Dominican War of Independence

The Dominican Independence War gave the Dominican Republic autonomy from Haiti on February 27, 1844. Before the war, the island of Hispaniola had been united under the Haitian government for a period of 22 years when the newly independent nation, previously known as the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, was unified with Haiti in 1822. The criollo class within the country overthrew the Spanish crown in 1821 before unifying with Haiti a year later.

In 1844, the members of La Trinitaria chose El Conde, the prominent “Gate of the Count” in the old city walls, as the rallying point for their insurrection against the Haitian government. On the morning of 24 February 1844, El Conde rang with the shots of the plotters, who had emerged from their secret meetings to openly challenge the Haitians. Their efforts were successful, and for the next ten years, Dominican military strongmen fought to preserve their country's independence from their Haitian neighbors.[2]

Under the command Faustin Soulouque Haitian soldiers tried to gain back control of lost territory, but this effort was to no avail as the Dominicans would go on to decisively win every battle henceforth. In March 1844, a 30,000-strong two-pronged attack by Haitians was successfully repelled by an under-equipped Dominican army under the command of the wealthy rancher Gen. Pedro Santana.[2] Four years later, it took a Dominican flotilla harassing Haitian coastal villages, and land reinforcements in the south to force the determined Haitian emperor into a one-year truce.[2] In the most thorough and intense encounter of all, Dominican irregulars armed with swords sent Haitian troops into flight on all three fronts in 1855.[2]

Background

At the beginning of the 1800s, the colony of Santo Domingo, which had once been the headquarters of Spanish power in the New World, was in its worst decline. Spain during this time was embroiled in the Peninsular War in Europe, and other various wars to maintain control of the Americas. With Spain's resources spread among its global interest, Santo Domingo and other Caribbean territories became neglected. This period is referred to as the España Boba era.

The population of the Spanish colony stood at approximately 80,000 with the vast majority being European descendants and free people of color. For most of its history, Santo Domingo had an economy based on mining and cattle ranching. The Spanish colony's plantation economy never truly flourished, because of this black slave population had been significantly lower than that of the neighboring Saint-Domingue, which was nearing a million slaves before the Haitian Revolution.

At the time Haiti had been more economically and militarily powerful and had a population 8 to 10 times larger than the former Spanish colony, having been the richest colony in the western hemisphere before the Haitian Revolution. Dominican military officers agreed to merge the newly independent nation with Haiti, as they sought for political stability under the Haitian president Jean-Pierre Boyer, who belonged to Haiti's elite mulatto class and was seen as an ally at the time. However, due to the Haitian government's mismanagement, heavy military disputes, and an economic crisis the Haitian government became increasingly unpopular. A conspiracy of Dominicans in Santo Domingo called La Trinitaria hastened the end of the Haitian occupation.

Ephemeral independence

Late in 1821 the leader José Núñez de Cáceres proclaimed Santo Domingo's adhesion to the new “Republic of Gran Colombia”, created by Simón Bolívar, but the determination of the island elite to perpetuate their privileged status by maintaining intact all colonial-era institutions such as social hierarchy, land titles, and slavery doomed this limited experiment in liberty to failure two months later.[3]

Unification of Hispaniola (1822-1844)

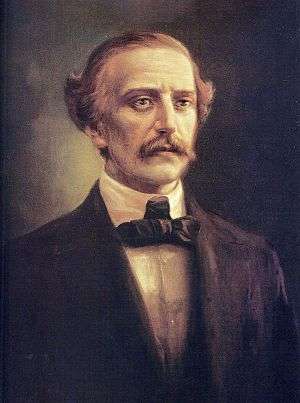

_Portrait.jpg)

A group of Dominican politicians and military officers had expressed interest in uniting the entire island, while they sought for political stability and support under Haiti, which at the time was still seen as having a great deal of wealth and power. Haiti had been by far the richest colony in the western hemisphere and was known as the Pearl of the Antilles.

Haiti's president, Jean-Pierre Boyer, conducted the third military campaign of Santo Domingo, this one was met with resistance, partly due to the previous invasion experiences, and because of Haiti's overpowering military strength at the time. The population of Haiti had a ratio of 8:1 compared to the Dominican population of 1822.

On February 9, 1822, Boyer formally entered the capital city, Santo Domingo, where he was met and received by Núñez who handed to him the keys of the Palace. Boyer then proclaimed: "I have not come into this city as a conqueror but by the will of its inhabitants". The island was thus united from "Cape Tiburon to Cape Samana in possession of one government."

Eventually, the Haitian government became extremely unpopular throughout the country. The Dominican population grew increasingly impatient with Haiti's poor management and perceived incompetence, and the heavy taxation that was imposed on their side. The country was hit with a severe economic crisis after having been forced to pay a huge indemnity to France. A debt was accrued by Haiti in order to pay for their own independence from the European nation; this would give rise to many anti-Haitian plots.

Resistance

In 1838 Juan Pablo Duarte, an educated nationalist, founded a resistance movement called La Trinitaria ("The Trinity") along with Ramón Matías Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez. It was so named because its original nine members had organized themselves into cells of three. The cells went on to recruit as separate organizations, maintaining strict secrecy, with little or no direct contact among themselves, in order to minimize the possibility of detection by the Haitian authorities. Many recruits quickly came to the group, but it was discovered and forced to change its name to La Filantrópica ("The Philanthropic"). The Trinitarios won the loyalty of two Dominican-manned Haitian regiments.[4]

In 1843 the revolution made a breakthrough: they worked with a liberal Haitian party that overthrew President Jean-Pierre Boyer. However, the Trinitarios'[5] work in the overthrow gained the attention of Boyer's replacement, Charles Rivière-Hérard. Rivière-Hérard imprisoned some Trinitarios and forced Duarte to leave the island. While gone, Duarte searched for support in Colombia and Venezuela, but was unsuccessful. Upon returning to Haiti, Hérard, a mulatto, faced a rebellion by blacks in Port-au-Prince. The two regiments of Dominicans were among those used by Hérard to suppress the uprising.[4]

In December 1843 the rebels told Duarte to return since they had to act quickly because they were afraid the Haitians had learned of their insurrection plans. When Duarte had not returned by February, because of illness, the rebels decided to take action anyway with the leadership of Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, Ramón Matías Mella, and Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle-rancher from El Seibo who commanded a private army of peons who worked on his estates.

War of Independence

On February 27, 1844, some 100 Dominicans seized the fortress of Puerta del Conde in the city of Santo Domingo, and the following day the Haitian garrison surrendered.[4] As these Haitian troops withdrew to the west side of the island, they pillaged and burned.[4] Mella headed the provisional governing junta of the new Dominican Republic. On March 14, Duarte finally returned after recovering from his illness and was greeted in celebration. Haitian Commander, Charles Rivière-Hérard, sent three columns totaling 30,000 men to crush the Dominican uprising.[6] In the south, Hérard was checked by Dominican forces led by Pedro Santana at Azua on March 19. In the north, General Jean-Louis Pierrot and 15,000 Haitians were repelled in an attack on Santiago by the garrison commanded by José María Imbert.[6] As the Haitians retreated, they laid waste to land.[4]

Meanwhile, at sea, the Dominican schooners Maria Chica (3 guns), commanded by Juan Bautista Maggiolo, and the Separación Dominicana (5 guns), commanded by Juan Bautista Cambiaso, defeated a Haitian brigantine Pandora (unk guns) plus schooners Le signifie (unk guns) and La Mouche (unk guns) off Tortuguero on April 15.[4]

On June 17, 1845, the Dominicans, only a little over a year after winning independence from Haiti, invaded their former master in retaliation for Haitian border raids.[6] The invaders captured two towns on the Plateau du Centre and established a bastion at Cachimán.[6] Haitian President Jean-Louis Pierrot quickly mobilized his army and counterattacked on July 22, driving the invaders from Cachimán and back across the frontier.[1] In the first significant naval action between the Hispaniolan rivals, a Dominican squadron captured 3 small Haitian warships and 149 seamen off Puerto Plata on December 21.[1]

On March 9, 1849, President Faustin Soulouque of Haiti led 10,000 troops in an invasion of the Dominican Republic. Dominican General (and presidential contender) Santana raised 6,000 soldiers and, with the help of several gunboats, routed the Haitian invaders at El Número on April 17 and at Las Carreras[7] on April 21–22.[8] In November 1849, a small naval campaign was undertaken in which Dominican government schooners captured Anse-à-Pitres and one or two other villages on the southern coast of Haiti, which were sacked and burned by the Dominicans.[9] The Dominicans also captured Dame-Marie, which they plundered and set on fire.[10]

By late 1854 the Hispaniolan nations were at war again. In November, 2 Dominican ships captured a Haitian warship and bombarded two Haitian ports.[1] In November 1855, Soulouque, having proclaimed himself Emperor Faustin I of a Haitian empire which he hoped to expand to include the Dominican Republic, invaded his neighbor again, this time with a ravaging and looting army of 30,000 men marching in three columns.[1] But again the Dominicans proved to be superior soldiers, defeating Soulouque's army, which vastly outnumbered them.[11]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clodfelter 2017, p. 302.

- 1 2 3 4 Knight 2014, p. 198.

- ↑ Marley 2005, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scheina 2003.

- ↑ The members of La Trinitaria.

- 1 2 3 4 Clodfelter 2017, p. 301.

- ↑ The battle opened with a cannon barrage and devolved into a hand-to-hand bloodbath. Neither side took prisoners.

- ↑ As the remnants of the Haitian army retreated along the southern coastal road, they were under fire from a small Dominican squadron. The Haitians hastily burned the town of Azua and the hamlets of Neiba, San Juan, and Las Matas.

- ↑ Schoenrich 1918.

- ↑ Léger 1907, p. 202.

- ↑ It was the last Haitian invasion, but Haiti did not formally recognize the independence of the Dominican Republic until 1874.

References

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). McFarland.

- Schoenrich, Otto (1918). Santo Domingo: A Country with a Future. Library of Alexandria.

- Marley, David (2005). Historic Cities of the Americas: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars. Potomac Books.

- Knight, Franklin W. (2014). The Modern Caribbean. UNC Press Books.

- Léger, Jacques Nicolas (1907). Haiti: Her History and Her Detractors. The Neale Publishing Company.