Deadweight loss

A deadweight loss, also known as excess burden or allocative inefficiency, is a loss of economic efficiency that can occur when equilibrium for a good or a service is not achieved. That can be caused by monopoly pricing in the case of artificial scarcity, an externality, a tax or subsidy, or a binding price ceiling or price floor such as a minimum wage.

Examples

An example is a market for nails where the cost of each nail is $0.10 and the demand decreases linearly, from a high demand for free nails to zero demand for nails at $1.10. If the market has perfect competition, producers would have to charge a price of $0.10, and every customer whose marginal benefit exceeds $0.10 would have a nail. However, if there is one producer with a monopoly on the product, it will charge whatever price will yield the greatest profit. The producer would then charge $0.60 and thus exclude every customer who had less than $0.60 of marginal benefit. The deadweight loss would then be the economic benefit foregone by such customers because of monopoly pricing.

Conversely, deadweight loss can come from consumers if they buy a product even if it costs more than it benefits them. To describe this, if the same nail market had the government giving a $0.03 subsidy to every nail produced, the subsidy would push the market price of each nail down to $0.07. Some consumers would then buy nails even though the benefit to them is less than the real cost of $0.10. That unneeded expense would then create a deadweight loss, with resources not being used efficiently.

If the price of a glass of wine is $3.00 and the price of a glass of beer is $3.00, a consumer might prefer to drink wine. If the government decides to levy a wine tax of $3.00 per glass, the consumer might prefer to drink beer. The excess burden of taxation is the loss of utility to the consumer for drinking beer instead of wine since everything else remains unchanged.

Harberger's triangle

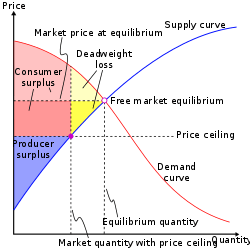

Harberger's triangle, generally attributed to Arnold Harberger, refers to the deadweight loss (as measured on a supply and demand graph) associated with government intervention in a perfect market. That can happen through price floors, caps, taxes, tariffs, or quotas. It also refers to the deadweight loss created by a government's failure to intervene in a market with externalities.[1] In the case of a government tax, the amount of the tax drives a wedge between what consumers pay and what producers receive, and the filled-in wedge shape is equivalent to the deadweight loss from the tax.[2]

The area represented by the triangle comes from the fact that the intersection of the supply and the demand curves are cut short so the consumer surplus and the producer surplus are also cut short. The loss of such surplus that is not recouped, is the deadweight loss.

Some economists like James Tobin have argued that the triangles do not have a huge impact on the economy, but others like Martin Feldstein maintain that they can seriously affect long-term economic trends by pivoting the trend downwards and cause a magnification of losses in the long run.

Hicks vs. Marshall

An important distinction should be made between Hicksian (per John Hicks) and Marshallian (per Alfred Marshall) deadweight loss. After the consumer surplus is considered, it can be shown that the Marshallian deadweight loss is zero if demand is perfectly elastic or supply is perfectly inelastic. However, Hicks analyzed the situation through indifference curves and noted that when the Marshallian demand curve is perfectly inelastic, the policy or economic situation that caused a distortion in relative prices has a substitution effect, i.e. is a deadweight loss.

In modern economic literature, the most common measure of a taxpayer’s loss from a distortionary tax, such as a tax on bicycles, is the equivalent variation, the maximum amount that a taxpayer would be willing to forgo in a lump sum to avoid the distortionary tax. The deadweight loss can then be interpreted as the difference between the equivalent variation and the revenue raised by the tax. The difference is attributable to the behavioural changes induced by a distortionary tax that are measured by a substitution effect. However, that is not the only interpretation, and Lind and Granqvist (2010) point out that Pigou did not use a lump sum tax as the point of reference to discuss deadweight loss (excess burden).

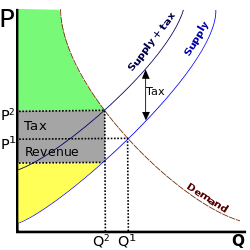

Deadweight loss of Taxation

When a tax is levied on buyers, the demand curve shifts downward by the size of the tax. Similarly, when tax is levied on sellers, the supply curve shifts upward by the size of tax. When the tax is imposed, the price paid by buyers increases, and the price received by seller decreases. Therefore, buyers and sellers share the burden of the tax, regardless of how it is imposed. Since tax situates a wedge between the price buyers pay and the price sellers get, the quantity sold goes down below the level that it would be without tax. To put it another way, a tax on good leads the size of market for the good to decrease. The reason is why tax creates deadweight losses can be explained with one example. Suppose that Will is a cleaner who is working in the cleaning service company and Amie hired Will to clean her room every week for $100. The opportunity cost of Will’s time is $80, while the value of a clean house to Amie is $120. Hence, each of them get same amount of benefit from their deal.Amie and Will get 20$ making the total surplus $40 from trade. However, when the government decides to imposed $50 a tax upon the providers of cleaning services. There would be no beneficial trade between them. Because Amie would not willing to pay any price above $120, while Will would not desire get his opportunity cost below the level that they have made a deal. Because of these reasons, not only Amie and Will give up the deal, but also Amie has to live dirtier house, and Will does not get his income. Thereby, they have lost amount of surplus that they have gotten from their deal, and at the same time, this made each of them worse off up to $40. When it comes to government revenue from this tax, since Amie and Will have given up the deal, the government also can not get any revenue from them. So this $40 is referred deadweight loss; it causes losses both for buyers and sellers in a market and government revenues. Taxes cause deadweight losses because they prevent buyers and sellers from realizing some of the gains from trade.[3]

In the graph, the deadweight loss can be seen at the area between the supply and demand curves. While the demand curve shows the value of goods to the consumers, the cost of the producers is reflected by supply curve. As the example above explains it, when the government imposes a tax upon taxpayers, the tax increases the price paid by buyers to Pc and decreases price received by sellers to Pp, buyers and sellers (Amie and Will) give up the deal between them and they leave the market. Thus, the quantity sold reduces from Qe to Qt. Mainly, the deadweight loss occurs because the tax deters these kinds of beneficial trades in the market.[3]

The Determinants of Deadweight losses

Price elasticities of supply and demand determines whether the deadweight loss from tax is a large or small. This basically measures how much quantity supplied and quantity demanded respond to changes in the price. For instance, when the supply curve is relatively inelastic, quantity supplied responds slightly to changes in the price. However, when the supply curve is more elastic, quantity supplied responds significantly to changes in the price. In other words, when the supply curve is more elastic, the area between the supply and demand curves is larger. Similarly, when the demand curve is relatively inelastic, deadweight loss from the tax is smaller, comparing to more elastic demand curve.

The reason is that tax has a deadweight loss, because it causes buyers and sellers to change their behaviour. Buyers tend to consume less, when the tax raises the price paid by buyers. Also, when the tax lowers the price received by sellers, they produce less. Due to these reasons, the size of market decreases below the optimum. The elasticities of supply and demand designate to what extent the tax distorts the market outcome. Thereby, as the elasticities of supply and demand increase, it causes more the deadweight loss of a tax.[3]

How Deadweight loss changes as taxes vary

Taxes have a potential to be changed over time by the government or policymakers at the different level of the state. For instance, when the small tax is levied, the deadweight loss is substantially small if we compare to medium or large tax. The deadweight loss of a tax increases more quickly than the size of the tax. Because an area of the triangle of deadweight loss based on the square of its dimension. When the size of tax is doubled, the bottom and height of the triangle double. Thus, deadweight loss increases by the number of 4. While deadweight loss occur as taxes vary, at the same time, this affects the government’s tax revenue. Tax revenue is shown as the area of the rectangle between supply and demand curve. When small tax is levied, tax revenue is relatively small. As the size of tax increases, tax revenue expands. But when the much larger tax is levied, tax revenue decreases because the larger tax lowers the size of the market. The main reason is that people would most likely stop buying and selling good in the market.[3]

Deadweight loss of a monopoly

The deadweight loss occurs in monopolies in the same way that the tax causes deadweight loss.When a monopoly, as a tax collector, charges a price in order to consolidate its power above marginal cost.it situates a wedge.As imposing a tax distorts market outcome, the wedge leads to quantity sold to go down below the social optimum. However, there is only a difference between two cases; while private company receives the monopoly profit, the government obtains the revenue from a tax.[3]

See also

References

Further reading

- Case, Karl E.; Fair, Ray C. (1999). Principles of Economics (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-961905-4.

- Hines, James R., Jr. (1999). "Three Sides of Harberger Triangles". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 13 (2): 167–188. doi:10.1257/jep.13.2.167. .

- Lind, H.; Granqvist, R. (2010). "A Note on the Concept of Excess Burden". Economic Analysis and Policy. 40 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1016/S0313-5926(10)50004-3.