Collective action problem

A collective action problem is a situation in which all individuals would be better off cooperating but fail to do so because of conflicting interests between individuals that discourage joint action.[1][2] The collective action problem has been addressed in political philosophy for centuries, but was most clearly established in 1965 in Mancur Olson's The Logic of Collective Action. The collective action problem can be observed today in many areas of study, and is particularly relevant to economic concepts such as game theory and the free-rider problem that results from the provision of public goods. Additionally, the collective problem can be applied to numerous public policy concerns that countries across the world currently face.

Prominent theorists

Early thought

Although he never used the words "collective action problem," Thomas Hobbes was an early philosopher on the topic of human cooperation. Hobbes believed that people act purely out of self-interest, writing in Leviathan in 1651 that "if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies."[3] Hobbes believed that the state of nature consists of a perpetual war between people with conflicting interests, causing people to quarrel and seek personal power even in situations where cooperation would be mutually beneficial for both parties. Through his interpretation of humans in the state of nature as selfish and quick to engage in conflict, Hobbes's philosophy laid the foundation for what is now referred to as the collective action problem.

David Hume provided another early, more well-known interpretation of what is now called the collective action problem in his 1738 book A Treatise of Human Nature. Hume characterizes a collective action problem through his depiction of neighbors agreeing to drain a meadow:

Two neighbours may agree to drain a meadow, which they possess in common; because it is easy for them to know each others mind; and each must perceive, that the immediate consequence of his failing in his part, is, the abandoning the whole project. But it is very difficult, and indeed impossible, that a thousand persons should agree in any such action; it being difficult for them to concert so complicated a design, and still more difficult for them to execute it; while each seeks a pretext to free himself of the trouble and expence, and would lay the whole burden on others.[4]

In this passage, Hume establishes the basis for the collective action problem. In a situation in which a thousand people are expected to work together to achieve a common goal, individuals will be likely to free ride, as they assume that each of the other members of the team will put in enough effort to achieve said goal. In smaller groups, the impact one individual has is much greater, so individuals will be less inclined to free ride.

Modern thought

The most prominent modern interpretation of the collective action problem can be found in Mancur Olson's 1965 book The Logic of Collective Action.[5] In it, he addressed the accepted belief at the time by sociologists and political scientists that groups were necessary to further the interests of their members. Olson argued that individual rationality does not necessarily result in group rationality, as members of a group may have conflicting interests that do not represent the best interests of the overall group.

Olson further argued that in the case of a pure public good that is both nonrival and nonexcludable, one contributor tends to reduce their contribution to the public good as others contribute more. Additionally, Olson emphasized the tendency of individuals to pursue economic interests that would be beneficial to themselves and not necessarily the overall public. This contrasts with Adam Smith's theory of the "invisible hand" of the market, where individuals pursuing their own interests should theoretically result in the collective well-being of the overall market.[5]

Olson's book established the collective action problem as one of the most troubling dilemmas in social science, leaving a profound impression on present-day discussions of human behavior and its relationship with governmental policy.

In economics

Public goods

Public goods are goods that are nonrival and nonexcludable. A good is said to be nonrival if its consumption by one consumer does not in any way impact its consumption by another consumer. Additionally, a good is said to be nonexcludable if those who do not pay for the good cannot be kept from enjoying the benefits of the good.[6] The nonexcludability aspect of public goods is where one facet of the collective action problem, known as the free-rider problem, comes into play. For instance, a company could put on a fireworks display and charge an admittance price of $10, but if community members could all view the fireworks display from their homes, most would choose not to pay the admittance fee. Thus, the majority of individuals would choose to free ride, discouraging the company from putting on another fireworks show in the future. Even though the fireworks display was surely beneficial to each of the individuals, they relied on those paying the admittance fee to finance the show. If everybody had assumed this position, however, the company putting on the show would not have been able to procure the funds necessary to buy the fireworks that provided enjoyment for so many individuals. This situation is indicative of a collective action problem because the individual incentive to free ride conflicts with the collective desire of the group to pay for a fireworks show for all to enjoy.[6]

Pure public goods include services such as national defense and public parks that are usually provided by governments using taxpayer funds.[6] In return for their tax contribution, taxpayers enjoy the benefits of these public goods. In developing countries where funding for public projects is scare, however, it often falls on communities to compete for resources and finance projects that benefit the collective group.[7] The ability of communities to successfully contribute to public welfare depends on the size of the group, the power or influence of group members, the tastes and preferences of individuals within the group, and the distribution of benefits among group members. When a group is too large or the benefits of collective action are not tangible to individual members, the collective action problem results in a lack of cooperation that makes the provision of public goods difficult.[7]

Game theory

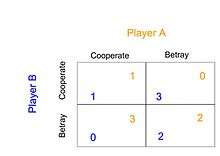

Game theory is one of the principal components of economic theory. It addresses the way individuals allocate scarce resources and how scarcity drives human interaction.[8] One of the most famous examples of game theory is the prisoner's dilemma. The classical prisoner's dilemma model consists of two players who are accused of a crime. If Player A decides to betray Player B, Player A will receive no prison time while Player B receives a substantial prison sentence, and vice versa. If both players choose to keep quiet about the crime, they will both receive reduced prison sentences, and if both players turn the other in, they will each receive more substantial sentences. It would appear in this situation that each player should choose to stay quiet so that both will receive reduced sentences. In actuality, however, players who are unable to communicate will both choose to betray each other, as they each have an individual incentive to do so in order to receive a commuted sentence.[9]

The prisoner's dilemma model is crucial to understanding the collective problem because it illustrates the consequences of individual interests that conflict with the interests of the group. In simple models such as this one, the problem would have been solved had the two prisoners been able to communicate. In more complex real world situations involving numerous individuals, however, the collective action problem often prevents groups from making decisions that are of collective economic interest.[10]

In politics

Voting

Scholars estimate that, even in a battleground state, there is only a one in ten million chance that one vote could sway the outcome of a United States presidential election.[11] This statistic may discourage individuals from exercising their democratic right to vote, as they believe they could not possibly affect the results of an election. If everybody adopted this view and decided not to vote, however, democracy would collapse. This situation results in a collective action problem, as any single individual is incentivized to choose to stay home from the polls since their vote is very unlikely to make a real difference in the outcome of an election.

Despite high levels of political apathy in the United States, however, this collective action problem does not decrease voter turnout as much as some political scientists might expect.[12] It turns out that most Americans believe their political efficacy to be higher than it actually is, stopping millions of Americans from believing their vote does not matter and staying home from the polls. Thus, it appears collective action problems can be resolved not just by tangible benefits to individuals participating in group action, but by a mere belief that collective action will also lead to individual benefits.

Environmental policy

Environmental problems such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and waste accumulation can be described as collective action problems.[13] Since these issues are connected to the everyday actions of vast numbers of people, vast numbers of people are also required to mitigate the effects of these environmental problems. Without governmental regulation, however, individual people or businesses are unlikely to take the actions necessary to reduce carbon emissions or cut back on usage of non-renewable resources, as these people and businesses are incentivized to choose the easier and cheaper option, which often differs from the environmentally-friendly option that would benefit the health of the planet.[13]

Individual self interest has led to over half of Americans believing that government regulation of businesses does more harm than good. Yet, when the same Americans are asked about specific regulations such as standards for food and water quality, most are satisfied with the laws currently in place or favor even more strident regulations.[14] This illustrates the way the collective problem hinders group action on environmental issues: when an individual is directly affected by an issue such as food and water quality, they will favor regulations, but when an individual cannot see a great impact from their personal carbon emissions or waste accumulation, they will generally tend to disagree with laws that encourage them to cut back on environmentally-harmful activities.

References

- ↑ "Collective action problem - Oxford Reference". doi:10.1093/acref/9780199670840.001.0001/acref-9780199670840-e-223. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ↑ Erhard Friedberg, "Conflict of Interest from the Perspective of the Sociology of Organized Action" in Conflict of Interest in Global, Public and Corporate Governance, Anne Peters & Lukas Handschin (eds), Cambridge University Press, 2012

- ↑ Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan.

- ↑ Hume, David. A Treatise of Human Nature.

- 1 2 Sandler, Todd (2015-09-01). "Collective action: fifty years later". Public Choice. 164 (3–4): 195–216. doi:10.1007/s11127-015-0252-0. ISSN 0048-5829.

- 1 2 3 "Public Goods: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics | Library of Economics and Liberty". www.econlib.org. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- 1 2 Banerjee, Abhijit (September 2006). "Public Action for Public Goods".

- ↑ "What is Game Theory?". levine.sscnet.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ "Game theory II: Prisoner's dilemma | Policonomics". policonomics.com. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ "The Collective Action Problem | GEOG 30N: Geographic Perspectives on Sustainability and Human-Environment Systems, 2011". www.e-education.psu.edu. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ "Voting matters even if your vote doesn't: A collective action dilemma". Princeton University Press Blog. 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ Kanazawa, Satoshi (2000). "A New Solution to the Collective Action Problem: The Paradox of Voter Turnout". American Sociological Review. 65 (3): 433–442. doi:10.2307/2657465. JSTOR 2657465.

- 1 2 Duit, Andreas (2011-12-01). "Patterns of Environmental Collective Action: Some Cross-National Findings". Political Studies. 59 (4): 900–920. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00858.x. ISSN 1467-9248.

- ↑ "A Majority Says that Government Regulation of Business Does More Harm than Good". Pew Research Center. 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2018-04-18.