Copyfraud

Copyfraud refers to false copyright claims by individuals or institutions with respect to content that is in the public domain. Such claims are wrongful, at least under U.S. and Australian copyright law, because material that is not copyrighted is free for all to use, modify and reproduce. Copyfraud also includes overreaching claims by publishers, museums and others, as where a legitimate copyright owner knowingly, or with constructive knowledge, claims rights beyond what the law allows.

The term "copyfraud" was coined by Jason Mazzone, a Professor of Law at the University of Illinois.[2][3] Because copyfraud carries little or no oversight by authorities and few legal consequences, it exists on a massive scale, with millions of works in the public domain falsely labelled as copyrighted. Payments are therefore unnecessarily made by businesses and individuals for licensing fees. Mazzone states that copyfraud stifles valid reproduction of free material, discourages innovation and undermines free speech rights.[1]:1028[4] Other legal scholars have suggested public and private remedies, and a few cases have been brought involving copyfraud.

Definition

Mazzone describes copyfraud as:

- Claiming copyright ownership of public domain material.[1]:1038

- Imposition by a copyright owner of restrictions beyond what the law allows.[1]:1047

- Claiming copyright ownership on the basis of ownership of copies or archives.[1]:1052

- Attaching copyright notices to a public domain work converted to a different medium.[1]:1044–45

Analysis

Mazzone argues that copyfraud is usually successful because there are few and weak laws criminalizing false statements about copyrights, lax enforcement of such laws, few people who are competent to give legal advice on the copyright status of commandeered material, and few people willing to risk a lawsuit to resist the fraudulent licensing fees:

Copyright law itself creates strong incentives for copyfraud. The Copyright Act provides for no civil penalty for falsely claiming ownership of public domain materials. There is also no remedy under the Act for individuals who wrongly refrain from legal copying or who make payment for permission to copy something they are in fact entitled to use for free. While falsely claiming copyright is technically a criminal offense under the Act, prosecutions are extremely rare. These circumstances have produced fraud on an untold scale, with millions of works in the public domain deemed copyrighted, and countless dollars paid out every year in licensing fees to make copies that could be made for free. Copyfraud stifles valid forms of reproduction and undermines free speech.[1]

Mazzone continues: "[C]opyfraud upsets the constitutional balance and undermines First Amendment values", chilling free expression and stifling creativity.[1]:1029–30

In the U.S. Copyright Act, only two sections deal with improper assertions of copyright on public domain materials: Section 506(c) criminalizes fraudulent uses of copyright notices, and Section 506(e) punishes knowingly making a false representation of a material fact in the application for copyright registration.[1]:1036 Section 512(f) additionally punishes using the safe harbor provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act to remove material the issuer knows is not infringing. But the U.S. Copyright Act does not expressly provide for any civil actions to remedy claims of copyright on public domain materials, nor does the Act prescribe relief for individuals who refrain from copying or pay for copying permission to an entity that engages in copyfraud.[1]:1030 Professor Peter Suber argued in a 2011 article that the United States should "make the penalties for copyfraud (false claim of copyright) at least as severe as the penalties for infringement; that is, take the wrongful decrease in the circulation of ideas at least as seriously as the wrongful increase in the circulation of ideas."[5]

Section 202 of the Australian Copyright Act 1968, which imposes penalties for "groundless threats of legal proceedings", provides a cause of action in that country for any false claims of copyright infringement. This includes false claims of copyright ownership of public domain material, or claims to impose copyright restrictions beyond those permitted by the law.

American legal scholar Paul J. Heald, in a 1993 paper published in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law, explored the possibility that payment demands for spurious copyrights might be resisted in civil lawsuits under a number of commerce-law theories: (1) Breach of warranty of title; (2) unjust enrichment; (3) fraud; and (4) false advertising.[7] Heald cited a case in which the first of these theories was used successfully in a copyright context: Tams-Witmark Music Library v. New Opera Company.[8] In this case

[A]n opera company purchased the right to perform the opera The Merry Widow for $50,000 a year. After a little more than a year of performances, the company discovered that the work had passed into the public domain several years before due to a failure on the part of the copyright holder to renew the copyright. It ceased paying royalties, and after being sued by the owner of the abandoned copyright, counterclaimed for damages in the amount paid to the owner on a breach of warranty/failure of consideration theory. The trial court awarded the opera company $50,500 in damages, and the court of appeals affirmed the judgement, finding that The Merry Widow "passed, finally, completely and forever into the public domain and became freely available to the unrestricted use of anyone. ... New Opera's pleas of breach of warranty and total failure of consideration were established, and by undisputed proof."

Cory Doctorow, in a 2014 Boing Boing article, noted the "widespread practice of putting restrictions on scanned copies of public domain books online" and the many "powerful entities who lobby online services for a shoot now/ask questions later approach to copyright takedowns, while the victims of the fraud have no powerful voice advocating for them."[9] Professor Tanya Asim Cooper wrote that Corbis's claims to copyright in its digital reproductions of public domain art images are "spurious ... abuses ... restricting access to art that belongs to the public by requiring payment of unnecessary fees and stifling the proliferation of new, creative expression, of 'Progress' that the Constitution guarantees.[10] Charles Eicher pointed out the prevalence of copyfraud with respect to Google Books, Creative Commons' efforts to "license" public domain works, and other areas. He explained one of the copyfraudsters' unscrupulous methods: After you scan a public domain book, "reformat it as a PDF, mark it with a copyright date, register it as a new book with an ISBN, then submit it to Amazon.com for sale [or] as an ebook on Kindle. Once the book is listed for sale ... submit it to Google Books for inclusion in its index. Google earns a small kickback on every sale referred to Amazon or other booksellers."[11] Eicher suggests several remedies:

Government should act [by using its regulatory power] to secure its authority over copyrights. ... Private interests should be prohibited from exerting pseudo-regulatory powers. ... Anti-trust actions could break up the newly forming publishing cartel [of Google and Amazon] before it becomes entrenched. ... Google's orphan books settlement should be given further judicial review and invalidated. ... Google and Amazon should be prohibited from offering books with false copyrights, the public should be empowered to flag copyfraud books and issue a take-down notice.[11]

Notable cases and examples

- In 1984, Universal Studios sued Nintendo to stop Nintendo from profiting on its Donkey Kong arcade game, claiming that Donkey Kong was too similar to Universal's King Kong. Nintendo's lawyers showed that Universal had successfully argued, in 1975 legal proceedings against RKO General, that King Kong was in the public domain. Nintendo also won the appeal, a counterclaim, and a further appeal.[13][14][15]

- In 2006, Michael Crook filed false Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) claims against websites, claiming copyright on screenshots of his appearance on the Fox News Channel show Hannity & Colmes. In a March 2007 settlement, Crook agreed to withdraw the claims, "take a copyright law course and apologize for interfering with the free speech rights of his targets".[16][17]

- In 2013, the Arthur Conan Doyle estate was accused of copyfraud by Leslie Klinger in a lawsuit in Illinois for demanding that Klinger pay a license fee for the use in his book of the character Sherlock Holmes and other characters and elements in Conan Doyle's works published before 1923. The US Supreme Court agreed with Klinger, ruling that these characters and elements are in the American public domain.[18][19]

- In 2013, Good Morning to You Productions, a documentary film company, sued Warner/Chappell Music for falsely claiming copyright to the song "Happy Birthday to You".[20][21] In September 2015, the court granted summary judgement ruling that Warner/Chappell's copyright claim was invalid, and that the song is in the public domain, except for Warner/Chappell's specific piano arrangements of the song.[22][23]

- In 2015, the American Antiquarian Society, previously criticized for claiming propriety rights over its collections material in the public domain, updated its website to reflect a rights and reproductions policy that makes no claims to copyright. The AAS allows users to "freely download and use any of [the] images" on its online image database, and it does not require a user to cite the library as a source. Additionally, the AAS now allows unrestricted photography within its reading room.[1]:1053 [24]

- In 2015, two people obtained a 3D scan of the famous Bust of Nefertiti displayed at the Neues Museum in Berlin. They released the data on the internet, allowing the public to copy the bust. Their aim was to defy "a culture of 'hyperownership'" and "the strict limitations that museums often place on sharing the informational data regarding their collection with the public. ... Even when their cases lack legal support, museums and governments can try to use copyright or contract law to restrict access to cultural materials, to claim that they own all of the data and images outright, or to use digital rights management technology to lock up their data altogether. The result is 'copyfraud'".[3]

- In 2015, Lenz v. Universal Music Corp. affirmed a holding that copyright owners must consider fair use in good faith before issuing a takedown notice for content posted on the internet.[25][26] Boing Boing considers such uses of the DMCA to be "bogus complaints" a kind of copyfraud.[27] Improper claims of copyright with respect to works used under a free license, such as one by German royalty collector GEMA in 2011, have been termed copyfraud.[28]

- In 2015 Ashley Madison issued numerous DMCA notices to try to stop journalists and others from using public domain information. Sony did the same in 2014.[29]

- In 2016, photographer Carol M. Highsmith sued two stock photography organizations, Getty Images and Alamy, for $1.35 billion over their attempts to assert copyright over, and charge fees for the use of, 18,755 of her images, which she releases royalty-free. Getty had sent her a bill for one of the images, which she used on her own website.[30][31] In November 2016, the court dismissed the lawsuit with respect to the federal copyright claims, and the remaining issues were settled out of court.[32]

- In 2016, lawsuits were filed by the same legal team who brought the 2013 "Happy Birthday" lawsuit, alleging false claims of copyright with respect to the songs "We Shall Overcome" and "This Land Is Your Land".[33]

- In 2017, Portugal passed amendments to its anti-circumvention laws making it illegal to impose digital rights management to restrict usage of works that were already in the public domain.[34]

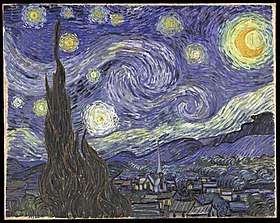

- In November 2017, 27 prominent art historians, museum curators and critics (including Bendor Grosvenor, Waldemar Januszczak, Martin Kemp, Janina Ramirez, Robin Simon, David Solkin, Hugh Belsey, Sir Nicholas Goodison, and Malcolm Rogers) wrote to The Times newspaper to urge that "fees charged by the UK's national museums to reproduce images of historic paintings, prints and drawings are unjustified, and should be abolished". They commented that "[m]useums claim they create a new copyright when making a faithful reproduction of a 2D artwork by photography or scanning, but it is doubtful that the law supports this". They argued that the fees inhibit the dissemination of knowledge, the very purpose of public museums and galleries, and so "pose a serious threat to art history". Therefore, they advised the UK's national museums "to follow the example of a growing number of international museums (such as the Netherlands' Rijksmuseum) and provide open access to images of publicly owned, out-of-copyright paintings, prints and drawings so that they are free for the public to reproduce".[35]

- Online Policy Group v. Diebold, Inc. (a misrepresentation case related to a DMCA takedown)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Mazzone, Jason (2006). "Copyfraud" (PDF). New York University Law Review. 81 (3): 1026. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Jason Mazzone, Professor, Lynn H. Murray Faculty Scholar in Law" Archived 2015-12-28 at the Wayback Machine., University of Illinois College of Law, accessed June 17, 2015

- 1 2 Katyal, Sonia K. and Simone C. Ross. "Can technoheritage be owned?" Archived 2016-06-06 at the Wayback Machine., The Boston Globe, May 1, 2016

- ↑ Mazzone, Jason. "Too Quick to Copyright", Legal Times, volume 26, no. 46

- ↑ Suber, Peter. "Open Access and Copyright", SPARC Open Access Newsletter, July 2, 2011, accessed July 17, 2016

- ↑ "Comparison: two modern editions of a public domain work" Archived 2015-07-07 at the Wayback Machine., Public Domain Sherpa

- ↑ Heald, Paul J. "Payment Demands for Spurious Copyrights: Four Causes of Action" Archived 2016-05-28 at the Wayback Machine., Journal of Intellectual Property Law, vol. 1, 1993–1994, p. 259

- ↑ Tams-Witmark Music Library v. New Opera Company, 81 N.E. 2d 70 (NY 1948)

- ↑ Doctorow, Cory. "Copyfraud, uncertainty and doubt: the vanishing online public domain" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine., Boing Boing, June 25, 2014, accessed June 16, 2015

- ↑ Cooper, Tanya Asim. "Corbis & Copyright?: Is Bill Gates Trying to Corner the Market on Public Domain Art?" Archived 2015-10-30 at the Wayback Machine., Intellectual Property Law Bulletin, vol. 16, p. 1, University of Alabama 2011

- 1 2 Eicher, Charles. "Copyfraud: Poisoning the public domain" Archived 2016-02-04 at the Wayback Machine., The Register, June 26, 2009, accessed June 16, 2015

- ↑ Photo at the White House Archived 2015-09-22 at the Wayback Machine., The White House flickr account, posted December 6, 2009. The Electronic Frontier Foundation noted that "official photos by the official White House photographer ... aren't copyrightable [and] should instead be flagged as public domain." See D'Andrade, Hugh. "White House Photos – Does the Public Need a License to Use?" Archived 2015-07-12 at the Wayback Machine., Electronic Frontier Foundation, May 1, 2009, accessed July 11, 2015. Techdirt wrote of another White House photo, "the White House is ignoring what that license says in claiming that the photograph 'may not be manipulated in any way.' That's clearly untrue under the law and a form of copyfraud, in that they are overclaiming rights." Masnick, Mike. "President Obama Is Not Impressed With Your Right to Modify His Photos" Archived 2015-07-13 at the Wayback Machine., Techdirt, November 20, 2012, accessed July 11, 2015

- ↑ United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit (October 4, 1984). Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

- ↑ United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit (July 15, 1986). Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

- ↑ Reyners, Conrad (March 17, 2008). "The plight of Pirates on the information superwaves". Salient. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ↑ "Diehl v. Crook | Electronic Frontier Foundation". Eff.org. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ Cobia, Jeffrey. "The DMCA Takedown Notice Procedure: Misues, Abuses, and Shortcomings of the Process", Minn. J. L. SCI. & Tech. 2009;10(1):387-411

- ↑ Davies, Nick. "Sherlock Holmes will stay in public domain". Melville House. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Conan Doyle Estate: Denying Sherlock Holmes Copyright Gives Him 'Multiple Personalities'". Hollywoodreporter.com. 2013-09-13. Archived from the original on 2013-09-16. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- ↑ Masnick, Mike. "Lawsuit Filed to Prove Happy Birthday Is in The Public Domain; Demands Warner Pay Back Millions of License Fees" Archived 2013-10-14 at the Wayback Machine., Techdirt.com, June 13, 2013

- ↑ Masnick, Mike. "Warner Music Reprising the Role of the Evil Slayer of the Public Domain, Fights Back Against Happy Birthday Lawsuit" Archived 2013-11-03 at the Wayback Machine., Techdirt.com, September 3, 2013; and Johnson, Ted. "Court Keeps Candles Lit on Dispute Over 'Happy Birthday' Copyright" Archived 2017-06-28 at the Wayback Machine., Variety, October 7, 2013

- ↑ Mai-Duc, Christine (September 22, 2015). "'Happy Birthday' Song Copyright Is Not Valid, Judge Rules". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ↑ Gardner, Eriq (September 22, 2015). "'Happy Birthday' Copyright Ruled to Be Invalid". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Rights and Reproductions at the American Antiquarian Society". Americanantiquarian.org. 2009-04-16. Archived from the original on 2009-06-27. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ Lenz v. Universal Music Corp., 801 F.3d 1126 (2015), (9th Cir. 2015)

- ↑ Lenz v. Universal Music Corp Archived 2016-11-25 at the Wayback Machine., 572 F. Supp. 2d 1150 (N.D. Cal. 2008).

- ↑ Doctorow, Cory. "Copyfraud: Disney's bogus complaint over toy photo gets a fan kicked off Facebook" Archived 2016-05-07 at the Wayback Machine., Boing Boing, December 11, 2015

- ↑ "GEMA Strikes Again: Demands Licensing Fees For Music It Has No Rights To" Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine., Techdirt.com, October 10, 2011, accessed May 16, 2016; "Musikpiraten e.V. examines option to sue GEMA for copyfraud" Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine., Musikpiraten e.V., September 30, 2011, accessed May 16, 2016; and Van der Sar, Ernesto. "Music Royalty Collectors Accused of Copyfraud" Archived 2016-06-24 at the Wayback Machine., Torrent Freak, October 2, 2011, accessed May 14, 2016

- ↑ Doctorow, Cory. "Ashley Madison commits copyfraud in desperate bid to suppress news of its titanic leak" Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine., Boing Boing, August 20, 2015

- ↑ Dunne, Carey (July 27, 2016). "Photographer Files $1 Billion Suit Against Getty for Licensing Her Public Domain Images". Hyper Allergic. Archived from the original on July 28, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Masnick, Mike. "Photographer Sues Getty Images For $1 Billion For Claiming Copyright On Photos She Donated To The Public". Techdirt. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016. includes a copy of the lawsuit

- ↑ Walker, David. "Court Dismisses $1 Billion Copyright Claim Against Getty" Archived 2017-09-01 at the Wayback Machine., PDNPulse, November 22, 2016

- ↑ Gardner, Eriq. "Happy Birthday' Legal Team Turns Attention to 'We Shall Overcome'" Archived 2016-04-16 at the Wayback Machine., Billboard, April 12, 2016; and Farivar, Cyrus. "Lawyers who yanked 'Happy Birthday' into public domain now sue over 'This Land'" Archived 2017-08-13 at the Wayback Machine., Ars Technica, June 18, 2016

- ↑ "Portugal Bans Use of DRM to Limit Access to Public Domain Works". Electronic Frontier Foundation. 2017-10-23. Archived from the original on 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- ↑ Grosvenor, Bendor; et al. (November 6, 2017). "Museums' fees for image reproduction". The Times. p. 34.

Further reading

- Mazzone, Jason (2011). Copyfraud and Other Abuses of Intellectual Property Law. Stanford Law Books. ISBN 0804760063.

- Ebbinghouse, Carol (January 2008). "Copyfraud' and Public Domain Works". Searcher: The Magazine for Database Professionals. 16 (1): 40–62.

- Gévaudan, Camille (3 December 2015). "Quand Wikimédia défend le domaine public contre le «copyfraud»" [How Wikimedia defends the public domain against "Copyfraud"]. Liberation (in French).

- Blanc, Sabine (1 April 2016). "Le copyfraud, entre circulation des savoirs et contraintes". La Gazette (in French).

- Gary, Nicolas (23 January 2016). "Open Access, Panorama, Copyfraud : République numérique, la loi se dessine". ActuaLitté (in French).

- Cronin, Charles Patrick Desmond (8 March 2016). "Possession is 99% of the Law: 3D Printing, Public Domain Cultural Artifacts & Copyright". USC Law Legal Studies Paper No. 16-13. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2731935.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Copyfraud. |