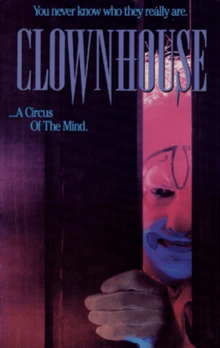

Clownhouse

| Clownhouse | |

|---|---|

Original trade advertisement | |

| Directed by | Victor Salva |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Victor Salva |

| Starring |

|

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography | Robin Mortarotti |

| Edited by |

|

Production company |

Commercial Pictures |

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 81 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $200,000 (estimated) |

Clownhouse is a 1989 American horror film written and directed by Victor Salva, starring Nathan Forrest Winters, Brian McHugh, and Sam Rockwell in his film debut. Its plot concerns three young brothers who are pursued by a group of three escaped mental patients disguised as clowns in the traveling circus.

Filmed in 1987, Clownhouse premiered at the 1989 Sundance Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize in the dramatic category, and received theatrical distribution in the United States in July 1990. Its release was controversial, as writer-director Salva pleaded guilty in 1988 to child sexual abuse of the film's star, Winters, as well as procuring child pornography of the sexual assault. Its release was protested by Winters and his family upon its theatrical release, and again in 2003 when it was released on DVD by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Home Entertainment, who pulled the title from shelves under public pressure.

Plot

Casey is an adolescent boy whose life is constantly influenced by his intense fear of clowns. His two older brothers, Geoffrey and Randy, are mostly disobliging. One night, the three boys are left alone when their mother visits relatives, so they decide to visit a local circus for a night of amusement, despite Casey's uncontrollable coulrophobia. Meanwhile, the local state insane asylum has sent a majority of the hospital's inmates to the carnival for therapy, but three psychotic mental patients break away from the group and kill three clowns, taking their makeup and costumes.

While at the circus, Casey innocently visits a fortune teller despite Randy's better judgment. The fortune teller reveals to Casey that his life line has been cut short, and says to him: "Beware, beware, in the darkest of dark /though the flesh is young and the hearts are strong /precious life cannot be long /when darkest death has left its mark."

As the boys return from the circus, a shaken Casey thinks his nightmare is over, but it has only just begun. When the clowns target their home, Casey is forced to face his fears once and for all. Casey and his brothers are locked inside their isolated farmhouse and the power is turned off. Casey attempts to call the police, but because Casey says that the "clowns from the circus are trying to get him", the police officers assume that Casey's fear of clowns caused him to have a realistic nightmare. The officers tell Casey that everything will be fine if he goes back to sleep, and hangs up.

Randy mockingly dresses up as a clown, disbelieving of Casey's claims that clowns are inside the house. His plan to jump out at Geoffrey and Casey is cut short after he is stabbed by one of the clowns. Geoffrey manages to kill the first clown by hitting him with a wooden plank, knocking him down a flight of stairs and breaking his neck.

Later on, after tricking the clown, Casey and Geoffrey push another clown out a window to his death. Casey and Geoffrey find Randy unconscious in a closet and drag him into another room. Geoffrey is then attacked and presumably killed by the final clown, who chases Casey into the upstairs game room. Casey manages to hide for the time being, but after the clown leaves, Casey accidentally steps on a noise-making toy, alerting the clown of his presence. The enraged clown attempts to break Casey's neck, but he is then killed by Geoffrey (who survived the clown's attack), slamming a hatchet into the killer's back, and the two exhausted and traumatized brothers hug each other as the police finally arrive to help them.

The film ends with this narration:

No man can hide from his fears; as they are a part of him, they will always know where he is hiding.

Cast

- Nathan Forrest Winters as Casey

- Brian McHugh as Geoffrey

- Sam Rockwell as Randy

- Tree as Lunatic Cheezo

- Bryan Weible as Lunatic Bippo

- David C. Reinecker as Lunatic Dippo

- Timothy Enos as Real Cheezo

- Frank Diamanti as Real Bippo

- Karl Heinz Teuber as Real Dippo

- Viletta Skillman as Mother

- Gloria Belsky as Fortune teller

- Tom Mottram as Ringmaster

Production

Impressed by Salva's 1986 short film Something in the Basement, Francis Ford Coppola gave him $250,000 to make Clownhouse.[1] To shoot the film, Coppola gave Salva the same cameras George Lucas had used to make American Graffiti (1973).[2]

Release

The film was shown at the Sundance Film Festival in January 1989,[3][2] and released theatrically on July 20, 1990.[lower-alpha 1]

Controversy

In 1988, director Victor Salva was convicted of the sexual abuse of Nathan Forrest Winters, the 12-year-old lead actor who played Casey, during production—including videotaping one of the encounters.[6] Commercial videotapes and magazines containing child pornography were also found at his home.[7] After serving 15 months of a three-year prison term, Salva was released on parole.[8]

Winters came forward again in 1995, when Salva's film Powder was released.[9][10][11] Winters picketed a screening in Westwood.[7]

In a YouTube interview conducted by Blastzone Mike with Winters on April 5, 2017, Winters revealed that when Salva was arrested, everything but the dubbing had been completed, and that all of the dialogue was added in post-production due to the extremely loud noise of the cameras. It's unclear whether or not Winters did his own dubbing.[12]

Critical response

Arlene Calkins of the Daily Utah Chronicle wrote that "This movie, for me, rivals anything I've seen done by Stephen King at his best... Salva's direction is crisp and right on the mark."[13] TV Guide gave the film two out of four stars, writing that the film "plays cleverly on the visceral dislike many people feel for clowns and the result is often truly creepy."[14] Joan Bunke of The Des Moines Register noted that the film "looks like a family-and-friends project... Salva... has cobbled together the usual outrageously phony horror flick plot," adding: "The fright-making shadows of Mortarotti's photography and the moody music underscoring the kids' horror of what is overtaking them helps blank out the irrationality of the plot."[5]

The film was included in a 2017 list of the "creepiest clowns in movies" compiled by Variety, in which it was noted: "The film’s claustrophobic setting and eerie atmosphere makes it one of the scariest thrillers on this list."[15]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 40% approval score based on 5 reviews, with an average rating of 5.7/10.[16]

Home media

Mainly due to the controversy during its production, Clownhouse became a sleeper hit, but soon fell into obscurity.[17] The film was released on VHS and Laserdisc in 1990. On August 26, 2003, the film was released on DVD by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer,[17] but was pulled from shelves due to protest surrounding the sex abuse incident that occurred during production.[18] It has since become a collector's item, with independent sellers retailing the disc for hundreds of dollars as of 2018.[19]

Notes

References

- ↑ Goldstein 2006, p. 3.

- 1 2 Goldstein 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Weinstein, Max (12 September 2015). "'Jeepers Creepers 3': An Offer We Can Refuse". Diabolique Magazine. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ↑ "Clownhouse: Now Showing". The Burlington Free Press. Burlington, Vermont. July 20, 1990. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Bunke, Joan (July 25, 1990). "'Clownhouse' needs more than white face to hide flaws". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. p. 40 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "A testimony to Hollywood's values". Chicago Tribune. Charleston, West Virginia Daily Mail. November 4, 1995. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Welkos, Robert (October 19, 1995). "Disney Movie's Director a Convicted Child Molester: Hollywood: He says, 'I paid for my mistakes dearly', but victim of incident several years ago urges boycott of 'Powder'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ Gannett, Jack (October 27, 1995). "'Powder' is a bit lightweight". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Zamora, Jim Herron (October 25, 1995). "Molest Victim Protests at Disney Film Release". The San Francisco Examiner. p. A-1. Retrieved December 21, 2012 – via Vacchs.com.

- ↑ Welkos, Robert W.; Brennan, Judy (October 31, 1995). "Dust Hasn't Settled on 'Powder'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 21, 2012 – via Vachss.com.

- ↑ Wells, Jeffrey (November 10, 1995). "A Question Disney Ducked; Should 'Powder' Have Been Desexed?". Entertainment Weekly. p. 37. Retrieved December 21, 2012 – via Vachss.com.

- ↑ Blastzone Mike - Nathan Forrest Winters he was molested by Victor Salva at the age of 6; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJgXSxXkj28

- ↑ Calkins, Arlene (January 19, 1989). "Park City festival offers variety of flicks". The Daily Utah Chronicle. Salt Lake City, Utah. pp. 8–9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Clownhouse Review". TV Guide. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ↑ "The 20 Creepiest Clowns in Movies and TV". Variety. 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Clownhouse (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- 1 2 Wallis, J. Doyle (August 7, 2003). "Clownhouse: DVD Talk Review". DVD Talk. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ Staff; Jason (October 5, 2015). "10 Underrated Horror Films That Probably Aren't on Your Watch List This Halloween But Totally Should Be". The Blood Shed. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ↑ "CLOWNHOUSE horror *DVD NEW RECALLED* clown SAM ROCKWELL cult 80's RARE". eBay. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

Works cited

- Goldstein, Patrick (June 11, 2006). "Victor Salva's horror stories". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 7, 2018.