Emilia Plater

| Countess Emilia Plater | |

|---|---|

|

Emilia Plater, anonymous 19th century engraving | |

| Born |

13 November 1806 Vilnius, Russian Empire |

| Died |

23 December 1831 (aged 25) Justianowo, Congress Poland |

| Buried | Kapčiamiestis |

| Allegiance | Poland (November Uprising insurgents) |

| Years of service | 1830 |

| Rank | captain |

| Battles/wars | November Uprising |

Countess Emilia Plater (Broel-Plater, Lithuanian: Emilija Pliaterytė; 13 November 1806 – 23 December 1831) was a noblewoman and revolutionary[1] from the lands of the partitioned Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[2][3][4] Raised in a patriotic tradition, she fought in the November 1830 Uprising, during which she raised a small unit, participated in several engagements, and received the rank of captain in the Polish insurgent forces. Near the end of the Uprising, she fell ill and died.

Though she did not participate in any major engagement, her story became widely publicized and inspired a number of works of art and literature. She is a national heroine in Poland and Lithuania, all formerly parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. She has been venerated by Polish artists and by the nation at large as a symbol of women fighting for the national cause. She is often nicknamed as a "Lithuanian Joan of Arc".[5]

Biography

Early life

Emilia Plater was born in Vilnius into a noble Polish–Lithuanian Plater family.[6] Her family, of the Plater coat of arms,[6] traced its roots to Westphalia, but was thoroughly Polonized.[7] Much of the family relocated to Livonia during the 15th century and later to Lithuania, of which Vilnius is the capital.[6] She is described as either Polish, Polish-Lithuanian or Lithuanian.[8][9][10][11]

Her parents, Franciszek Ksawery Plater and Anna von der Mohl (Anna z Mohlów), divorced when she was nine years old, in 1815.[12] She was brought up by distant relatives, Michał Plater-Zyberk and Izabela Helena Syberg zu Wischling, in their family's manor Līksna near Daugavpils (Dźwina), then Inflanty (now Latvia).[12] Well-educated, Plater was brought up to appreciate the efforts of Tadeusz Kościuszko and the Prince Józef Poniatowski.[13] She was fascinated by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller, who she could read in the original German language. She was raised in an environment that valued the history of Poland, and her literary heroes included Princess Wanda and Adam Mickiewicz's Grażyna.[12] She also admired Bouboulina, a woman who became one of the icons of the Greek uprising against the Ottomans,[12] a Polish fighter Anna Dorota Chrzanowska,[12] as well as Joan of Arc.[13] These pursuits were accompanied by an early interest in equestrianism and marksmanship, quite uncommon for early 19th-century girls from aristocratic families.[12] She was also deeply interested in Ruthenian and Belarusian folk culture.[12] She had contacts and friends in the Filaret Association.[12]

In 1823, one of her cousins was forcibly conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army as a punishment for celebrating the Constitution of 3 May; this incident is said to be one of the key events in her life, and one that galvanized her pro-Polish and anti-Russian attitude.[7] In 1829, Plater began a grand tour throughout the historical Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, visiting Warsaw and Kraków, and the battlefield of Raszyn. Her mother died a year later; her father remarried and refused to even meet his daughter.[12] After the outbreak of the November Uprising against Imperial Russia, she became a vocal supporter of the anti-Tsarist sentiments in the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[12] She became one of a dozen or so females to join the Uprising, and the most famous of them all.[12]

Uprising

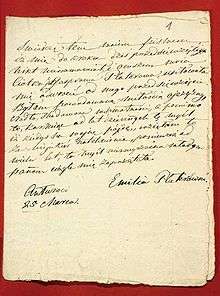

A document from 25 March contains her note that joining the uprising was her sole idea, and that she had hoped that such a moment would come her entire life.[12] She cut her hair, prepared a uniform for herself and organized and equipped a group of volunteers, speaking passionately after a mass on 29 March.[12] On 4 April she signed a declaratory document marking her access to the local uprising forces.[12] Her unit was composed of roughly 280 infantry, 60 cavalry and several hundred peasants armed with war scythes.[14]

From the area of Daugavpils she entered Lithuania, where in April 1831 her unit is rumored to have seized the town of Zarasai, although the historians are not sure this event really occurred.[12] She planned to take Daugavpils, but after a reconnaissance mission discovered that the city was defended by a strong garrison and was impregnable to attack by such a small force as her own unit, that plan was abandoned.[12] She then returned to Samogitia and headed for Panevėžys, where on 30 April she joined forces with the unit commanded by Karol Załuski.[12] On May 4, she fought at the battle of Prastavoniai; shortly afterwards, with Konstanty Parczewski, she fought at Maišiagala.[12] On 5 May, she witnessed General Dezydery Chłapowski entering the area with a large force and taking command over all units fighting in the former Grand Duchy.[12]

Chłapowski advised Plater to stand down and return home. She allegedly replied that she had no intention of taking off her uniform until her fatherland was fully liberated. Her decision was accepted and she was made a commanding officer of the 1st company of the Polish–Lithuanian 25th Infantry Regiment.[12] She was promoted to the rank of captain,[7] the highest rank awarded to a woman at that time. She spent some time in Kaunas, before the insurgents were forced to retreat in late June.[12]

After the Polish units were defeated by the Russians at Šiauliai, Gen. Chłapowski decided to cross the border into Prussia and become interned there.[12] Plater vocally criticized that decision, refused to follow orders and instead decided to try to break through to Warsaw and continue the struggle.[12] However, soon after separating from the main force, accompanied by only two others, including her cousin (or uncle, sources vary), Cezary Plater, she became seriously ill.[12] She never recovered, and she died in a manor of the Abłamowicz family in Justinavas on 23 December 1831.[12] She was buried in the small village of Kapčiamiestis near Lazdijai.[15] After the defeat of the uprising, her estate was confiscated by the Russian authorities.[15]

Stefan Kieniewicz, in a more critical treatment in the Polish Biographical Dictionary, notes that a lot of her exploits are poorly documented, and it is not always possible to separate legend from facts.[12] He notes it is not certain she ever commanded any unit, and that her role as the commander of the 25th Regiment was more honorary than real; he also notes that she is known to have fainted on the battlefield, distracting her comrades, and in at least one instance (at the battle of Šiauliai), she was purposefully held behind front lines, as her comrades tried to ensure she would not endanger herself.[12]

Legacy

Her death was widely publicised shortly afterwards by the Polish press, which contributed to her growing fame.[15] Plater became one of the symbols of the uprising. The symbol of the fighting girl became quite widespread both in Poland, Lithuania and abroad. Mickiewicz immortalized her in his poem, Śmierć pułkownika (Death of a Colonel), although the description of her death is a pure poetical fiction and was only loosely based on her real life.[13][15] Mickiewicz has also idealized her personality and skills, portraying her as the ideal commander, worshiped by her soldiers.[15] That poem has entered the elementary curriculum in the independent Poland.[13]

Other literary works based on her life were published, mostly abroad, both by Polish emigres and by foreigners.[15] Among them were Georg Büchner, Konstanty Gaszyński,[15] Wacław Gąsiorowski,[15] Tadeusz Korczyński,[15] Antoni Edward Odyniec[15] and Władysław Buchner. Józef Straszewicz published three successive versions of her biography in French.[15]

She also became the theme of paintings by several artists of the epoch, among them Hyppolyte Bellange, Achille Deveria,[15] Philipp Veit, Francois de Villain and Wojciech Kossak.[15] In 1842, J. K. Salomoński published a short biography of Plater in New York, under the title of Emily Plater, The Polish Heroine; Life of the Countess Emily Plater. A lithograph by F. De Villaine, based on Deveria's work, became one of the most recognizable portraits of her, popularizing her image as a delicate and noble female warrior.[15]

She was depicted on the Second Polish Republic's 20 złoty note.[15] During World War II, a Polish female support unit, Emilia Plater 1st Independent Women's Battalion (1 Samodzielny Battalion Kobiecy im. Emilii Plater), a part of the Soviet Polish 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Infantry Division was named in her honor;[15] its former members founded a village of Platerówka in Lower Silesia.[16] Several streets in Poland are named after her, including one in Warsaw.[15] In 1959, the MS Emilia Plater, a Polish Merchant Navy bulk carrier, was named after her.[17]

Her life has also been a subject to studies from a feminist perspective, by scholars to point out the significance of her participation in the military conflict as a female going against the stereotype that only males can fight.[18]

References

- ↑ Robin Morgan (1 November 1996). Sisterhood is Global: The International Women's Movement Anthology. Feminist Press. p. 559. ISBN 978-1-55861-160-3. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ "Litwa: przewodnik", Tomasz Krzywicki, Oficyna Wydawnicza "Rewasz", 2005, s. 196

- ↑ W pamięci potomnych

- ↑ Shastouski, K. "Grób Emilii Broel-Plater - wieś Kopciowo okręg olicki". Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ Plikūnė, Dalia. "Lietuviškoji Žana d'Ark – grafaitė, atsisakiusi tekėti už caro generolo ir pasirinkusi visai kitą gyvenimo kelią". DELFI.lt. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 Heart of Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-19-164713-0. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Ethnologia Europaea, Vol.21-22, 1991 p.132

- ↑ Szymon Konarski (1967). Materiały do biografii: genealogii i heraldyki polskiej. Paris. p. 215.

- ↑ Mary Fleming Zirin (2007). Russia, the non-Russian peoples of the Russian Federation, and the successor states of the Soviet Union. M.E. Sharpe. p. 695. ISBN 978-0-7656-0737-9. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ Suzanne LaFont (August 1998). Women in transition: voices from Lithuania. SUNY Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7914-3811-4. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Stefan Kieniewicz, Emilia Plater, Polski Słownik Biograficzny, Tom XXVII, Zakład Narodowy Imenia Ossolińskich I Wydawnictwo Polskieh Akademii Nauk, 1983, p.652

- 1 2 3 4 Ellen Berry (1 July 1995). Genders 22: Postcommunism and the Body Politic. NYU Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8147-1248-1. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ Dioniza Wawrzykowska-Wierciochowa (1982). Sercem i orężem Ojczyźnie służyły: Emilia Plater i inne uczestniczki powstania listopadowego, 1830-1831. MON. p. 180. ISBN 978-83-11-06734-9. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Stefan Kieniewicz, Emilia Plater, Polski Słownik Biograficzny, Tom XXVII, Zakład Narodowy Imenia Ossolińskich I Wydawnictwo Polskieh Akademii Nauk, 1983, p.653

- ↑ Bernard A. Cook (1 May 2006). Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 476. ISBN 978-1-85109-770-8. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Morski rocznik statystyczny. Wydawn. Morskie. 1960. p. 173. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ↑ Pamela Chester; Sibelan Elizabeth S. Forrester; Halina Filipowicz (1996). "The Daughters of Emilia Plater'". Engendering Slavic Literatures. Indiana University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-253-33016-1. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emilia Plater. |

- Original letter by Emilia Plater, in which she confirms the fact that she joined the ranks of the army of her own will

- Westphalian Plater family

- Death place of Emilia Plater. Ruins of Justinavas manor and Emilia's sculpture