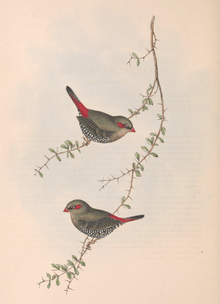

Red-eared firetail

| Red-eared firetail | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Estrildidae |

| Genus: | Stagonopleura |

| Species: | S. oculata |

| Binomial name | |

| Stagonopleura oculata | |

Red-eared firetail and boorin are common names for Stagonopleura oculata, a small finch-like species of birds occurring at dense wetland vegetation in coastal regions of Southwest Australia. Their appearance is considered appealing—with eye-like spots, distinctive black barring and vivid crimson marks—although they are usually only glimpsed briefly, if at all, as they move rapidly and discretely through their habitat. Males and females, similar in colouring, bond as lifelong pairs that occupy a territory centred on their roosting and brooding nest site. They are rare in captivity, being neither recommended nor generally permitted, as they require expertise and a large specialised environment to maintain their secretive habits; however, the observations in avicultural literature have contributed greatly to the knowledge and research of the species. Despite their shyness toward other birds and people, they are known to be less so when venturing out to bird feeders.

Taxonomy

The species Stagonopleura (Zonaeginthus) oculata (Quoy & Gaimard, 1830) is allied to the family Estrildidae of the avian order Passeriformes.

The first description of the species—as Fringilla oculata—was by French naturalists Jean René Constant Quoy and Joseph Paul Gaimard, assigning them to the once larger genus Fringilla (L. finch) of Linnaeus.[2][3] This was published in the zoology volume of Dumont d'Urville's 1830 account of the expedition aboard the Astrolabe, based on a specimen they had collected at King George Sound.[4][5] This preceded the entry Estrelda oculea in Gould's Birds of Australia (1848), the later description making an unnecessary emendation to the spelling of the epithet.[2] Gould's Handbook (1865) defers to Zonæginthus oculeus, giving a citation to the 1853 circumscription of Cabanis.[6][7] The classification as Zonaeginthus oculatus is given with Neville Cayley's depiction of the species, with the explanation of the epithet as derived from the Latin term oculatus, 'marked with eyes'.[8] Prior to its separation to the genus Stagonopleura the species was classified as Emblema oculata.[9]

No infraspecific variation for the species is cited in avicultural or ornithological literature. A typical description of a new subspecies, Zonaeginthus oculatus gaimardi, published by G. M. Mathews in 1923 is only mentioned as a synonym for the species.[2] While no subspecies are recognised, several varying characteristics in the population have been identified: a sub-population near the coast from Cape Arid to Cape Le Grand and islands of the Recherche Archipelago are notably paler and said to be geographically isolated by a strip of arid land twenty kilometres wide, Johnstone and Storr (2004) also reported an individual at Ravensthorpe that was found to have pinkish tips to feathers on its breast.[4] The description as a subgeneric arrangement, Stagonopleura (Zonaeginthus) oculata, was published in 2006, confirming the presumed alliance to its sister species Stagonopleura (Zonaeginthus) bellus—the beautiful firetail—that was suggested by Gould and subsequent authors.[2][6]

Earlier names for this population of birds in the Nyungar language were recorded by John Gilbert and published in Gould's Birds of Australia and Handbook. Similar names with variant spellings were given for the districts of King George Sound, Darling Range, and Perth by Serventy and Whittell in their mid-twentieth century Handbook (1948). A recommended orthography and pronunciation list of all published names has proposed boorin, dwerdengolngani and djiri in preference to later vernacular.[10] Other names include variations red-eared firetail finch, Western firetail, red-eared finch and the ambiguous zebra finch,[11][12] the IOC World Bird List recommended "Red-eared Firetail" as the preferred English name and orthography.[13] Gilbert, via Gould, reported the Swan River colonists had named the bird 'native sparrow'.[6] The attraction of the species to seed bearing cones of sheoak (Allocasuarina) inspired a local name of 'casuarina finch' in the Pemberton area.[4]

Description

A small grass-finch with black-barred and white-spotted plumage, distinguished by its scarlet bill, black 'mask', and bright crimson red patch behind the eye and at the rump. The plumage of the upper parts is olive-brown, the breast is buff-brown, both of which are thinly barred black. White spots appear on the blackish underparts. The female closely resembles the male, except when his colouring intensifies in the breeding season.[12]

The adult plumage is crossed with black vermiculated lines, finely at the nape and crown and more strongly at the scapular feathers, upper-wing coverts, back, and the mantle; these sinuous black markings appear on otherwise greyish-brown upperparts. A similar patterning, dusky black, is finer at the brown throat and cheek, and bolder at the grey-buff of the foreneck. The feathers of the underparts—undertail coverts, abdomen and flank—are white with a black margin and barring that outline the distinct spots. The light brown thigh is slightly crossed with black. Paler lines cross the brown coverts under the tail. The secondary flight feathers and coverts are also greyish brown, with grey-black barring. The primaries and their coverts are dark brown, the outer primaries have a thin margin of a paler brown. A deep shade of crimson is apparent on the rump and tail coverts.[4] A thin black band extends across the frons, broadening at the lores and circling the eyes to give a masked appearance,[14] contrasting the distinctive patch of crimson at the ear coverts and scarlet of the bill; these are found to be comparatively larger in males when closely observed.[12][4] The colour of the tail feathers is a dusky shade of brown with fine black barring, the central tail feathers become crimson toward the coverts.[4]

Description of the iris is as red or dark brown, the eye-ring pale blue, the legs as dark or pink-brown.[12][4] The bill of both sexes is red, although a coating on the bill of the male intensifies its colour during the breeding season. The average size of the adult is around 125 millimetres in length. The weight of males is between 11.4 and 16.0 grams, females have a narrower range between 12.5 and 13.6 grams. Using a sample of thirty males and fifteen females, the average length in millimetres of the wing is 56.2; bill 11.8; tail 43.7; and tarsus 17.0 for the male, the female is wing 56.4; bill 11.6; tail 42.4; and tarsus 17.4 millimetres.[4]

The juvenile plumage resembles the adult, without the deep crimson ear patch and spotted belly.[11] When observed in captivity the white spots appeared first, beginning at the flank, the red ear was the last characteristic to emerge, The vermicular bars of the adult are absent at the nape and crown, and more subdued on the rest of the upper-parts. The black at the eyes and lores is absent or nearly so, the distinct red of the upper tail coverts and rump is duller, and underparts are lighter, buff coloured, and mottled rather than spotted. Immature birds usually attain adult plumage within four months, this period is extended if born late in the breeding season. The juvenile's bill begins as a brownish black colour, becoming scarlet between fourteen and twenty two days after fledging, and blue luminous tubercules are evident at the gape. The legs are a duller shade of brown, the naked and white eye-ring is only slightly blue.[4]

The shell of egg is pure white, smooth and finely grained, with a lustrous salmon-pink tone produced by the contents.[12] The eggs were described as twelve by sixteen millimetres in size and oval in shape by Alfred North (1901–14),[15] Forshaw gave the form as 'ovate to elliptical ovate', a lack of gloss and a sample of forty six specimens from nine clutches noted as 15.9 to 17.8 by 11.9 to 13.2 millimetres to give average dimensions of 16.6 by 12.4 mm (Johnstone & Storr, 2004); a clutch of six eggs at Torbay (1959) and another of five closer to Albany (1967) were recorded as larger than this average size.[4]

Ecology

A seed eating estrildid, discrete and unusually solitary for an Australian grass finch species. They often remain unobserved in their dense habitat while foraging in the lower storey, their presence being revealed by distinctive calls, and most frequently seen when perched high on the limb of a tree such as marri.[12][14] Red-eared firetails form mated pairs rather than grouping, their individual range is an area around one to two hundred metres across; they may join others while feeding where their territories overlap. Earnest defence of sites only occurs close to the nest, so boundaries between pairs may intersect without incident.[11]

It has an estimated global extent of occurrence of 20,000–50,000 km2.

Distribution

Endemic to the south-western corner of Australia. The species is uncommon to scarce, restricted by its range and removal of habitat, though it may be locally common in its undisturbed environment, which is typically heavy forests and dense heaths around gullies, rivers and swamps. The population density increases toward coastal areas of its range, especially at the south.[16] The distribution range along the southern coast extends past Esperance to the east.[11] From the southern coast the species occurs as far north as Cape Naturaliste, Bridgetown, Lake Muir, the Stirling Range, Gairdner River (Calyerup) and the Ravensthorpe Range, and is present off the coast at Bald and Coffin Islands,[17] and on islands of the Recherche Archipelago.[8] Records are more scarce north of Wungong Creek in the Darling Range and at the Stirling Range, and there is a decreasing population density toward inland regions of Fitzgerald River National Park and Ravensthorpe Range.[17]

The IUCN redlist (2016) has classified the species as being of least concern,[18] citing the entry in Stephen Garnett's list of threatened and extinct birds (1992) that notes while much of its habitat is degraded by salinity or destroyed by changes in agricultural and water management, the usually sedentary habits of the species have not impeded their dispersal within their distribution range and the population was suspected to be stable.[19]

Changes in land use, such as clearing around frontage at permanent water, has resulted in species becoming absent where it had been previously recorded. Gould described the species as "abundant" around the Swan River colony in 1848, some twenty years after settlement of the region.[20] Serventy noted it had disappeared from areas near Perth and Pinjarra by the mid-twentieth century, perhaps from the Swan Coastal Plain altogether, though it had persisted at gullies around Mundaring Weir in the Darling Range.[12] The Records (1991) of the Western Australian Museum gave a northern most location of Glen Forrest in the Darling Range to an area near North Bannister and Mt Saddleback, and confirmed their continued absence from the Swan Coastal plain.[17] However, occasional reports of sightings in the largely cleared region are cited, HANZAB notes two seen at Canning Mills in 1997.[4]

The type locality, King George Sound, was the source of a later collection made by George Masters for the Australian Museum in 1869. A report on the species for British journal Ibis by Tom Carter in 1921 noted the occurrence of the species at swamps, common at those dominated by paperbark (Melaleuca) near Albany (1913) and located nests at a wetland near Cape Leeuwin (1916); records are also given for sites around Lake Muir (1913) and at Warren River (March, 1919) in dense scrub below karri forest.[21] Carter had earlier given his observations between Albany and Cape Naturaliste, and noted it was common at springs at limestone hills near Margaret River, Western Australia; he considered a specimen he shot in a karri tree as outside its usual habitat of the dense understorey.[15]

Habitat

The species is associated with dense vegetation at forest, paperbark swamps, heathland, river frontage and gullies. They often occur in habitat containing the sedge Lepidosperma tetraquetrum and sheoak tree, gulli (Allocasuarina fraseriana), as the seed of these plants is a favoured part of their diet.[17] The usual forest and woodland habitat is jarrah and other eucalypts, the dense thickets in karri and midstorey vegetation of marri, or sheoak and paperbark swamps at the south coast.[22] Ornithological surveys of previous study sites at the Darling Range found greater numbers in habitat closer to Wungong Dam than at its tributaries and surrounding valleys. Casual observations are frequently made close to the carparks at Little Beach, Two Peoples Bay and Porongurup nature reserves, and amongst the heath of the headland at Cape Naturaliste.[23]

The species occupies a similar niche to Stagonopleura bella, the beautiful firetail, within their respective distribution range.[23]

Associations

Immelmann's remarks on the solitary habits of individuals and mated pairs, in contrast to the gregarious habits of the related beautiful firetails, is largely confirmed by later field researchers, aviculturalists and casual observations. He noted that a few young birds may appear together, in jarrah forest six immature birds might appear in a group, perhaps driven from their parents territory. Pair bonding is maintained until the death of an individual, and mates can be selected before fully mature. The reclusive behaviour is not displayed outside its native habitat, and the species has been observed feeding with Western rosellas (Platycercus icterotis) and splendid fairy wrens (Malurus splendens) at parkland and gardens. Records of the species being tamely drawn to seed at tourist sites include this regularly occurring at Cape Naturaliste, and a casual observation in 2010 with Western rosella and rock parrots (Neophema petrophila) at Nornalup. Their discretion in their native habitat, however. was shown in a census (Fitzgerald River, 1994–97) that mist-netted thirteen individuals and failed to make any visual sighting. The nestlings being observed at Immelmann's Wungong site were taken by a local python, Morelia spilota.[4]

The trees of its wooded habitat are eucalypts, Eucalyptus marginata (jarrah), E, diversicolor (karri) and Corymbia calophylla (marri), she-oaks Allocasuarina and paperbark species of Melaleuca.[24]

The species is recorded in captivity as responding to alarm calls of neighbouring Malurus splendens by seeking refuge in the undergrowth of their aviary.[4]

Behaviour

The first study of the species in the field was by John Gilbert, whose notes were printed verbatim in Gould's Handbook (1865) and cited by North (1914)[15] and others; the accuracy of his reports has been verified in subsequent research.[4]

"it is a solitary species and is generally found in the most retired spots in the thickets, where its mournful, slowly drawn-out note only serves to add to the loneliness of the place. Its powers of flight, although sometimes rapid, would seem to be feeble, as they are merely employed to remove it from tree to tree. The natives of the mountain districts of Western Australia have a tradition that the first bird of this species speared a dog and drank its blood, and thus obtained its red bill." Gilbert, J., Gould's Handbook (1865)[6]

An important source of information on the species resulted from a 1960 study undertaken by Klaus Immelmann at Wungong Gorge, a broad depression around permanent water with dense scrub interspersed with marri, where he observed their feeding and breeding habits. Knowledge of their behaviour in the field is also supported by the published observations of specialist breeders.[4]

The ability to negotiate the dense vegetation of its habitat was remarked on by Immelmann as more adept than other Australian grassfinches. They climb vertically by releasing their feet with forward movements to ascend with a pivoting action, using the same method on horizontal stems and to descend through branching and foliage. When moving downward the may nod forward to hang from the perch before releasing their grasp to rapidly pivot upright.[4]

Observations of the species is usually when it is disturbed, the individual will fly to a high perch and call briefly before relocating to another part of its territory.[22] The behaviour in captivity is also reported by aviculturalists as mostly secretive and they will become anxious in response to strangers. A familiar person will be tolerated and watched, and they will eventually resume their movement about the cage. The individuals exhibit a tapping habit when closely observed, using the bill to strike twice or wipe across each branch it lands upon. The species is most active in the early morning, in movement and vocalisation, and curious about any novelty in their aviary. Adults and young use their aviary's roosting nest at night. They are seen bathing themselves in water for extended periods, becoming completely immersed at times.[4]

Feeding

Amongst Immelmann's observations is the habit of the species to avoid the ground, preferring a perch at lower or fallen branches and twigs when feeding in the understorey. Seed is extracted from grasses by using the bill to bend the stem within reach of the foot, which then draws the seedhead through the bill before releasing it to harvest the next stem. The seed of taller plants is accessed by perching close to the source and taking them into the bill directly. When taking to the ground to feed, again using its foot and beak to bend the grass sheaths, it will frequently regain a higher vantage point to survey the surroundings. A favourite seed is those of sedge species Lepidosperma, in addition to other plants in its habitat. The feeding from plants at the northern study site at the Darling Range noted seeds of species Lepidosperma angustatum and Bossiaea (pea family Papilionaceae), and karri hazel ("Trymalium spathulatum") fruits. Other favoured species include the sedges, Lepidosperma tetraquetrum and Lepidosperma squamatum, grasses of genus Briza, and the cones of Allocasuarina; an early observation of the species dissecting casuarina cones for seed was misinterpreted as a search for insects.[4]

Specimens in captivity will eat green leaf matter, supported by an observation of probable feeding on clover leaves in a maintained lawn at Mundaring Reservoir. Captives have also been found to favour seed of Lepidosperma gladiatum, ripened or not, twisting open the tough casing with a motion of their head. The species is attracted to the seed available in aviaries of parrots, bird feeders in suburban gardens, and managed parkland, usually singularly or in pairs and perhaps with other bird species.[4]

Vocalisation

Up to five communication calls had been recognised by the late twentieth century.[11] The volume of their calls is low, so only heard nearby, the communication at the nest-site is very soft.[25]

An 'identity call' was described by Immelmann as a drawn out oowee with a ventriloquial character that disguises its location. This call is delivered with little evident movement, except at the throat, and assuming a pose with the head held up, a little forward, and the bill closed or only slightly parted; it may delivered once or up to twenty times in succession. A presumed function of this call, regularly used during its activities in the non-breeding season, is contact with the partner across their territory. The variable tune of the identity note and lengths of rests, one to three times the note's value in each call, is repeated in turn by their mate after several seconds, the communication continuing for a few minutes and reëstablished around every half hour. The tone of its call is reported in captive pairs to be higher pitched with the male and quavering in the female during breeding. A trembling attempt at the identity note is made by individuals shortly after fledging, likened to a broken toy whistle, the faltering call of the juveniles only losing their quaver at maturity. The parenting call is softer and sonorous, the female's voice is distinguished by an insistent quiver as they attend to fledglings, who respond with a sharp and low twitter.[4]

An exchange of calls was described in Immelmann's study, this 'intimate nest' vocalisation is begun with the arriving parent, who with a closed bill, wings twitching at each note, delivers a twit-twit announcement at the entrance of the nest. The reply from the brooding bird within is a drawled syllable tweet- … and sharply rapped tit-tit-tit.[4]

Another phrase is termed the 'nest site' call, which may opened with a shorter, more richly toned, version of the 'identity call' oowee, and five quick notes of u-u-u-u-u that becomes less insistent. A similar call is reported in adults and juveniles of aviaries throughout the day a seasons, with a subsequent phrase of a very soft huh-huh-huh delivered with the breast and throat expanded; a reported variation, three syllables of a zst sound, may be juvenile attempts to produce this phrase. A more intimate 'conversation call' is also noted in captivity, only discernible within a metre, that repeats a sound transcribed as qwirk or qwark; Immelmann pronounced that this seemed identical to the vocal habit of finches that is termed as a 'communication call'. The aviculturalist Pepper also described an 'alarm call', given in response to perceived threats to its young, that resembled one of "a broody [domestic] hen being removed from her nest". His observations of young in an aviary gives a report of their 'feeding call', a grating sound that slightly increases in pitch after fledging; the young signal to the parent with a repeated plea of chik and produce the feeding call when attended.[4]

The song of the species was reported in captivity when they were courting or alone, the sequence begins with a whistle like a flute, a note extending over four loud pulses, and ending in repeated grasping sounds. A loud and warbling attempt at this song by a captive, fifteen days after fledging, was observed at a high perch of the cage.[4]

Reproduction

Pairing of individuals occurs in the first year, this bond remains throughout their life.[4] The breeding season is October to November, perhaps extending to January.[17] The nest is carefully and tightly woven from grassy materials, reinforced with the green tips of plants, forming a rigid down facing spherical construction. The nest's size, like that of the sister species Stagonopleura bella, is the largest of grassfinches in Australia.[4] The number of eggs in the clutch is between four and six,[12] which hatch after an incubation period of fourteen days. The total time of incubation duty is equal in length for each parent, the alternation of periods attending the eggs occur after one and a half to two hours and their customary exchange of the 'intimate nest' calls. Males may arrive at the nest with a feather when assuming his shift, continuing this practice for eight days after the eggs hatch. Both parents remain in the nest when relieved, for several seconds or a up to half an hour when young emerge from their eggs, and remain tightly huddled during the night. Attempts to violently dislodge nesting birds, testing their resolve to remain with progeny, were unsuccessful. After the eggs hatch the shells are removed from the nest to be dropped some thirty to forty metres away. The young born in aviaries remain in the nest until they fledge, recorded as between two to three weeks, and both parents continue closely attending to care and feeding after they emerge. A caged bird was observed participating in bathing activity one week after fledging.[4]

Courtship and breeding habits recorded at Immelmann's site in 1960 are supported by later observations and cited in ornithological literature (Storr and Johnstone, 2004; Forshaw and Shephard, 2012; et al). The male selects a nesting site and presents an overt display—presumably to entice a female—by adopting an inflated pose and issuing a rendition of its 'identity call', interspersing this with hopping movements about the branches. The male may continue these gestures for up to forty five minutes, perhaps utilising a length of grass, two hundred to four hundred and fifty millimetres, that appears to be pierced rather than held at the point of the bill by a fibre that he has been slightly torn near the base. The grass prop—symbolic of nest construction and copulation according to the ethological interpretation of Immelmann—is dangled downward as the males presents the prospective site. The stem can be lost in high wind as it sways beneath while moving around the site, if snagged by the undergrowth the male giving a quick sideways tug of the head. If the gestures fail to solicit the interest of a female the suitor either selects another site or another stem of grass before resuming his efforts. The performance is abandoned when a female responds by her investigation of the display area, and he retires to the precise location being proposed; at this position, usually a discrete fork in the branches, he drops his grass-stem prop and utters his 'nest-site call'. If persuaded the female moves near or onto the position indicated by the male, or departs if dissatisfied to await the next proposal.[4]

The site of the nest was given in an early report as within a prickly hakea (Hakea sp.) at the coast, a tree or sapling is selected in forest or woodland regions. In forest the nesting site is hidden high in a tall tree—marri, jarrah or yate—or the branches of shrubs in the midstorey, species of Melaleuca, hakea or banksia, or amongst creeper or mistletoe.[4] A nest near the town of Denmark, observed by Robert Hall for several days in 1902, was placed between banksia and grasstrees (Xanthorrhoea).[26] The nests of the previous season observed at Cape Leeuwin by Carter (1921), where local boys said they appeared every year, are described as slightly domed structures composed of fibre and fine grasses.[21] This followed a similar report by Carter (North, 1914) on a nest from the previous season in September at the paperbark swamps near Albany, located at a height of ten feet in tall scrub and 'closely resembling those of the chestnut-eared finch' (Taeniopygia guttata castanotis, Australian zebra finch). While he did not make observations in the breeding season at Albany, he estimated this to be November to December and reported seeing fledglings being fed in January of 1905 and 1909.[15]

The construction of the nest varies in form, resembling a bottle or retort, spherical or globular, with a long and narrow entrance that often faces downward. The external size of this nest range from 160 to 195 millimetres in height, a width of 120 to 104 mm, and between 220 and 320 mm in total length. The material used for construction of the nest is mostly fresh grass stems, clipped at the base and held vertically in the bill of the male for delivery to the female who performs the building role. At the peak of this activity a male is delivering one stem every thirty seconds. The interior is lined with feathers and other plant material, this contains a two part spherical breeding chamber that contains a finer walled cup-shaped nest. The material utilised in the outer face is often wiry and fibrous, and difficult to prise apart, the interior is generally made of soft and green grass. Examination of the elaborate nest construction indicates a significant investment of energy and time for a small bird. Four nests at the Wungong study site (Immelman, 1960) were found, aside from the lining, to contain eight hundred to over one thousand pieces of material. The outer parts of each nest contained 400 to 550 pieces, stripped from Thysanotis patersonii (twining fringe-lily), one measuring 89 cm with fine tendrils attached that were around 5–35 cm in length. These strips were between 40 and 50 centimetres at the exterior of the structure, those in the tunnels becoming progressively shorter at the interior, around fifteen to twenty centimetres in length. Tunnels were made of 150 to 180 pieces strips of the same material. The central nests were composed of 230–360 soft stems from grass species Stipa elegantissima, the maximum length of 200 mm progressively shortening to 50 mm at the interior. The lining also contained over three hundred feathers from a rosella (Platycercus icterotis) that had died in the vicinity, along with large amounts of downy plant material, bringing the total number of items delivered and assembled to over two thousand.[4]

A nest site was observed by Thomas Burns at Cape Riche in 1912, from this a collection of four well developed eggs were procured on the 28th of September for an egg collector in New South Wales; these specimens were examined in North's Nests and eggs of birds found breeding in Australia and Tasmania (1901–14).[15]

Captivity

The red-eared firetail is regarded as an attractive but unpopular bird in aviculture. They are rare and expensive, requiring permits that were restricted to specific research purposes, and remain hidden in an elaborate aviary that simulates their habitat.[27] There is no record of the species held in an aviary before 1938, Cayley noting their absence from the literature in 1932, the first was published in the British Avicultural Magazine. The author, H. V. Highman of Perth, had contracted a collector who travelled two hundred kilometres to trap and supply him with around twenty five birds. Highman maintained his personal collection of three pairs in a large aviary, measuring six by twenty four by twenty one metres, with living plants and several other bird species, including the beautiful firetail, Stagonopleura bella. A single specimen was sent to noted aviculturalist Simon Harvey in South Australia, though it did not survive long after. Highman reports that eight pairs were sent to Germany in 1933.[4]

Mating pairs require their own aviary, large enough to accommodate trees 2.5 metres tall. Aviaries reproducing a suitable habitat, an understorey of grasses and shrubs beneath a canopy of tree species Kunzea, Callistemon, Grevillea or Melaleuca has been successful in accommodating breeding pairs.[27] Hutton densely planted aviaries with these trees and shrubs in her research, using pampas, Johnson and Geraldton grasses with clover and Phalaris species. Leaf litter was placed around plants to replicate the diversity and density of its native habitat.[4] The breeding season can occur between July and January, during which the mating pairs aggression toward all other individuals intensifies. The difficulty in distinguishing males is resolved by careful observation of the deeper red of the coverts at the ear preceding the breeding period, or calls and behaviours at this time. The male initiates copulation by selecting a piece of grass, then a small flexible branch, to present for the partner, energetically bouncing with feathers fluffed up. The female reciprocates his display with the tail quivering while squatting. The arrangement of the nest and site is similar to those in its native environment. The seeds available from the plants of the aviary are supplemented with panicum, canary and millet, the birds forage for these and live insects in the foliage and floor of its artificial habitat.[27]

The species has been bred in captivity since 1938, the first record was the discovery of young produced by caged specimens.[28] The Western Australian aviculturalist, Alwyn Pepper, began a breeding program in 1962, using eggs obtained from a fallen nest in its native habitat.[4] The clutch was incubated by Bengalese finches (Lonchura domestica), and a breeding pair were reared to successfully produce offspring within the first year. Pepper's work on this breeding program was acknowledged with an award from the Avicultural Society of Australia in 1986. Research into captive breeding was continued in Western Australia by Rosemary Hutton.[27] The Perth Zoo established a breeding program in the 1980s, using four legally captured specimens to produce forty birds. A pair from the zoo's program were supplied to aviculturalist David Myers in New South Wales, producing four young in 1992. Some records of the species in aviaries outside Australia are anecdotal, reports stating they were seen in Belgium avaries and in other parts of Europe. In 1971 a group of twenty birds was sent to the University of Zurich, these had a low reproduction rate and eventually died of hepatitis. The species has only been available to aviculture in Australia when legally permitted, although restrictions that were later relaxed, and not known to have been obtainable elsewhere; it has never been legally imported into North America.[4] The red-eared firetail is regarded as unsuitable for any aviculturalist but a finch specialist willing to dedicate resources for little return, a view long held by its breeders; this general advice was reiterated by Myers in 1987 and for twenty years thereafter. The species is comparatively expensive to purchase.[4] The secretive habits and dense habitat required also make it unsuitable for exhibition at zoological gardens.[4] No mutations have been reported in the captive population.[27] As of 2011, the species remained very rare in captivity, state authorities giving statistics across several decades of few or none being held; a national census by a finch association gave a total of 38 birds for that year. Records of breeding in captivity are scarce, the few successful programs include those in New South Wales published by David Myers and the rearing of seven young from two pairs in a television feature on Burke's Backyard; other captive breeding is recorded in the states of Victoria and Western Australia.[4]

Two specimens held at the National Museum of Victoria were acquired from a local aviculturalist in 1941.[29]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Stagonopleura oculata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Species Stagonopleura (Zonaeginthus) oculata (Quoy & Gaimard, 1830)". biodiversity.org.au. Australian Faunal Directory.

- ↑ Jobling, J. A. (2018). Key to Scientific Names in Ornithology. In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.) (2018). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from www.hbw.com).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Forshaw, Joseph Michael; Shephard, Mark (2012). Grassfinches in Australia. CSIRO. pp. 64–75. ISBN 9780643096349.

- ↑ Alexander, W. B. (1916). "History of zoology in Western Australia". Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia. 1: 129. ISSN 0035-922X.

- 1 2 3 4 Gould, John (1865). "Sp. 250". Handbook to The birds of Australia. v.1. London: Gould. pp. 407–08.

- ↑ Jobling, J. A. "Key to Scientific Names in Ornithology". www.hbw.com. HBW Alive. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- 1 2 Cayley, Neville W. (1931). What bird is that? (1956 reprint ed.). Sydney: Angus and Robertson. p. 170.

- ↑ Cayley, Neville W. (2011). Lindsey, Terence R., ed. What bird is that?: a completely revised and updated edition of the classic Australian ornithological work (Signature ed.). Walsh Bay, N.S.W.: Australia's Heritage Publishing. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-9870701-0-4.

- ↑ Abbott, Ian (2009). "Aboriginal names of bird species in south-west Western Australia, with suggestions for their adoption into common usage" (PDF). Conservation Science Western Australia Journal. 7 (2): 213–78 [255].

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reader's digest complete book of Australian birds (2nd rev. 1st ed.). Reader's Digest Services. 1982. p. 530. ISBN 978-0909486631.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Serventy, D. L.; Whittell, H. M. (1951). A handbook of the birds of Western Australia (with the exception of the Kimberley division) (2nd ed.). Perth: Paterson Brokensha. pp. 351–52.

- ↑ "Waxbills, parrotfinches, munias, whydahs, Olive Warbler, accentors, pipits « IOC World Bird List". www.worldbirdnames.org. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- 1 2 Pizzey, Graham; Knight, Frank (2012). The field guide to the birds of Australia (Ninthition ed.). Angus and Robertson. ISBN 9780732291938.

- 1 2 3 4 5 North, Alfred J. (1901–14). Nests and eggs of birds found breeding in Australia and Tasmania. 4. Sydney: Australian Museum. p. 438.

- ↑ Morcombe, Michael (2017). Field Guide to the Birds of Western Australia. Steve Parish Publishing. ISBN 9781925243314.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Storr, G. M. (1991). Birds of the South-west Division of Western Australia (PDF). Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement no. 35. Western Australian Museum. pp. 132–33. OCLC 24474223.

- ↑ "Red-eared Firetail (Stagonopleura oculata) BirdLife species factsheet". datazone.birdlife.org. BirdLife International. 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ Garnett, S. 1993. Threatened and extinct birds of Australia. 2nd ed. (corrected). Royal Australasian Ornithologists' Union and Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service, Moonee Ponds, Australia.

- ↑ Gould, John (1848). "Pl. 79, et seq.". The birds of Australia. v.3 (1848). London: Gould.

- 1 2 Carter, Tom (1921). "on some Western Australian Birds". Ibis. 11. 3 (9): 74–5. ISSN 0019-1019.

- 1 2 Morcombe 1986, p. 241.

- 1 2 Thomas, Richard; Thomas, Sarah; Andrew, David; McBride, Alan (2011). The Complete Guide to Finding the Birds of Australia (2nd ed.). Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09785-8.

- ↑ Morcombe 1986, p. 392.

- ↑ Morcombe 1986, p. 395.

- ↑ Hall, Robert (1902). "Birds from Western Australia". Ibis. 8. 2 (5): 121–41. ISSN 0019-1019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shephard, Mark (1989). Aviculture in Australia: Keeping and Breeding Aviary Birds. Prahran, Victoria: Black Cockatoo Press. pp. 180–81. ISBN 978-0-9588106-0-9.

- ↑ Shephard, M. in Forshaw (2012) citing Dr. M. Chinner of South Australia who discovered young from birds he had caged.

- ↑ Shephard (Forshaw, 2012) cit. Myers (2009), "Victorian naturalist Ray Murray".

- Morcombe, Michael (1986). The Great Australian Birdfinder. Sydney: Lansdowne Press. ISBN 978-0-7018-1962-0.