Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls

| Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home | |

|---|---|

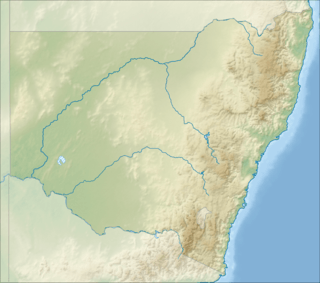

Location of Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home in New South Wales | |

| Location | 39 Rinkin Street, Cootamundra, Cootamundra-Gundagai Regional Council, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 34°38′26″S 148°02′45″E / 34.6406°S 148.0457°ECoordinates: 34°38′26″S 148°02′45″E / 34.6406°S 148.0457°E |

| Built | 1912–1974 |

| Architect | Morell and Kemp |

| Owner | Young Local Aboriginal Land Council |

| Official name: Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home; Cootamundra Girls' Home; Aboriginal Girls' Training Home; Bimbadeen Bible College; | |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Designated | 17 February 2012 |

| Reference no. | 1873 |

| Type | Place of significance |

| Category | Aboriginal |

The Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls, commonly known as "Bimbadeen", located at Cootamundra, New South Wales operated by the New South Wales Aborigines Welfare Board from 1911 to 1968 to provide training to girls forcibly taken from their families under the Aborigines Protection Act (1909). These girls were members of the Stolen generations[1] and were not allowed any contact with their families, being trained to work as domestic servants.[2][3]

Reports of girls being abused were related in Bringing Them Home, the report into the Stolen Generations.[4]

The building that housed the Home was later taken over by the Aboriginal Evangelical Fellowship as a Christian vocational, cultural and agricultural training centre called Bimbadeen College.[2] It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 17 February 2012.[5]

History

Background

Historically Aboriginal children were separated from their families from the earliest days of the colony. Governor Macquarie established the first Native Institution in Parramatta as early as 1814 and in 1823 another Native Institution was started in Blacktown. Both these institutions were considered failures, one reason being that once parents realised their children wouldn't be allowed to come home and wouldn't give them up to the institutions. The Government of New South Wales also subsidised missionary activity among the Aboriginal people, including that of the London Missionary Society in the 1820s and 1830s. On the frontier of Wellington Valley the Reverend Watson gained a reputation for stealing Aboriginal children and as a consequence the Wiradjuri hid their children from the white men.[5]

With the spread of settlers and their livestock came conflict and dispossession. The first bill for the Protection of Aborigines was drafted in 1838 after the Myall Creek massacre in June that year. Thus began a systemic government approach to the regulation and control of the lives of Aboriginal people that got tighter and tighter until the 1967 referendum finally brought significant change.[5]

Until 1881 Aboriginal people were under the jurisdiction of the Colonial Secretary, Police and the Lands Department. In 1880 a private body known as the Association for the Protection of Aborigines was formed and following agitation by this body, the Government appointed a Protector of Aborigines, Mr. George Thornton MLC. The Board for the Protection of Aborigines was subsequently created in 1883. "The objectives of the Board were to provide asylum for the aged and sick, who are dependent on others for help and support; but also, and of at least equal importance to train and teach the young, to fit them to take their places amongst the rest of the community" (State Records). This objective became the basis of future child removal policy: that the inferiority of the Aborigines would only be dealt with by removing the children and educating them in white ways.[5]

In Darlington Point Reverend Gribble established Warangesda Mission in 1880 and one of his concerns was what he perceived to be the vulnerability of young Aboriginal women in an environment that was dominated by immoral white men. A separate girls' dormitory was set up at Warangesda in 1883 and was first supervised by Mrs. Gribble as a home to mothers with their young children, single women, and girls. Although there was a school at Warangesda, the dormitory followed the institutional model of its time, and taught housekeeping skills to the girls to prepare them for respectable employment in menial duties on nearby stations. It also housed them separately in a building which included a dining room and kitchen as well as the dormitory room. Girls were brought in from many places and kept under supervision of dormitory matrons as well as Mrs. Gribble or the wives of later managers.[6]

When Warangesda Mission became an Aboriginal Station in 1884 the Aboriginal Protection Board continued to send Aboriginal girls to the Warangesda girls' dormitory. It was the Warangesda Mission/Station girls' dormitory which became the model or prototype for the girls' home established at Cootamundra. When Warengesda closed the policy had been for a number of years to send the girls from the dormitory to the Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home.[5]

Frustrated by the lack of legislative power to control the education and lives of Aboriginal children the Aborigines Protection Board successfully lobbied for a new act which was introduced in 1909. The Board's Annual Reports of 1909 and 1911 show the emphasis on training of Aboriginal children. The Board felt limited by the Act because it only gave them direct control over children over 14 who could be apprenticed. To remove younger children they had to apply to the magistrate under the Neglected Children and Juvenile Offenders Act 1905. The Board was of the opinion that the children would only become good and proper members of "industrial society" if they were completely removed and not allowed to return.[7] The underlying assumption by white society, as ever, was that Aboriginal people lacked the intellect to undertake anything but menial tasks. This later translated into the limits on the types of training provided; girls training for domestic service and the boys for labouring.[5]

The Aborigines Protection Act was amended in 1915 and again in 1918 giving the Board the right "to assume full control and custody of the child of any aborigine, if after due inquiry it is satisfied that such a course is in the interest of the moral or physical welfare of such child. The Board may remove such child to such control and care as it thinks best." (Aborigines Protection Amending Act, 1915, 4. 13A.) A court hearing was no longer necessary. If the parents wanted to appeal it was up to them to go to the court.[5]

The depression and drought years of the 1920s and 1930s were particularly difficult for Aboriginal people. Conditions in the reserves remaining from the soldier settlement land redistribution, were poor, often overcrowded, and it was easy for the government to prove neglect and remove Aboriginal children. In 1937, in response to public pressure from academic and missionary groups sympathetic to Aboriginal people, a meeting was convened of State and Commonwealth Aboriginal authorities. The result was an official assimilation policy formed on the premise that "full-blood" Aborigines would be soon extinct and the "half-caste" should be absorbed into society. Meanwhile, the Aboriginal people were organising to become a force of resistance. The Sesquicentenary was marked by a National Day of Mourning and a call for the Abolition of the Protection Board.[8][5]

The Aborigines Protection Board was finally abolished and replaced by the Aborigines Welfare Board in 1940. Aboriginal children were then subject to the Child Welfare Act 1939 which required a magistrate's hearing and the child had to be proven neglected or uncontrollable. Aboriginal children continued to be sent to Cootamundra, Bomaderry and Kinchela, some went to Mittagong or Boystown. There were no specific homes for uncontrollable Aboriginal children so these were sent to State corrective institutions such as Mt Penang or Parramatta Girls.[9] The education of Aboriginal children had generally been one of segregation until, in 1940, the Department of Education officially took on the role.[5]

In the 1960s the work of British psychiatrist John Bowlby on "attachment theory", began to influence the institutional care of children in Australia. That an infant needs to develop a relationship with at least one primary caregiver for social and emotional development to occur normally: rather than only being treated with affection as a reward (Cupboard Love) which was the prevailing theory of the 1940s. Fostering then became the preferred option and a more common occurrence. In accordance with the assimilation policy which was still prevalent, Aboriginal children were fostered with non-Aboriginal parents.[5]

In May 1967 a referendum changed the Australian constitution bringing positive changes for the Aboriginal people. One resultant change was the abolition of the Aborigines Welfare Board in 1969. After this time non-Aboriginal girls were admitted to Cootamundra Girls Home.[5]

History of Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home

The former Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home is located on lands described by Tindale as those of the Wiradjuri language group. (Tindale) Aboriginal people from the area identify themselves as being part of the Wiradjuri nation. Wiradjuri means "people of the three rivers", these rivers being the Macquarie, Lachlan and Murrumbidgee. Clashes between the new European settlers and the local Aboriginal people were common around the Murrumbidgee and even further north, particularly between 1839 and 1841. These violent incidents have been termed the "Wiradjuri wars". (Read)[5]

Charles Sturt and George Macleay visited the area in 1829 and by 1837 John Hurley & Patrick Fennell were licensed to pasture stock on Coramundra Run, which grew to encompass 50,000 acres. By 1861 the town of Cootamundra was gazetted and the first lots were sold a year later coinciding with commencement of gold mining east of the town at Muttama gold fields. The opening of the railway in 1877 led to the expansion of the settlement.[5]

In 1889 the first Cootamundra Hospital was opened on a hill east of the town on a site of 35 acres after 5 years of fund raising. The hospital was designed by government architects, Morell and Kemp of Sydney. The original plan had the main brick building with verandas on four sides and a separate kitchen to the north. The large ward was in the centre of the building and later became the older girls' dormitory. The entry was from a circular drive in front of the southern verandah which faced the town below. In 1910 the Cootamundra District Hospital moved to a new more central site in town and the old hospital on the hill closed.[5]

In the meantime, the Aborigines Protection Board had been looking for accommodation for Aboriginal girls under 14 who were too young to enter domestic service. The hospital buildings being set apart but close to a town and railway were considered suitable and in 1911 were purchased to become the Cootamundra Home for Orphan and Neglected Aboriginal Children. There is oral history reference to another building referred to as the nurses quarters, the fever hut and the old school.[10] Its exact location isn't known at this stage. The original morgue, originally located near the well was moved in the 1950s to the other end of the kitchen and has since been demolished. The well was twelve metres deep and four metres across with a domed concrete lid, it was filled in during the 1980s. Water supplies were often unreliable until the town water was connected in the 1940s. The operating theatre became matron's room; the committee room, her sitting room; the dispensary her office. The verandah were enclosed for extra dormitory space on the southern and eastern sides. In the 1920s and 1930s the kitchen was extended and a new caretaker's cottage was built. A weather shed was built near the school, a pan-system toilet block, laundry and a dairy. There was also a windmill to pump water from a dam below the main building to the vegetable garden and orchard. In the paddocks Lucerne was grown to support six cows and there was a chicken run. The home must have been reasonably self-sufficient however in the reports of the Board there is reference to the high cost of maintenance of Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home as compared to Kinchela Aboriginal Boys' Training Home.[11] The Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home had its own school up until 1946 (Cootamundra East Aboriginal School). After 1946 the girls attended the Cootamundra Public School.[5]

The climate at Cootamundra has an extreme range of temperatures which made conditions at the Home relatively harsh, particularly for those girls from more temperate or sub-tropical areas. The routine at the home has since been described by the former residents as very strict and the days were long.[12][13] The Home was planned according to early twentieth century social welfare policy which housed the children in dormitories according to age. The older girls were considered to be a corruptible influence on the younger ones and were therefore separated. The girls were looked after by staff who lived on the premises including a matron.[5]

The removal of Aboriginal children from their families, culture and "Country" created a dislocation for the girls as was described by one submission to the Commission of Inquiry. "Cootamundra was so different from the North Coast, it was cold and dry. I missed the tall timbers and all the time I was away there was this loneliness inside of me."[14][5]

Girls were sent to Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home until the age of 14 and then they were sent out to work. Many girls became pregnant whilst in domestic service, only to have their children in turn removed and institutionalised back at Cootamundra or Bomaderry. Generations of Aboriginal women passed through Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home until its closure.[15] Some girls were sent to Parramatta Girls' Industrial School which was a correctional facility for all girls regardless of ethnicity.[5]

In the 1950s the approach to child welfare institutions was to change when new theories were introduced and the concept of mother child bonds were considered more important. The numbers of girls at Cootamundra dropped significantly after this time when foster caring became a more regular occurrence, although the practice of assimilation continued with the girls being placed in "white" families.[5]

In 1969 the NSW Aborigines Welfare Board was abolished, Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home was passed over to the care of the NSW Department of Youth and Community Services and eventually closed its doors in 1974. Non- Aboriginal children were also sent to the Home after 1969. From the mid-1970s the NSW Department of Youth and Community Services began employing Aboriginal workers in the placement of Aboriginal children.[5]

The 35 acre property that is the former Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home has since passed on to the Young Local Aboriginal Land Council who, in turn, has leased the property, on a long term lease, to the Aboriginal Evangelical Fellowship as a Christian vocational, cultural and agricultural training centre called Bimbadeen College.[5]

Description

The former Cootamundra Hospital and the former Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home were built upon a hill north east of Cootamundra. The property consists of a large parcel of land which had room for buildings as well as orchards and livestock such as dairy cows.[5]

The earliest building on the site is a face brick early Federation style building built in 1887 as the first Cootamundra hospital. The layout of the hospital includes a large central room under a hip roof which was the ward and later became a dormitory utilising the same hospital beds. The ward faces south west and has highlight windows above the front verandah roof. The front of the building faced south west towards the town of Cootamundra. A circular carriageway was on what is now lawn in front of the verandah. The verandah was extended along its length and enclosed during the time of the Girls' Home and used as a second dormitory. The enclosed extension has since been demolished due to termite damage. In the south eastern corners of the central ward/dormitory are two square rooms with pyramidal roofs originally used as a bathroom and latrines with another verandah in between. This verandah was also enclosed by the Girls' Home and used as a box room. An additional room was added to this in the 1940s for use as an infants' dormitory. At the north western end of the main dormitory is a transverse brick wing with a hip roof joined to the main ward by a hall and used as a Matron's room and locker room. This building is intersected by another hip roof building originally housing the operating theatre and then the Matron's bedroom. The north east side of the building also had a verandah which was extended and enclosed for use as a dining room by the Girls' Home. Beyond this was a separate brick kitchen. In between the kitchen and the main building were an assembly area and a well. Adjacent to the kitchen was an old morgue which had been moved several times on the site and was used by the Girls' Home as a store room and also a punishment room; it has since been demolished however the foundation slab remains. The buildings are surrounded by extensive lawns and some large trees, such as Pepper Trees and Eucalypts. The tennis court is still in situ although not maintained. There is an original dairy to the south of the main building which is in poor condition. A caretaker's cottage was constructed between 1920 and 1940 at the front gate. There was a boiler which has had test excavation and can be regarded as a potential archaeological resource.[5]

After the closure of the Girls' Home the site was taken up by the Bimbadeen Evangelical College. Bimbadeen has added to and made alterations to the main Girls' Home complex. The area between the kitchen and the main building has been fully enclosed for use as an auditorium. A large dining room has been added to the north of the kitchen. A blockwork ablutions building has been constructed on the site of an earlier building. A large farm shed and six new residences have been added along the northern boundary away from the main complex. The circular carriageway used by the hospital is no longer evident and the main entrance is in the location of the old well.[5]

The original buildings as used by the Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home have been adapted but can still be clearly read amongst the additions.[5]

References

- ↑ Debra Jopson, (23 May 1997) Stolen lives, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, p. 38

- 1 2 Horton, David (ed.), (1994), The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia, Vol. 1, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, , p. 228.

- ↑ Tatjana Clancy, (13 August 2012, 5:06 p.m.), Cootamundra Remembers, Afternoons with Genevieve Jacobs, ABC Canberra 666

- ↑ Tony Stephens, (28 January 1998), Blood and Guts, Sydney Morning Herald', Sydney, p. 9

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 "Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Training Home, New South Wales State Heritage Register (NSW SHR) Number H01873". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ↑ Warangesda HOD 5055095

- ↑ (Brindley p48, A board official quoted by P Read and C Edwards.)

- ↑ The Abo Call 1st Sept 1938

- ↑ Brindley p60

- ↑ Brindley 83

- ↑ Brindley 93 & 94

- ↑ Aboriginal Women's Heritage, Wagga Wagga 34

- ↑ BTH 55

- ↑ BTH 54

- ↑ BTH Ch3

Bibliography

- Brindley, Merryl - Leigh, (1994). The Home on the Hill, The story behind Cootamundra Girl's Home,.

- Creative Spirits. "Timeline of the Stolen Generations".

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (1997). "Bringing Them Home - National Inquiry into Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families".

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Bringing Them Home Resource Sheets.

- Kabaila, Peter (1995). Wiradjuri Places Volume 1.

- Read, Peter (2007). The Stolen generations.

- Prepared by Carol Kendall assisted by Peter Read. Link-Up Booklet.

Attribution

![]()