Elizabeth Barton

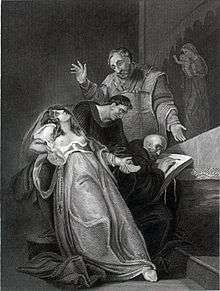

Sister Elizabeth Barton (1506 – 20 April 1534), known as "The Nun of Kent", "The Holy Maid of London", "The Holy Maid of Kent" and later "The Mad Maid of Kent", was an English Catholic nun. She was executed as a result of her prophecies against the marriage of King Henry VIII of England to Anne Boleyn.[1]

Early life

Little is known about her early life. She was born in 1506 in the parish of Aldington, about twelve miles from Canterbury,[2] and she appears to have come from a poor background. She was working as a servant when her visions began in 1525.

Visions

At the age of 19, while working as a domestic servant in the household of Thomas Cobb, a farmer of Aldington, she suffered from a severe illness and claimed to have received divine revelations that predicted future events, such as the death of a child living in her household or, more frequently, pleas for people to remain in the Roman Catholic Church. She also urged people to pray to the Blessed Virgin Mary and to undertake pilgrimages. Thousands believed in her prophecies and both Archbishop William Warham and Bishop John Fisher attested to her pious life.[3]

When some events that she foretold apparently happened, her reputation spread. The parish priest, Richard Masters, referred the matter to Warham, who appointed a commission to ensure that none of her prophecies were at variance with Catholic teaching. When the commission decided favourably, Warham arranged for Barton to be received in the Benedictine St Sepulchre's Priory, Canterbury.[2]

In 1528, she held a private meeting with Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the second most powerful man in England after Henry VIII, and she soon thereafter met twice with Henry himself. Henry accepted Barton because her prophecies then still supported the existing order. Her prophecies warned against heresy and condemned rebellion at a time when Henry was attempting to stamp out Lutheranism and was afraid of possible uprising or even assassination by his enemies.

However, when the King began the process of obtaining an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and seizing control of the Church in England from Rome, she turned against him. Barton strongly opposed the English Reformation and, in around 1532, began prophesying that if Henry remarried, he would die within a few months. She said that she had even seen the place in Hell to which he would go (Henry actually lived for a further 15 years).

Remarkably, probably because of her popularity, Barton went unpunished for nearly a year. The King's agents spread rumours that she was engaged in sexual relationships with priests and that she suffered from mental illness. Many prophecies, as Thomas More thought, were fictitiously attributed to her.[2]

Arrest and execution

With her reputation undermined, the Crown arrested Barton in 1533 and forced her to confess that she had fabricated her revelations.[1] However, all that is known regarding her confession comes from Thomas Cromwell, his agents and other sources on the side of the Crown.

Friar John Laurence of the Observant Friars of Greenwich gave evidence against the Maid and against fellow Observants, Friars Hugh Rich and Richard Risby. Laurence then requested to be named to one of the posts left vacant by their imprisonment.[4] She was condemned by a bill of attainder (25 Henry VIII, c. 12); an Act of Parliament authorising punishment without trial.

She was hanged and beheaded for treason at Tyburn,[1] along with five of her chief supporters:

- Edward Bocking, Benedictine monk of Christ Church, Canterbury

- John Dering, Benedictine monk;[5]

- Henry Gold, priest;[6]

- Hugh Rich, Franciscan friar;[6]

- Richard Risby, Franciscan friar.[6]

She was buried at Greyfriars Church in Newgate, but her head was put on a spike on London Bridge, the only woman in history accorded that dishonour.

Legacy

Churches such as the Anglican Catholic Church of St Augustine of Canterbury[7] continue to venerate her.

Popular culture

Her case is dealt with in the 2009 historical novel Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, and in its television adaptation, where she is played by Aimee-Ffion Edwards.

In A Man for all Seasons, she is referred to in an interrogation of Thomas More, as having been executed (Barton was executed about 15 months before More).[1][8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Elizabeth Barton" The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 18 Feb. 2013

- 1 2 3 Hamilton O. S. B., Adam. The Angel of Syon, The Life and Martyrdom of Blessed Richard Reynolds, Sands & Co., London, 1905

- ↑ A Popular History of the Reformation, p.177, Philip Hughes, 1957

- ↑ Camm O.S.B.,Dom Bede. "Blessed John Forest". Lives of the English Martyrs Declared Blessed by Pope Leo XIII, Vol. I, p.280, Longmans, Green and Co., London 1914

- ↑ Gasquet, Cardinal Francis Aidan. Henry VIII and the English Monasteries, G. Bell, 1906, p. 36

- 1 2 3 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Richard Risby". Newadvent.org. 1912-02-01. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- ↑ Church of St Augustine of Canterbury, Anglican Catholic, 2009–2010, retrieved 22 June 2010

- ↑ "Thomas More" The Catholic Encyclopedia

Bibliography

- McKee, John (1925), Dame Elizabeth Barton OSB, the Holy Maid of Kent, London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne .

- Neame, Alan (1971), The Holy Maid of Kent: The Life of Elizabeth Barton: 1506–1534, London: Hodder and Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-02574-3 .

- Shagan, Ethan H (2003), "Chapter 2: The Anatomy of opposition in early Reformation England; the case of Elizabeth Barton, the holy maid of Kent", Popular Politics in the English Reformation, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 61&ndash, 88 .

- Watt, Diane (1997), Secretaries of God, Cambridge, UK: DS Brewer .

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Barton, Elizabeth. |

- Watt, Diane, "Barton, Elizabeth (c. 1506–1534)", Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1598 .