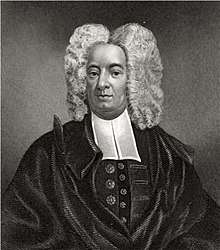

Cotton Mather

| The Reverend Cotton Mather FRS | |

|---|---|

Mather, c. 1700 | |

| Born |

February 12, 1663 Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Died |

February 13, 1728 (aged 65) Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Alma mater | Harvard College |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Parent(s) | Increase Mather and Maria Cotton |

| Relatives |

John Cotton (maternal grandfather) Richard Mather (paternal grandfather) |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Cotton Mather FRS (February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728; A.B. 1678, Harvard College; A.M. 1681, honorary doctorate 1710, University of Glasgow) was a socially and politically influential New England Puritan minister, prolific author, and pamphleteer. He left a scientific legacy due to his hybridization experiments and his promotion of inoculation for disease prevention, though he is most frequently remembered today for his involvement in the Salem witch trials. He was subsequently denied the presidency of Harvard College which his father, Increase Mather, had held.

Life and work

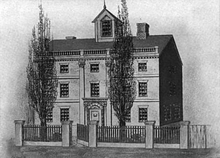

Mather was born in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, the son of Maria (née Cotton) and Increase Mather, and grandson of both John Cotton and Richard Mather, all also prominent Puritan ministers. Mather was named after his maternal grandfather John Cotton. He attended Boston Latin School, where his name was posthumously added to its Hall of Fame, and graduated from Harvard in 1678 at age 15. After completing his post-graduate work, he joined his father as assistant pastor of Boston's original North Church (not to be confused with the Anglican/Episcopal Old North Church of Paul Revere fame). In 1685, Mather assumed full responsibilities as pastor of the church.[1]:8

Mather wrote more than 450 books and pamphlets, and his ubiquitous literary works made him one of the most influential religious leaders in America. He set the moral tone in the colonies, and sounded the call for second- and third-generation Puritans to return to the theological roots of Puritanism, whose parents had left England for the New England colonies of North America. The most important of these was Magnalia Christi Americana (1702) which comprises seven distinct books, many of which depict biographical and historical narratives.

Mather influenced early American science. In 1716, he conducted one of the first recorded experiments with plant hybridization because of observations of corn varieties. This observation was memorialized in a letter to his friend James Petiver:[3]

First: my Friend planted a Row of Indian corn that was Coloured Red and Blue; the rest of the Field being planted with corn of the yellow, which is the most usual color. To the Windward side, this Red and Blue Row, so infected Three or Four whole Rows, as to communicate the same Colour unto them; and part of ye Fifth and some of ye Sixth. But to the Leeward Side, no less than Seven or Eight Rows, had ye same Colour communicated unto them; and some small Impressions were made on those that were yet further off.[4]

In November 1713, Mather's wife, newborn twins, and two-year-old daughter all succumbed during a measles epidemic.[5] He was twice widowed, and only two of his 15 children survived him; he died on the day after his 65th birthday and was buried on Copp's Hill, near Old North Church.[1]:40

Boyle's influence on Mather

Robert Boyle was a huge influence throughout Mather's career. He read Boyle's The Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy closely throughout the 1680s, and his own early works on science and religion borrowed greatly from it, using almost identical language to Boyle.[6]

Increase Mather

Mather's relationship with his father Increase Mather is thought by some to have been strained and difficult. Increase was a pastor of the North Square Church and president of Harvard College; he led an accomplished life. Despite Cotton's efforts, he never became quite as well known and successful in politics as his father. He did surpass his father's output as a writer, writing more than 400 books. One of the most public displays of their strained relationship emerged during the witch trials, which Increase Mather reportedly did not support.[7]

Yale College

Cotton Mather helped convince Elihu Yale to make a donation to a new college in New Haven which became Yale College.[8]

Salem witch trials of 1692, the Mather influence

Pre-trials

In 1689, Mather published Memorable Providences detailing the supposed afflictions of several children in the Goodwin family in Boston. Catholic washerwoman Goody Glover was convicted of witchcraft and executed in this case.[9] Mather had a prominent role in this case. Besides praying for the children, which also included fasting and meditation, he would also observe and record their activities. The children were subject to hysterical fits, which he detailed in Memorable Providences.[10] In his book, Mather argued that since there are witches and devils, there are "immortal souls." He also claimed that witches appear spectrally as themselves.[11] He opposed any natural explanations for the fits, he believed that people who confessed to using witchcraft were sane, he warned against performing magic due to its connection with the devil and he argued that spectral evidence should not be used as evidence for witchcraft.[12] Robert Calef was a contemporary of Mather and critical of him, and he considered this book responsible for laying the groundwork for the Salem witch trials three years later:

Mr Cotton Mather, was the most active and forward of any Minister in the Country in those matters, taking home one of the Children, and managing such Intreagues with that Child, and after printing such an account of the whole, in his Memorable Providences, as conduced much to the kindling of those Flames, that in Sir Williams time threatened the devouring of this Country.[13]

Nineteenth-century historian Charles Wentworth Upham shared the view that the afflicted in Salem were imitating the Goodwin children, but he put the blame on both Cotton and his father Increase Mather:

They are answerable… more than almost any other men have been, for the opinions of their time. It was, indeed a superstitious age; but made much more so by their operations, influence, and writings, beginning with Increase Mather's movement, at the assembly of Ministers, in 1681, and ending with Cotton Mather's dealings with the Goodwin children, and the account thereof which he printed and circulated far and wide. For this reason, then in the first place, I hold those two men responsible for what is called 'Salem Witchcraft'[14]

The court

Mather was influential in the construction of the court for the trials from the beginning. Sir William Phips, governor of the newly chartered Province of Massachusetts Bay, appointed his lieutenant governor, William Stoughton, as head of a special witchcraft tribunal and then as chief justice of the colonial courts, where he presided over the witch trials. According to George Bancroft, Mather had been influential in gaining the politically unpopular Stoughton his appointment as lieutenant governor under Phips through the intervention of Mather's own politically powerful father, Increase. "Intercession had been made by Cotton Mather for the advancement of Stoughton, a man of cold affections, proud, self-willed and covetous of distinction."[15] Apparently Mather saw in Stoughton, a bachelor who had never wed, an ally for church-related matters. Bancroft quotes Mather's reaction to Stoughton's appointment as follows:

"The time for a favor is come", exulted Cotton Mather; "Yea, the set time is come."[16]

Mather claimed not to have attended the trials in Salem (although his father attended the trial of George Burroughs). His contemporaries Calef and Thomas Brattle place him at the executions (see below). Mather began to publicize and celebrate the trials well before they were put to an end: "If in the midst of the many Dissatisfaction among us, the publication of these Trials may promote such a pious Thankfulness unto God, for Justice being so far executed among us, I shall Re-joyce that God is Glorified." Mather called himself a historian not an advocate but, according to one modern writer, his writing largely presumes the guilt of the accused and includes such comments as calling Martha Carrier "a rampant hag". Mather referred to George Burroughs[17] as a "very puny man" whose "tergiversations, contradictions, and falsehoods" made his testimony not "worth considering".[18][19]

Caution on the use of spectral evidence

The afflicted girls claimed that the semblance of a defendant, invisible to any but themselves, was tormenting them; this was considered evidence of witchcraft, despite the defendant's denial and profession of strongly held Christian beliefs. On May 31, 1692, Mather wrote to one of the judges, John Richards, a member of his congregation,[20] expressing his support of the prosecutions, but cautioning; "do not lay more stress on pure spectral evidence than it will bear … It is very certain that the Devils have sometimes represented the Shapes of persons not only innocent, but also very virtuous. Though I believe that the just God then ordinarily provides a way for the speedy vindication of the persons thus abused."[21]

An opinion on the matter was sought from the ministers of the area and a response was submitted June 15, 1692. Cotton Mather seems to take credit for the varied responses when anonymously celebrating himself years later: "drawn up at their desire, by Cotton Mather the younger, as I have been informed."[22] The "Return of the Several Ministers" ambivalently discussed whether or not to allow spectral evidence. The original full version of the letter was reprinted in late 1692 in the final two pages of Increase Mather's Cases of Conscience. It is a curious document and remains a source of confusion and argument. Calef calls it "perfectly Ambidexter, giving as great as greater Encouragement to proceed in those dark methods, then cautions against them… indeed the Advice then given, looks most like a thing of his Composing, as carrying both Fire to increase and Water to quench the Conflagration."[23][24] It seems likely that the "Several" ministers consulted did not agree, and thus Cotton Mather's construction and presentation of the advice could have been crucial to its interpretation.

Thomas Hutchinson summarized the Return, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before." Reprinting the Return five years later in his anonymously published Life of Phips (1697), Cotton Mather omitted the fateful "two first and the last" sections, though they were the ones he had already given most attention in his "Wonders of the Invisible World" rushed into publication in the summer and early autumn of 1692.

On August 19, 1692, Mather attended the execution of George Burroughs[25] (and four others who were executed after Mather spoke) and Robert Calef presents him as playing a direct and influential role:

Mr. Buroughs [sic] was carried in a Cart with others, through the streets of Salem, to Execution. When he was upon the Ladder, he made a speech for the clearing of his Innocency, with such Solemn and Serious Expressions as were to the Admiration of all present; his Prayer (which he concluded by repeating the Lord's Prayer) [as witches were not supposed to be able to recite] was so well worded, and uttered with such composedness as such fervency of spirit, as was very Affecting, and drew Tears from many, so that if seemed to some that the spectators would hinder the execution. The accusers said the black Man [Devil] stood and dictated to him. As soon as he was turned off [hanged], Mr. Cotton Mather, being mounted upon a Horse, addressed himself to the People, partly to declare that he [Mr. Burroughs] was no ordained Minister, partly to possess the People of his guilt, saying that the devil often had been transformed into the Angel of Light. And this did somewhat appease the People, and the Executions went on; when he [Mr. Burroughs] was cut down, he was dragged by a Halter to a Hole, or Grave, between the Rocks, about two feet deep; his Shirt and Breeches being pulled off, and an old pair of Trousers of one Executed put on his lower parts: he was so put in, together with [John] Willard and [Martha] Carrier, that one of his Hands, and his Chin, and a Foot of one of them, was left uncovered.

On September 2, 1692, after eleven of the accused had been executed, Cotton Mather wrote a letter to Chief Justice William Stoughton congratulating him on "extinguishing of as wonderful a piece of devilism as has been seen in the world" and claiming that "one half of my endeavors to serve you have not been told or seen."

Regarding spectral evidence, Upham concludes that "Cotton Mather never in any public writing 'denounced the admission' of it, never advised its absolute exclusion; but on the contrary recognized it as a ground of 'presumption' … [and once admitted] nothing could stand against it. Character, reason, common sense, were swept away."[26] In a letter to an English clergyman in 1692, Boston intellectual Thomas Brattle, criticizing the trials, said of the judges' use of spectral evidence:

The S.G. [Salem Gentlemen] will by no means allow, that any are brought in guilty, and condemned, by virtue of spectre Evidence... but whether it is not purely by virtue of these spectre evidences, that these persons are found guilty, (considering what before has been said,) I leave you, and any man of sense, to judge and determine.[27]

The later exclusion of spectral evidence from trials by Governor Phips, around the same time his own wife's (Lady Mary Phips) name coincidentally started being bandied about in connection with witchcraft, began in January 1693. This immediately brought about a sharp decrease in convictions. Due to a reprieve by Phips, there were no further executions. Phips's actions were vigorously opposed by William Stoughton.[26]

Bancroft notes that Mather considered witches "among the poor, and vile, and ragged beggars upon Earth", and Bancroft asserts that Mather considered the people against the witch trials to be witch advocates.[28]

Post-trials

In the years after the trials, of the principal actors in the trial, whose lives are recorded after, neither he nor Stoughton admitted strong misgivings.[29] For several years after the trials, Cotton Mather continued to defend them and seemed to hold out a hope for their return.[30]:67

Wonders of the Invisible World contained a few of Mather's sermons, the conditions of the colony and a description of witch trials in Europe.[31]:335 He somewhat clarified the contradictory advice he had given in Return of the Several Ministers, by defending the use of spectral evidence.[32] Wonders of the Invisible World appeared around the same time as Increase Mather's Cases of Conscience."[33]

Mather did not sign his name or support his father's book initially:

There are fourteen worthy ministers that have newly set their hands unto a book now in the press, containing Cases of Conscience about Witchcraft. I did, in my Conscience think, that as the humors of this people now run, such a discourse going alone would not only enable the witch-advocates, very learnedly to cavil and nibble at the late proceedings against the witches, considered in parcels, while things as they lay in bulk, with their whole dependencies, were not exposed; but also everlastingly stifle any further proceedings of justice & more than so produce a public & open contest with the judges who would (tho beyond the intention of the worthy author & subscribers) find themselves brought unto the bar before the rashest mobile [mob]

— October 20, 1692 letter to his uncle John Cotton.[34]

The last major events in Mather's involvement with witchcraft were his interactions with Mercy Short in December 1692 and Margaret Rule in September 1693.[35] The latter brought a five year campaign by Boston merchant Robert Calef against the influential and powerful Mathers.[33] Calef's book More Wonders of the Invisible World was inspired by the fear that Mather would succeed in once again stirring up new witchcraft trials, and the need to bear witness to the horrible experiences of 1692. He quotes the public apologies of the men on the jury and one of the judges. Increase Mather was said to have publicly burned Calef's book in Harvard Yard around the time he was removed from the head of the college and replaced by Samuel Willard.[36][37]

Poole vs. Upham

In 1869, William Frederick Poole quoted from various school textbooks of the time demonstrating they were in agreement on Cotton Mather's role in the Witch Trials:

If anyone imagines that we are stating the case too strongly, let him try an experiment with the first bright boy he meets by asking,...

'Who got up Salem Witchcraft?'... he will reply, 'Cotton Mather'. Let him try another boy...

'Who was Cotton Mather?' and the answer will come, 'The man who was on horseback, and hung witches.'[38]

Poole was a librarian, and a lover of literature, including Mather's Magnalia "and other books and tracts, numbering nearly 400 [which] were never so prized by collectors as today." Poole announced his intention to redeem Mather's name, using as a springboard a harsh critique of a recently published tome by Charles Wentworth Upham, Salem Witchcraft Volumes I and II With an Account of Salem Village and a History of Opinions on Witchcraft and Kindred Subjects, which runs to almost 1,000 pages, and a quick search of the name Mather (referring to either father, son, or ancestors) shows that it occurs 96 times. Poole's critique, in book form, runs less than 70 pages but the name "Mather" occurs many more times than the other book, which is more than ten times as long. Upham shows a balanced and complicated view of Cotton Mather, such as this first mention: "One of Cotton Mather's most characteristic productions is the tribute to his venerated master. It flows from a heart warm with gratitude."

Upham's book refers to Robert Calef no fewer than 25 times with the majority of these regarding documents compiled by Calef in the mid-1690s and stating: "Although zealously devoted to the work of exposing the enormities connected with the witchcraft prosecutions, there is no ground to dispute the veracity of Calef as to matters of fact." He goes on to say that Calef's collection of writings "gave a shock to Mather's influence, from which it never recovered."

Calef produced only the one book; he is self-effacing and apologetic for his limitations, and on the title page he is listed not as author but "collector". Poole, champion of literature, cannot accept Calef whose "faculties, as indicated by his writings appear to us to have been of an inferior order;…", and his book "in our opinion, has a reputation much beyond its merits." Poole refers to Calef as Mather's "personal enemy" and opens a line, "Without discussing the character and motives of Calef…" but does not follow up on this suggestive comment to discuss any actual or purported motive or reason to impugn Calef. Upham responded to Poole (referring to Poole as "the Reviewer") in a book running five times as long and sharing the same title but with the clauses reversed: Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather.Many of Poole's arguments were addressed, but both authors emphasize the importance of Cotton Mather's difficult and contradictory view on spectral evidence, as copied in the final pages, called "The Return of Several Ministers", of Increase Mather's "Cases of Conscience".[39]

The debate continues: Kittredge vs. Burr

Evidenced by the published opinion in the years that followed the Poole vs Upham debate, it would seem Upham was considered the clear winner (see Sibley, GH Moore, WC Ford, and GH Burr below.). In 1891, Harvard English professor Barrett Wendall wrote Cotton Mather, The Puritan Priest. His book often expresses agreement with Upham but also announces an intention to show Cotton Mather in a more positive light. "[Cotton Mather] gave utterance to many hasty things not always consistent with fact or with each other…" And some pages later: "[Robert] Calef’s temper was that of the rational Eighteenth century; the Mathers belonged rather to the Sixteenth, the age of passionate religious enthusiasm."

In 1907, George Lyman Kittredge published an essay that would become foundational to a major change in the 20th-century view of witchcraft and Mather culpability therein. Kittredge is dismissive of Robert Calef, and sarcastic toward Upham, but shows a fondness for Poole and a similar soft touch toward Cotton Mather. Responding to Kittredge in 1911, George Lincoln Burr, a historian at Cornell, published an essay that begins in a professional and friendly fashion toward both Poole and Kittredge, but quickly becomes a passionate and direct criticism, stating that Kittredge in the "zeal of his apology… reached results so startlingly new, so contradictory of what my own lifelong study in this field has seemed to teach, so unconfirmed by further research… and withal so much more generous to our ancestors than I can find it in my conscience to deem fair, that I should be less than honest did I not seize this earliest opportunity share with you the reasons for my doubts…"[40] (In referring to "ancestors" Burr primarily means the Mathers, as is made clear in the substance of the essay.) The final paragraph of Burr's 1911 essay pushes these men's debate into the realm of a progressive creed

… I fear that they who begin by excusing their ancestors may end by excusing themselves.[41]

Perhaps as a continuation of his argument, in 1914, George Lincoln Burr published a large compilation "Narratives". This book arguably continues to be the single most cited reference on the subject. Unlike Poole and Upham, Burr avoids forwarding his previous debate with Kittredge directly into his book and mentions Kittredge only once, briefly in a footnote citing both of their essays from 1907 and 1911, but without further comment.[42] But in addition to the viewpoint displayed by Burr's selections, he weighs in on the Poole vs Upham debate at various times, including siding with Upham in a note on Thomas Brattle's letter, "The strange suggestion of W. F. Poole that Brattle here means Cotton Mather himself, is adequately answered by Upham…"[43] Burr's "Narratives" reprint a lengthy but abridged portion of Calef's book and introducing it he digs deep into the historical record for information on Calef and concludes "…that he had else any grievance against the Mathers or their colleagues there is no reason to think." Burr finds that a comparison between Calef's work and original documents in the historical record collections "testify to the care and exactness…"[44]

20th century revision: The Kittredge lineage at Harvard

1920–3 Kenneth B. Murdock wrote a doctoral dissertation on Increase Mather advised by Chester Noyes Greenough and Kittredge. Murdock's father was a banker hired in 1920 to run the Harvard Press[45] and he published his son's dissertation as a handsome volume in 1925: Increase Mather, The Foremost American Puritan (Harvard University Press). Kittredge was right hand man to the elder Murdock at the Press.[46] This work focuses on Increase Mather and is more critical of the son, but the following year he published a selection of Cotton Mather's writings with an introduction that claims Cotton Mather was "not less but more humane than his contemporaries. Scholars have demonstrated that his advice to the witch judges was always that they should be more cautious in accepting evidence" against the accused.[47] Murdock's statement seems to claim a majority view. But one wonders who Murdock would have meant by "scholars" at this time other than Poole, Kittredge, and TJ Holmes (below)[48] and Murdock's obituary calls him a pioneer "in the reversal of a movement among historians of American culture to discredit the Puritan and colonial period…"[49]

1924 Thomas J. Holmes was an Englishman with no college education, but he apprenticed in bookbinding and emigrated to the U.S. and become the librarian at the William G. Mather Library in Ohio [50] where he likely met Murdock. In 1924, Holmes wrote an essay for the Bibliographical Society of America identifying himself as part of the Poole-Kittredge lineage and citing Kenneth B. Murdock's still unpublished dissertation. In 1932 Holmes published a bibliography of Increase Mather followed by Cotton Mather, A Bibliography (1940). Holmes often cites Murdock and Kittredge and is highly knowledgeable about the construction of books. Holmes' work also includes Cotton Mather’s October 20, 1692 letter (see above) to his uncle opposing an end to the trials.

1930 Samuel Eliot Morison published Builders of the Bay Colony. Morison chose not to include anyone with the surname Mather or Cotton in his collection of twelve "builders" and in the bibliography writes "I have a higher opinion than most historians of Cotton Mather's Magnalia… Although Mather is inaccurate, pedantic, and not above suppresio veri, he does succeed in giving a living picture of the person he writes about." Whereas Kittredge and Murdock worked from the English department, Morison was from Harvard's history department. Morison's view seems to have evolved over the course of the 1930s, as can be seen in Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century (1936) published while Kittredge ran the Harvard press, and in a year that coincided with the tercentary of the college: "Since the appearance of Professor Kittredge's work, it is not necessary to argue that a man of learning…" of that era should be judged on his view of witchcraft.[51] In The Intellectual Life of Colonial New England (1956), Morison writes that Cotton Mather found balance and level-thinking during the witchcraft trials. Like Poole, Morison suggests Calef had an agenda against Mather, without providing supporting evidence.[52]

1953 Perry Miller published The New England Mind: From Colony to Province (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press). Miller worked from the Harvard English Department and his expansive prose contains few citations, but the "Bibliographical Notes" for Chapter XIII "The Judgement of the Witches" references the bibliographies of TJ Holmes (above) calling Holmes portrayal of Cotton Mather's composition of Wonders "an epoch in the study of Salem Witchcraft." However, following the discovery of the authentic holograph of the September 2, 1692 letter, in 1985, David Levin writes that the letter demonstrates that the timeline employed by TJ Holmes and Perry Miller, is off by "three weeks." [53] Contrary to the evidence in the later arriving letter, Miller portrays Phips and Stoughton as pressuring Cotton Mather to write the book (p.201): "If ever there was a false book produced by a man whose heart was not in it, it is The Wonders….he was insecure, frightened, sick at heart…" The book "has ever since scarred his reputation," Perry Miller writes. Miller seems to imagine Cotton Mather as sensitive, tender, and a good vehicle for his jeremiad thesis: "His mind was bubbling with every sentence of the jeremiads, for he was heart and soul in the effort to reorganize them.

1969 Chadwick Hansen Witchcraft at Salem. Hansen states a purpose to "set the record straight" and reverse the "traditional interpretation of what happened at Salem…" and names Poole and Kittredge as like-minded influences. (Hansen reluctantly keys his footnotes to Burr's anthology for the reader's convenience, "in spite of [Burr's] anti-Puritan bias…") Hansen presents Mather as a positive influence on the Salem Trials and considers Mather's handling of the Goodwin children sane and temperate.[54] Hansen posits that Mather was a moderating influence by opposing the death penalty for those who confessed—or feigned confession—such as Tituba and Dorcas Good,[55] and that most negative impressions of him stem from his "defense" of the ongoing trials in Wonders of the Invisible World.[56] Writing an introduction to a facsimile of Robert Calef's book in 1972, Hansen compares Robert Calef to Joseph Goebbels, and also explains that, in Hansen's opinion, women "are more subject to hysteria than men."[57]

1971 The Admirable Cotton Mather by James Playsted Wood. A young adult book. In the preface, Wood discusses the Harvard-based revision and writes that Kittredge and Murdock "added to a better understanding of a vital and courageous man…"

1985 David Hall writes, "With [Kittredge] one great phase of interpretation came to a dead end."[58] Hall writes that whether the old interpretation favored by "antiquarians" had begun with the "malice of Robert Calef or deep hostility to Puritanism," either way "such notions are no longer… the concern of the historian." But David Hall notes "one minor exception. Debate continues on the attitude and role of Cotton Mather…"

Tercentary of the trials and ongoing scholarship

Toward the later half of the twentieth century, a number of historians at universities far from New England seemed to find inspiration in the Kittredge lineage. In Selected Letters of Cotton Mather Ken Silverman writes, "Actually, Mather had very little to do with the trials."[59] Twelve pages later Silverman publishes, for the first time, a letter to chief judge William Stoughton on September 2, 1692, in which Cotton Mather writes "… I hope I can may say that one half of my endeavors to serve you have not been told or seen … I have labored to divert the thoughts of my readers with something of a designed contrivance…"[60] Writing in the early 1980s, historian John Demos imputed to Mather a purportedly moderating influence on the trials.[61]:305

Coinciding with the tercentary of the trials in 1992, there was a flurry of publications.

Historian Larry Gregg highlights Mather's cloudy thinking and confusion between sympathy for the possessed, and the boundlessness of spectral evidence when Mather stated, "the devil have sometimes represented the shapes of persons not only innocent, but also the very virtuous."[62]:88

Smallpox inoculation controversy

The practice of smallpox inoculation (as opposed to the later practice of vaccination) was developed possibly in 8th-century India[63] or 10th-century China.[64] Spreading its reach in seventeenth-century Turkey, inoculation or, rather, variolation, involved infecting a person via a cut in the skin with exudate from a patient with a relatively mild case of smallpox (variola), to bring about a manageable and recoverable infection that would provide later immunity. By the beginning of the 18th century, the Royal Society in England was discussing the practice of inoculation, and the smallpox epidemic in 1713 spurred further interest.[65] It was not until 1721, however, that England recorded its first case of inoculation.[66]

Early New England

Smallpox was a serious threat in colonial America, most devastating to Native Americans, but also to Anglo-American settlers. New England suffered smallpox epidemics in 1677, 1689–90, and 1702.[67] It was highly contagious, and mortality could reach as high as 30 percent.[68] Boston had been plagued by smallpox outbreaks in 1690 and 1702. During this era, public authorities in Massachusetts dealt with the threat primarily by means of quarantine. Incoming ships were quarantined in Boston harbor, and any smallpox patients in town were held under guard or in a "pesthouse".[69]

In 1706, Mather's slave, Onesimus, explained to Mather how he had been inoculated as a child in Africa.[70] Mather was fascinated by the idea. By July 1716, he had read an endorsement of inoculation by Dr Emanuel Timonius of Constantinople in the Philosophical Transactions. Mather then declared, in a letter to Dr John Woodward of Gresham College in London, that he planned to press Boston's doctors to adopt the practice of inoculation should smallpox reach the colony again.[71]

By 1721, a whole generation of young Bostonians was vulnerable and memories of the last epidemic's horrors had by and large disappeared.[72] On April 22 of that year, the HMS Seahorse arrived from the West Indies carrying smallpox on board. Despite attempts to protect the town through quarantine, eight known cases of smallpox appeared in Boston by May 27, and by mid-June, the disease was spreading at an alarming rate. As a new wave of smallpox hit the area and continued to spread, many residents fled to outlying rural settlements. The combination of exodus, quarantine, and outside traders' fears disrupted business in the capital of the Bay Colony for weeks. Guards were stationed at the House of Representatives to keep Bostonians from entering without special permission. The death toll reached 101 in September, and the Selectmen, powerless to stop it, "severely limited the length of time funeral bells could toll."[73] As one response, legislators delegated a thousand pounds from the treasury to help the people who, under these conditions, could no longer support their families.

On June 6, 1721, Mather sent an abstract of reports on inoculation by Timonius and Jacobus Pylarinus to local physicians, urging them to consult about the matter. He received no response. Next, Mather pleaded his case to Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, who tried the procedure on his youngest son and two slaves—one grown and one a boy. All recovered in about a week. Boylston inoculated seven more people by mid-July. The epidemic peaked in October 1721, with 411 deaths; by February 26, 1722, Boston was again free from smallpox. The total number of cases since April 1721 came to 5,889, with 844 deaths—more than three-quarters of all the deaths in Boston during 1721.[74] Meanwhile, Boylston had inoculated 287 people, with six resulting deaths.[75]

Inoculation debate

Boylston and Mather's inoculation crusade "raised a horrid Clamour"[76] among the people of Boston. Both Boylston and Mather were "Object[s] of their Fury; their furious Obloquies and Invectives", which Mather acknowledges in his diary. Boston's Selectmen, consulting a doctor who claimed that the practice caused many deaths and only spread the infection, forbade Boylston from performing it again.[77]

The New-England Courant published writers who opposed the practice. The editorial stance was that the Boston populace feared that inoculation spread, rather than prevented, the disease; however, some historians, notably H. W. Brands, have argued that this position was a result of the contrarian positions of editor-in-chief James Franklin (a brother of Benjamin Franklin).[78] Public discourse ranged in tone from organized arguments by John Williams from Boston, who posted that "several arguments proving that inoculating the smallpox is not contained in the law of Physick, either natural or divine, and therefore unlawful",[79] to those put forth in a pamphlet by Dr. William Douglass of Boston, entitled The Abuses and Scandals of Some Late Pamphlets in Favour of Inoculation of the Small Pox (1721), on the qualifications of inoculation's proponents. (Douglass was exceptional at the time for holding a medical degree from Europe.) At the extreme, in November 1721, someone hurled a lighted grenade into Mather's home.[80][81]

Medical opposition

Several opponents of smallpox inoculation, among them John Williams, stated that there were only two laws of physick (medicine): sympathy and antipathy. In his estimation, inoculation was neither a sympathy toward a wound or a disease, or an antipathy toward one, but the creation of one. For this reason, its practice violated the natural laws of medicine, transforming health care practitioners into those who harm rather than heal.[82]

As with most colonists, Williams' Puritan beliefs were enmeshed in every aspect of his life, and he used the Bible to state his case. He quoted Matthew 9:12, when Jesus said: "It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick." Dr. William Douglass proposed a more secular argument against inoculation, stressing the importance of reason over passion and urging the public to be pragmatic in their choices. In addition, he demanded that ministers leave the practice of medicine to physicians, and not meddle in areas where they lacked expertise. According to Douglass, smallpox inoculation was "a medical experiment of consequence," one not to be undertaken lightly. He believed that not all learned individuals were qualified to doctor others, and while ministers took on several roles in the early years of the colony, including that of caring for the sick, they were now expected to stay out of state and civil affairs. Douglass felt that inoculation caused more deaths than it prevented. The only reason Mather had had success in it, he said, was because Mather had used it on children, who are naturally more resilient. Douglass vowed to always speak out against "the wickedness of spreading infection".[83] Speak out he did: "The battle between these two prestigious adversaries [Douglass and Mather] lasted far longer than the epidemic itself, and the literature accompanying the controversy was both vast and venomous."[84]

Puritan resistance

Generally, Puritan pastors favored the inoculation experiments. Increase Mather, Cotton's father, was joined by prominent pastors Benjamin Colman and William Cooper in openly propagating the use of inoculations.[85] "One of the classic assumptions of the Puritan mind was that the will of God was to be discerned in nature as well as in revelation."[86] Nevertheless, Williams questioned whether the smallpox "is not one of the strange works of God; and whether inoculation of it be not a fighting with the most High." He also asked his readers if the smallpox epidemic may have been given to them by God as "punishment for sin," and warned that attempting to shield themselves from God's fury (via inoculation), would only serve to "provoke him more".[87]

Puritans found meaning in affliction, and they did not yet know why God was showing them disfavor through smallpox. Not to address their errant ways before attempting a cure could set them back in their "errand". Many Puritans believed that creating a wound and inserting poison was doing violence and therefore was antithetical to the healing art. They grappled with adhering to the Ten Commandments, with being proper church members and good caring neighbors. The apparent contradiction between harming or murdering a neighbor through inoculation and the Sixth Commandment—"thou shalt not kill"—seemed insoluble and hence stood as one of the main objections against the procedure. Williams maintained that because the subject of inoculation could not be found in the Bible, it was not the will of God, and therefore "unlawful."[88] He explained that inoculation violated The Golden Rule, because if one neighbor voluntarily infected another with disease, he was not doing unto others as he would have done to him. With the Bible as the Puritans' source for all decision-making, lack of scriptural evidence concerned many, and Williams vocally scorned Mather for not being able to reference an inoculation edict directly from the Bible.[89]

Inoculation defended

With the smallpox epidemic catching speed and racking up a staggering death toll, a solution to the crisis was becoming more urgently needed by the day. The use of quarantine and various other efforts, such as balancing the body's humors, did not slow the spread of the disease. As news rolled in from town to town and correspondence arrived from overseas, reports of horrific stories of suffering and loss due to smallpox stirred mass panic among the people. "By circa 1700, smallpox had become among the most devastating of epidemic diseases circulating in the Atlantic world."[90]

Mather strongly challenged the perception that inoculation was against the will of God and argued the procedure was not outside of Puritan principles. He wrote that "whether a Christian may not employ this Medicine (let the matter of it be what it will) and humbly give Thanks to God's good Providence in discovering of it to a miserable World; and humbly look up to His Good Providence (as we do in the use of any other Medicine) It may seem strange, that any wise Christian cannot answer it. And how strangely do Men that call themselves Physicians betray their Anatomy, and their Philosophy, as well as their Divinity in their invectives against this Practice?"[91] The Puritan minister began to embrace the sentiment that smallpox was an inevitability for anyone, both the good and the wicked, yet God had provided them with the means to save themselves. Mather reported that, from his view, "none that have used it ever died of the Small Pox, tho at the same time, it were so malignant, that at least half the People died, that were infected With it in the Common way."[92]

While Mather was experimenting with the procedure, prominent Puritan pastors Benjamin Colman and William Cooper expressed public and theological support for them.[93] The practice of smallpox inoculation was eventually accepted by the general population due to first-hand experiences and personal relationships. Although many were initially wary of the concept, it was because people were able to witness the procedure's consistently positive results, within their own community of ordinary citizens, that it became widely utilized and supported. One important change in the practice after 1721 was regulated quarantine of innoculees.[94]

The aftermath

Although Mather and Boylston were able to demonstrate the efficacy of the practice, the debate over inoculation would continue even beyond the epidemic of 1721–22. After overcoming considerable difficulty and achieving notable success, Boylston traveled to London in 1725, where he published his results and was elected to the Royal Society in 1726, with Mather formally receiving the honor two years prior.[95]

Sermons against Pirates and Piracy

Throughout his career Mather was also keen to minister to convicted pirates.[96] He produced a number of pamphlets and sermons concerning piracy, including “Faithful Warnings to prevent Fearful Judgments,” “Instructions to the Living, from the Condition of the Dead,” “The Converted Sinner ... A Sermon Preached in Boston, May 31, 1724, In the Hearing and at the Desire of certain Pirates,” “A Brief Discourse occasioned by a Tragical Spectacle of a Number of Miserables under Sentence of Death for Piracy,” “Useful Remarks. An Essay upon Remarkables in the Way of Wicked Men,” and “The Vial Poured Out Upon the Sea”. His father Increase had preached at the trial of Dutch pirate Peter Roderigo[97]; Cotton Mather in turn preached at the trials and sometimes executions of pirate Captains (or the crews of) William Fly, John Quelch, Samuel Bellamy, William Kidd, Charles Harris, and John Phillips. He also ministered to Thomas Hawkins, Thomas Pound, and William Coward; having been convicted of piracy, they were jailed alongside “Mary Glover the Irish Catholic witch,” daughter of witch “Goody” Ann Glover at whose trial Mather had also preached.[98]

In his conversations with William Fly and his crew Mather scolded them: “You have something within you, that will compell you to confess, That the Things which you have done, are most Unreasonable and Abominable. The Robberies and Piracies, you have committed, you can say nothing to Justify them. … It is a most hideous Article in the Heap of Guilt lying on you, that an Horrible Murder is charged upon you; There is a cry of Blood going up to Heaven against you.”[99]

Works

- Major

- Boston Ephermeris (1686)

- Ornaments for the Daughters of Zion (1692)

- Wonders of the Invisible World (1693)

- The Biblia Americana (1693–1728)

- Decennium Luctuosom: a History of the Long War (1699)

- Pillars of Salt (1699)

- Magnalia Christi Americana (1702)

- The Negro Christianized (1706)

- Corderius Americanus: A Discourse on the Good Education of Children (1708)

- Bonifacius (1710)

- Theopolis Americana: An Essay on the Golden Street of the Holy City (1710)

- The Christian Philosopher (1721)

- Manductio ad Ministerium (1726)

Boston Ephemeris

The Boston Ephemeris was an almanac written by Mather in 1686. The content was similar to what is known today as the Farmer's Almanac. This was particularly important because it shows that Cotton Mather had influence in mathematics during the time of Puritan New England. This almanac contained a significant amount of astronomy, celestial within the text of the almanac the positions and motions of these celestial bodies, which he must have calculated by hand.[100]

The Biblia Americana

When Mather died, he left behind an abundance of unfinished writings, including one entitled The Biblia Americana. Mather believed that Biblia Americana was the best thing he had ever written; his masterwork.[101] Biblia Americana contained Mather's thoughts and opinions on the Bible and how he interpreted it. Biblia Americana is incredibly large, and Mather worked on it from 1693 until 1728, when he died. Mather tried to convince others that philosophy and science could work together with religion instead of against it. People did not have to choose one or the other. In Biblia Americana, Mather looked at the Bible through a scientific perspective, completely opposite to his perspective in The Christian Philosopher, in which he approached science in a religious manner.[102]

Pillars of Salt

Mather's first published sermon, printed in 1686, concerned the execution of James Morgan, convicted of murder. Thirteen years later, Mather published the sermon in a compilation, along with other similar works, called Pillars of Salt.[103]

Magnalia Christi Americana

Magnalia Christi Americana, considered Mather's greatest work, was published in 1702, when he was 39. The book includes several biographies of saints and describes the process of the New England settlement.[104] In this context "saints" does not refer to the canonized saints of the Catholic church, but to those Puritan divines about whom Mather is writing. It comprises seven total books, including Pietas in Patriam: The life of His Excellency Sir William Phips, originally published anonymously in London in 1697. Despite being one of Mather's best-known works, some have openly criticized it, labeling it as hard to follow and understand, and poorly paced and organized. However, other critics have praised Mather's work, citing it as one of the best efforts at properly documenting the establishment of America and growth of the people.[105]

The Christian Philosopher

In 1721, Mather published The Christian Philosopher, the first systematic book on science published in America. Mather attempted to show how Newtonian science and religion were in harmony. It was in part based on Robert Boyle's The Christian Virtuoso (1690). Mather reportedly took inspiration from Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, by the 12th-century Islamic philosopher Abu Bakr Ibn Tufail.

Despite condemning the "Mahometans" as infidels, Mather viewed the novel's protagonist, Hayy, as a model for his ideal Christian philosopher and monotheistic scientist. Mather viewed Hayy as a noble savage and applied this in the context of attempting to understand the Native American Indians, in order to convert them to Puritan Christianity. Mather's short treatise on the Lord's Supper was later translated by his nephew Josiah Cotton.[106]

Bibliography

- Mather, Cotton (2001) [1689], A Family, Well-Ordered .

- ——— (1911–1912), Diary, Collections, vii–viii (vii), Massachusetts Historical Society .

- ——— (1995), Smolinski, Reiner, ed., The Threefold Paradise of Cotton Mather: An Edition of 'Triparadisus', Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-1519-2 .

- ——— (2010), Smolinski, Reiner, ed., Biblia Americana (edited, with an introduction and annotations), 1: Genesis, Grand Rapids and Tuebingen: Baker Academic and Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 978-0-8010-3900-3 .

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Sibley, John Langdon (1885). Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Volume III. Cambridge: Charles William Sever, University Bookstore.

- ↑ Forty of Boston's historic houses, State Street Trust Co, 1912 .

- ↑ Zirkle 1935, p. 104

- ↑ Zirkle 1935, p. 105

- ↑ Hostetter, Margaret Kendrick (April 5, 2012). "What We Don't See". The New England Journal of Medicine. 366: 1328–34. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1111421. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ↑ Middlekauff, Robert (1999), The Mathers: Three Generations of Puritan Intellectuals, 1596–1728, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press .

- ↑ Hovey, pp. 531–32

- ↑ Profile, Yale University, archived from the original on April 8, 2009, retrieved December 25, 2014 .

- ↑ Mather, Cotton (1689), Memorable Providences, Boston: Joseph Brunning

- ↑ Werking, Richard H (1972). ""Reformation Is Our Only Preservation": Cotton Mather and Salem Witchcraft". The William and Mary Quarterly. 29: 283.

- ↑ Ronan, John (2012). ""Young Goodman Brown" and the Mathers". The New England Quarterly. 85: 264–265. doi:10.1162/tneq_a_00186.

- ↑ Harley, David (1996). "Explaining Salem: Calvinist Psychology and the Diagnosis of Possession". The American Historical Review. 101: 315–316. doi:10.2307/2170393.

- ↑ Calef, Robert (1700), More Wonders of the Invisible World, London, UK: Nath Hillar on London Bridge, p. 152

- ↑ Upham, Charles Wentworth (September 1869). "Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather". The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History and Biography of America. Second. Vol. VI no. 3. Morrisania, NY: Henry B. Dawson. p. 140. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- ↑ Bancroft 1874–1878, p. 83.

- ↑ Bancroft 1874–1878, p. 84.

- ↑ Burroughs was a Harvard alumnus who survived Indian attacks in Maine. He was an unordained minister hanged the same day as Martha Carrier, John Proctor, George Jacobs, and John Willard

- ↑ Stacy Schiff. "The Witches of Salem: Diabolical doings in a Puritan village", The New Yorker, September 7, 2015, pp. 46-55.

- ↑ Wonders of the Invisible World .

- ↑ Upham 1869.

- ↑ Mather, Cotton (1971). Silverman, Kenneth, ed. Selected Letters. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 35–40. ISBN 0-8071-0920-7.

- ↑ Anonymous (1697), The Life of Sir William Phips, London, UK .

- ↑ Upham 1859.

- ↑ Calef 1823, pp. 301–03.

- ↑ Three independent contemporary sources place him there: Thomas Brattle, Samuel Sewall, and Robert Calef. Brattle refers to him "C.M." in Burr Narratives (Scribner, 1914) p. 177. Calef's account is also reprinted in Burr "Narratives" p. 360. Diary of Samuel Sewall (MHS, Boston, 1878) p. 363

- 1 2 Upham, Charles (1859), Salem Witchcraft, New York: Frederick Ungar, ISBN 0-548-15034-6 .

- ↑ Burr, George Lincoln. Narrative of Witchcraft Cases 1648–1706. University of Virginia Library: Electronic Text Center.

- ↑ Bancroft 1874–1878, p. 85.

- ↑ Bancroft 1874–1878, p. 98.

- ↑ Levy, Babette (1979). Cotton Mather. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-7261-8.

- ↑ Craker, Wendel D. (1997), "Spectral Evidence, Non-Spectral acts of Witchcraft, and Confessions at Salem in 1692", The Historical Journal, 40 (2)

- ↑ Hansen 1969, p. 209.

- 1 2 Breslaw 2000, p. 455.

- ↑ Holmes, Thomas James (1974), Cotton Mather: A Bibliography of His Works, Crofton .

- ↑ Lovelace 1979, p. 202.

- ↑ MHS secretary John Eliot seems to be the first to make this claim in "Biographical Dictionary" (Boston and Salem, 1809) PD available online. p 95-6.

- ↑ Lovelace 1979, p. 22.

- ↑ Poole, William Frederick (1869). Cotton Mather and Salem Witchcraft. Cambridge: University Press: Welch, Bigelow, & Co. p. 67.

- ↑ Mather, Witchcraft, University of Virginia .

- ↑ GL Burr, England's Place in the History of Witchcraft" AAS, pp 4-5. These page numbers refer to original book format, available PD online. Also see link to PDF from AAS.

- ↑ GL Burr, NE Place in Witchcraft, 1911, p 35.

- ↑ Burr, George Lincoln. Narrative of Witchcraft Cases 1648–1706. PD available online. p xxi footnote 1.

- ↑ Burr, George Lincoln. Narrative of Witchcraft Cases 1648–1706. PD available online. p 188 footnote 3.

- ↑ Burr, George Lincoln. Narrative of Witchcraft Cases 1648–1706. PD available online. p 293.

- ↑ Max Hall Harvard University Press A History 1986 Harvard University Press Cambridge MA p 43, 61

- ↑ Max Hall Harvard University Press, p 43, 61.

- ↑ K Murdock Selections from Cotton Mather (Hafner, New York, 1926). See introduction.

- ↑ For contrast, see Herbert Schneider, of Columbia University, who in 1930 described the Mathers as "smug ministers of God" whose misdeeds in 1692 "put an official end to the theocracy." Schneider, Herbert Wallace, The Puritan Mind, Henry Holt & Co, 1930, p. 92.

- ↑ http://www.americanantiquarian.org/proceedings/44517578.pdf

- ↑ See link above containing obituary by CK Shipley in AAS Proceedings.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel E Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1936 p 494-497

- ↑ Detweiler, Robert (1975). "Shifting Perespectives on the Salem Witches". The History Teacher. 8: 598.

- ↑ David Levin, "Did the Mather's Disagree About the Salem Witchcraft Trials" (AAS, 1985) p.35. Levin's answer to the question presented in his title would seem to be no, the Mathers did not fundamentally disagree.

- ↑ Hansen 1969, p. 168.

- ↑ Hansen 1969, pp. 23-24.

- ↑ Hansen 1969, p. 189.

- ↑ Chadwick Hansen introduction to Robert Calef "More Wonders" (York Mail-Print, 1972) pp. v, xv note 4.

- ↑ David D Hall, "Witchcraft and the Limits of Interpretation" NEQ Vol 58 No. 2 (June, 1985) see p 261-3. https://www.jstor.org/stable/365516 Note, Hall doesn't mention the September 2, 1692 letter in this essay and no subsequent mention of the letter in his later publications has been located.

- ↑ Ken Silverman Selected Letters of Cotton Mather, (Louisiana, 1971) p 31.

- ↑ See link to this letter for a complex discussion of the provenance, as it did not arrive at the archives until 1985.

- ↑ Demos, John (2004). Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503131-8.

- ↑ Gregg, Larry (1992). The Salem Witch Crisis. New York: Praeger.

- ↑ Hopkins, Donald R. (2002). The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History; ISBN 0-226-35168-8, p. 140.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (2000), Part 6, Medicine, Science and Civilization in China, 6. Biology and Biological Technology, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 154 .

- ↑ Blake 1952, pp. 489–90

- ↑ Coss, Stephen. (2016). The Fever of 1721: the Epidemic that Revolutionized Medicine and American Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 87; ISBN 9781476783086

- ↑ Aronson and Newman 2002

- ↑ Gronim 2007, p. 248.

- ↑ Blake 1952, p. 489

- ↑ Niven, Steven J. (2013). "Onesimus (fl. 1706–1717), slave and medical pioneer, was born in the..." Hutchins center. Harvard College. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ↑ Blake 1952, pp. 490–91

- ↑ Winslow 1974, pp. 24–29

- ↑ Blake 1952, p. 495

- ↑ Blake 1952, p. 496

- ↑ Best, M (2007). "Making the right decision: Benjamin Franklin's son dies of smallpox in 1736". Qual Saf Health Care. 16 (6): 478–80. doi:10.1136/qshc.2007.023465. PMC 2653186. PMID 18055894.

- ↑ Mather 1911–1912, pp. 11, 628.

- ↑ Blake 1952, p. 493.

- ↑ The Smallpox Inoculation Hospital at St. Pancras, UK: BL, 2003-11-30, archived from the original on 2013-10-29, retrieved 2013-07-15

- ↑ Williams 1721.

- ↑ Blake 1952, p. 495.

- ↑ Niederhuber, Matthew (December 31, 2014). "The Fight Over Inoculation During the 1721 Boston Smallpox Epidemic". Harvard University.

- ↑ Williams 1721, p. 13.

- ↑ Douglass 1722, p. 11.

- ↑ Van de Wetering 1985, p. 46.

- ↑ Stout, The New England Soul, p. 102

- ↑ Heimert, Alan, Religion and the American Mind, p. 5 .

- ↑ Williams 1721, p. 4.

- ↑ Williams 1721, p. 2

- ↑ Williams 1721, p. 14

- ↑ Gronim 2007, p. 248.

- ↑ Mather 1721, p. 25, n. 15.

- ↑ Mather 1721, p. 2.

- ↑ Cooper, William (1721), A Letter from a Friend in the Country, Attempting a Solution of the Scruples and Objections of a Conscientious or Religious Nature, Commonly Made Against the New Way of Receiving the Small Pox, Boston: S. Kneeland, pp. 6–7 Apparently Cooper, also a minister, wrote this in cooperation with Colman because nearly the same response to the objections to inoculation is published under Colman's name as the last chapter to Colman (1722), A Narrative of the Method and Success of Inoculating the Small Pox in New England

- ↑ Van de Wetering 1985, p. 66, n. 55.

- ↑ Coss 2016, p. 269, p. 277

- ↑ Flemming, Gregory N. (2014). At the Point of a Cutlass: The Pirate Capture, Bold Escape, and Lonely Exile of Philip Ashton. Lebanon NH: ForeEdge. ISBN 9781611685626. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Gosse, Philip (1924). The Pirates' Who's Who by Philip Gosse. New York: Burt Franklin. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ Edmonds, John Henry (1918). Captain Thomas Pound. Cambridge MA: J. Wilson and son. pp. 32–44. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ Mather, Cotton (1726). The vial poured out upon the sea. A remarkable relation of certain pirates brought unto a tragical and untimely end. Some conferences with them, after their condemnation. Their behaviour at their execution. And a sermon preached on that occasion. : [Two lines from Job]. Boston: Printed by T. Fleet, for N. Belknap. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Burdick 2009.

- ↑ Hovey 2009, p. 533.

- ↑ Smolinski 2009, pp. 280–81.

- ↑ Mather, Cotton (2008). True Crime: An American Anthology. Library of America. ISBN 978-1-59853-031-5. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ Meyers 2006, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Halttunen 1978, p. 311.

- ↑ "Thanksgiving's Wampanoag call: Come Over and Help Us!". Josiah Cotton. To every tribe. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

Sources

- Aronson, Stanley M; Newman, Lucile (2002), God Have Mercy on This House: Being a Brief Chronicle of Smallpox in Colonial New England, Brown University News Service .

- Bancroft, George (1874–1878), History of the United States of America, from the discovery of the American continent, Boston: Little, Brown, & co, ISBN 0-665-61404-7

- Bercovitch, Sacvan (1972), "Cotton Mather", in Emerson, Everett, Major Writers of Early American Literature, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press .

- Blake, John B (December 1952), "The Inoculation Controversy in Boston: 1721–1722", The New England Quarterly, 25 (4): 489–506, doi:10.2307/362582 .

- Boylston, Zabdiel. An Historical Account of the Small-pox Inoculated in New England. London: S. Chandler, 1726.

- Breslaw, Elaine G (2000), Witches of the Atlantic World: A Historical Reader & Primary Sourcebook, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-9850-0

- Burdick, Bruce (2009), Mathematical Works Printed in the Americas 1554–1700, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, ISBN 0-8018-8823-9

- Calef, Robert (1700), More Wonders of the Invisible World, London, ENG, UK: Nath Hillar on London Bridge .

- Calef, Robert (1823), More Wonders of the Invisible World, Salem: John D. and T.C. Cushing, Jr.

- Douglass, William (1722), The Abuses and Scandals of Some Late Pamphlets in Favor of Inoculation of the Small Pox, Boston: J. Franklin .

- Felker, Christopher D. Reinventing Cotton Mather in the American Renaissance: Magnalia Christi Americana in Hawthorne, Stowe, and Stoddard (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1993); ISBN 1-55553-187-3

- Gronim, Sara Stidstone (2006), "Imagining Inoculation: Smallpox, the Body, and Social Relations of Healing in the Eighteenth Century", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 80: 247–68, doi:10.1353/bhm.2006.0057 .

- Halttunen, Karen (1978), "Cotton Mather and the Meaning of Suffering in the Magnalia Christi Americana", Journal of American Studies, 12 (3): 311–29, doi:10.1017/s0021875800006460, JSTOR 27553427 .

- Hansen, Chadwick (1969), Witchcraft at Salem, New York: George Braziller, ISBN 0-451-61947-1 .

- Hovey, Kenneth Alan (2009), "Cotton Mather: 1663–1728", in Lauter, Paul, Heath Anthology of American Literature, A, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 531–33 .

- Kennedy, Rick (2015), The First American Evangelical: A Short Life of Cotton Mather, Eerdmans , xiv, 162 pp.

- Lovelace, Richard F (1979), The American Pietism of Cotton Mather: Origins of American Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MC; Washington, DC: American University Press; Christian College Consortium, ISBN 0-8028-1750-5 .

- Mather, Increase (1692) Cases of Conscience from University of Virginia Special Collections Library.

- Meyers, Karen (2006), Colonialism and the Revolutionary Period (Beginning–1800): American Literature in its Historical, Cultural, and Social Contexts, New York: DWJ .

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Mathers: Three Generations of Puritan Intellectuals, 1596–1728, ISBN 0-520-21930-9

- Monaghan, E. Jennifer (2005,7) Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America; ISBN 978-1-55849-581-4

- Montagu, Mary Wortley (1763), Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M—y W—y M—e, London: T. Becket and P.A. de Hondt .

- Silverman, Kenneth. The Life and Times of Cotton Mather; ISBN 1-56649-206-8

- Smolinski, Reiner (2006), "Authority and Interpretation: Cotton Mather's Response to the European Spinozists", in Williamson, Arthur; MacInnes, Allan, Shaping the Stuart World, 1603–1714: The Atlantic Connection, Leyden: Brill, pp. 175–203 .

- ——— (November 3, 2009) [2008], "How to Go to Heaven, or How to Heaven Goes? Natural Science and Interpretation in Cotton Mather's Biblia Americana (1693–1728)", The New England Quarterly, Farmville, VA: MIT Press Journals, Longwood University Library, 81 (2): 278–329, doi:10.1162/tneq.2008.81.2.278 .

- Upham, Charles Wentworth (1959), Salem Witchcraft, New York: Frederick Ungar, ISBN 0-548-15034-6 .

- ——— (1869), Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather, A Reply, Morrisania, Bronx: Project Gutenberg .

- Van De Wetering, Maxine (March 1985), "A Reconsideration of the Inoculation Controversy", The New England Quarterly, 58 (1): 46–67, doi:10.2307/365262 .

- Wendell, Barrett (1891), Cotton Mather, the Puritan priest, New York: Dodd, Mead & co .

- White, Andrew (2010), "Zabdiel Boylston and Innoculation", Today In Science History .

- Williams, John (1721), Several Arguments Proving that Inoculating the Smallpox is not Contained in the Law of Physick, Boston: J. Franklin .

- Winslow, Ola Elizabeth (1974), A Destroying Angel: The Conquest of Smallpox in Colonial Boston, Boston: Houghton Mifflin .

- Zirkle, Conway (1935), The beginnings of plant hybridization, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press .

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Cotton Mather |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cotton Mather. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cotton Mather |

- Works by Cotton Mather at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Cotton Mather at Internet Archive

- Works by Cotton Mather at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Cotton Mather's writings

- Mather's influential commentary, collegiateway.org

- The Wonders of the Invisible World (1693 edition) in PDF format

- The Threefold Paradise of Cotton Mather: An Edition of "Triparadisus" (PDF format)

- Cotton Mather's "~Resolved~", A Puritan Father's Lesson Plan, neprimer.com

- Cotton Mather's "The Story of Margaret Rule", bartleby.com