Curdlan

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| ChemSpider |

|

| E number | E424 (thickeners, ...) |

| Properties | |

| (C6H10O5)n | |

| Appearance | odourless white powder |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

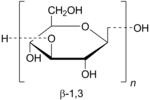

Curdlan is a water-insoluble linear beta-1,3-glucan, a high-molecular-weight polymer of glucose. Curdlan consists of β-(1,3)-linked glucose residues and forms elastic gels upon heating in aqueous suspension. Its was reported to be produced by Alcaligenes faecalis var. myxogenes in 1966 by Harada et al. [1]. Subsequently, the taxonomy of this non-pathogenic curdlan-producing bacterium has been reclassified as Agrobacterium species.[2]

Extracellular and capsular polysaccharides are produced by a variety of pathogenic and soil-dwelling bacteria. Curdlan is a neutral β-(1,3)-glucan, perhaps with a few intra- or interchain 1,6-linkages, produced as an exopolysaccharide by soil bacteria of the family Rhizobiaceae.[3] Four genes required for curdlan production have been identified in Agrobacterium sp. ATCC31749, which produces curdlan in extraordinary amounts, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens.[4] A putative operon contains crdS, encoding β-(1,3)-glucan synthase catalytic subunit,[5] flanked by two additional genes. A separate locus contains a putative regulatory gene, crdR. A membrane-bound phosphatidylserine synthase, encoded by pssAG, is also necessary for maximal production of curdlan of high molecular mass. Nitrogen starvation upregulates the curdlan operon and increases the rate of curdlan synthesis.[6]

Curdlan has numerous applications as a gelling agent in the food, construction, and pharmaceutical industries and has been approved as a food additive by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration.[7]

Recently, curdlan and its derivatives have been found to play a role in both innate and adaptive immunity leading to many new potential curdlan applications in biomedicine.[2]

See also

- Callose

- Gellan Gum

References

- ↑ Harada T., Fujimori K., Hirose S., Masada M. (1966). "Growth and Glucan (10C3K) Production by a Mutant of Alcaligenes faecalis var myxogenes in Defined Medium". Agric Biol Chem. 30: 764–769.

- 1 2 Xiao-Bei Zhan, Chi-Chung Lin, Hong-Tao Zhang (2012). "Recent advances in curdlan biosynthesis, biotechnological production, and applications". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 93: 525–531.

- ↑ McIntosh M, Stone BA, Stanisich VA (2005). "Curdlan and other bacterial (1-->3)-beta-D-glucans". Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 68 (2): 163–73. doi:10.1007/s00253-005-1959-5. PMID 15818477.

- ↑ Karnezis T, Epa VC, Stone BA, Stanisich VA (2003). "Topological characterization of an inner membrane (1-->3)-beta-D-glucan (curdlan) synthase from Agrobacterium sp. strain ATCC31749". Glycobiology. 13 (10): 693–706. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwg093. PMID 12851288.

- ↑ "Beta 1,3 glucan synthase catalytic subunit, UniProtKB/TrEMBL Q7D3X8 (Q7D3X8_AGRT5)".

- ↑ Ruffing AM, Chen RR (February 2012). "Transcriptome profiling of a curdlan-producing Agrobacterium reveals conserved regulatory mechanisms of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis". Microb Cell Fact. 11: 17. doi:10.1186/1475-2859-11-17. PMC 3293034. PMID 22305302.

- ↑ "Compendium of Food Additive Specifications (Addendum 7) Joint FAO/WHO Expert. Curdlan: New specification prepared at the 53rd JECFA (1999) and published in FNP 52 Add 7 (1999)".