Cultural impact of the Beatles

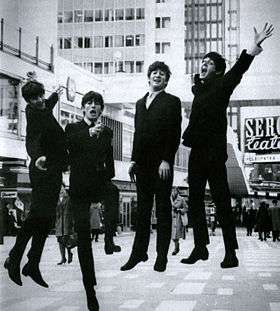

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960. With members John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, they became widely regarded as the foremost and most influential act of the rock era.[1] In the early 1960s, their enormous popularity first emerged as "Beatlemania", but as the group's music grew in sophistication, led by primary songwriters Lennon and McCartney, the band were integral to pop music's evolution into an art form and to the development of the counterculture of the 1960s.[2]

Their continued commercial and critical success assisted many cultural movements—including a shift from American artists' global dominance of rock and roll to British acts (British Invasion), the proliferation of young musicians in the 1960s who formed new bands, the album as the dominant form of record consumption over singles, the term "Beatlesque" used to describe similar-sounding artists, and several fashion trends. At the height of their popularity, Lennon controversially remarked that the group had become "more popular than Jesus". The Beatles were still challenged for record sales and artistic prestige, mainly by the Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, and the Rolling Stones. Many of the Beatles' music experiments were also not without precedent. However, no other acts provoked as many changes in the pop mainstream than the Beatles or Dylan, having opened new spaces for creative advancement and exploiting them to an exceeding degree. The Beatles' innovations notably contributed to the new psychedelic and progressive music, and some of the band's unusual production techniques later became part of normal recording practice.

As of 2009, the Beatles are the best-selling band in history, with estimated claimed sales of over 600 million records worldwide.[3][4] They have had more number-one albums on the British charts, fifteen,[5] and sold more singles in the UK, 21.9 million, than any other act.[6] They ranked number one on Billboard magazine's list of the all-time most successful Hot 100 artists, released in 2008 to celebrate the US singles chart's 50th anniversary.[7] As of 2016, they hold the record for most number-one hits on the Billboard Hot 100, with twenty.[8] They've also had myriad cover versions from a variety of artists, while "Yesterday" is one of the most covered songs in the history of recorded music.[9] In 1999, the Beatles were collectively included in Time magazine's compilation of the twentieth century's 100 most influential people.[10] In 2017, a study of AllMusic's catalog indicated the Beatles as the most frequently cited artist influence in its database.[11]

Emergence

Beatlemania

Regarding the ever-changing landscapes of popular music, musicologist Allan Moore notes; "Sometimes, audiences gravitate towards a centre. The most prominent period when this happened was in the early to mid 1960s when it seems that almost everyone, irrespective of age, class or cultural background, listened to the Beatles."[12][nb 1] On 9 February 1964, the Beatles gave their first live US television performance on The Ed Sullivan Show, watched by approximately 73 million viewers in over 23 million households,[13] or 34 per cent of the American population. Biographer Jonathan Gould writes that, according to the Nielsen rating service, it was "the largest audience that had ever been recorded for an American television program".[14]

The Beatles subsequently sparked the British Invasion of the US[15] and became a globally influential phenomenon.[16] During the previous four decades, the United States had dominated popular entertainment culture throughout much of the world, via Hollywood movies, jazz, the music of Broadway and Tin Pan Alley and, later, the rock and roll that first emerged in Memphis, Tennessee.[17] On 4 April 1964, the Beatles occupied the top five US chart positions, as well as 11 other positions in the Top 100.[18] As of 2013, they remain the only act to have done so, having also broken 11 other chart records in the Billboard Top 100 and Billboard 200.[19] Author Luis Sanchez wrote: "to grasp the mania that persists in our collective imagination is to follow the proselytizing drift of a question like 'Who is your favorite Beatle?'"[20] By August 1965, they "had transformed into an abstraction of their own success, a phenomenon to be devoured rather than heard. The pressure of that phenomenon led to one of the most mythologized of pop career reversals. ... quietly resigning from the drudge of touring to get serious about their art."[20]

Contemporary rivals

—Nicholas Cooke and Anthony Pople, The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Music[21]

The Beatles maintained their most significant competition with Bob Dylan,[22] the Rolling Stones[23] and the Beach Boys.[24][nb 2] Dylan and the Stones were symbolic of the nascent youth revolt against institutional authority, something that was not immediately recognisable within the Beatles until after 1966.[27] The Beatles' initial clean-cut personas contrasted with the Rolling Stones' "bad boy" image, and so the music press forged a rivalry between the two,[28] but as author Barry Miles says, "[it was] to give themselves something to write about, [and] there was actually no contest between the two groups in anything other than chart positions."[29][nb 3] The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame states that, with regard to 1960s rock bands, the Beach Boys "place second only to the Beatles in terms of their overall impact on the [US] top 40" and were the Beatles' "most serious competitors on a creative level, too".[31] Following the widespread changes brought about by the Beatles' arrival in the United States, author Mitchell K. Hall writes, "for a time the Beach Boys provided the Beatles with their most consistent American artistic and commercial competition."[32] Another group, the Byrds, were widely celebrated as the American answer to the Beatles, and while their long-term influence has proven to be comparable to the Beatles and the Beach Boys, the Byrds' record sales failed to match those groups.[33]

Dylan is described by Ian MacDonald as "the only figure to have matched The Beatles' influence on popular culture since 1945"[34] and by Charles Kaiser as "their most important rival. ... For the next six years [after 1964], the contest between Dylan and the Beatles would be one of the most productive of all modern musical rivalries. The Beatles made it clear that they regarded Bob Dylan as the musical force to be reckoned with, and Dylan reciprocated these feelings."[35] In August 1964, the Beatles met Dylan in person,[36] and he proceeded to introduce them to cannabis.[37] Gould points out the musical and cultural significance of this meeting, before which the musicians' respective fanbases were "perceived as inhabiting two separate subcultural worlds": Dylan's audience of "college kids with artistic or intellectual leanings, a dawning political and social idealism, and a mildly bohemian style" contrasted with their fans, "veritable 'teenyboppers' – kids in high school or grade school whose lives were totally wrapped up in the commercialised popular culture of television, radio, pop records, fan magazines, and teen fashion. They were seen as idolaters, not idealists."[38] Within a year, "the distinctions between the folk and rock audiences would have nearly evaporated [and the group's] audience ... [was] showing signs of growing up."[38] In this period, no other acts provoked as many changes in the pop mainstream than the Beatles or Dylan, having opened new spaces for creative advancement and exploiting them to an exceeding degree.[39][nb 4]

According to Simon Philo, the Dylan–Beatles rivalry was "put on hold" after Dylan was left to convalesce from his July 1966 motorcycle accident. Consequently, the Beatles "publicly anointed a new favorite and rival in chief, the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson".[41] Previously in July 1964, the Beach Boys had achieved their first number one single with "I Get Around", which represented the start of an unofficial rivalry between the Beatles and Wilson, principally for McCartney.[31][nb 5] The Beatles and the Beach Boys inspired each other with their artistry and recording techniques, pushing them further out in the studio.[21][29] According to Sanchez, in 1965, "Dylan was rewriting the rules for pop success" with his music and image, and it was at this juncture that Wilson "led The Beach Boys into a transitional phase in an effort to win the pop terrain that had been thrown up for grabs."[45] Wilson then produced the 1966 works Pet Sounds and "Good Vibrations". For the annual best-band poll conducted by NME between 1963 and 1969, 1966 was the only year that the Beatles did not win, losing to the Beach Boys.[46] According to author Carys Wyn Jones, the interplay between these two groups during the Pet Sounds era remains one of the most noteworthy episodes in rock history.[47] In 2003, when Rolling Stone magazine created its list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time", the publication placed Pet Sounds second to honour its influence on the highest ranked album, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967).[48]

Influence on music

Songcraft, production, and popular discourse

.jpg)

Writing for AllMusic, music critic Richie Unterberger recognises the Beatles as both "the greatest and most influential act of the rock era" and a group that "introduced more innovations into popular music than any other rock band of the 20th century".[49] In Rolling Stone magazine's Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (2001), the editors define the band's influence as follows:

The impact of the Beatles – not only on rock & roll but on all of Western culture – is simply incalculable … [A]s personalities, they defined and incarnated '60s style: smart, idealistic, playful, irreverent, eclectic. Although many of their sales and attendance records have since been surpassed, no group has so radically transformed the sound and significance of rock & roll. ... [they] proved that rock & roll could embrace a limitless variety of harmonies, structures, and sounds; virtually every rock experiment has some precedent on Beatles record.[50]

The Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership, along with the partnership between Rolling Stones' Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, as well as other British Invasion songwriters, inspired changes to the music industry because they were bands that wrote and performed their own music. This trend threatened the professional songwriters that dominated the American music industry. Ellie Greenwich, a Brill Building songwriter, said, “When the Beatles and the entire British Invasion came in, we were all ready to say, ‘Look, it’s been nice, there’s no more room for us… It’s now the self-contained group- males, certain type of material. What do we do?"[51] Rolling Stone editors elaborated: "One of the first rock groups to write most of its own material, they inaugurated the era of self-contained bands and forever centralized pop ... Their music, from the not-so-simple love songs they started with to their later perfectionist studio extravaganzas, set new standards for both commercial and artistic success in pop."[50]

In response to the Beatles' 1964 breakthrough, music writers started including pop and rock music in serious discussion.[52][nb 6] The dominance of the single as the primary medium of music sales changed with the release of several iconic concept albums in the 1960s, such as Sgt. Pepper's, Pet Sounds, A Christmas Gift for You from Phil Spector (1963), and the Mothers of Invention's Freak Out! (1966).[54] In January 1966, Billboard magazine cited the initial US sales of the Beatles' 1965 album Rubber Soul (1.2 million copies over nine days) as evidence of teenage record-buyers increasingly moving towards the LP format.[55] According to author David N. Howard, the standard of the all-original compositions on Rubber Soul was also responsible for a shift in focus from singles to creating albums without the usual filler tracks.[56] Rolling Stone's Andy Greene credits Sgt. Pepper's with marking the beginning of the Album era.[57] The musicologist Oliver Julien credits Sgt. Pepper with contributing towards the evolution of long-playing albums from a "distribution format" to a "creation format".[58] In musicologist Allen Moore's view, the album assisted "the cultural legitimization of popular music" while providing an important musical representation of its generation.[59] It is regarded by journalists as having influenced the development of the counterculture of the 1960s.[60]

The Beatles reinvented and expanded the terms of commercial and artistic achievement, treading new ground for their willingness to experiment and take risks.[20] One criticism of the group's work is that none of it was truly unprecedented. Author Bill Martin objects to this notion: "There has always been experimentation in rock music ... Rock music is synthesis and transmutation ... [but] what was original about the Beatles is that they synthesized and transmuted more or less everything, they did this in a way that reflected their time, they reflected their time in a way that spoke to a great part of humanity, and they did all of this really, really well."[61] Unterberger adds: "they were among the few artists of any discipline that were simultaneously the best at what they did and the most popular at what they did. Relentlessly imaginative and experimental, the Beatles grabbed hold of the international mass consciousness in 1964 and never let go for the next six years, always staying ahead of the pack in terms of creativity but never losing their ability to communicate their increasingly sophisticated ideas to a mass audience. Their supremacy as rock icons remains unchallenged to this day, decades after their breakup in 1970."[49]

Genres and stylistic trends

Growth of rock bands

The Beatles' impact on the US was particularly strong, where a garage rock phenomenon had already begun, with hits such as "Louie Louie" by the Kingsmen. The movement received a major lift following the group's historic appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show watched by a record-breaking viewing audience of a nation mourning the recent death of President John F. Kennedy.[62][63][64] Bill Dean writes: "It's impossible to say just how many of America's young people began playing guitars and forming bands in the wake of The Beatles' appearance on the Sullivan show. But the anecdotal evidence suggests thousands – if not hundreds of thousands or even more – young musicians across the country formed bands and proceeded to play."[65]

Tom Petty, who played in two garage bands in Gainesville, Florida during the 1960s, is quoted mentioning the Beatles' appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show and how it influenced him to be in a band. According to him: "Within weeks of that, you could drive through literally any neighborhood in Gainesville and you would hear the strains of garage bands playing ... I mean everywhere. And I'd say by a year from that time, Gainesville probably had 50 bands."[65] For many, particularly young baby boomers, the Beatles' visit reignited the sense of excitement and possibility that had been momentarily taken by Kennedy's assassination.[62][65][66][67] Much of this new excitement would be expressed in music, sometimes much to the chagrin of parents and elders, as kids raced to start bands by thousands, and this proliferation of new groups was not limited to the United States.[62][65][66][68]

While the Beatles are often credited for sparking a musical revolution, research conducted by the Queen Mary University of London and Imperial College London suggests that the changes sparked by the band were already developing long before they entered the US. The study, which looks at shifts in chord progressions, beats, lyrics and vocals, shows that American music in the beginning of the 1960s was already moving away from mellow sounds like doo-wop and into more energetic rock styles. Professor Armand Lero argues that the Beatles' innovations have been overstated by music historians: "They didn’t make a revolution or spark a revolution, they joined one. The trend is already emerging and they rode that wave, which accounts for their incredible success."[69][nb 7] Beatles biographer Mark Lewisohn disagreed with the research by Queen Mary University, saying it "[doesn't] stack up ... Speak to anyone who was a young person in the US when The Beatles arrived and they will tell you how much of a revolution it was. They were there and they will tell you that the Beatles revolutionised everything."[69]

Jangle pop and folk rock

George Harrison was one of the first people to own a Rickenbacker 360/12, a guitar with twelve strings, the low eight of which are tuned in pairs, one octave apart; the higher four are pairs tuned in unison. The Rickenbacker is unique among twelve-string guitars in having the lower octave string of each of the first four pairs placed above the higher tuned string. This, and the naturally rich harmonics produced by a twelve-string guitar provided the distinctive overtones found on many of the Beatles' recordings.[70]

His use of this guitar during the recording of A Hard Day's Night (1964) helped to popularise the model, and the jangly sound became so prominent that Melody Maker termed it the Beatles' "secret weapon".[71] Roger McGuinn liked the effect so much that it became his signature guitar sound with the Byrds.[72] While the Everly Brothers and the Searchers laid the foundations for jangle pop in the late 1950s to mid 1960s, the Beatles and the Byrds are commonly credited with launching the popularity of the "jangly" sound that defined the genre.[73] In addition to the Byrds and Dylan, the Beatles were a huge influence on the folk rock explosion that would follow in the next year.[49]

British pop and power pop

With the rise of the Beatles in 1963, the terms Mersey sound and Merseybeat were applied to bands and singers from Liverpool, and this was the first time in British pop music that a sound and a location were linked together.[74] The origins of power pop date back to the early to mid 1960s with what AllMusic calls: "a cross between the crunching hard rock of the Who and the sweet melodicism of the Beatles and the Beach Boys, with the ringing guitars of the Byrds thrown in for good measure".[75]

Psychedelia and progressiveness

Progressive rock (or art rock) grew out of the classically-minded strains of British psychedelia.[76] In 1966, the level of social and artistic correspondence among British and American rock musicians dramatically accelerated for bands like the Beatles, the Beach Boys and the Byrds who fused elements of cultivated music with the vernacular traditions of rock.[77] According to Everett, the Beatles' "experimental timbres, rhythms, tonal structures, and poetic texts" on their albums Rubber Soul and Revolver "encouraged a legion of young bands that were to create progressive rock in the early 1970s".[78] Academics Paul Hegarty and Martin Halliwell identify the Beatles "not merely as precursors of prog but as essential developments of progressiveness in its early days".[79][nb 8] After the release of Rubber Soul, many "baroque-rock" works would soon appear, particularly due to its track "In My Life".[80][nb 9]

Citing a quantitative study of tempos in music from the era, musicologist Walter Everett identifies Rubber Soul as a work that was "made more to be thought about than danced to", and an album that "began a far-reaching trend" in its slowing-down of the tempos typically used in pop and rock music.[83] Although the Kinks, the Yardbirds and the Beatles themselves (with "Ticket To Ride") had incorporated droning guitars to mimic the qualities of the sitar, Rubber Soul's "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" is generally credited as sparking a musical craze for the sound of the instrument in the mid-1960s — a trend which would later be associated with the growth of raga rock, Indian rock, and the essence of psychedelic rock.[84][85] In terms of bridging the relationship between music and hallucinogens, the Beatles and the Beach Boys were the most pivotal.[86] Revolver ensured that psychedelic pop emerged from its underground roots and into the mainstream.[87]

Author Carys Wyn Jones locates Sgt. Pepper's, along with Pet Sounds, to the beginning of art rock.[88] Both albums are largely viewed as beginnings in the progressive rock genre due to their lyrical unity, extended structure, complexity, eclecticism, experimentalism and influences derived from classical music forms.[89] For several years following Sgt. Pepper's release, straightforward rock and roll was supplanted by a growing interest in extended form.[90] Several of the English psychedelic bands who followed in the wake of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's developed characteristics of the Beatles' music (specifically their classical influence) further than either the Beatles or contemporaneous West Coast psychedelic bands.[91] AllMusic states that the first wave of art rock musicians were inspired by Sgt. Pepper's and believed that for rock music to grow artistically, they should incorporate elements of European and classical music to the genre.[76]

Live concerts

The Beatles were the first entertainment act to stage a large stadium concert. At Shea Stadium in New York City on Sunday, 15 August 1965, the group opened their 1965 North American tour to a record audience of 55,600. The event sold out in 17 minutes.[92] It was the first concert to be held at a major outdoor stadium and set records for attendance and revenue generation, demonstrating that outdoor concerts on a large scale could be successful and profitable. The Beatles returned to Shea for a highly successful encore in August 1966.

Influence on fashions

Haircut

The Beatle haircut, also known as the "mop-top" (or moptop), because of its resemblance to a mop, or "Arthur" among fans,[nb 10] is a mid-length hairstyle named after and popularised by the Beatles, and widely mocked by many adults.[93] It is a straight cut – collar-length at the back and over the ears at the sides, with a straight fringe (bangs).[nb 11] Because of the immense popularity of the Beatles, the haircut was widely imitated worldwide between 1964 and 1966. Their hair-style led toy manufacturers to begin producing real-hair and plastic "Beatle Wigs". Lowell Toy Manufacturing Corp. of New York was licensed to make "the only AUTHENTIC Beatle Wig". There have been many attempts at counterfeiting, but in its original packaging this wig has become highly collectible.

Mikhail Safonov wrote in 2003 that in the Brezhnev-dominated Soviet Union, mimicking the Beatles' hairstyle was seen as highly rebellious. Young people were called "hairies" by their elders, and were arrested and forced to have their hair cut in police stations.[94]

Beatle boots

Beatle boots are tight-fitting, Cuban-heeled, ankle-length boots with a pointed toe. They originated in 1963 when Brian Epstein discovered Chelsea boots while browsing in the London footwear company Anello & Davide. He consequently commissioned four pairs (with the addition of Cuban heels) for the Beatles to complement their new suit image upon their return from Hamburg, who wore them under drainpipe trousers.[95]

In popular culture

Cover versions

In May 1966, John Lennon said of people covering their songs, "Lack of feeling in an emotional sense is responsible for the way some singers do our songs. They don't understand and are too old to grasp the feeling. Beatles are really the only people who can play Beatle music."[96]

Awards and accolades

Notes

- ↑ However, as he continues, "by 1970 this monolothic position had again broken down. Both the Edgar Broughton Band's 'Apache dropout' and Edison Lighthouse's 'Love grows' were released in 1970 with strong Midlands/London connections, and both were audible on the same radio stations, but were operating according to very different aesthetics."[12]

- ↑ The Beatles kept abreast of their sales rankings in comparison to other groups like the Beach Boys,[25] and often found new musical and lyrical avenues by listening to their contemporaries.[26]

- ↑ In 1971, Lennon responded to disparaging comments the Stones were making of the Beatles: "I resent the implication that the Rolling Stones are like revolutionaries and that the Beatles weren't. The Stones are not in the same class, music-wise or power-wise, never were."[30]

- ↑ Sanchez notes that during the second half of 1965, the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and Dylan all faced the option of "gambling with the audience who granted their music whatever life it had; or they could stay comfortable inside the success they’d already won".[40] After Dylan met the Beatles, he went "electric" in a move that subverted notions of folk authenticity.[38]

- ↑ By the time the Beatles arrived in the US, the Beach Boys (along with the Four Seasons) had already established themselves as major chart successes.[42] The Beach Boys and the Four Seasons were also the only two American groups to enjoy major chart success before, during, and after the British Invasion.[43] For Wilson, the Beatles ultimately "eclipsed a lot [of what] we’d worked for ... [they] eclipsed the whole music world."[44]

- ↑ During the mid 1960s, pop music made repeated forays into new sounds, styles, and techniques that inspired public discourse among its listeners. The word "progressive" was frequently used, and it was thought that every song and single was to be a "progression" from the last.[53]

- ↑ Before the Beatles reached America, bands like the Beach Boys and the Top Notes were already in record charts with "Surfin' U.S.A." (1963) and "Twist and Shout" (1961), respectively. McCartney is quoted before the Beatles left for the United States in 1964: "They've got their own groups. What are we going to give them that they don't already have?"[69]

- ↑ This is in addition to the Beach Boys, the Doors, the Pretty Things, the Zombies, the Byrds, the Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd.[79]

- ↑ Slate's Forrest Wickman credits Brian Wilson and the Beatles' producer, George Martin, as some of the men "most responsible" for the move into baroque pop.[81] The Beatles benefited from the classical music skills of Martin, who played a baroque harpsichord solo on "In My Life".[80] However, the instrument used was actually a piano recorded on tape at half speed.[82]

- ↑ At a press conference at the Plaza Hotel in New York, shortly after the Beatles' arrival in the United States, Harrison was asked by a reporter, "What do you call your hairstyle?" He replied "Arthur". The scene was recreated in the movie A Hard Day's Night with the reporter asking George Harrison, "What would you call that, uh, hairstyle you're wearing?"

- ↑ As a schoolboy in the mid 1950s, Jürgen Vollmer had left his hair hanging down over his forehead one day after he had gone swimming, not bothering to style it. John Lennon is quoted in The Beatles Anthology as follows: "Jürgen had a flattened-down hairstyle with a fringe in the back, which we rather took to." In late 1961, Vollmer moved to Paris. McCartney said in a 1979 radio interview: "We saw a guy in Hamburg whose hair we liked. John and I were hitchhiking to Paris. We asked him to cut our hair like he cut his." McCartney also wrote in a letter to Vollmer in 1989: "George explained in a 60s interview that it was John and I having our hair cut in Paris which prompted him to do the same. ... We were the first to take the plunge."

References

- ↑ Unterberger, Richie. Cultural impact of the Beatles at AllMusic. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ Frontani 2007, p. 125.

- ↑ "Beatles' remastered box set, video game out". CNNMoney.com. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Hotten, Russell (4 October 2012). "The Beatles at 50: From Fab Four to fabulously wealthy". BBC News. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Glennie 2012.

- ↑ Official Chart Company 2012.

- ↑ Billboard 2008a.

- ↑ Trust, Gary (21 March 2016). "Rihanna Rules Hot 100 for Fifth Week, Ariana Grande Debuts at No. 10". Billboard. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Most Recorded Song". Guinness World Records. 2009. Archived from the original on 10 September 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ↑ Loder 1998.

- ↑ Kopf, Dan; Wong, Amy X. (October 7, 2017). "A definitive list of the musicians who influenced our lives most". Quartz.

- 1 2 Moore 2016, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Lewisohn 1992, p. 137.

- ↑ Gould 2007, p. 3.

- ↑ Everett 1999, p. 277.

- ↑ Gould 2007, p. 8.

- ↑ Gould 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ MacDonald 2007, p. 417.

- ↑ Caulfield, Keith; Trust, Gary; Letkemann, Jessica (7 February 2014). "The Beatles' American Chart Invasion: 12 Record-Breaking Hot 100 & Billboard 200 Feats". Billboard.

- 1 2 3 Sanchez 2014, p. 73.

- 1 2 Cook & Pople 2004, p. 441.

- ↑ Kaiser 1988, p. 199: "their most important rival" Robins 2016, p. 103: "the Beatles' main rival."

- ↑ Schinder & Schwartz 2008, p. 211: "the Beatles' only serious competitor, in terms of popularity, prestige, and musical influence"

- ↑ Schinder & Schwartz 2008, p. 102: "When the British Invasion took hold of the American teen consciousness in 1964, [the Beach Boys] posed the only serious threat to the Fab Four's chart supremacy" Hall 2014, p. 62: "for a time … their most consistent American artistic and commercial competition"

- ↑ Runco 2014, p. 154.

- ↑ Harry 2000, pp. 99, 217, 357, 1195.

- ↑ MacDonald 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ Fried, Titone & Weiner 1980, p. 185.

- 1 2 Miles 1998, p. 280.

- ↑ Lange 2008, p. 91.

- 1 2 Moskowitz 2015, pp. 42, 47.

- ↑ Hall 2014, p. 62.

- ↑ Schinder & Schwartz 2008, pp. 257–258.

- ↑ MacDonald 2007, p. 124.

- ↑ Kaiser 1988, p. 199.

- ↑ Gould 2007, p. 252.

- ↑ Miles 1998, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 Gould 2007, pp. 252–253.

- ↑ Sanchez 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ Sanchez 2014, p. 69.

- ↑ Philo 2014, p. 105.

- ↑ Davis 1981, p. 75.

- ↑ Tuyl 2004, p. 163.

- ↑ Sanchez 2014, pp. 70.

- ↑ Sanchez 2014, p. 76.

- ↑ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 184–185, 1966 NME polls; Sanchez 2014, p. 4, "On the heels of Pet Sounds and 'Good Vibrations,' talk of the next big pop acquisition became like open secret. For a moment in the mid-60s, it seemed Brian would take his place next to the Beatles and Bob Dylan on the board of pop music luminaries."

- ↑ Jones 2008, p. 56.

- ↑ Jones 2008, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- 1 2 George-Warren 2001, p. 56.

- ↑ Inglis, Ian (2000). The Beatles, Popular Music and Society. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-312-22236-X.

- ↑ Jones 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ Hewitt & Hellier 2015, p. 162.

- ↑ Julien 2013, pp. 30, 160.

- ↑ Staff writer (15 January 1966). "Teen Market Is Album Market". Billboard. p. 36. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ Howard 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Kokenes, Chris (30 April 2010). "'A Day in the Life' lyrics to be auctioned". CNN. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Julien 2013, p. 159.

- ↑ Moore 1997, p. 62: "the cultural legitimization of popular music"; Moore 1997, pp. 68–69: a musical representation of its generation.

- ↑ "Sgt. Pepper at 40: The Beatles' masterpiece changed popular music". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 1 June 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ↑ Martin 2015, pp. 3, 13–14.

- 1 2 3 Lemlich 1992, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Kauppila, Paul (October 2006). "The Sound of the Suburbs: A Case Study of Three Garage Bands in San Jose, California during the 1960s". San Jose State University SJSU Scholar Works. San Jose, California: San Jose State University Faculty Publications: 7–8, 10–11.

- ↑ Spitz 2013, pp. 5, 39, 42–49.

- 1 2 3 4 Dean, Bill (9 February 2014). "50 Years Ago Today, The Beatles Taught a Young America to Play". Scene. Gainesville.com. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- 1 2 Gilmore, Mikal (23 August 1990). Wenner, Jann, ed. "Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and the Rock of the Sixties". Rolling Stone. No. 585. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Spitz 2013, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Spitz 2013, pp. 55–59.

- 1 2 3 Knapton, Sarah (5 May 2015). "The Beatles 'did not spark a musical revolution in America'". The Telegraph.

- ↑ Everett 2001, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Babiuk 2002, p. 120: "secret weapon"; Leng 2006, p. 14: Harrison helped to popularize the model.

- ↑ Doggett & Hodgson 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ LaBate, Steve (December 18, 2009). "Jangle Bell Rock: A Chronological (Non-Holiday) Anthology… from The Beatles and Byrds to R.E.M. and Beyond". Paste. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Inglis 2010, p. 11.

- ↑ "Power Pop". AllMusic. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Prog-Rock". AllMusic.

- ↑ Holm-Hudson 2013, p. 85.

- ↑ Everett 1999, p. 95.

- 1 2 Hegarty & Halliwell 2011, p. 11.

- 1 2 Harrington 2002, p. 191.

- ↑ Wickman, Forrest (March 9, 2016). "George Martin, the Beatles Producer and "Fifth Beatle," Is Dead at 90". Slate.

- ↑ Myers, Marc (October 30, 2013). "Bach & Roll: How the Unsexy Harpsichord Got Hip". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Everett 2001, pp. 311–12.

- ↑ Bellman 1998, p. 292.

- ↑ Howlett, Kevin (2009). Rubber Soul (CD booklet). The Beatles. Parlophone Records.

- ↑ Longman, Molly (May 20, 2016). "Had LSD Never Been Discovered Over 75 Years Ago, Music History Would Be Entirely Different". Music.mic.

- ↑ Anon. "Psychedelic Pop". AllMusic.

- ↑ Jones 2008, p. 49.

- ↑ Macan 1997, p. 15,20.

- ↑ Moore 1997, p. 72.

- ↑ Macan 1997, p. 21.

- ↑ The Beatles Off The Record. London:Omnibus Press p193. ISBN 0-7119-7985-5

- ↑ Gilliland 1969, show 27, track 4.

- ↑ The Guardian

- ↑ Sims, Josh (1999). Rock Fashions. Omnibus Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0-7119-7733-X.

- ↑ "Flip Magazine, May 1966". Archived from the original on 20 May 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

Bibliography

- Babiuk, Andy (2002). Bacon, Tony, ed. Beatles Gear: All the Fab Four's Instruments, from Stage to Studio (Revised ed.). Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-731-8.

- Bellman, Jonathan (1998). The Exotic in Western Music. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1-55553-319-1.

- Cook, Nicholas; Pople, Anthony (2004). The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66256-7.

- Davis, Allen Freeman, ed. (1981). For Better or Worse: the American Influence in the World. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-22342-6.

- Doggett, Peter; Hodgson, Sarah (2004). Christie's Rock and Pop Memorabilia. Pavilion. ISBN 978-0-8230-0649-6.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Everett, Walter (2001). The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men Through Rubber Soul. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514105-4.

- Fried, Goldie; Titone, Robin; Weiner, Sue (1980). The Beatles A-Z. Methuen. ISBN 978-0-416-00781-7.

- Frontani, Michael R. (2007). The Beatles: Image and the Media. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-965-1. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- George-Warren, Holly (ed.) (2001). The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll. New York, NY: Fireside/Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 0-7432-0120-5.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-35338-2.

- Hall, Mitchell K. (2014). The Emergence of Rock and Roll: Music and the Rise of American Youth Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-05357-4.

- Harry, Bill (2000). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Revised and Updated. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-0-7535-0481-9.

- Hegarty, Paul; Halliwell, Martin (2011). Beyond and Before: Progressive Rock Since the 1960s. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-2332-0.

- Hewitt, Paolo; Hellier, John (2015). Steve Marriott: All Too Beautiful. Dean Street Press. ISBN 978-1-910570-69-2.

- Holm-Hudson, Kevin, ed. (2013). Progressive Rock Reconsidered. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-71022-4.

- Howard, David N. (2004). Sonic Alchemy: Visionary Music Producers and Their Maverick Recordings. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-634-05560-7.

- Inglis, Ian (2010). "Historical approaches to Merseybeat". The Beat Goes on: Liverpool, Popular Music and the Changing City (editors Marion Leonard, Robert Strachan). Liverpool University Press. p. 11.

- Jones, Carys Wyn (2008). The Rock Canon. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6244-0.

- Jones, Steve, ed. (2002). Pop Music and the Press. Temple University Press. ASIN B00EKYXY0K. ISBN 9781566399661.

- Julien, Oliver (2013). Sgt. Pepper and the Beatles: It Was Forty Years Ago Today. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013. ISBN 9781409493822.

- Kaiser, Charles (1988). 1968 in America: Music, Politics, Chaos, Counterculture, and the Shaping of a Generation. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3530-8.

- Lemlich, Jeffrey M. (1992). Savage Lost: Florida Garage Bands of the '60s and Beyond (First ed.). Plantation, FL: Distinctive Publishing Corporation. ISBN 0-942963-12-1.

- Lange, Larry (2008). The Beatles Way: Fab Wisdom for Everyday Life. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-1681-4.

- Leng, Simon (2006) [2003]. While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison. SAF Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4234-0609-9.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1992). The Complete Beatles Chronicle:The Definitive Day-By-Day Guide To the Beatles' Entire Career (2010 ed.). Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-534-0.

- Loder, Kurt (8 June 1998). "The Time 100". Time. New York. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- Macan, Edward (1997). Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509887-7.

- MacDonald, Ian (2007). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3.

- Martin, Bill (2015). Avant Rock: Experimental Music from the Beatles to Bjork. Open Court Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8126-9939-5.

- Miles, Barry (1998). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-5249-7.

- Moore, Allan F. (1997). The Beatles: Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57484-6.

- Moore, Allan F. (2016). Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-05265-4.

- Moskowitz, David V. (2015). The 100 Greatest Bands of All Time: A Guide to the Legends Who Rocked the World [2 volumes]: A Guide to the Legends Who Rocked the World. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-0340-6.

- Philo, Simon (2014). British Invasion: The Crosscurrents of Musical Influence. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8108-8627-8.

- Robins, Wayne (2016). A Brief History of Rock, Off the Record. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-92345-7.

- Runco, Mark A. (2014). Creativity: Theories and Themes: Research, Development, and Practice. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-12-410522-5.

- Sanchez, Luis (2014). The Beach Boys' Smile. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62356-956-3.

- Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2008). Icons of Rock. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33846-5.

- Shephard, Tim; Leonard, Anne, eds. (2013). The Routledge Companion to Music and Visual Culture. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 9781135956462.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-80352-6.

- Spitz, Bob (2013). Koepp, Stephen, ed. The Beatles Invasion (TIME Magazine special issue). New York: TIME Books.

- Tuyl, Ian Van (2004). Popstrology: The Art and Science of Reading the Popstars. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-58234-422-5.

External links

- Gilliland, John (1969). "The British Are Coming! The British Are Coming!: The U.S.A. is invaded by a wave of long-haired English rockers" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Kot, Greg (21 October 2014). "Were The Rolling Stones Better Than The Beatles?". BBC.

- Lewisohn, Mark (20 September 2013). "The Beatles: the Sixties Start Here". The Telegraph.

- McMillian, John (4 February 2014). "Age-old debate: Beatles vs. Stones". CBS News.