story of Enkidu was originally a separate tale to illustrate "man's career and destiny, how through intercourse with a woman he awakens to the sense of human dignity, ..."[5]

Shamhat tells him of the city of Uruk and of its king Gilgamesh. He travels to Uruk and engages Gilgamesh in a wrestling match as a test of strength. Gilgamesh wins and the two become fast friends.

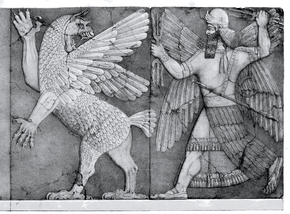

Adventures with Gilgamesh

Enkidu assists Gilgamesh in defeating and killing Humbaba, the guardian monster of the Cedar Forest. Enkidu selects a particularly tall tree to provide lumber for a new door for Enlil's temple in Uruk. Later, he assists Gilgamesh in slaying Gugalanna the Bull of Heaven, which the gods have sent to kill Gilgamesh as a reprisal for rejecting Ishtar's affections while enumerating the misfortunes that befell her former lovers. Ishtar demands that the pair pay for the bull's destruction. Shamash appeals to the other gods to let both of them live, but only Gilgamesh is spared. Enkidu succumbs to a wasting illness. He represents the hero who wins fame but dies early.[6] Gilgamesh responds to the loss of Enkidu by seeking out Utnapishtim in a quest for eternal life.

There is another non-canonical tablet in which Enkidu journeys into the underworld, but many scholars consider the tablet to be a sequel or add-on to the original epic as the work was revised several times. The section about the Flood is also considered to be addition.[7]

Some modern individuals interpret the depiction of Gilgamesh and Enkidu's relationship as erotic.[8][9]

See also

Notes

- ↑

- ↑ Henze, M.H. (1999). The Madness of King Nebuchadnezzar. Brill. ISBN 9789004114210 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "The Coming of Enkidu". The Epic of Gilgamesh. Assyrian International News Agency.

- ↑ Westenholz, Aage; Koch-Westenholz, Ula (2000). "Enkidu - the noble savage?". In Lambert, Wilfred G.; George, A. R.; Finkel, Irving L. Wisdom, Gods, and Literature: Studies in Assyriology in Honour of W.G. Lambert. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060040 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Jastrow, Morris Jr.; Clay, ALbert T. (1920). An Old Babylonian Version of the Gilgamesh Epic. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 20 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Wolff, H. N. (April–June 1969). "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the heroic life". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 89 (2): 392–398.

- ↑ Moran, William L. (1991). Epic of Gilgamesh: A document of ancient humanism. The Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies Bulletin. p. 20. ISSN 0844-3416. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ Ackerman, Susan (2005). When Heroes Love. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231507257. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ Sadownick, Douglas; Walker, Mitch (7 April 2012). The Romance of Gilgamesh. YouTube (online video). Retrieved 27 March 2015.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Enkidu. |

- Foster, Benjamin R., ed. (2001). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Translated by Foster, Benjamin R. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97516-9.

External links

- "Enkidu sitting astride Gugalanna, the Bull of Heaven".

- Bertman, Stephen (14 July 2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)