Elmer E. Ellsworth

| Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth | |

|---|---|

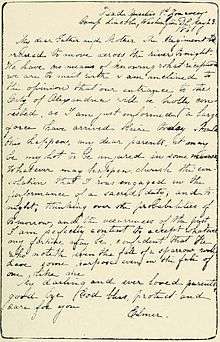

Col. Elmer Ellsworth in 1861 | |

| Born |

April 11, 1837 Malta, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

May 24, 1861 (aged 24) Alexandria, Virginia, U.S. |

| Buried |

Hudson View Cemetery Mechanicville, New York, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1861 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth (April 11, 1837 – May 24, 1861) was a law clerk and United States Army soldier, best known as the first conspicuous casualty[1] and the first Union officer to die[2] in the American Civil War.[3] He was killed while removing a Confederate flag from the roof of the Marshall House Inn of Alexandria, Virginia, at the behest of Abraham Lincoln, as the flag had been visible from the White House as a defiant sign of the Confederacy.[1]

Prior to the war, Ellsworth was the leader of a touring military drill team known as the "Fire Zouaves" and a close personal friend of Lincoln, who later eulogized him "the greatest little man I ever met". After his death, Ellsworth's body lay in state at the White House. The phrase, "Remember Ellsworth", became a rallying cry and tool for recruiting Union soldiers.

Early life

Born as Ephraim Elmer Ellsworth[4] in Malta, New York, Ellsworth grew up in Mechanicville, New York, and later relocated to New York City. In 1854, he moved to Rockford, Illinois, where he worked for a patent agency. In 1859, he became engaged to Carrie Spafford, the daughter of a local industrialist and city leader. When Carrie's father demanded that he find more suitable employment, he moved to Chicago to study law and work as a law clerk.

In 1860, Ellsworth relocated to Springfield, Illinois to work with Abraham Lincoln. Studying law under Lincoln, he also helped with Lincoln's 1860 campaign for president, and accompanied Lincoln to Washington, D.C. following his election. Ellsworth was only 5 ft 6 in (168 cm) tall, but Lincoln called him "the greatest little man I ever met".[1]

Military career

In 1857, Ellsworth became drillmaster of the "Rockford Greys", the local militia company. He also studied military science in his spare time. After some success with the Greys, he helped train militia units in Milwaukee and Madison. When he moved to Chicago, he became Colonel of Chicago's National Guard Cadets.

Ellsworth had studied the Zouave soldiers, French colonial troops in Algeria, and was impressed by their reported fighting quality. He outfitted his men in Zouave-style uniforms, and modeled their drill and training on the Zouaves. Ellsworth's unit became a nationally famous drill team.[5]

Following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate Army troops in mid-April 1861, and Lincoln's subsequent call for 75,000 volunteers to defend the nation's capital, Ellsworth raised the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment (the "Fire Zouaves") from New York City's volunteer firefighting companies, and was then commissioned as the regiment's commanding officer.

Death

Ellsworth had, on occasion, joined the Lincolns in "peering curiously across the river at [a] large rebel banner that had mocked them for a month from the skyline of Alexandria," or roughly, since the first casualties of the Civil War occurred on April 19, 1861, in the Baltimore riot.[1] "For some anxious Unionists, that flag was becoming a symbol of the administration's slowness to move against the gathering forces of the Confederacy."[6] This was not the later-designed, more famous "Battle flag", but rather the official "Stars and Bars" flag that more closely resembles the Union flag. On May 23, 1861, Virginia's secession was ratified by referendum.

The following day, Ellsworth led the 11th New York across the Potomac and into the streets of Alexandria in the wake of and uncontested by a retreating Confederate army. He detached some men to take the railroad station while he led others to secure the telegraph office. On his way there, Ellsworth turned a corner and came face to face with the Marshall House Inn, atop of which the banner was still flying. He ordered a company of infantry as reinforcements and continued on his way to the telegraph office. But suddenly, Ellsworth changed his mind, turned around, and went up the steps of the Marshall House.

He entered the house accompanied by seven men. Once inside, they found a "disheveled-looking man, only half dressed, who had apparently just gotten out of bed" and who informed them that he was a boarder, upon Ellsworth's demand to know what the Confederate flag was doing atop the hotel.[7] Ellsworth and four men then went upstairs to cut down the flag. As Ellsworth came downstairs with the (very large) flag, the sleepy "boarder" who was actually the owner of the house and one of the most ardent of secessionists in Alexandria, James W. Jackson, killed Ellsworth with a shotgun blast to the chest. Corporal Francis E. Brownell, of Troy, New York, immediately killed Jackson, either by shooting him[2] or stabbing him with the bayonet on the end of his gun.[8] Brownell was later awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions.[2]

Lincoln was deeply saddened by his friend's death and ordered an honor guard to bring his friend's body to the White House, where he lay in state in the East Room.[1][9][10][11] Ellsworth's body was then taken to the City Hall in New York City, where thousands of Union supporters came to see the first man to fall for the Union cause. Ellsworth was then buried in his hometown of Mechanicville, in the Hudson View Cemetery.

Thousands of Union supporters rallied around Ellsworth's cause and enlisted. "Remember Ellsworth" was a patriotic slogan: the 44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment called itself the "Ellsworth Avengers", as well as "The People's Ellsworth Regiment."

Legacy

Relics associated with Ellsworth's death became prized souvenirs. The Smithsonian Institution and Bates College's Special Collections Library have pieces of the Confederate flag that Ellsworth had when he was shot—in 1894, Brownell's widow was offering to sell small pieces of the flag for $10 and $15 each. The New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center in Saratoga Springs has most of the flag itself and Ellsworth's uniform, showing the hole from the fatal shot. The Fort Ward Museum in Alexandria dedicates a section of their museum to Ellsworth, displaying the kepi he wore when he was killed, patriotic envelopes bearing his image, a piece of the Confederate Flag (on which Ellsworth's blood is still visible), and the "O" from the Marshall House sign that a soldier took as a souvenir.

In 1862, the newly established county seat of Pierce County, Wisconsin, located in the undeveloped center of the county to settle the controversy between two established cities, was named Ellsworth, Wisconsin in his honor.

The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia had a major exhibit devoted to Col. Ellsworth.

In addition, Ellsworth, Michigan, Ellsworth, Wisconsin, Fort Ellsworth, and possibly Ellsworth, Iowa were named in his honor, as were Fort Ellsworth, various other institutions, and various individual people.

In popular culture

- He is a character in the 2012 film Saving Lincoln, in which his death is portrayed.

Selected works

- Ellsworth, Elmer E. (1861). Complete instructions for the recruit in the light infantry drill: as adapted to the use of the rifled musket, and arranged for the United States Zouave cadets. Cornell University Library. p. 76 pages. ISBN 1-4297-1185-X.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Elmer Ellsworth". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- 1 2 3 Edwards, Owen (April 2011). "The Death of Colonel Ellsworth". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- ↑ Hawthorne, Frederick W. "Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments", The Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, Hanover PA 1988 p. 54 & 55

- ↑ "Notable Visitors: Elmer Ellsworth". Mr. Lincoln's White House. Lehrman Institute. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- ↑ Giaimo, Cara (March 29, 2016). "The Civil War Fighters Who Tempted Fate With North African Fashion". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- ↑ Goodheart, p. 280

- ↑ Goodheart, p. 285

- ↑ Davis, p. 64.

- ↑ Goodheart, pp. 288–289

- ↑ Fragment of Confederate flag cut down by Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, 1861, Smithsonian Institution web site (accessed July 2013).

- ↑ Schano, N., Let's Learn from the Past: Col. Elmer Ellsworth", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 26, 2012

References

- Davis, William C., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. First Blood: Fort Sumter to Bull Run. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1983. ISBN 0-8094-4704-5.

- Randall, Ruth Painter (1960). Colonel Elmer Ellsworth: A biography of Lincoln's friend and first hero of the Civil War. Boston: Little Brown.

- Bio of Ellsworth

- Carlson, Sarah-Eva E. (1996). "Preparing for War: Ellsworth, the Militias, and the Zouaves". Illinois History. Springfield, Illiinois: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency (February 1996): 32–34. ISSN 0019-2058. Retrieved 18 Nov 2010.

- Goodheart, Adam (2011-04-05). 1861: The Civil War Awakening. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 0-3075-9666-4.

External links

- Ellsworth's hometown and place of burial, Mechanicville, NY

- Elmer E. Ellsworth at Find a Grave

- Smithsonian's piece of the Ellsworth flag (picture)

- Smithsonian collection - shotgun used to kill Ellsworth (picture)

- Elmer Ellsworth, Citizen Soldier

- New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center

- Sensational Civil War Death Explored in 3 Exhibits

- Envelope Cachet - Our Cause is Just. Fight on Remember Ellsworth.