Clonmany

| Clonmany Cluain Maine | |

|---|---|

| Village | |

| |

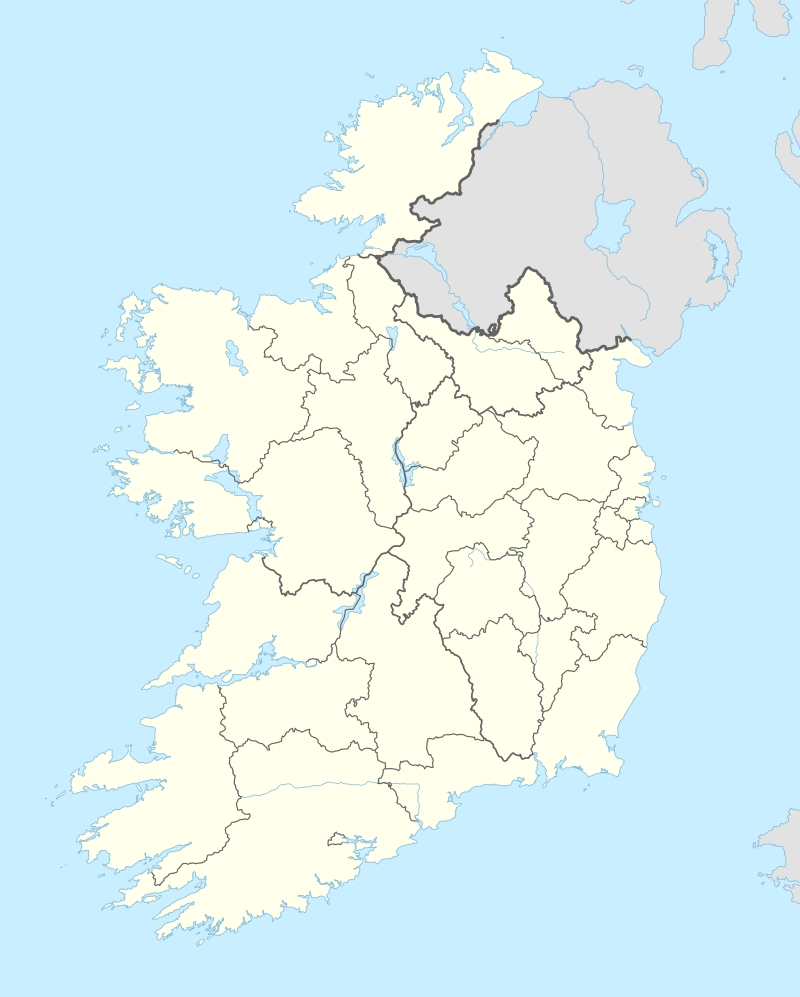

Clonmany Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 55°15′45″N 7°24′45″W / 55.2625°N 7.4125°WCoordinates: 55°15′45″N 7°24′45″W / 55.2625°N 7.4125°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Ulster |

| County | County Donegal |

| Government | |

| • Dáil Éireann | Donegal |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 95.01 km2 (36.68 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

| • Total | 428 |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-1 (IST (WEST)) |

| Area code(s) | 074, +353 74 |

| Irish Grid Reference | C374463 |

Clonmany (Irish: Cluain Maine)[3] is a village in north-west Inishowen, in County Donegal, Ireland. The area has many local beauty spots, while the nearby village of Ballyliffin is famous for its golf course. The Urris area to the west of Clonmany village was the last outpost of the Irish language in Inishowen. In the 19th century, the area was an important location for poitín distillation.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Name

The name of the town in Irish - Cluain Maine has been translated as both "The Meadow of St. Maine" and "The Meadow of the Monks", with the former being the more widely recognized translation. The village is known locally as "The Cross", as the village was initially built around a crossroads.

History

The Clonmany area is steeped in history, and dolmens, forts and standing stones dot the landscape. The parish was home to a monastery, closely associated with the Morrison family, who provided the role of erenagh. The monastery was home to the Míosach a copper and silver shrine, now located in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. Details of local history and traditions were recorded in "The Last of the Name", recorded by schoolteacher Patrick Kavanagh (NOT the poet) from stories by Clonmany local, Charles McGlinchey.

The village claims to be the youngest in Inishowen. It did not feature in the census of 1841 or 1851. In the 1861 census, 112 inhabitants are recorded as living in Clonmany in 21 houses. A further 3 houses are recorded as uninhabited.[4]

The Poitin Republic of Urris

In the early 19th century, Urris - a valley three miles west of Clonmany - became a center of the illegal poitín distillation industry. The Urris Hills were an ideal place for poitín-making. The area was surrounded by mountains and only accessible through Mamore Gap and Crossconnell. Notwithstanding its remote location, Derry was about 16 miles away, providing a major market for the trade. To protect their lucrative business, the locals barricaded the road at Crossconnell to keep out revenue police, thus creating the "Poitin Republic of Urris". This period of relative independence lasted three years. But in 1815, the authorities re-established control of the Urris Hills and brought this short period of self-rule and freedom to an end.[5][6]

The 1840 earthquake

In 1840, the village experienced an earthquake, a comparatively rare event in Ireland. The shock was also felt in the nearby town of Carndonagh. The Belfast Newsletter from Tuesday, January 28, 1840 reported that "In some places those who had retired to rest felt themselves shaken in their beds, and others were thrown from their chairs, and greatly alarmed."[7]

Land Wars in the 19th Century

Throughout the 19th century, the rural areas surrounding Clonmany experienced significant conflict over the issues of land ownership and tenant rights. During the 1830s, the Ribbon men were active in the area. This was a popular Catholic movement that protested against landlords and their agents. In February 1832, crowds of up to three thousand local tenants attacked the properties of two prominent landlords; Michael Doherty of Glen House and Neal Loughrey of Binnion. During the attacks, the protesters demanded a reduction in rents and the elimination of tithe payments to the Church of Ireland.[8][9] A similar incident occurred in June 1838, when a crowd of local peasants attacked the house where an absentee landlord was visiting during a trip to view their properties.[10] In 1838, during the latter years of the tithe war, the Roman Catholic parish priest of Clonmany - Fr. O'Donnell - was jailed for non-payment of tithes to the Church of Ireland.[11]

During the 1880s, evictions by landlords were relatively common events. The Land League established a Clonmany branch, which was named after the founder of the organization - Michael Davitt.[12] Its meetings were often reported by the Derry Journal. The newspaper recorded a steady flow of evictions of tenants throughout the 1880s.[13][14][15] The local Catholic clergy and Land League regularly pleaded the cases of individual tenants to local Landlords. In December 1885, The clergy and land league sent a deputation to Mr. Loughrey, a landlord who had a difficult relationship with his tenants. When the Land League representatives remarked on the low value of land, Mr. Loughrey was reported to reply "the tenants were too cheaply rented, that they wanted to drive me and my family to the workhouse, but I will take steps to draw a good many there along with me".[16] The Loughrey estate was one of the largest in the area.

Evictions were often met with met with opposition and organized protest. To avoid these protests, local landlords organized mass evictions, which took place on a single day, with a sizable police and military presence. This often meant that tenants had accumulated rent arrears for several years before the evictions actually took place. For example, on a single day In June 1881, a body of 80 armed police entered Clonmany with the objective of overseeing a series of evictions in the surrounding area. These evictions were collectively organized by four local landlords. A protest march was organized by the Land League and the local Priest - Fr. Maguire, who figured prominently in the opposition to evictions. However, on that day the evictions proved to be a tortuous process, with bailiffs poorly informed about the precise location of tenants, miss-identification of tenants and disputes about whether the rents had actually been paid or not.[17] In March 1882, the Derry Journal reported that a further 18 evictions had taken place on the Loughrey estate which made over 100 individuals homeless.[18]

The eviction of Catherine Doherty in August 1882 was very typical. She was a widow who lived in Cleagh, a townland just outside Clonmany. She had accumulated significant arrears before her landlord took legal proceedings against her. The Derry Journal recorded the event.

"The first house visited was that of widow Catherine Doherty. She owed two years’ rent. A writ was served on her May, 1881, Just two days after the rent became due. She tried to have a settlement effected but all in vain. She offered two years’ rent (£8 11s) with the half the costs, but that offer was flatly refused by the agent, who would accept nothing less than the entire amount of rent and costs, to be paid before he would leave the house. The Rev. Father O’Doherty, P.P., Father Maguire, and Father McCullagh were in attendance during the first eviction, and reasoned with Mr. Harvey for long time.

Men were ordered clear out the furniture. This occupied a considerable time. The usual formalities being gone through of binding up the doors, giving possession to the agent. The ranks of the soldiers and police were ordered (to) march to Rooskey, where the next eviction was (to) come off. Denis O’Donnell, three in family, was the tenant. His time of redemption having expired"[19]

In May 1883, Thomas Sexton (the Irish Nationalist MP for Sligo) asked a question in parliament regarding the conduct of the Royal Irish Constabulary towards evicted tenants in Clonmany. Mr. Sexton reported that a tenant farmer named Doherty was prevented by the police from erecting huts to shelter recently evicted families. He also reported that 23 families comprising 108 people had taken refuge in Clonmany with as many as four families sleeping into one small house. Sir George Trevelyan the Chief Secretary for Ireland, disputed this account. He reported that Doherty wanted to build his hut near some evicted farms, and this would require the Police to build an outpost to guard these farms. This construction would impose costs on the local community.[20]

Protests against evictions often targeted local individuals who had assisted in the process. In July 1888, seven local men were arrested and accused of interfering with the burial of Patrick Cavanagh. He was a former veteran of the Crimean War who worked on the Loughery estate. Cavanagh had become unpopular with the local residents after he became the caretaker of the properties of recently evicted tenants. The seven accused men were John O'Donnell, William Harkin, William Gubbin, Patrick Gubbln, Owen Doherty, from Clonmany; Constantine Doherty, from Cleagh; and Michael Doherty, from Cloontagh. The men were accused of filling up the newly dug grave with large stones and preventing the body from entering the graveyard. No one in the village was prepared to supply a coffin for Cavanagh. The local Catholic Clergy begged the demonstrators to allow the burial to proceed. The demonstrators threatened that if the body were buried in the graveyard that they would dig it up. Eventually, the Local Government Board issued an administrative order to remove the body for internment in the Carndonagh Workhouse cemetery.[21][22] The case aroused much interest and was reported widely across the United Kingdom.[23] Two of the accused - Owen Doherty and Constantine Doherty - were found guilty of unlawful assembly and sentenced to six months imprisonment. The remaining men were discharged.[24]

Irish War of Independence

In early 1920 an IRA company was established in Clonmany. It formed part of the 2nd Battalion of the Donegal IRA which was based on Carndonagh. The battalion also included companies from Culdaff, Malin, Malin Head and Carndonagh.[25]

In April 1921, Joseph Doherty, a farmer from Lenan, was found guilty during a court-martial for possessing firearms "not under effective military control." During a police search at the home of Doherty's mother, a single-barreled breech-loading shotgun was found concealed in a corn stack in the yard. Doherty made a statement to the Police indicating that he that knew nothing about the gun, which "must have been planted in the corn stack by someone who wished to get him into trouble." During the trial, Doherty refused to recognize the court. The presiding judge remarked that that accused's refusal to recognize the count had only one interpretation, that he belonged to an illegal society.[26]

The most notorious incident to occur in Clonmany during the conflict happened on 10 May 1921, when two Royal Irish Constabulary constables - Alexander Clarke and Charles Murdock - were kidnapped and murdered by the IRA. Both men were stationed at the RIC Barracks in Clonmany. They went on patrol in the evening but were kidnapped near Straid. Both men were shot and their bodies were dumped in the sea near Binion. The body of Clarke was washed up on the shore on seashore near Binion the next day. Constable Murdock reportedly survived the initial attack despite being thrown into the sea. He swam to the shore and sought refuge among residents of Binion. However, he was betrayed to the IRA who murdered him. His body has never been found. Local tradition suggests that he was buried in a bog near Binion hill.[27] In June 1921, a military court was held in Clonmany to conduct a postmortem for PC Clarke. The court found that Clarke had died from a gunshot wounds to the heart, jaw and neck and that his firearm and ammunition was missing. At the time of his death, Clarke was 23 years old and unmarried.[28]

A few weeks later, on July 10, 1921 Crown Forces raided a number of houses in Clonmany looking for Sinn Fein activists. Three unnamed young men from the village were arrested, but were released shortly afterwards and allowed to return home.[29]

Second World War

During the mid-20th century, a cottage based textiles industry had developed around Clonmany. During the war, many local women were contracted to make shirts for the British Army.[30] These contracts were allocated to cottage producers by firms in Buncrana and Derry that were unable to manage the large orders from the British War Office.

In August 1940, a body washed up on the shore at Gaddyduff, Clonmany. The body was recovered by Mr. Denis Kealey, a farmer's son, of Leenan. A postcard was found on the body indicating that the victim was Giovanni Ferdenzi ; an Italian migrant to the UK, who lived in Kings Cross. He was previously held at Worth-Mills Internment Camp. The cause of death was heart failure due to exposure. The body was given Catholic burial at Clonmany. Giovanni was being transported to Canada on SS Arandora Star, which was sunk by a a U-Boat on 2 July 1940. [31] A second unidentifiable body was washed ashore on Ballyliffin strand.[32]

In March 1946, eight mines were destroyed by the Irish Army after they had floated close to the shoreline between Ballyliffin and Clonmany. The mines appeared after a heavy storm.[33]

Floods

The village has periodically suffered from heavy flooding, typically after heavy rainfall during the summer months, In 2014, the National Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment Report highlighted Clonmany and its surrounding areas as one of 28 areas that may need flood protection as sea levels are expected to rise due to climate change.[34]

The 1892 Floods

On May 28, 1892, Clonmany experienced three hours of torrential rain, that caused the banks of the Clonmany river to break. Several hundred acres of land was flooded, with a large loss of crops and livestock. The townlands of Crossconnell. Tanderagee, Cleagh, Cloontagh, and Gortfad were all heavily flooded.[35]

The 1924 Floods

After a period of heavy rain during September 1952, the banks of the Clonmany river broke, flooding a number of corn fields. The area around Crossconnell was particularly affected.[36]

The 1952 Floods

In August 1952, the banks of the Clonmany river again broke after a period of very heavy rain. The rains coincided with a high tide, which further exacerbated the flood. Water reached the houses within the village itself.[37]

The 2017 Floods

In late August 2017, the village was severely affected by flooding brought on by an extended period of heavy rains. In a seven hour period, over 80 millimeters of rain was recorded.[38] Some residents were cut off due to rising river levels and had to be rescued from their homes. The R238 road, which links the village with Dumfree, was closed after a bridge collapsed.The Irish defense forces were deployed to help with rescue and clean up efforts.[39]

Climate

The location of Clonmany on the Inishowen peninsula, and bordering Lough Swilly with views of the Atlantic provides the Clonmany area with a moderate climate; with temperate, mild summers, and winters that rarely go below freezing. The average temperatures for the area are usually warmer than the national average in winter, and cooler than the national average in summer.

Education

Clonmany has four primary schools, Clonmany N.S. (with a new state of the art school), Scoil Naomh Treasa (also known as Tiernasligo N.S. locally), Scoil Phádraig at Rashenny, and Scoil na gCluainte, or Cloontagh National School. Most students from these schools go on to attend secondary level education at Carndonagh Community School in Carndonagh, with most of the remainder attending Scoil Mhuire or Crana College in Buncrana. There was a national school in Crossconnell, which dated from the 19th century. However, it was closed in the late 1960s.

Transport

Clonmany railway station opened on 1 July 1901, but finally closed on 2 December 1935.[40] The station was a stop on the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company (The L&LSR, the Swilly) that operated in parts of County Londonderry and County Donegal.

Culture & tourism

Clonmany is host to the annual McGlinchey summer school, which attracts many visitors to its exhibitions and lectures on local history. Another attraction is the Clonmany festival, held annually during the week of the Irish August public holiday. The Clonmany Agricultural Show and Sheepdog Trials takes place on the Tuesday of festival week, with visitors from all over Inishowen and the Northwest of Ireland.

Sports

The Clonmany Tug of War team has enjoyed remarkable success over many years. The team was formed in 1946, and has achieved six world gold medals and twenty All Ireland titles.[41]

See also

References

- ↑ Census 2002 - Volume 1: Population Classified By Area, Central Statistics Office, Dublin, 2003

- ↑ "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements Clonmany". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ "Cluain Maine/Clonmany". Placenames Database of Ireland. Government of Ireland - Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht and Dublin City University. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ "Parish Census 1841,1851 and 1861". Clonmany. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ https://dailyscribbling.com/the-odd-side-of-donegal/the-poitin-republic-of-urris/

- ↑ Atkinson, David; Roud, Steve (2016). Street Ballads in Nineteenth-Century Britain, Ireland, and North America: The Interface Between Print and Oral Traditions. London: Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781317049210.

- ↑ Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938, Tuesday, January 28, 1840; Page: 4

- ↑ "Whiteboyism in Ennishowen". Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail. 4 February 1832.

- ↑ "Donegal Assizes". Enniskillen Chronicle and Erne Packet. 2 August 1832.

- ↑ "Irish Outrages". Freemans Journal. June 15, 1838.

- ↑ "The tithe curse— A catholic clergyman incarcerated in the north". Freemans Journal. August 1838.

- ↑ "Clonmany (Davitt) Branch". Derry Journal. 21 October 1885.

- ↑ "Ladies Land League, Clonmany Donegal". Derry Journal. 1 June 1881.

- ↑ "Clonmany (Country Donegal) Branch, Land League". Derry Journal. 1 June 1881.

- ↑ "Irish National League, Clonmany Branch". Derry Journal. 10 June 1885.

- ↑ "Irish National League, Clonmany Branch". Derry Journal. 9 December 1885.

- ↑ "Evictions in Clonmany". Derry Journal. 22 June 1881.

- ↑ "The evictions in Donegal". Derry Journal. 24 March 1882.

- ↑ "Evictions in Clonmnay, County Donegal". Derry Journal. 21 August 1882.

- ↑ Hansard's Parliamentary Debates. London. 1883. p. 699.

- ↑ "Burial prevented in Ireland". St James's Gazette. 30 June 1888.

- ↑ "Boycotting a Corpse". Northern Constitution. 21 July 1888.

- ↑ "Refusing a corpse to be buried". Glasgow Evening Citizen. 29 June 1888.

- ↑ "BARBAROUS CONDUCT. NO BETTER THAN SAVAGES". Londonderry Sentinel. 19 July 1888.

- ↑ ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1516.

- ↑ "GUN IN CORN STACK. TRIAL OF DONEGAL. FARMER. DECLINES TO RECOGNISE COURT". Ballymena Weekly Telegraph. 16 April 1921.

- ↑ "MURDERED AND THROWN INTO SEA. FATE OF DONEGAL CONSTABLES". Northern Whig. 11 May 1921.

- ↑ "Recent Clonmany tragedy - findings of military court". Fermanagh Herald 1. June 11, 1921.

- ↑ "Military Raids in Clonmany". Derry Journal. 13 July 1921.

- ↑ "Cottage made shirts for Troops". Irish Press 1. March 8, 1940.

- ↑ "Inquest on Arandora Star victims". Irish Press. August 14, 1940.

- ↑ "Catholic Burial". Donegal Democrat. August 14, 1940.

- ↑ "Mines ashore in Donegal". Irish Independent. March 7, 1946.

- ↑ "Twenty-eight areas at risk of flooding - report". Donegal News. February 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Great Floods in Innishowen". Derry Journal. 30 May 1892.

- ↑ "Flooding in Clonmany District". Derry Journal. September 26, 1924.

- ↑ "Cloudburst in Clonmany". Donegal News. August 23, 1952.

- ↑ "INISHOWEN FLOODING: 'MIRACLE' ESCAPES ON A PENINSULA DEVASTATED". Donegal Daily. August 2017.

- ↑ "Minister says emergency agency should be set up as army pitches in for second day in Donegal". The Journal.IE. August 2017.

- ↑ "Clonmany station" (PDF). Railscot - Irish Railways. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ↑ "Clonmany Tug of War Team: A History - 50 Years on". Clonmany. Retrieved 3 July 2017.