Duke Ernest Gottlob of Mecklenburg

| Duke Ernest Gottlob | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

27 August 1742 Mirow, Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| Died | 27 January 1814 (aged 71) |

| House | House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| Father | Duke Charles Louis Frederick of Mecklenburg |

| Mother | Princess Elisabeth Albertine of Saxe-Hildburghausen |

Duke Ernest Gottlob Albert of Mecklenburg (27 August 1742 – 27 January 1814) was a member of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. As a younger son of Duke Charles Louis Frederick of Mecklenburg, Ernest was an elder brother of Queen Charlotte of the United Kingdom, who married King George III in 1761. Ernest followed his sister to England, where he unsuccessfully pursued marriage with the country's largest heiress, Mary Eleanor Bowes.

Enormous debt would later lead Ernest to attempt another marriage with a princess from the House of Holstein-Gottorp, but Charlotte managed to dissuade him. Ernest eventually became the military governor of Celle in the Electorate of Hanover, of which his brother-in-law George III was the head. Ernest died in 1814 at the age of 71 during the reign of George III but under the regency of his nephew George IV.

Life

Ernest Gottlob Albert was the seventh child and third son of Duke Charles Louis Frederick of Mecklenburg and his wife Princess Elisabeth Albertine of Saxe-Hildburghausen. Ernest's younger sister Charlotte married George III of the United Kingdom in 1761, and Ernest followed her to London.[2]

Ernest was described by novelist Sarah Scott as a "very pretty sort of man, with an agreeable person."[2] In March 1762 Ernest was said, according to Scott, to have "fallen desperately in love with" Mary Eleanor Bowes,[2] the richest heiress in Britain and possibly the richest in Europe.[3] Scott speculated that were the marriage to take place, Ernest would become even richer than his elder brother Adolphus Frederick IV, Duke of Mecklenburg. However, King George III disallowed the marriage, as he disapproved of his brother-in-law marrying someone not of royal blood.[2] Charlotte Papendiek, Queen Charlotte's wardrobe keeper, wrote many years later that the match would "have made him a Prince indeed; but as he was a younger brother, it might have disturbed the harmony of the house of Mecklenburg-Strelitz."[4][5] Ernest does not appear in Mary's letters, and it does not seem likely that his affection was reciprocated.[6]

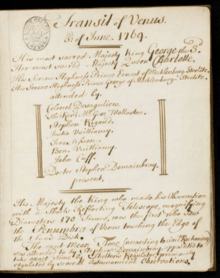

In late 1768 at Queen's House (now Buckingham Palace), Ernest was inoculated alongside his nephew Prince William (the future King William IV) against smallpox.[7] Ernest served as a sponsor and namesake for another nephew, Prince Ernest Augustus.[8] The following year Ernest and his brother George attended observations of the 1769 Transit of Venus at the King's Observatory in Richmond-upon-Thames. Charlotte remained close to all of her German relatives while married.[9] Like his brother Charles, Ernest benefited from Charlotte's marriage and gained promotion within the Hanoverian army, of which George III was the head.[10] Ernest eventually became the military governor of Celle, in Hanover, where he welcomed George III's exiled sister Queen Caroline Matilda upon the end of her marriage to Christian VII of Denmark.[9][11][12]

In 1782 Ernest attempted to enter into a marriage with a princess from the House of Holstein-Gottorp in an effort to pay his numerous debts. However, both the fact that he was a third son and the uncle of a male heir limited his appeal to potential dynastic alliances. Charlotte advised her brother to drop the match, as the dowry of the princess in question would not be enough to settle his debts; furthermore, neither she nor her husband would be able to help with his finances. She hoped that Christian VII of Denmark would provide a large dowry, as the princess was a member of his house, but concluded that no one would blame Ernest if he stopped pursuing the marriage. This frank advice was later praised by their brother Charles,[13] and Ernest never married.[10] He died on 27 January 1814 at the age of 71.

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Titles and styles

- 27 August 1742 – 27 January 1814: His Serene Highness Duke Ernest of Mecklenburg

Honours

Ancestry

Sources

- Grewolls, Grete (2011). Wer war wer in Mecklenburg und Vorpommern. Das Personenlexikon (in German). Rostock: Hinstorff Verlag. p. 2580. ISBN 978-3-356-01301-6.

References

- ↑ "Queen Charlotte with her children and brothers". Royal Collection. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Moore, p. 38.

- ↑ Moore, p. 30.

- ↑ Papendick, p. 75.

- ↑ Moore, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Moore, p. 39.

- ↑ Papendick, p. 41.

- ↑ Urban, p. 85.

- 1 2 Black, p. 312.

- 1 2 Campbell Orr, p. 369.

- ↑ Campbell Orr, p. 381.

- ↑ Wilkins, pp. 229, 242-243, 245.

- ↑ Campbell Orr, p. 376.

- ↑ Evans, Mark L. (1990). The Royal Collection: paintings from Windsor Castle. National Museums and Galleries of Wales. ISBN 0-7200-0344-X.

- ↑ Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 84.

Bibliography

- Black, Jeremy (2006). George III: America's Last King. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11732-9.

- Campbell Orr, Clarissa (2004). "Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of Great Britain and Electress of Hanover: Northern Dynasties and the Northern Republic of Letters". In Campbell Orr, Clarissa. Queenship in Europe 1660-1815: The Role of the Consort. Cambridge University Press. pp. 368–402. ISBN 0-521-81422-7.

- Moore, Wendy (2009). Wedlock: The True Story of the Disastrous Marriage and Remarkable Divorce of Mary Eleanor Bowes, Countess of Strathmore. New York: Three Rivers Press.

- Papendiek, Charlotte (1887). Court and private life in the time of Queen Charlotte: Being the Journals of Mrs. Papendiek, Assistant Keeper of the Wardrobe and Reader to Her Majesty, Volume 1. London: Spottiswoode and Co. ISBN 1-143-96208-7.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1852). The gentleman's magazine, Volume 37. London: J.B. Nichols and Son.

- Wilkins, William Henry (1904). A queen of tears: Caroline Matilda, queen of Denmark and Norway and Princess of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 2. London: Longmans Green and Co. ISBN 1-153-93838-3.