Dicamba

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

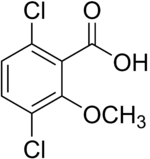

| IUPAC name

3,6-Dichloro-2-methoxybenzoic acid | |

| Other names

3,6-Dichloro-o-anisic acid Dianat | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.033 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H6Cl2O3 | |

| Molar mass | 221.03 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid |

| Density | 1.57 |

| Melting point | 114 to 116 °C (237 to 241 °F; 387 to 389 K) |

| 500 g/L | |

| Solubility in acetone | 810 g/L |

| Solubility in ethanol | 922 g/L |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 199 °C (390 °F; 472 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Dicamba (3,6-dichloro-2-methoxybenzoic acid) is a broad-spectrum herbicide first registered in 1967. Brand names for formulations of this herbicide include Banvel, Diablo, Oracle and Vanquish. This chemical compound is a chlorinated derivative of o-Anisic acid.[2]

Use as an herbicide

Dicamba controls annual and perennial rose weeds in grain crops and highlands, and it is used to control brush and bracken in pastures, as well as legumes and cacti. In combination with a phenoxy herbicide or with other herbicides, dicamba is used in pastures, range land, and noncrop areas (fence rows, roadways, and wastage) to control weeds. Dicamba is toxic to conifer species but is in general less toxic to grasses.[3]

Dicamba functions by increasing plant growth rate.[3] At sufficient concentrations, the plant outgrows its nutrient supplies and dies.[4]

The growth regulating properties of dicamba were first discovered by Zimmerman and Hitchcock in 1942. Soon after Jealott's Hill Experimental Station in England was evaluating dicamba in the field. Dicamba has since been used for household and commercial weed control.

Increasing use of dicamba has been reported with the release of dicamba-resistant genetically modified plants by Monsanto. In October 2016, the EPA launched a criminal investigation into the illegal application of older, drift prone formulations of dicamba onto these new plants.[5][6] Older formulations have been reported to drift after application and affect other crops not meant to be treated.[7][8] A less volatile formulation of dicamba made by Monsanto, designed to be less prone to vaporizing and inhibit unintended drift between fields, was approved for use in the United States by the EPA in 2016, and was expected to be commercially available in 2017.[9]

Resistance

Some weed species, like Amaranthus palmeri, have developed resistance to dicamba. Dicamba resistance in Bassia scoparia was discovered in 1994 and has not been explained by common modes of resistance such as absorption, translocation, or metabolism.[10]

Genetically modified crops

The soil bacterium Pseudomonas maltophilia (strain DI-6) converts dicamba to 3,6-dichlorosalicylic acid (3,6-DCSA), which is adsorbed to soil much more strongly than is dicamba, but lacks herbicidal activity. Little information is available on the toxicity of this breakdown intermediate. The enzymes responsible for this first breakdown step is a three-component system called dicamba O-demethylase.

Monsanto recently incorporated one component of the three enzymes into the genome of soybean, cotton, and other broadleaf crop plants, making them resistant to dicamba.[11] Monsanto has marketed their dicamba resistant crops under the brand name Xtend.[12]

Volatilization

Dicamba came under scrutiny due to its tendency to vaporize from treated fields and spread to neighboring crops.[13] Monsanto began offering crops resistant to dicamba before a reformulated and drift resistant herbicide, which they claimed would be less likely to affect neighboring fields, had gained approval from the Environmental Protection Agency. Incidents in which dicamba affected neighboring fields led to complaints from farmers and fines in some US states.[14][upper-alpha 1] A lower volatility formulation, M1768, was approved by the EPA in November 2016.[16] However, this formulation has not been evaluated by experts outside of Monsanto.[17]

Toxicological effects

Dicamba does not present unusual handling hazards.[18] It is moderately toxic by ingestion and slightly toxic by inhalation or dermal exposure (oral LD50 in rats: 757 mg/kg body weight, dermal LD50 in rats: >2,000 mg/kg, inhalation LC50 in rats: >200 mg/L).

In a three-generation study, dicamba did not affect the reproductive capacity of rats. When rabbits were given doses of 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 10, or 20 (mg/kg)/day of technical dicamba from days 6 through 18 of pregnancy, toxic effects on the mothers, slightly reduced fetal body weights, and increased loss of fetuses occurred at the 10 mg/kg dose. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set the NOAEL for this study at 3 (mg/kg)/day.

In dog tests, some enlargement of liver cells has occurred, but a similar effect has not been shown in humans.[19]

Recent studies suggest that dicamba should be considered to be a potential endocrine disruptor for fish at environmentally relevant concentrations.[20]

Environmental impact

Soil

Dicamba is released directly to the environment by its application as an herbicide for the control of annual broadleaf weeds. It may cause damage to plants as a result of its absorption from the soil by plant roots. Dicamba is mobile in most soils and significant leaching is possible. The adsorption of dicamba to organo-clay soil is influenced by soil pH with the greatest adsorption to soil occurring in acidic soils. Dicamba is moderately persistent in soil. Its reported half-life in soil ranges from 1 to 6 weeks. Dicamba is likely to be more rapidly degraded in soils with high microbial populations, but dissipates more slowly in hardwood forests and wetlands than would be expected from the results of laboratory studies.

At a level of 10 mg/kg in sandy loam soil, dicamba caused a transient decrease in nitrification after two but not three weeks of incubation. The investigator determined that the decrease in nitrification is not substantial and does not suggest the potential for a prolonged impact on microbial activity. In the same study, dicamba did not affect ammonia formation or sulfur oxidation. In a more recent laboratory study, dicamba, at a concentration of 1 mg/kg soil, did not affect urea hydrolysis or nitrification in four soil types.

Water

Dicamba salts used in some herbicides are highly soluble in water. A recent study conducted by the U.S. Geologic Survey (USGS 1998) found dicamba in 0.11%-0.15% of the ground waters surveyed. The maximum level detected was 0.0025 mg/L. The prevalence of dicamba in groundwater from agricultural areas (0.11%) did not correlate with nonagricultural urban areas (0.35%).

Dicamba was tested for acute toxicity in a variety of aquatic animals. The studies accepted by the U.S. EPA found dicamba acid and DMA salt to be practically nontoxic to aquatic invertebrates. Studies accepted by the U.S. EPA found dicamba acid to be slightly toxic to cold water fish (rainbow trout), and practically nontoxic to warm water fish.

Possible unintended consequences

Some farmers and researchers have expressed concern about herbicide resistance after the introduction of resistant crops.[12][15] In the laboratory, researchers have demonstrated weed resistance to dicamba within three generations of exposure.[12] Similar herbicide resistance weeds arose after the introduction of glyphosate-resistant crops (marketed as 'Roundup Ready').[12][15][21][22]

Farmers have also expressed concern about being forced to grow resistant crops as protection against drifting dicamba.[12]

Legality

Arkansas and Missouri banned the sale and use of dicamba in July 2017 in response to complaints of crop damage due to drift.[23] Monsanto responded by arguing that not all instances of crop damage had been investigated and a ban was premature.[24] Monsanto also sued the state of Arkansas to stop the ban, and that lawsuit was dismissed in February 2018.[25]

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 3026.

- ↑ dicamba (Banvel) Herbicide Profile 10/83, Pesticide Management Education Program, Cornell University|http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/herb-growthreg/dalapon-ethephon/dicamba/herb-prof-dicamba.html

- 1 2 Arnold P. Appleby, Franz Müller. "Weed Control, 2" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2011, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.o28_o01

- ↑ http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/nr/fid/pubsweb/dicamba_99.pdf Retrieved 20 May 2010

- ↑ Weinraub, Mark (25 October 2016). "U.S. agency searches for proof of criminal use of herbicide dicamba". Reuters. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ "EPA Probes Dicamba Use- Federal Search Warrants Issued in Missouri". KTIC Radio. 25 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ↑ Gray, Bryce (5 August 2016). "Suspected illegal herbicide use takes toll on southeast Missouri farmers". St Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Gray, Bryce (14 August 2016). "Illegal herbicide use may threaten survival of Missouri's largest peach farm". St Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Gray, Bryce (9 November 2016). "EPA approves Monsanto's less-volatile form of dicamba herbicide". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Cranston, Harwood J.; Kern, Anthony J.; Hackett, Josette L.; Miller, Erica K.; Maxwell, Bruce D.; Dyer, William E. (2001). "Dicamba resistance in kochia". Weed Science. 49 (2): 164. doi:10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049[0164:DRIK]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Behrens, M. R.; Mutlu, N.; Chakraborty, S.; Dumitru, R.; Jiang, W. Z.; Lavallee, B. J.; Herman, P. L.; Clemente, T. E.; Weeks, D. P. (2007). "Dicamba Resistance: Enlarging and Preserving Biotechnology-Based Weed Management Strategies". Science. 316 (5828): 1185–8. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1185B. doi:10.1126/science.1141596. PMID 17525337.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Charles, Dan (1 August 2016). "Crime In The Fields: How Monsanto And Scofflaw Farmers Hurt Soybeans In Arkansas". NPR. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (25 April 2012). "Dow Corn, Resistant to a Weed Killer, Runs Into Opposition". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ Tatge, Jason (9 November 2017). "Protecting Your Business with Ag Data: What Dicamba Can Teach Us (Guest Column) | PrecisionAg". PrecisionAg. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Business: Monsanto's Superweeds Saga Is Only Getting Worse". Yahoo, TakePart.com. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ↑ Final Registration of Dicamba on Dicamba-Tolerant Cotton and Soybean, 9 November 2016

- ↑ "Scant oversight, corporate secrecy preceded U.S. weed killer crisis". 9 August 2017 – via Reuters.

- ↑ dicamba (Banvel) Herbicide Profile 10/83 Retrieved 20 May 2010

- ↑ Pesticide Information Profile – Dicamba, Pesticide Management Education Program, Cornell University.

- ↑ Zhu, L; Li, W; Zha, J; Wang, Z (2015). "Dicamba affects sex steroid hormone level and mRNA expression of related genes in adult rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) at environmentally relevant concentrations". Environmental toxicology. 30 (6): 693–703. doi:10.1002/tox.21947. PMID 24420721.

- ↑ http://www.scientificamerican.com/media/inline/a-hard-look-at-3-myths-about-genetically-modified-crops_3.jpg

- ↑ Dewey, Caitlin (29 August 2017). "This miracle weed killer was supposed to save farms. Instead, it's devastating them". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Gray, Bryce (7 July 2017). "Missouri and Arkansas ban dicamba herbicide as complaints snowball". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Pucci, Jackie (10 July 2017). "Monsanto Responds to Arkansas, Missouri Dicamba Bans". Crop Life. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Nosowitz, Dan. "Monsanto's Lawsuit Against Arkansas for Dicamba Ban Dismissed". Modern Farmer. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

External links

- Appendix E: Herbicide Information, US Department of Agriculture

- Chemical Fact Sheet, Speclab.com

- Dicamba Technical Fact Sheet – National Pesticide Information Center

- Dicamba General Fact Sheet – National Pesticide Information Center

- Dicamba Pesticide Information Profile – Extension Toxicology Network

- Monsanto's Xtend Crop System Product Page

- EPA Dicamba Reregistration Eligibility Decision