Ventriloquism

Ventriloquism, or ventriloquy, is an act of stagecraft in which a person (a ventriloquist) changes his or her voice so that it appears that the voice is coming from elsewhere, usually a puppeteered prop, known as a "dummy". The act of ventriloquism is ventriloquizing, and the ability to do so is commonly called in English the ability to "throw" one's voice.

History

Origins

Originally, ventriloquism was a religious practice.[1] The name comes from the Latin for to speak from the stomach, i.e. venter (belly) and loqui (speak).[2] The Greeks called this gastromancy (Greek: εγγαστριμυθία). The noises produced by the stomach were thought to be the voices of the unliving, who took up residence in the stomach of the ventriloquist. The ventriloquist would then interpret the sounds, as they were thought to be able to speak to the dead, as well as foretell the future. One of the earliest recorded group of prophets to use this technique was the Pythia, the priestess at the temple of Apollo in Delphi, who acted as the conduit for the Delphic Oracle.

One of the most successful early gastromancers was Eurykles, a prophet at Athens; gastromancers came to be referred to as Euryklides in his honour.[3] In the Middle Ages, it was thought to be similar to witchcraft. As Spiritualism led to stage magic and escapology, so ventriloquism became more of a performance art as, starting around the 19th century, it shed its mystical trappings.

Other parts of the world also have a tradition of ventriloquism for ritual or religious purposes; historically there have been adepts of this practice among the Zulu, Inuit, and Māori peoples.[3]

Emergence as entertainment

The shift from ventriloquism as manifestation of spiritual forces toward ventriloquism as entertainment happened in the eighteenth century at the travelling funfairs and market towns. An early depiction of a ventriloquist dates to 1754 in England, where Sir John Parnell is depicted in the painting An Election Entertainment by William Hogarth as speaking via his hand.[4] In 1757, the Austrian Baron de Mengen performed with a small doll.[5]

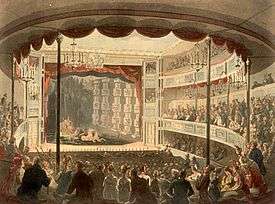

By the late 18th century, ventriloquist performances were an established form of entertainment in England, although most performers threw their voice to make it appear that it emanated from far away, rather than the modern method of using a puppet. A well known ventriloquist of the period, Joseph Askins, who performed at the Sadler's Wells Theatre in London in the 1790s advertised his act as "curious ad libitum Dialogues between himself and his invisible familiar, Little Tommy".[6] However, other performers were beginning to incorporate dolls or puppets into their performance, notably the Irishman James Burne who "... carries in his pocket, an ill-shaped doll, with a broad face, which he exhibits ... as giving utterance to his own childish jargon," and Thomas Garbutt.

The entertainment came of age during the era of the music hall in the United Kingdom and vaudeville in the United States. George Sutton began to incorporate a puppet act into his routine at Nottingham in the 1830s, but it is Fred Russell who is regarded as the father of modern ventriloquism. In 1886, he was offered a professional engagement at the Palace Theatre in London and took up his stage career permanently. His act, based on the cheeky-boy dummy "Coster Joe" that would sit in his lap and 'engage in a dialogue' with him was highly influential for the entertainment format and was adopted by the next generation of performers. (A blue plaque has been embedded in a former residence of Russell by the British Heritage Society which reads 'Fred Russell the father of ventriloquism lived here').[7]

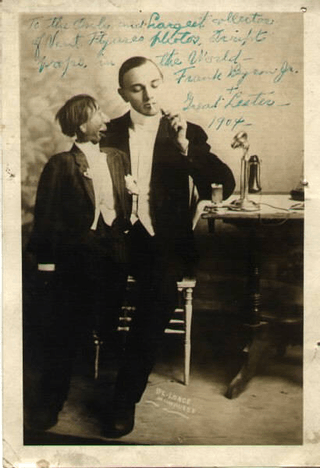

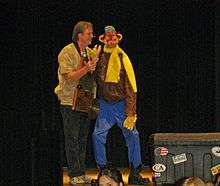

Fred Russell's successful comedy team format was applied by the next generation of ventriloquists. It was taken forward by the British Arthur Prince with his dummy Sailor Jim, who became one of the highest paid entertainers on the music hall circuit, and by the Americans The Great Lester, Frank Byron, Jr., and Edgar Bergen. Bergen popularised the idea of the comedic ventriloquist. Bergen, together with his favourite figure, Charlie McCarthy, hosted a radio program that was broadcast from 1937 to 1956. It was the #1 program on the nights it aired. Bergen continued performing until his death in 1978, and his popularity inspired many other famous ventriloquists who followed him, including Paul Winchell, Jimmy Nelson, David Strassman, Jeff Dunham, Terry Fator, Ronn Lucas, Wayland Flowers, Shari Lewis, Willie Tyler, Jay Johnson, Nina Conti, and Darci Lynne Farmer. Another ventriloquist popular in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s was Señor Wences.

The art of ventriloquism was popularised by Y. K. Padhye in North India and M. M. Roy in South India, who are believed to be the pioneers of this field in India. Y. K. Padhye's son Ramdas Padhye borrowed from him and made the art popular amongst the masses through his performance on television. Ramdas Padhye's son Satyajit Padhye is also a ventriloquist. Similarly, Indusree a female ventriloquist from Bangalore has contributed a lot to the art. She performs with 3 dummies simultaneously. Venky Monkey and Mimicry Srinivos, the disciples of M. M. Roy, popularized this art by giving shows in India and abroad. Mimicrist Srinivos, in particular, did several experiments in ventriloquism. He has popularized this art, calling it "Sound illusion." He goes into the audience without a microphone and entertains with point blank sound illusion in addition to entertaining on stage with dummies.

Ventriloquism's popularity waned for a while, probably because of modern media's electronic ability to convey the illusion of voice, the natural special effect that is the heart of ventriloquism. In the U.K. in the 2000s there were only 15 full-time professional ventriloquists, down from around 400 in the 50s and 60s.[8] A number of modern ventriloquists have developed a following as the public taste for live comedy grows. In 2007, Zillah & Totte won the first season of Sweden's Got Talent and became one of Sweden's most popular family/children entertainers. A feature-length documentary about ventriloquism, I'm No Dummy, was released in 2010.[9] Two different ventriloquists won seasons 10 and 12 of America's Got Talent. Respectively, they were Paul Zerdin on September 16, 2015, and Darci Lynne Farmer on September 20, 2017.

Making the right sounds

One difficulty ventriloquists face is that all the sounds that they make must be made with lips slightly separated. For the labial sounds f, v, b, p, and m, the only choice is to replace them with others. A widely parodied example of this difficulty is the "gottle o' gear", from the reputed inability of less skilled practitioners to pronounce "bottle of beer".[10] If variations of the sounds th, d, t, and n are spoken quickly, it can be difficult for listeners to notice a difference.

Ventriloquist's dummy

Modern ventriloquists use a variety of different types of puppets in their presentations, ranging from soft cloth or foam puppets (Verna Finly's work is a pioneering example), flexible latex puppets (such as Steve Axtell's creations) and the traditional and familiar hard-headed knee figure (Tim Selberg's mechanized carvings). The classic dummies used by ventriloquists (the technical name for which is ventriloquial figure) vary in size anywhere from twelve inches tall to human-size and larger, with the height usually falling between thirty-four and forty-two inches. Traditionally, this type of puppet has been made from papier-mâché or wood. In modern times, other materials are often employed, including fiberglass-reinforced resins, urethanes, filled (rigid) latex, and neoprene.[11]

Great names in the history of dummy making include Jeff Dunham, Frank Marshall (the Chicago creator of Bergen's Charlie McCarthy,[12] Nelson's Danny O'Day,[12] and Winchell's Jerry Mahoney), Theo Mack and Son (Mack carved Charlie McCarthy's head), Revello Petee, Kenneth Spencer, Cecil Gough,[13] and Glen & George McElroy. The McElroy brothers' figures are still considered by many ventriloquists as the apex of complex movement mechanics, with as many as fifteen facial and head movements controlled by interior finger keys and switches. Jeff Dunham referred to his McElroy figure Skinny Duggan as "the Stradivarius of dummies."

Fear of ventriloquist's dummies

Films and programs which refer to dummies that are alive and frightening include Magic,[14] Dead of Night,[14] The Twilight Zone,[14] Poltergeist, Devil Doll,[15] Dead Silence, Child's Play, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Goosebumps, Seinfeld (the episode "The Chicken Roaster"), ALF (the episode "I'm Your Puppet"), and Doctor Who in different episodes. Literary examples of frightening ventriloquist dummies include Gerald Kersh's The Horrible Dummy and the story "The Glass Eye" by John Keir Cross.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Howard, Ryan (2013). Punch and Judy in 19th Century America: A History and Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. p. 101. ISBN 0-7864-7270-7

- ↑ The Concise Oxford English Dictionary. 1984. p. 1192. ISBN 0-19-861131-5.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, 1911, Ventriloquism.

- ↑ Baldini, Gabriele, and Gabriele Mandel (1967). L'opera completa di Hogarth pittore. Milano: Rizzoli. p. 112. OCLC 958953004.

- ↑ "The Art of Improving the Voice and Ear". Book. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ↑ John A. Hodgson. "An Other Voice: Ventriloquism in the Romantic Period". Erudit.

- ↑ Davies, Helen (2012). Gender and Ventriloquism in Victorian and Neo-Victorian Fiction: Passionate Puppets. Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ BBC. Magazine. Ventriloquism: Return of the dummy run

- ↑ http://digitalcinemareport.com/node/1165#.W2u0QX7_qEI

- ↑ Burton, Maxine; et al. (2008). Improving Reading – Phonics and Fluency. National Research and Development Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy, University of London. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-906395-07-0.

Note the lip movement for 'big'. This is, of course, the origin of the ventriloquist's 'gottle o' gear'.

- ↑ "Look Inside A Dummy's Head." Popular Mechanics, December 1954, pp. 154–157.

- 1 2 "Ventriloquism LEGEND Profile: Jimmy Nelson". TalkingComedy.com.

- ↑ "Jeff Dunham - 21st Century Ventriloquist". How To Do Ventriloquism. Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Archie Andrews: The rise and fall of a ventriloquist's dummy". The Independent. London. 26 November 2005.

- ↑ Young, R. G. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film: Ali Baba to Zombies. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 155. ISBN 1-55783-269-2

References

- Vox, Valentine I Can See Your Lips Moving, the history and art of ventriloquism (1993) 224 pages. (3000 year history of the practice. Plato Publishing/Empire publications ISBN 0-88734-622-7

- Leigh Eric Schmidt (1998) "From Demon Possession to Magic Show: Ventriloquism, Religion, and the Enlightenment". Church History. 67 (2). 274-304.

- Ventriloquism, A Dissociated Perspective by Angela Mabe

- The Catholic Encyclopedia's Necromancy entry

External links

| Look up ventriloquism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ventriloquism. |