Competitive karuta

Competitive karuta (競技かるた Kyōgi karuta) is an official Japanese card game that uses a deck of uta-garuta cards to play karuta, within the format and rules set by the All Japan Karuta Association.

Overview

Competitive karuta has been around since the start of the 19th century before the Meiji restoration, but the rules used vary in different regions. At the beginning of the 20th century the different rules were unified by a newly formed Tokyo Karuta Association, and the first competitive karuta tournament was held in 1904. The rules have been slightly modified since then.

The first attempt to establish a national association was done in 1934, and this later led to the foundation of the All Japan Karuta Association in 1957. The association has hosted tournaments for men since 1955, and women since 1957.

Today, competitive karuta is played by a wide range of people in Japan. Although the game itself is simple, playing at a competitive level requires a high-level of skills such as agility and memory. Therefore, it is recognized as a kind of sport in Japan.

Although karuta is very popular in Japan, there are very few competitive karuta players. It is estimated that there are currently 10,000 to 20,000 competitive karuta players in Japan, 2,000 of which are ranked as above C-class (or 1Dan) and registered in the “All Japan Karuta Association”.

There are several associations for karuta players including the “Nippon Karuta-in HonIn”, which emphasizes the cultural aspects of karuta.

The Japanese national championship tournament of competitive karuta is held every January at Omi Jingu (a Shinto Shrine) in Ōtsu, Shiga. The title Meijin has been awarded to the winner of the men's division since 1955, and the title Queen has been awarded to the winner of the women's division since 1957. Both winners are known as Grand Champions. A seven-time Grand Champion is known as an Eternal Master. The national championship for high school students is held every July.

Lately, the game has begun gaining international players as well. In September 2012 there was the first international tournament, and players from the U.S., China, South Korea, New Zealand, and Thailand participated.

Karuta cards

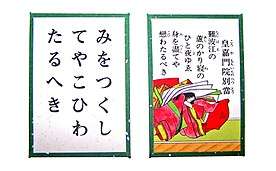

There are two decks in a karuta game. Each deck contains 100 cards, with a tanka poem printed on each. The two decks are:

- Yomifuda (lit. "Reading Card"); 100 cards, each with a picture of a poet with a complete tanka poem (5-7-5-7-7 syllables) by them.

- Torifuda (lit. "Grabbing Card"); 100 cards, each corresponding to a yomifuda but with only the last phrases of the poem (the ending 7-7 syllable lines).

Rules

Competitive karuta is a one-on-one game, facilitated by a reciter (card reader) and a judge. All official matches use cards made by Oishi Tengudo.

Each player randomly selects 25 of the 50 torifuda cards that are also randomly selected from a total of 100, and places them face-up in three rows in his or her territory. A player's territory is the space in front of the player, 87 cm wide and separated from their opponent's cards by 3 cm.[1] Players are then given 15 minutes to memorize all the cards in place, and for the final two minutes they are allowed to practice their strike at the cards.

The game starts by the reciter reading an introductory poem that is not part of the 100 poems. This introductory reading allows players to familiarize themselves with the reciter’s voice and the reading rhythm. Following the introductory poem, the reciter reads one of the 100 yomifuda. 50 of the yomifuda are in the game as torifuda, and the other 50 are karafuda (ghost cards) and do not correspond to torifuda in the game.

As soon as the players recognize which yomifuda is being read, they race to find and touch the corresponding torifuda. The first player to touch the torifuda "takes" the card and removes it from play. When a player takes a card from the opponent's territory, that player may transfer one of their own cards to their opponent. If both players touch the card at the same time, it is taken by the player whose territory it is in.

The first player to get rid of all the cards in their territory wins.

Otetsuki (Faults, False touches)

- Touching the wrong card in the same territory as the target card is not a penalty.[2] As a result, the players may toss away surrounding cards near the target card.

- Touching the wrong card in the wrong territory results in a penalty. The opponent may then transfer a card from their territory to the faulting player's.

- When a player touches any card when a ghost card is read, they incur a penalty.

Double faults

- If a player touches the wrong card in the opponent's territory and the opponent touches the correct card in the faulting player's territory, it is a double fault with a penalty of two cards.

- When a player touches any card in both territories when a ghost card is read, they incur a penalty of two cards.

The order of the cards in a player's territory may be rearranged at any time during the game. However, excessive rearrangement is considered poor sportsmanship.

Characteristics of the game

Good karuta players memorize all 100 tanka poems and the layout of the cards at the start of the match. The layout of the cards changes during the duration of the match.

There are 7 poems which have unique first syllables (Fu, Ho, Me, Mu, Sa, Se, Su), 42 with unique first 2 syllables, 37 poems with unique first 3 syllables, 6 poems with 4, 2 poems with 5 and, finally, 6 cards with unique first 6 syllables, so a player can discriminate between cards only when the second verse of the poem starts. There are 3 cards starting with Chi which are "Chihayafuru", "Chigirikina" and "Chigiriokishi", so a player must react as soon as he/she hears the beginning decisive part of the poem, which is called kimariji. As a result, fast thinking, reaction time, and physical speed is required. An average karuta game lasts about 90 minutes, including a 15-minute pre-match memorizing time. In national tournaments the winner usually plays 5 to 7 matches.

Mental and physical endurance are tested in the tournament. It is reported that tournament players may lose up to 2 kg (4.4 lb) during the process.[3]

Official Games

- Individual match

Individual tournaments are separated by the ranking group (Dan=grade). The ranking is as followed:

- A class; 4-Dan and above

- B class; 2 or 3-Dan

- C class; 1-Dan

- D class; intermediate

- E class; beginner

To participate in tournaments for higher classes, players must gain corresponding Dan by gaining sufficient results in lower classes that are set by the association, and the player must register as official member of the association if he or she wishes to enter any tournament higher than C class.

There are about 50 official tournaments every year which are counted toward the ranking of Dan.

Local tournaments may alter this ranking system or the form of the tournament by case. There are also tournaments ranked by their age or grade in school. Official tournaments are free to enter regardless of their age or gender, but some tournaments may limit this for certain ages, gender, and class of the players.

- Team Competition

The format of team competition is different from that of individual’s, and the format may differ from one tournament to another. For example, a common tournament will be done with teams of five to eight members, and teams will decide the order of their players for each game. Each class will compete for the total points and wins in the league.

Media coverage

Official tournaments are often covered by the media, and several drama, anime and manga plots revolve around competitive karuta.

- Manga

- Chihayafuru – by Yuki Suetsugu

- Karuta (manga) – by Kenjirō Takeshita

- Manten Irohakomachi – by Mariko Kosaka

- Anime

- Chihayafuru – by Yuki Suetsugu

- Chōyaku Hyakunin isshu: Uta Koi – by Kei Sugita

- Drama

- Karuta Queen – NHK General TV

- Live-action

- Chihayafuru – by Yuki Suetsugu

See also

- Ogura Hyakunin Isshu - the poetry anthology printed on the cards.

References

- ↑ Karutastone “How to play”

- ↑ Karutastone “Fouls (Otetsuki)”

- ↑ Waseda University “Don’t grab those karuta cards, let them fly!” accessed 2011-11-17