Digital obsolescence

Digital obsolescence is a situation where a digital resource is no longer readable because of its archaic format: the physical media, the reader (required to read the media), the hardware, or the software that runs on it is no longer available.[1]

A prime example of this is the BBC Domesday Project from the 1980s, although its data was eventually recovered after a significant amount of effort. Cornell University Library’s digital preservation tutorial (now hosted by ICPSR) has a timeline of obsolete media formats, called the "Chamber of Horrors", that shows how rapidly new technologies are created and cast aside.

Introduction

The rapid evolution and proliferation of different kinds of computer hardware, modes of digital encoding, operating systems and general or specialized software ensures that digital obsolescence will become a problem in the future.[2] Many versions of word-processing programs, data-storage media, standards for encoding images and films are considered "standards" for some time, but in the end are always replaced by new versions of the software or completely new hardware. Files meant to be read or edited with a certain program (for example Microsoft Word) will be unreadable in other programs, and as operating systems and hardware move on, even old versions of programs developed by the same company become impossible to use on the new platform (for instance, older versions of Microsoft Works, before Works 4.5, cannot be run under Windows 2000 or later).

Early attention was brought to the challenges of preserving machine-readable data by the work of Charles M Dollar in the 1970s, but it was only during the 1990s that libraries and archives came to appreciate the significance of the problem[3] and has been discussed among professionals in those branches, though so far without any obvious solutions other than continual forward-migration of files and information to the latest data-storage standards. File formats should be widespread, backward compatible, often upgraded, and, ideally, open format. In 2002, the National Initiative for a Networked Cultural Heritage cited[4] the following as "de facto" formats that are unlikely to be rendered obsolete in the near future: uncompressed TIFF and ASCII and RTF (for text).

In order to prevent this from happening, it is important that an institution regularly evaluate and explore its current technologies and evaluate its long term business model.[1]

Types

Digital objects are vulnerable to three types of obsolescence:[5]

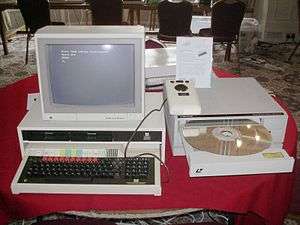

- Physical media: the physical carrier of the digital file becomes obsolete; e.g. 8 inch floppy disks, which are no longer commercially available.

- Hardware: the hardware needed to access the digital file becomes obsolete; e.g. floppy disk drive, which computers are no longer manufactured with.

- Software: the software needed to access the digital file becomes obsolete; e.g. WordStar, a word processor popular in the 1980s which used a closed data format and is no longer readily available. Another form, especially for video games, is Abandonware which is without continued support very fast obsolete and incompatible with recent systems.

Intentional obsolescence

In some cases, obsolete technologies are used in a deliberate attempt to avoid data intrusion in a strategy known as "security through obsolescence".[6]

Copyright issues as challenge

Untangling copyright issues also presented a significant challenge for projects attempting to overcome the obsolescence issues related to the BBC Domesday Project. In addition to copyright surrounding the many contributions made by the estimated 1 million people who took part in the project, there are also copyright issues that relate to the technologies employed. It is likely that the Domesday Project will not be completely free of copyright restrictions until at least 2090, unless copyright laws are revised for earlier expiration of software into public domain.[7]

Strategies

Any organization that has digital records should assess its records to identify any potential risks for file format obsolescence. The Library of Congress maintains Sustainability of Digital Formats, which includes technical details about many different format types. The UK National Archives maintains an online registry of file formats called PRONOM.

In its 2014 agenda, the National Digital Stewardship Alliance recommended developing File Format Action Plans: "it is important to shift from more abstract considerations about file format obsolescence to develop actionable strategies for monitoring and mining information about the heterogeneous digital files the organizations are managing."[8]

File Format Action Plans are documents internal to an organization which list the type of digital files in its holdings and assess what actions should be taken to ensure its ongoing accessibility.[9] Examples include the Florida Digital Archive Action Plan and University of Michigan's Deep Blue Preservation and Format Support Policy.

Responses

Open source software is often cited as solution for preventing digital obsolescence.[10][11] With the available source code the implementation and functionality is transparent and adaptions to modern not obsolete hardware platforms is always possible. Also, there is in general a strong cross-platform culture in the open source software ecosystem, which makes the systems and software more future proof.

Open standards were created to prevent digital obsolesce of file formats and hardware interfaces. For instance, PDF/A is an open standard based on Adobe Systems PDF format.[12] It has been widely adopted by governments and archives around the world, such as the United Kingdom.[13] The Open Document Format for Office Applications (OpenDocument) has been standardized by OASIS in 2005, and by ISO in 2006.

On 30 November 2017, the Digital Preservation Coalition released The 'Bit List' of Digitally Endangered Species[14] , identifying file formats at risk, as part of an international campaign to raise awareness of the need to preserve digital materials on the first International Digital Preservation Day.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Managing Digital Obsolescence Risks" (PDF). The National Archives. April 2009. Archived from the original (pdf) on 28 June 2011.

- ↑ Rothenberg, J. (1998). Avoiding Technological Quicksand: Finding a Viable Technical Foundation for Digital Preservation Archived 2007-12-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hedstrom, M. (1995). Digital Preservation: A Time Bomb for Digital Libraries Archived 2016-11-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ National Initiative for a Networked Cultural Heritage. (2002). NINCH Guide to Good Practice in the Digital Representation and Management of Cultural Heritage Materials Archived 2007-12-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Obsolescence – a key challenge in the digital age". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Miller, Robin (2002-06-06). "Security through obsolescence". Linux.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-28. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ Charlesworth, Andrew (5 November 2002). "The CAMiLEON Project: Legal issues arising from the work aiming to preserve elements of the interactive multimedia work entitled "The BBC Domesday Project."". Kingston upon Hull: Information Law and Technology Unit, University of Hull. Archived from the original (Microsoft Word) on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "National Agenda for Digital Stewardship 2014" (PDF). National Digital Stewardship Alliance. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Owens, Trevor (6 January 2014). "File Format Action Plans in Theory and Practice". Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Cassia, Fernando (March 28, 2007). "Open Source, the only weapon against 'planned obsolescence'". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ↑ Donoghue, Andrew (19 July 2007). "Defending against the digital dark age". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- ↑ "Adobe Acrobat Engineering:PDF Standards". Adobe. 12 March 2013. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ↑ "Viewing government documents". GOV.UK. Cabinet Office. 6 August 2015. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ↑ DPC (2017-11-30). "Digitally Endangered Species - Digital Preservation Coalition". dpconline.org. Retrieved 2017-11-30.