Cytolysis

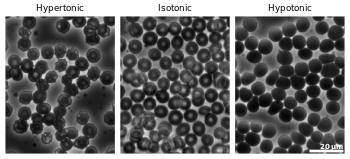

Cytolysis, or osmotic lysis, occurs when a cell bursts due to an osmotic imbalance that has caused excess water to diffuse into the cell. Water can enter the cell by diffusion through the cell membrane or through selective membrane channels called aquaporins, which greatly facilitate the flow of water.[1] It occurs in a hypotonic environment, where water moves into the cell by osmosis and causes its volume to increase to the point where the volume exceeds the membrane's capacity and the cell bursts. The presence of a cell wall prevents the membrane from bursting, so cytolysis only occurs in animal and protozoa cells which do not have cell walls. The reverse process is plasmolysis.

In mammals

Osmotic lysis is often one result of a stroke, because of improper nutrient perfusion and waste removal alter cell metabolism. Such malfunction results in an inflow of extracellular fluid into the cells.

In bacteria

Osmotic lysis would be expected to occur when bacterial cells are treated with a hypotonic solution with added lysozyme, which destroys the bacteria's cell walls.

Prevention

Different cells and organisms have adapted different ways of preventing cytolysis from occurring. For example, the paramecium uses a contractile vacuole, which rapidly pumps out excessive water to prevent the build-up of water and the otherwise subsequent lysis.[2] Additionally, these protists have cell membranes which are less permeable to water than some other species.[2]

Other organisms pump solutes out of their cytosol, which brings the solute concentration closer to that of their environment. This slows down the process of water's diffusion into the cell, preventing cytolysis. If the cell can pump out enough solutes so that an isotonic environment can be achieved, there will be no net movement of water.

See also

References

- ↑ Alberts, Bruce (2014). Essential Cell Biology (4th ed.). New York, NY: Garland Science. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-8153-4454-4.

- 1 2 Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B.; Urry, Lisa A.; Cain, Michael L.; Wasserman, Steven A.; Minorsky, Peter V.; Jackson, Robert B. (2009). Biology (9th ed.). p. 134. ISBN 9780321558237.

- McClendon, Jesse Francis (1917). Physical Chemistry of Vital Phenomena:. Original from the University of California: Princeton University Press. p. 240 pages.