Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme Elmy

Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme Elmy (1833–1918) was a British feminist women's suffragist campaigner, essayist and poet, who also wrote under the pseudonyms E and Ignota.

Early life

Elizabeth Wolstenholme was born in Cheetham Hill, Manchester and baptised on 15 December 1833 in Eccles, Lancashire where her father was a Methodist minister.[1] She was the daughter of Reverend Joseph Wolstenholme who died around 1843 much of her formative years were spent in Roe Green with her maternal family. Her mother Elizabeth had died when she was very young and she was brought up by her stepmother Mary (née Lord).[2] She attended Fulneck Moravian School for two years but was not permitted to study further. Her brother Joseph Wolstenholme (1829–1891) became a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University. She opened a private girls' boarding school in Boothstown near Worsley and stayed there until May 1867 when she moved her establishment to Congleton in Cheshire.

Campaigning

Wolstenholme, dismayed with the woeful standard of elementary education for girls, joined the College of Preceptors[3] in 1862 and through this organisation met Emily Davies. They campaigned together for girls to be given the same access to higher education as boys. Wolstenholme founded the Manchester Schoolmistresses Association in 1865[4] and in 1866 gave evidence to the Taunton Commission into education, one of the first women to give evidence at a Parliamentary Select Committee. In 1867 Wolstenholme represented Manchester on the newly formed North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women. Emily Davies and Wolstenholme quarrelled over how women should be examined at a Higher Level[5] and Wolstenholme who had formed the Manchester branch of the 'Society for the Promotion of the Employment in Women' in 1865[6] was keen for a curriculum aimed at developing skills for employment whereas Davies wished for women to be taught the same syllabus as men.

Wolstenholme founded the Manchester Committee for the Enfranchisement of Women (MCEW) in 1866[7] and became a vigorous campaigner for women's suffrage for more than 50 years. She gave up her school in 1871 and became the first paid employee of the women's movement when she was paid to lobby Parliament with regard to laws that were injurious to women.[8] Nicknamed 'the Scourge of the Commons' or the 'Government Watchdog' Wolstenholme took her role seriously. When local women's suffragist groups faltered following the disappointment of failed Suffrage Bills, Wolstenholme was instrumental in maintaining the Manchester committee's momentum with a re-grouping in 1867 under the name Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage.

In 1877 the women's suffrage campaign was centralised as the National Society for Women's Suffrage. Wolstenholme was a founding member (with Harriet McIlquham and Alice Cliff Scatcherd) of the Women's Franchise League in 1889.[9][10] Wolstenholme left the organisation and founded the Women's Emancipation Union in 1891[11] but it folded once its benefactor died.

Wolstenholme, a friend and colleague of Emmeline Pankhurst, was invited onto the executive committee of the WSPU[12] and wrote an eye witness account of the 1906 Boggart Clough Hole and White Sunday Hyde Park demonstrations where she was honoured with her own stand. Wolstenholme resigned from the WSPU in 1913 when its violent activities threatened human life. Wolstenholme became vice-president of the Tax Resistant League in the same year and gave her support to the Lancashire and Cheshire Textile and other Workers' Representation Committee formed in Manchester during 1903 headed by Esther Roper.[13]

Wolstenholme was not a single issue campaigner and wanted parity between the sexes. She became secretary to the Married Women's Property Committee from 1867 until 1882 when the organisation was disbanded after its successful campaign to introduce the Married Women's Property Act 1882.[14] In 1869, Wolstenholme invited Josephine Butler to be president of the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts that successfully campaigned for the repeal of the Acts in 1886. In 1883 Wolstenholme worked for the Guardianship of Infants Committee that became an act in 1886.

Personal life

Wolstenholme met silk mill owner, secularist and feminist Ben Elmy who's father Benjamin had moved from Southwold in Suffolk for work, when she moved to Congleton and in 1867 they set up a Ladies Education Society that was open to men. Elmy became active in the women's movement joining Wolstenholme's committees. Wolstenholme began living with Elmy in the early 1870s as they jointly followed the free love movement horrifying their devout Christian colleagues. When Wolstenholme became pregnant in 1874, her colleagues were outraged and demanded that the couple marry against their personal beliefs. Despite Wolstenholme and Elmy going through a civil registry office ceremony in 1874, Wolstenholme was forced to give up her job in London.

The Elmys moved to Buxton House, Buglawton and Wolstenholme gave birth to their son Frank in 1875. Although comfortably off by the standards of the day, the Elmys were by no means rich and Wolstenholme home schooled Frank. Wolstenholme spoke out against the Free Trade Law that was crippling the silk trade in Congleton and joined the Fair Trade League in 1881. The Elmy's silk mills went into liquidation in 1890 and Elmy retired due to ill health. The couple remained married until Elmy's death in 1906.

Wolstenholme died on 12 March 1918 and her funeral was held at the Manchester Crematorium.

Wolstenholme's achievements were recognised during her lifetime but she has since often been sidelined or even written out of histories of the women's movement.

Works

A prolific writer, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy wrote papers for the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, articles for the Westminster Review as Ignota, Shafts and national papers. Pamphlets concerning her campaigns were also publishes by organisations like the Women's Emancipation Union.[15] The most significant of her writing are the 'Report of the Married Women's Property Committee: Presented at the Final Meeting of their Friends and Subscribers' Manchester 1882. 'The Infants' Act 1886: The record of three years' effort for Legislative Reform, with its results published by the Women's Printing Society 1888. 'The Enfranchisement of Women' published by the Women's Emancipation Union 1892.

The British Library hold Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy's papers and those of the Guardianship of Infants Act and the Women's Emancipation Union.[15]

Also a writer of poetry Elizabeth Wolstenholme wrote 'The Song of the Insurgent Women' on 14 November 1906 and as Ignota 'War Against War in South Africa' 29 December 1899.[15]

Posthumous recognition

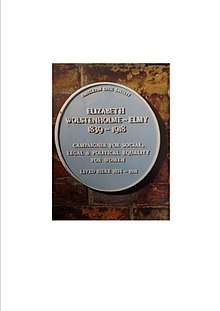

A blue plaque was erected for her at Buxton House, Buglawton by the Congleton Civic Society; it reads, "Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy 1839–1918 Campaigner for social, legal and political equality for women lived here 1874–1918".

Her name and image, and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters, are etched on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.[16]

References

Notes

- ↑ Crawford (2003), p. 225

- ↑ Stanley Holton, Sandra (2004), "Elmy, Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme (1833–1918), campaigner for women's rights", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 26 February 2015 (subscription required)

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 43

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 60

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 65

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 55

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 62

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 71

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 137

- ↑ Holton (2002), p. 76

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 152

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 190

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 185

- ↑ Wright (2011), p. 177

- 1 2 3 Wright (2011), p. 251

- ↑ "Millicent Fawcett statue unveiling: the women and men whose names will be on the plinth". iNews. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

Bibliography

- Crawford, Elizabeth (2003), The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928, Routledge, ISBN 1-135-43402-6

- Holton, Stanley (2002), Suffrage Days: Stories from the Women's Suffrage Movement, Routledge, ISBN 9781134837878

- Wright, Maureen (2011), Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy and the Victorian Feminist Movement the Biography of an Insurgent Woman, Manchester University Press, ISBN 9780719081095