Crimes and Misdemeanors

| Crimes and Misdemeanors | |

|---|---|

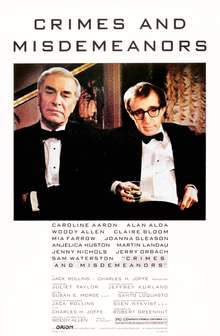

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Woody Allen |

| Produced by | Robert Greenhut |

| Written by | Woody Allen |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Franz Schubert |

| Cinematography | Sven Nykvist |

| Edited by | Susan E. Morse |

Production company |

Jack Rollins & Charles H. Joffe Productions |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $19 million |

| Box office | $18.3 million[2] |

Crimes and Misdemeanors is a 1989 American existential comedy-drama film written and directed by Woody Allen, who stars alongside Martin Landau, Mia Farrow, Anjelica Huston, Jerry Orbach, Alan Alda, Sam Waterston and Joanna Gleason.

The film was met with critical acclaim, and was nominated for three Academy Awards: Woody Allen, for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay, and Martin Landau, for Best Actor in a Supporting Role. In several publications, Crimes and Misdemeanors has been ranked as one of Allen's greatest films.

Plot

The story follows two main characters: Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), a successful ophthalmologist, and Clifford Stern (Woody Allen), a small-time documentary filmmaker.

Judah, a respectable family man, is having an affair with flight attendant Dolores Paley (Anjelica Huston). After it becomes clear to her that Judah will not end his marriage, Dolores threatens to disclose the affair to Judah's wife, Miriam (Claire Bloom). She is also aware of some questionable financial deals Judah has made, which adds to his stress. He confides in a patient, Ben (Sam Waterston), a rabbi who is rapidly losing his eyesight. Ben advises openness and honesty between Judah and his wife, but Judah does not wish to imperil his marriage. Desperate, Judah turns to his brother, Jack (Jerry Orbach), a gangster, who hires a hitman to kill Dolores. Before her corpse is discovered, Judah retrieves letters and other items from her apartment in order to cover his tracks. Stricken with guilt, Judah turns to the religious teachings he had rejected, believing for the first time that a just God is watching him and passing judgment.

Cliff, meanwhile, has been hired by his pompous brother-in-law, Lester (Alan Alda), a successful television producer, to make a documentary celebrating Lester's life and work. Cliff grows to despise him. While filming and mocking the subject, Cliff falls in love with Lester's associate producer, Halley Reed (Mia Farrow). Despondent over his failing marriage to Lester's sister Wendy (Joanna Gleason), he woos Halley, showing her footage from his ongoing documentary about Prof. Louis Levy (psychologist Martin S. Bergmann[3]), a renowned philosopher. He makes sure Halley is aware that he is shooting Lester's documentary merely for the money so he can finish his more meaningful project with Levy.

Cliff's dislike for Lester becomes evident during the first screening of the film. It juxtaposes footage of Lester with clownish poses of Benito Mussolini addressing a throng of supporters from a balcony. It also shows Lester yelling at his employees and clumsily making a pass at an attractive young actress. Lester fires him. Cliff learns that Professor Levy, whom he had been profiling on the strength of his celebration of life, has committed suicide, leaving a curt note, "I've gone out the window." When Halley visits to comfort him, he makes a pass at her, which she gently rebuffs, telling him she isn't ready for another romance.

Adding to Cliff's burdens, Halley leaves for London, where Lester is offering her a producing job; when she returns several months later, Cliff is astounded to discover that she and Lester are engaged. Hearing that Lester sent Halley white roses "round the clock, for days" while they were in London, Cliff is crestfallen as he realizes he is incapable of that kind of ostentatious display. His last romantic gesture to Halley had been a love letter which he had mostly plagiarized from James Joyce.

In the final scene, Judah and Cliff meet by happenstance at the wedding of the daughter of Rabbi Ben, who is Cliff's brother-in-law and Judah's patient. Judah has worked through his guilt and is enjoying life once more; the murder had been blamed on a drifter with a criminal record. He draws Cliff into a supposedly hypothetical discussion that draws upon his moral quandary. Judah says that with time, any crisis will pass; but Cliff morosely claims instead that one is forever fated to bear one's burdens for "crimes and misdemeanors". Judah cheerfully leaves the wedding party with his wife, and Cliff is left sitting alone, dejected. Ben the rabbi, who is now blind, shares a dance with his daughter while the voice of Prof. Levy is heard, saying that the universe is a dark and indifferent place which human beings fill with love, in the hope that it will give the void a meaning.

Cast

- Alan Alda as Lester

- Woody Allen as Cliff Stern

- Caroline Aaron as Barbara

- Claire Bloom as Miriam Rosenthal

- Mia Farrow as Halley Reed

- Joanna Gleason as Wendy Stern

- Anjelica Huston as Dolores Paley

- Martin Landau as Judah Rosenthal

- Jenny Nichols as Jenny

- Jerry Orbach as Jack Rosenthal

- Sam Waterston as Ben

- Martin S. Bergmann as Prof. Louis Levy

- Daryl Hannah (uncredited) as Lisa Crosley

Production

After viewing the first cut of the film, Allen decided to throw out the first act, call back actors for reshoots, and focus on what turned out to be the central story.[4]

Music

Allen makes use of classical and jazz music in many of the film's scenes. The soundtrack includes Franz Schubert's String Quartet No. 15 (a recording by the Juilliard String Quartet), which is used in the scenes leading up to Dolores' death, and Judah discovering her body.

Influences

The outline of Judah's moral dilemma - whether a person can continue everyday life with the knowledge of having committed murder - evokes[5] the pivotal idea of Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment (1866), despite suggesting a resolution nearly opposite to that of the novel. Allen would revisit the theme in his films Match Point, Cassandra's Dream and Irrational Man. The characters of both Judah and his gangster brother have been said to be influenced by a Jewish medical student who attended NYU with one of Marshall Brickman's relatives.

Reception

Box office

The film grossed a domestic total of $18,254,702.[2]

Critical response

Crimes and Misdemeanors received mostly positive reviews. It currently holds a 93% "Certified Fresh" rating on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 42 critics, with an average rating of 8/10.[6] It also holds a 77/100 weighted average score on Metacritic, based on 10 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[7]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times lauded the film, remarking:

| “ | The wonder of Crimes and Misdemeanors is the facility with which Mr. Allen deals with so many interlocking stories of so many differing tones and voices. The film cuts back and forth between parallel incidents and between present and past with the effortlessness of a hip, contemporary Aesop. The movie's secret strength - its structure, really - comes from the truth of the dozens and dozens of particular details through which it arrives at its own very hesitant, not especially comforting, very moving generality."[8] | ” |

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four out of four stars, writing:

| “ | The movie generates the best kind of suspense, because it's not about what will happen to people - it's about what decisions they will reach. We have the same information they have. What would we do? How far would we go to protect our happiness and reputation? How selfish would we be? Is our comfort worth more than another person's life? Allen does not evade this question, and his answer seems to be, yes, for some people, it would be.[9] | ” |

Though normally an ardent critic of Allen's work, John Simon of National Review declared the film to be "Allen's first successful blending of drama and comedy, plot and subplot," and also wrote:

| “ | The chief strength of the movie is its courage in confronting grave and painful questions of the kind the American cinema has been doing its damnedest to avoid.[10] | ” |

Variety gave the film a more mixed review, however, writing, "Woody Allen ambitiously mixes his two favoured strains of cinema, melodrama and comedy, with mixed results in Crimes and Misdemeanours."[11]

In 2016, film critics Robbie Collin and Tim Robey ranked it as the second best movie by Woody Allen.[12]

Accolades

The film was met with critical acclaim, and was nominated for three Academy Awards: Woody Allen for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay, and Martin Landau for Best Actor in a Supporting Role.

In Empire magazine's poll of the 500 greatest movies of all time, Crimes and Misdemeanors was ranked number 267.[13] In 2010, it was the first film to win the 20/20 Award[14] for Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay (Woody Allen), and Best Supporting Actor (Martin Landau). It also received three additional nominations, for Best Director (Woody Allen), Best Supporting Actor (Jerry Orbach) and Best Supporting Actress (Anjelica Huston). In a 2016 Time Out contributors' poll, it ranked second only to Annie Hall among Allen's efforts, with Dave Calhoun praising it as "the film in which Woody's comic and serious sides most comfortably align".[15] The film achieved the same rank in an article by The Daily Telegraph critics Robbie Collin and Tim Robey, who wrote, "Here [Allen is] thinking deeply about moral choice, the question of whether guilt in your own eyes or the eyes of the world matters more. This bubblingly wise film, rich with beautifully dovetailing metaphors about blindness and conscience and the perils of self-knowledge, [...] is Allen on soaring form, gliding so elegantly through its maze of ideas it's as if the spirit of Fred Astaire gave it lift-off."[16] Crimes and Misdemeanors was also named Allen's second best by Chris Nashawaty of Entertainment Weekly[17] and Barbara VanDenbergh of The Arizona Republic,[18] third by Darian Lusk of CBS,[19] and fourth by Zachary Wigon of Nerve.[20] In a 2015 BBC critics' poll, it was voted the 57th greatest American film ever made.[21]

In October 2013, the film was voted by The Guardian readers as the third best film directed by Woody Allen.[22]

Release

Home media

Crimes and Misdemeanors was released through MGM Home Entertainment on DVD on June 5, 2001. A limited edition Blu-ray of 3,000 units was later released by Twilight Time on February 11, 2014.[23]

Further reading

- Litch, Mary M. (2010) [1st ed. 2002]. "9. EXISTENTIALISM - The Seventh Seal (1957), Crimes and Misdemeanors (1988), and Leaving Las Vegas (1995) [pp. 209-226]". Philosophy Through Film (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0415938759. ISBN 978-0-20386-332-9.

References

- ↑ "Crimes and Misdemeanors (15)". British Board of Film Classification. December 6, 1989. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- 1 2 Crimes and Misdemeanors at Box Office Mojo

- ↑ "In the Shadow of Moloch", New York Times Book Review, 98, p. 43, 1993, retrieved March 27, 2012

- ↑ "2046". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ Mary P. Nichols, Reconstructing Woody: Art, Love, and Life in the Films of Woody Allen (Rowman and Littlefield, 2000) ISBN 978-0-8476-8990-3, pp 149-164 (Part 10 The Ophthalmologist and the Filmmaker)

- ↑ Crimes and Misdemeanors at Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ Crimes and Misdemeanors at Metacritic

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (October 13, 1989). "Review/Film; 'Crimes and Misdemeanors,' New From Woody Allen". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (October 13, 1989). "Crimes and Misdemeanors". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ↑ Simon, John (December 8, 1989). "And Justice for None: Review of Crimes and Misdemeanors". National Review: 46–48.

- ↑ "Review: 'Crimes and Misdemeanors'". Variety. December 31, 1988. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ↑ "All 47 Woody Allen movies - ranked from worst to best". The Telegraph. October 12, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ↑ Empire Online

- ↑ 20/20 Award

- ↑ Editors, The (March 24, 2016). "The best Woody Allen movies of all time". Time Out. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ↑ Collin, Robbie; Robey, Tim (October 12, 2016). "All 47 Woody Allen movies - ranked from worst to best". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ↑ Nashawaty, Chris (July 18, 2016). "Woody Allen Films, Ranked". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ VanDenbergh, Barbara (July 29, 2014). "Woody Allen's top 10 best films". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Lusk, Darian (August 7, 2013). "Top 10 Woody Allen movies". CBS. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Wigon, Zachary. "Ranked: woody Allen Films from Worst to Best". Nerve. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ "The 100 greatest American films". BBC. July 20, 2015. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ↑ "The 10 best Woody Allen films". The Guardian. October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Crimes And Misdemeanors (1989) (Blu-Ray)". Screen Archives Entertainment. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Crimes and Misdemeanors |