Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall

| Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall | |

|---|---|

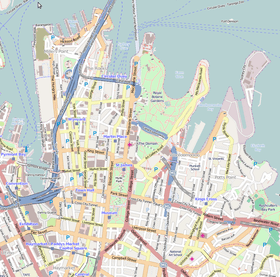

Location of Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall in Sydney | |

| Location | 150-152 Elizabeth Street, Sydney CBD, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′40″S 151°12′35″E / 33.8779°S 151.2098°ECoordinates: 33°52′40″S 151°12′35″E / 33.8779°S 151.2098°E |

| Official name: Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall | |

| Type | Listed place (Indigenous) |

| Designated | 20 May 2008 |

| Reference no. | 105937 |

Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall is a heritage-listed community building at 150-152 Elizabeth Street, Sydney CBD, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It was the site of the Day of Mourning protests by Aboriginal Australians on 26 January 1938. It was added to the Australian National Heritage List on 20 May 2008.[1]

History

History of the Day of Mourning

Since European settlement, Indigenous people have been treated differently to the general Australian population; denied the basic concession of equality with whites and rarely given full protection before the law.[2] Indigenous people have long resisted and protested against European settlement of their country.[3] Early protests were initiated by residents of missions and reserves as a result of local issues and took the form of letters, petitions and appeals.[4][1]

One of the earliest examples of this form of protest was during the mid 1840s at the Aboriginal reserve called Wybalenna on Flinders Island. Residents of Wybalenna sent letters and petitions to Queen Victoria and the Colonial Secretary and other Government officials, protesting against the living conditions and administration of Wybalenna.[5] Similarly in the mid 1870s residents of Coranderrk in Victoria began a decade long protest against the management and closure of the reserve using letters to the editors of daily newspapers and government ministers as well as seeking support from humanitarian organisations.[6][1]

This pattern of protests focusing on local concerns continued during the 1880s and 1890s with residents of Cummeragunja in New South Wales and Poonindie in South Australia also using letters and petitions to lobby for the allocation of parcels of land within the reserve to families so that they would be responsible for farming their allocated parcel.[7][1]

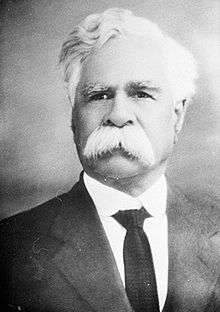

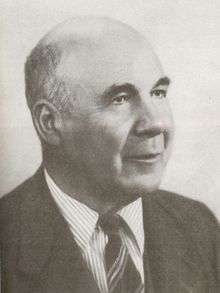

A new dynamic began in the late 1920s with the creation of regional and state based Aboriginal controlled organisations. The first of these was the short lived Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA), founded on the mid north coast of New South Wales (NSW) by Fred Maynard.[8] Subsequent state based organisations were formed in NSW with the Aboriginal Progressive Association (APA) and in Victoria with the Aboriginal Advancement League (AAL). Key founders of these organisations included William Cooper, Doug Nicholls, Margaret Tucker, William Ferguson, Jack Patten and Pearl Gibbs.[1]

The key members of both these organisations shared common life experiences; they grew up on missions or reserves controlled by protection boards but were either expelled on disciplinary grounds or left to find work.[9] The majority of these people had at one time resided at Cummeragunja and/or Warrangesda missions in NSW and a number also had lived at Salt Pan Creek, an Aboriginal squatter's camp south-west of Sydney. This camp housed refugee families, the dispossessed and people seeking to escape the harsh and brutal policies of the Aborigines Protection Board.[10] It became a focal point for intensifying Aboriginal resistance in NSW.[1]

While living off an Aboriginal reserve provided some level of freedom, these Aboriginal people experienced the full force of laws that impacted on the ability of Indigenous people to find employment, receive equal wages, seek unemployment relief and the ability to purchase or own property. The experience of living under the control of a protection board on a mission or reserve, and the barriers they faced off these reserves, united the members of these early Aboriginal organisations in their concerns for the lack of civil rights, the growth in the Aboriginal Protection Board's powers and the condition of people remaining in missions and reserves.[11][1]

It was in this environment that in November 1937 William Cooper called a meeting of the AAL in Melbourne which William Ferguson from the APA also attended.[12] During this meeting the two groups agreed to hold a protest conference in Sydney to coincide with sesquicentenary celebrations planned for Australia Day 26 January 1938. They decided to call this protest the Day of Mourning.[13][14][1]

The AAL and APA widely promoted the Day of Mourning through radio interviews and other media. To encourage Aboriginal people to attend, Jack Patten and William Ferguson took turns in touring the reserves to promote it.[15] Jack Patten and William Ferguson also published a 12 page pamphlet entitled "Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights" to promote the purpose of the Day of Mourning amongst non-Indigenous people. This "manifesto" as been described as perhaps the most bitter of Aboriginal protests.[16] It explained the significance of the action:[1]

"The 26th January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia's Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years' so-called 'progress' in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country. We, representing the Aborigines, now ask you, the reader of this appeal, to pause in the midst of your sesqui-centenary rejoicings and ask yourself honestly whether your "conscience" is clear in regard to the treatment of the Australian blacks by the Australian whites during the period of 150 years' history which you celebrate?"[17]

The pamphlet asked the reader to acknowledge the impact of the "protection" approach, the restrictions that it continued to place on Aboriginal people's rights, and to be proud of the Australian Aborigines and not misled by the superstition that they are a naturally backward and low race.[1] It also made explicit that the choice of holding the Day of Mourning on Australia Day, the national holiday celebrating the arrival of the First Fleet and the birth of Australia as a nation, was to highlight the exclusion of Aboriginal people from the Australian nation:[1]

"We ask you white Australians for justice, fair play and decency, and we speak for 80,000 human beings in your midst. We ask—and we have every right to demand—that you should include us, fully and equally with yourselves, in the body of the Australian nation".[17]

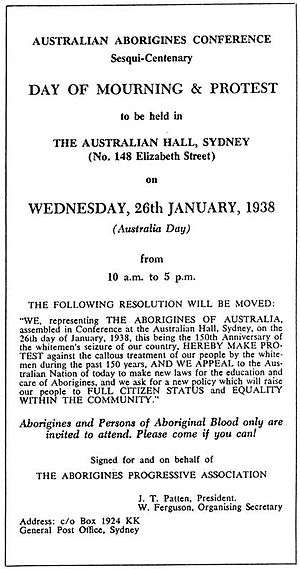

The organisers distributed approximately 2,000 leaflets and posters advertising the Day of Mourning which advised that "Aborigines and persons of Aboriginal blood only are invited to attend". The organisers were denied permission to hold the Day of Mourning in Sydney Town Hall, but were able to rent the Australia Hall at 150-152 Elizabeth Street. The use of Australia Hall was granted on condition that the delegates watched the sesquicentennial parade from the Town Hall steps and then marched behind the parade to the Australia Hall.[18][1]

.jpg)

The official Australia Day celebrations included a re-enactment of the arrival of Governor Phillip by boat at Port Jackson "who will put the Aborigines to flight".[19] The Government had brought in Aboriginal people from the Menindee reserve to participate in the re-enactment of the arrival of Governor Phillip at Port Jackson as this was a safer option then using Aboriginal people from the Sydney area.[20] These people were housed at the Redfern Police Barracks and were not allowed any contact with "disruptive influences" before the re-enactment.[21][1]

While delegates did not watch the re-enactment, they were required to watch a pageant at the Sydney Town Hall. After watching this pageant, delegates for the Day of Mourning walked to Australia Hall. Two police officers guarded the front door of the building. The Day of Mourning was held at a time when there were restrictions on Aboriginal people's rights of movement and assembly and the delegates from reserves risked imprisonment, expulsion from their homes and loss of their jobs for participating in an event such as this.[22] As a result some entered through the back door of the building to avoid identification and reprisals.[23][1]

.jpg)

Over 100 people attended the Day of Mourning from throughout NSW, Victoria and Queensland.[24] Telegrams of support for this action also came from Western Australia, Queensland and north Australia, which the organisers believed gave the gathering the status and strength of a national action.[25][1]

After a number of statements by participants, they unanimously endorsed a resolution demanding full citizen rights:[1]

"WE, representing THE ABORIGINES OF AUSTRALIA, assembled in conference at the Australian Hall, Sydney, on the 26th day of January 1938, this being the 150th Anniversary of the Whiteman's seizure of our country, HEREBY MAKE PROTEST against the callous treatment of our people by the whitemen during the past 150 years, AND WE APPEAL to the Australian nation of today to make new laws for the education and care of Aborigines, and we ask for a new policy which will raise our people to FULL CITIZEN STATUS and EQUALITY WITHIN THE COMMUNITY".

On 31 January 1938, a delegation presented this resolution, and a ten-point policy statement developed at the Day of Mourning, to the Prime Minister and the Minister for the Interior. Participants described the ten-point policy statement as the only policy which has the support of the Aborigines themselves.[25] It included a long range policy with recommendations for: Australian Government control of all Aboriginal affairs; the development of a national policy for Aborigines; the appointment of a Commonwealth Minister for Aboriginal Affairs whose aim would be to raise all Aborigines throughout Australian to full citizen status and civil equality with the whites in Australia. The latter included entitlement to: the same educational opportunities; the benefits of labor legislation, including Arbitration Court Awards, workers' compensation and insurance; receiving wages in cash, and not by orders, issue of rations, or apprenticeship systems; old-age and invalid pensions; to own land and property, and to be allowed to save money in personal banking accounts.[1]

The long range policy also identified the need for Aboriginal land settlements including tuition in areas of agriculture and financial assistance to generate self-supporting Aboriginal farmers. While opposing a policy of segregation, it advocated the retention of Aboriginal Reserves as a sanctuary for some Aboriginal people.[1]

A full report of the Day of Mourning appeared in the first issue of the monthly Australian Abo Call, the first newspaper published by Aboriginal people to voice their views.[26] It stated:[1]

"The Day of Mourning protest conference on 26 January 1938 at the Australia Hall marks the first occasion in Australian history that Aboriginal people from different states joined together to campaign for equality and full citizenship rights. Initiated and organised by key figures in two of the early Aboriginal political protest organisations, the Australian Aborigines League and the Aborigines Progressive Association, delegates joined to discuss civil rights and debate a ten-point list of demands aimed at redressing the political and legal disadvantages of Aboriginal people".[27]

Although it brought about little change in the years immediately following 1938, the Day of Mourning produced a comprehensive collection of key policies that identified impacts on the lives of Aboriginal people at the time and recommendations for how they should be addressed. One of the issues highlighted in these policies, namely Australian Government control of all Aboriginal affairs, formed the basis for the constitutional amendments endorsed by the Australian people in the Referendum of the 27th of May, 1967.[28] While there has been progress, governments still identify the broad issues raised in these documents as priority areas within Indigenous Affairs (see Ministerial Taskforce on Indigenous Affairs long term vision in Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination 2004; issues identified in Bilateral Agreements between Commonwealth and States/Territories at www.oipc.gov.au/publications/default.asp).[1]

A number of contemporary Indigenous leaders also recognise that the key policy issues identified at the Day of Mourning remain relevant to Indigenous people today. In a speech at the Australian Reconciliation Convention, Noel Pearson (1997) noted that after reading the documents associated with the Day of Mourning he "was struck either how sophisticated the movement was back then, or how far we have not come" because the issues raised in the material from the Day of Mourning remained fresh propositions. In an article published in a number of metropolitan newspapers on Australia Day in 1998, Gatjil Djerrkura noted that while advances have been made in relation to Indigenous affairs since the Day of Mourning, many of the underlying issues remain, including improvements to the health and economic opportunities in communities.[29][1]

The call at the Day of Mourning for recognition of "full citizen status" and "equality within the community" still recurs in the numerous government reports including those of the Human Rights Commission, the Social Justice Commissioner, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commissions and the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, as well as the Indigenous statements such as the Yirrkala Bark Petition, the Barunga Statement, the Eva Valley Statement and the Boomanulla Oval Statement.[30][1]

The Day of Mourning not only produced political statements that remain current, it also highlighted the exclusion of Indigenous people from the Australian nation. The ambiguous relationship between Indigenous people and the Australian nation remains an issue for Indigenous people.[31] As a result, Indigenous people have continued to use Australia Day and other foundation anniversaries to draw attention to their exclusion from the national consciousness: in 1970 a second Day of Mourning was held to demonstrate against Sydney's bicentenary celebrations of Captain Cook's "discovery" of Australia; Australia Day in 1972 saw the establishment of an Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the lawns of the then Parliament House in Canberra (now Old Parliament House) in a call for national land rights, sovereignty and self-determination; and the anti-bicentenary protests on Australia Day in 1988 is still one of the largest Indigenous protest marches in Australia.[32][1]

In the 1930s demanding the same rights as white Australians, when Indigenous people were subject to severe restrictions and punitive sanctions, constituted a radical claim in Australia and challenged the premise of the dominant racial order.[33] The Day of Mourning is therefore regarded as one of the most important moments in the history of the Indigenous resistance in the early 20th Century.[34][1]

History of Australia Hall

The building that houses Australia Hall was erected in 1910-13 for the Concordia German Club. It was purchased in 1920 by the Knights of the Southern Cross, a Catholic fraternal lay group linked with the Catholic Right, in 1922 the name of the hall in the building was changed from Miss Bishop's Hall to Australia Hall.[35] The Knights of the Southern Cross sold the building in 1979 to the Hellenic Club and it was then used by Greek Cypriots as the Cyprus Hellene Club. In 1961 Australia Hall was renovated and altered to house the Phillip (Street) Theatre and in 1989 Australia Hall became the home of the Mandolin Cinema.[36][1]

In the early 1990s the owner of the Cyprus Hellene Club planned to demolish most of the building and erect a 34-storey residential development. This proposal started a campaign by Indigenous people and the National Aboriginal History and Heritage Council to protect the building and gain recognition of the significance of the building to Indigenous people for its association with the Day of Mourning.[37] After several years of inquiries and objections, the NSW Minister for Urban Affairs and Planning made a Permanent Conservation Order over parts of the building. In 1998 the Indigenous Land Corporation, a Commonwealth statutory authority, purchased the building on behalf of the Metropolitan Aboriginal Association Inc, who now manages the building.[1]

Description

Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall is at 150-152 Elizabeth Street, Sydney.[1]

The Cyprus Hellene Club, the building which houses Australia Hall, is a three-storey masonry building in the Federation Romanesque style with the use of rusticated stone dressings. The building originally formed part of a Federation period streetscape group known as the Elizabeth Street Precinct.[38] The entire building, although internally altered over the years, remains substantially intact. The symmetrical facade to Elizabeth Street has bold modelling and textures, due to its semi-circular arches, segmental oriel windows and rock faced stonework.[1]

The former Australia Hall occupies the rear of the first floor; its interior and that of the entrance lobby and foyer both retain original Classical decorative elements possibly dating from the 1920s.[39] The front entrance and back door survive intact.[1]

Condition

The building is in a good condition. Modifications to the interior of the building have not affected its heritage significance in connection to the Day of Mourning. The front of the ground floor has undergone modernisation and has a suspended awning.[1]

Heritage listing

Since European settlement, Indigenous people have been treated differently to the general Australian population; denied the basic concession of equality and rarely given full protection before the law.[2] While Indigenous groups have long resisted and protested against this inequality, up until the 1920s these protests were generally focused on local issues.[1]

Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall was listed on the Australian National Heritage List on 20 May 2008 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

Criterion A: Events, Processes

Coinciding with the 1938 sesquicentenary celebrations for Australia Day, members of the Aboriginal Advancement League and the Aboriginal Progressive Association held the first national Indigenous protest, the Day of Mourning, to highlight that the "150 years" so-called "progress" in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country'.[17] The Day of Mourning identified a significant collection of policy issues impacting on Indigenous people and proposed recommendations for addressing these issues through government action. While there has been some progress, generally the political statements and social issues identified from the Day of Mourning are still relevant to Indigenous people today.[40] Australia Hall, as the site of the Day of Mourning, is outstanding in the course of Australia's cultural history as the first national Indigenous protest which identified issues of continuing relevance to Indigenous people.[1]

The ambiguous relationship between Indigenous people and the Australian nation remains an issue for Indigenous people.[31] The choice of holding the Day of Mourning on Australia Day, the national holiday celebrating the arrival of the first fleet and the birth of Australia as a nation, highlighted the exclusion of Aboriginal people from the Australian nation.[25] Since the Day of Mourning in 1938, Indigenous people have continued to use Australia Day celebrations to draw attention to their exclusion from the national consciousness as shown by the 1988 bicentenary protest, one of the largest Indigenous protests in Australia. Australia Hall, as the site of the Day of Mourning, is outstanding in the course of Australia's cultural history for its association with the first national Indigenous protest seeking the inclusion of Indigenous people in the Australian nation.[1]

Criterion G: Social value

The Day of Mourning played a significant role in the history of Indigenous peoples' struggle for the recognition of their civic rights and is regarded by Indigenous people as one of the most important moments in the history of the Indigenous resistance in the early 20th Century.[41] The strong social and cultural association Indigenous people have with Australia Hall and the Day of Mourning is demonstrated by the continuous references made by Indigenous leaders from across Australia to this event.[42] It is also shown through the campaign during the 1990s for the recognition of the significance of the building to Indigenous people and the depiction of the Day of Mourning at Reconciliation Place. Indigenous people have a strong association with Australia Hall, the site of the Day of Mourning, as the first national Indigenous protest which identified social justice issues of continuing relevance to Indigenous people.[1]

Criterion H: Significant people

Over 100 people Aboriginal people attended the Day of Mourning at Australia Hall. Indigenous people involved in the inception and organisation included prominent Aboriginal leaders of the time such as William Cooper, William Ferguson, Jack Patten, Pearl Gibbs, Margaret Tucker and Doug Nicholls. Their combined work produced a significant collection of policy issues impacting on Indigenous people and proposed recommendations for addressing these issues through government action. The political statements associated with the Day of Mourning are still relevant to Indigenous people today.[40] Australia Hall has a special association with the work of the organisers of the Day of Mourning, which is outstanding for its continued relevance to Indigenous people.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 "Cyprus Hellene Club - Australian Hall (Place ID 105937)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- 1 2 Bennett 1989:3

- ↑ Foley 2001

- ↑ Attwood et al 1999:9-11

- ↑ Attwood et al 1999:30

- ↑ Attwood et al 1999:31-33

- ↑ Attwood 1999:33-35

- ↑ Attwood et al 1999:58

- ↑ Attwood 2003:40

- ↑ Reason in Revolt Project 2007

- ↑ Attwood 2003:41

- ↑ Jumbunna Centre for Australian, Indigenous Studies, Education and Research 1994:6

- ↑ Horton, 1994:75

- ↑ Jumbunna Centre for Australian, Indigenous Studies, Education and Research 1994:6

- ↑ Jumbunna Centre for Australian, Indigenous Studies, Education and Research 1994:7

- ↑ Rowley (1972:79)

- 1 2 3 Patten et al 1938

- ↑ NSW Heritage Office 2000:9; Mesnage 1998

- ↑ Horner 1980:44

- ↑ Parbury 1986:107; Dodson 2000

- ↑ Dodson 2000

- ↑ Jumbunna Centre for Australian, Indigenous Studies, Education and Research 1994:4; Mesnage 1998; Burgess 2002:20

- ↑ NSW Heritage Office 2000:9

- ↑ Horner 1980:49; NSW Heritage Office 2000: 9

- 1 2 3 Patten 1938

- ↑ Goodall 1996:243; NSW Heritage Office 2000:9

- ↑ Patten, 1938

- ↑ Mesnage 1998, NSW Heritage Office 2000:9

- ↑ Djerrkura 1998

- ↑ Patrick Dodson (2000)

- 1 2 Dodson 2000; Pearson 2007

- ↑ Attwood 2003:334-336; Horton 1994:1062, 74

- ↑ Attwood 2003:66

- ↑ Foley, 2005

- ↑ Commissioners of Inquiry for Environment and Planning 1995:12

- ↑ Commissioners of Inquiry for Environment and Planning 1995:13

- ↑ Mesnage 1998

- ↑ Commissioners of Inquiry for Environment and Planning 1995:5

- ↑ Foys 1935

- 1 2 Pearson 1997; Djerrkura 1998; Dodson 2000

- ↑ Martin 1996, Foley 2005

- ↑ Pearson 1997; Djerrkura 1998; Dodson 2000; Foley 2005

Bibliography

- Attwood, B. 2003, Rights for Aborigines, Allen and Unwin: Australia.

- Attwood, B. and A. Markus. 1999, The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights: A Documentary History, Allen and Unwin: Australia.

- Attwood, B. and A. Markus. 2004, Thinking Black: William Cooper and the Australian Aboriginies League, Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra.

- Behrendt, L. (nd) The Urban Aboriginal Landscape, accessed at www.uws.edu.au/download.php?file_id=18507&filename=Behrendt_Final.pdf&mimetype=application/pdf. on 10 September 2007.

- Beazley, K, 1997, untitled paper presented to the opening ceremony of the Australian Reconciliation Convention 1997: Melbourne.

- Bennett, S. 1989, Aborigines and Political Power. Allen & Unwin: Sydney

- Burgess, C. 2002, Protests. McGraw-Hill Australia: Roseville, N.S.W.

- Council for Australian Reconciliation 1995, Going Forward, Social Justice for the first Australians, Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra

- Cultural Heritage Centre for Asia and the Pacific, Deakin University (CHCAP) 2004, Creating an Australian Democracy, Report Prepared for the Department of Environment and Heritage: Canberra.

- Dodson P. 2000, Beyond the Mourning Gate —Dealing with Unfinished Business Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies: Canberra.

- Djerrkura, G. 1998 60 Years On, Another 10 Point Plan accessed at http://www.teachingheritage.nsw.edu.au/c_building/wc2_60yearson.html on 10 September 2007.

- Goodall, H. 1996, Invasion to Embassy: land in Aboriginal politics in New South Wales, 1770-1972, Allen & Unwin in association with Black Books: St. Leonards, NSW.

- Hinkson, M. 2001, Aboriginal Sydney: a guide to important places of the past and present, Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra.

- Hinkson, M. 2002, Exploring 'Aboriginal' sites in Sydney: a shifting politics of place, in Aboriginal History, Vol.26, p.63-77.

- Horner, J. 1980, 'Aborigines and the sesquicentenary: the Day of Mourning', Australia 1938: A Bicentenary History Bulletin, No. 3, 44-51.

- Horton, D. (ed) 1994, Encylopedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History, Society and Culture, Aboriginal Studies Press, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies: Canberra.

- Foley, G. 2001, Black Power in Redfern 1968-1972, accessed at http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/essays/essay_1.html on 10 September 2007.

- Foley, G. 2005, Day of Mourning Protest (26 January 1938) accessed at http://www.reasoninrevolt.net.au/biogs/E000336b.htm) on 10 September 2007. .

- Foy, M. 1935, The Romance of the house of Foy: published in connection with the golden jubilee of Mark Foy's Ltd, Sydney 1885-1935, Harbour Newspaper and Publishing: Sydney.

- Joint Committee on Native Title and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Fund 1999, Review of the Indigenous Land Corporation Annual Report 1997-98, Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra.

- Jumbunna Centre for Australian, Indigenous Studies, Education and Research (JCAISER) 1994, Site report: building at 150-152 Elizabeth St, Sydney, venue of the 'Day of Mourning' Aboriginal conference January 26, 1938. Unpublished Report to Australian Heritage Commission: Canberra.

- Langton, ML. 1987, The Day of Mourning. In Spearitt P, B Gammage (eds.) Australians, 1938. Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates: Broadway.

- Martin, C. 1996 Aboriginal history 'didn't end in 1788' accessed at http://www.greenleft.org.au/1996/232/14345 on 10 September 2007.

- Mesnage, G. 1998, Contested Spaces Contested Times, accessed at http://www.teachingheritage.nsw.edu.au/c_building/wc2_ahevent.html. on 10 September 2007.

- Muir, K. (Marnta Media Pty Ltd) 2003 Scoping an approach to identifying national heritage significance for sites associated with recognizing Indigenous rights, Report to the Australian Heritage Commission.

- National Capital Authority (nd) Reconciliation place: a lasting symbol of our shared journey, accessed at http://www.nationalcapital.gov.au/downloads/enhancing_and_maintaining/Reconciliation%20Place_A_lasting_symbol_of_our_shared_journey.pdf on 10 September 2007.

- Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination, 2004, New arrangements in Indigenous affairs. Dept. of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination: Canberra.

- Parbury, N. 1986, Survival: A history of Aboriginal life in New South Wales, Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs New South Wales: Sydney.

- Patten, J. T. 1938, The Australian Abo call : the voice of the Aborigines, April 1938, John Thomas Patten: Sydney.

- Patten J. T. & Ferguson W. 1938, Aborigines Claim Citizens Rights!: a statement of the case for the Aborigines Progressive Association, The Publicist: Sydney.

- Pearson, N. 1997, Seminar Session 3: A national document of reconciliation. Paper presented to Australian Reconciliation Convention 1997: Melbourne

- Pearson, N. 2007, Over 200 years without a place. Weekend Australian 25 August.

- NSW Heritage Office, 2000, Heritage Information Series: Assessing Historical Associations, NSW Heritage Office: Parramatta.

- NSW Heritage Register SHR Number 00773 1999, Cyprus-Hellene Club NSW Heritage Register: Sydney.

- O'Brien, G. 1997, Where Aborigines took a stand, another one looms. The Sydney Morning Herald 26 April 1997 page 9.

- Ramsey, A. 2004, 'Whatever you do, Mark, don't talk of unions', Sydney Morning Herald, 31 January 2004.

- Reason in Revolt Project, 2007, Salt Pan Creek Camp, accessed at http://www.reasoninrevolt.net.au/biogs/E000283b.htm on 10 September 2007.

- Register of the National Estate (RNE) Place Id. 19576. 1996. Cyprus Hellene Club & Australia Hall. Australian Heritage Commission (AHC): Canberra.

- Sutherland, T. 1998, City birthplace of black civil rights saved from developers. The Australian, 13 February 1998 page 6.

Attribution

![]()

External links

![]()