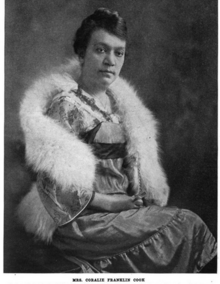

Coralie Franklin Cook

Coralie Franklin Cook (1861-1942) was an American educator and government official. She is also remembered as the first descendant of slaves from the Monticello estate to graduate from college.

Early life

Coralie Franklin was born enslaved at Lexington, Virginia, the daughter of Albert Franklin and Mary Elizabeth Edmondson Franklin. She was a descendant of Betty Hemings. Coralie Franklin's maternal great-grandfather, Brown Colbert, was a former slave owned by Thomas Jefferson; he settled in Liberia in 1833.[1] Coralie Franklin graduated from Storer College in 1880, the first known college graduate among the descendants of Jefferson's slaves at Monticello.[2] She studied elocution through courses in Boston and Philadelphia.[3]

Coralie's sister Mary Franklin was married to attorney J. R. Clifford, a civil rights leader associated with the Niagara Movement.[4]

Career

Before she married, Coralie Franklin taught a year of school in Hannibal, Missouri, and spent five years as head of the Home for Colored Orphans and Aged Women in Washington D. C.[3]

Coralie Franklin Cook taught elocution at Howard University[5] and at the Washington Conservatory of Music. She served on the Board of Education in Washington D. C., the second African-American woman after Mary Church Terrell to hold that appointment.[6] She was an early member of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs in 1896. She gave a presentation on "Negro Poets" at the First Race Amity Convention in 1921.[7]

Coralie Franklin Cook was active in the woman's suffrage movement.[8] She was the only African-American woman invited to give an official statement at Susan B. Anthony's 80th birthday celebration.[6] She was also a member of the Coleridge Taylor Choral Society,[9] and was elected president of the Washington Artists' Association.[10]

Personal life

In 1899, Coralie Franklin married George William Cook, a dean and professor at Howard University. They had a son, George William Cook Jr. The couple became adherents of the Bahá'í faith in about 1913.[7][11] She was widowed in 1931, and died in 1942, aged 80 years.

References

- ↑ "Brown Colbert" Getting Word: African American Families at Monticello at Monticello.org.

- ↑ "Coralie Franklin Cook" Getting Word: African American Families of Monticello at Monticello.org.

- 1 2 "Coralie Franklin Cook; Interesting Career of Colored Woman Who is to Lecture Here Soon" Democrat and Chronicle (November 28, 1902): 11. via Newspapers.com

- ↑ Coralie Franklin Cook House, Historic Harper's Ferry.

- ↑ Jacqueline M. Moore, Leading the Race: The Transformation of the Black Elite in the Nation's Capital, 1880-1920 (University of Virginia Press 1999): 125. ISBN 9780813919034

- 1 2 Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920 (Indiana University Press 1998): 63, 69-70. ISBN 9780253211767

- 1 2 Christopher Buck, Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy (Kalimat Press 2005): 78. ISBN 9781890688387

- ↑ "Mrs. Cook Makes Appeal for Woman's Rights" Washington Times (April 20, 1904): 12. via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Its Work Commended" Evening Star (April 29, 1903): 8. via Newspapers.com

- ↑ "Artists' Association Elects" Washington Post (November 11, 1917): 10. via Newspapers.com

- ↑ Coralie Franklin Cook, "Letter to 'Abdu'l-Bahá 'Abbás'" in Gwendolyn Etter Lewis and Richard Thomas, eds., Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá'ís in North America, 1898-2004 (Baha'i Publishing Trust 2006): 237. ISBN 9781931847261

External links

- Letter from Coralie Franklin Cook to W. E. B. DuBois (1918), from University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.