Cleopatra (1963 film)

| Cleopatra | |

|---|---|

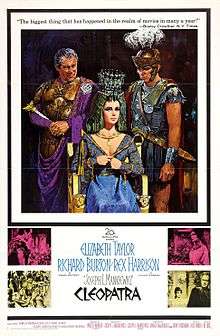

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joseph L. Mankiewicz |

| Produced by | Walter Wanger |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

The Life and Times of Cleopatra by C.M. Franzero Histories by Plutarch, Suetonius, and Appian |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Alex North |

| Cinematography | Leon Shamroy |

| Edited by | Dorothy Spencer |

| Distributed by | Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 248 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $31.1 million[3] |

| Box office | $57.8 million (US)[4] |

Cleopatra is a 1963 American epic historical drama film chronicling the struggles of Cleopatra, the young Queen of Egypt, to resist the imperial ambitions of Rome. It was directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, with a screenplay adapted by Mankiewicz, Ranald MacDougall and Sidney Buchman from a book by Carlo Maria Franzero. The film stars Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Rex Harrison, Roddy McDowall, and Martin Landau.

Cleopatra achieved notoriety during its production for its massive cost overruns and production troubles, which included changes in director and cast, a change of filming locale, sets that had to be constructed twice, lack of a firm shooting script, and personal scandal around co-stars Taylor and Burton. It was the most expensive film ever made up to that point and almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox.

It was the highest-grossing film of 1963, earning box-office of $57.7 million in the United States (equivalent to $461 million in 2017), yet lost money due to its production and marketing costs of $44 million (equivalent to $352 million in 2017), making it the only film ever to be the highest-grossing film of the year to run at a loss.[5] Cleopatra later won four Academy Awards, and was nominated for five more, including Best Picture (which it lost to Tom Jones).

Plot

After the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, where Julius Caesar (Rex Harrison) has defeated Pompey in a brutal civil war for control of the Roman Republic, Pompey flees to Egypt, hoping to enlist the support of the young Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII (Richard O'Sullivan) and his sister Cleopatra (Elizabeth Taylor). Caesar follows him to Egypt, under the pretext of being named the executor of the will of their father, Ptolemy XII. Much to his dismay, Caesar is given Pompey's head as a gift, as the highly manipulated pharaoh was convinced by his chief eunuch Pothinus (Gregoire Aslan) that this act would endear him to Caesar.

As Caesar stays in one of the palaces, a slave named Apollodorus (Cesare Danova) brings him a gift. When the suspicious Caesar unrolls the rug, he finds Cleopatra herself concealed within. He is intrigued with her beauty and warm personality, and she convinces him to restore her throne from her younger brother.

Soon after, Cleopatra warns Caesar that her brother has surrounded the palace with his soldiers and that he is vastly outnumbered. Counterattacking, he orders the Egyptian fleet burned so he can gain control of the harbor. The fire spreads to the city, destroying the famous Library of Alexandria. Cleopatra angrily confronts Caesar, but he refuses to pull troops away from the fight with Ptolemy's forces to quell the fire. In the middle of their spat, Caesar forcefully kisses her.

The Romans hold, and the armies of Mithridates arrive on Egyptian soil, causing Ptolemy's offensive to collapse. The following day, Caesar is in effective control of the kingdom. He sentences Pothinus to death for arranging an assassination attempt on Cleopatra, and banishes Ptolemy to the eastern desert, where he and his outnumbered army would face certain death against Mithridates. Cleopatra is crowned Queen of Egypt. She begins to develop megalomaniacal dreams of ruling the world with Caesar, who in turn desires to become king of Rome. They marry, and when their son Caesarion is born, Caesar accepts him publicly, which becomes the talk of Rome and the Senate.

After he is made dictator for life, Caesar sends for Cleopatra. She arrives in Rome in a lavish procession and wins the adulation of the Roman people. The Senate grows increasingly discontented amid rumors that Caesar wishes to be made king, which is anathema to the Romans. On the Ides of March in 44 BC, the Senate is preparing to vote on whether to award Caesar additional powers. A group of conspirators assassinate Caesar and flee the city, starting a rebellion. An alliance between Octavian, Caesar's adopted son, Mark Antony, Caesar's right-hand man and general as well as Marcus Ameilius Lepidus put down the rebellion and split up the republic between themselves. However, a rivalry between Octavian and Antony is becoming apparent. Cleopatra is angered after Caesar's will recognizes Octavian instead of Caesarion as his official heir, and angrily returns to Egypt.

While planning a campaign against Parthia in the east, Antony realizes he needs money and supplies, and cannot get enough from anywhere but Egypt. After refusing several times to leave Egypt, Cleopatra gives in and meets him in Tarsus. Antony becomes drunk during a lavish feast. Cleopatra sneaks away, leaving a slave dressed as her, but Antony discovers the trick and confronts the queen. The two begin a love affair, with Cleopatra assuring Anthony that he is much more than a pale reflection of Caesar.

Octavian's removal of Lepidus forces Anthony to return to Rome, where he marries Octavian's sister, Octavia, to prevent conflict. When news of this reaches Cleopatra, she is distraught and enraged. Anthony's new marriage leaves him dissatisfied, and logistical needs force him to meet with Cleopatra. The two reconcile and marry, with Anthony divorcing Octavia. Octavian, incensed, reads Anthony's will to the Roman senate, revealing that the latter wishes to be buried in Egypt. Shocked by his lack of patriotism, Rome turns against Anthony, and Octavian's call for war against Egypt receives a rapturous response.

The war is decided at the naval Battle of Actium on September 2, 31 BC where Octavian's fleet, under the command of Agrippa, defeats the Antony-Egyptian fleet. In the midst of the battle, with Antony's ship on fire, Cleopatra assumes he is dead and orders the Egyptian forces home. Antony follows, leaving his fleet leaderless and soon defeated.

Several months later, Cleopatra manages to convince Antony to retake command of his troops and fight Octavian's advancing army. However, Antony's soldiers have lost faith in him and abandon him during the night; Rufio (Martin Landau), the last man loyal to Antony, kills himself. Antony tries to goad Octavian into single combat, but is finally forced to flee into the city.

Octavian and his army march into Alexandria with Caesarion's dead body in a wagon. Octavian has taken Caesarion's ring, which his mother gave him earlier as a parting gift when she sent him to safety.

When Antony returns to the palace, Apollodorus, not believing that Antony is worthy of his queen, convinces him that she is dead, whereupon Antony falls on his own sword. Apollodorus then confesses that he misled Antony and assists him to the tomb where Cleopatra and two servants have taken refuge. Antony dies of his wounds soon after.

Octavian seizes the palace and discovers the dead body of Apollodorus, who had poisoned himself. Octavian receives word that Antony is dead and Cleopatra is holed up in a tomb. Octavian sees her and after some verbal sparring offers her his word that he will spare her, return her possessions, and allow her to rule Egypt as a Roman province in return for her agreeing to accompany him to Rome. She observes Caesarion's ring on Octavian's hand and inquires after her son. When Octavian denies any knowledge of his whereabouts and pledges to allow him to rule Egypt in his mother's absence, Cleopatra knows her son is dead and that Octavian's word is without value. She agrees to Octavian's terms, including a pledge not to harm herself, sworn on the life of her dead son. After Octavian departs, she orders her servants in coded language to assist with her suicide.

She sends her servant Charmion to give Octavian a letter. In the letter she asks to be buried with Antony. Octavian realizes that she is going to kill herself and he and his guards burst into Cleopatra's chamber and find her dressed in gold, and dead, along with her servant Eiras, while an asp crawls along the floor.

Charmion is found kneeling next to the altar on which Cleopatra is lying, and Agrippa asks of her: "Was this well done of your lady?" She replies: "Extremely well. As befitting the last of so many noble rulers." She then falls dead as Agrippa watches.

Cast

- Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra

- Richard Burton as Mark Antony

- Rex Harrison as Julius Caesar

- Roddy McDowall as Octavian, alias Augustus

- Martin Landau as Rufio

- Hume Cronyn as Sosigenes

- George Cole as Flavius

- Carroll O'Connor as Servilius Casca

- Andrew Keir as Agrippa

- Gwen Watford as Calpurnia

- Kenneth Haigh as Brutus

- Pamela Brown as the High Priestess

- Cesare Danova as Apollodorus

- Robert Stephens as Germanicus

- Francesca Annis as Eiras

- Richard O'Sullivan as Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII

- Gregoire Aslan as Pothinus

- Martin Benson as Ramos

- John Cairney as Phoebus

- Andrew Faulds as Canidius

- Michael Gwynn as Cimber

- Michael Hordern as Cicero

- John Hoyt as Cassius

- Marne Maitland as Euphranor

- Douglas Wilmer as Decimus

- Jean Marsh as Octavia Minor (uncredited)

- Desmond Llewelyn as a Roman senator (uncredited)

- Peter Grant as a palace guard (uncredited)

Production

As the story of Cleopatra had proved a hit in 1917 for silent-screen legend Theda Bara, and was remade in 1934 with Claudette Colbert, 20th Century Fox executives hired veteran Hollywood producer Walter Wanger in 1958 to shepherd another remake of Cleopatra into production. Although the studio originally sought a relatively cheap production of $2 million, Wanger envisioned a much more opulent epic, and in mid-1959 successfully negotiated a higher budget of $5 million. Rouben Mamoulian was assigned to direct and Elizabeth Taylor was awarded a record-setting contract of $1 million. Filming began in England but in January 1961 Taylor became so ill that production was shut down. Sixteen weeks of production and costs of $7 million had produced just ten minutes of film. Fox was reimbursed by the insurance company and Mamoulian was fired.[6]

Joseph L. Mankiewicz was brought on to the production after Mamoulian's departure and the set moved to Cinecittà, outside of Rome. Peter Finch and Stephen Boyd left the production owing to other commitments and were replaced by Rex Harrison and Richard Burton, as Julius Caesar and Mark Anthony respectively. During filming, Taylor met Burton and the two began an adulterous affair; the scandal made headlines worldwide, since both were married to others, and brought bad publicity to the already troubled production. Mankiewicz was later fired during the editing phase, only to be rehired to reshoot the opening battle scenes in Spain.[6]

The cut of the film which Mankiewicz screened for the studio was six hours long. This was cut to four hours for its initial premiere, but the studio demanded (over the objections of Mankiewicz) that the film be cut once more, this time to just barely over three hours to allow theaters to increase the number of showings per day.[7] Mankiewicz unsuccessfully attempted to convince the studio to split the film in two in order to preserve the original cut. These were to be released separately as Caesar and Cleopatra followed by Antony and Cleopatra.[6]

Cleopatra ended up costing $31 million, making it the most expensive film ever made at the time,[3] and almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox.[5]

Soundtrack

The music of Cleopatra was scored by Alex North. It was released several times, first as an original album, and later versions were extended. The most popular of these was the Deluxe Edition or 2001 Varèse Sarabande album.

Reception

A reviewer for Time said, "As drama and as cinema, Cleopatra is riddled with flaws. It lacks style both in image and in action."[8] Judith Crist concurred, calling it "a monumental mouse".[9] Even star Elizabeth Taylor found it wanting, saying, "They had cut out the heart, the essence, the motivations, the very core, and tacked on all those battle scenes. It should have been about three large people, but it lacked reality and passion. I found it vulgar."[10]

Positive reactions came from such publications as Variety, which wrote, "Cleopatra is not only a supercolossal eye-filler (the unprecedented budget shows in the physical opulence throughout), but it is also a remarkably literate cinematic recreation of an historic epoch."[8] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called it "one of the great epic films of our day".[11]

Retrospective reviews have been more forgiving towards it. American film critic Emanuel Levy said, "Much maligned for various reasons, [...] Cleopatra may be the most expensive movie ever made, but certainly not the worst, just a verbose, muddled affair that is not even entertaining as a star vehicle for Taylor and Burton."[8] Billy Mowbray for the website of British television channel Film4 remarked that the film is "A giant of a movie that is sometimes lumbering, but ever watchable thanks to its uninhibited ambition, size and glamour."[8]

At an audience level the film was a major hit, grossing $57.8 million in the United States and Canada,[4] and in the process became the most successful film of 1963.[12] Despite the film's popularity, however, Fox's income of $40.3 million earned from its share of the global ticket sales was not enough to cover the film's $44 million costs. Fox eventually recouped its investment in 1966 when it sold the television broadcast rights to ABC.[13]

Awards and nominations

The film won four Academy Awards and was nominated for five more.[14][15] It also earned Elizabeth Taylor a Guinness World Record title, "Most costume changes in a film"; Taylor made 65 costume changes. This record was beaten in 1996 in the film Evita by Madonna with 85 costume changes.

50th Anniversary restored version

Schawn Belston, serving as senior vice president of library and technical services for 20th Century Fox, was put in charge of creating a restored version of the film for the company. After a two-year process in 2013 he was able to restore a four-hour, eight-minute version. One of Belston's finds for this version was the original camera negative which was shot on 65mm. (Any longer version, which has yet to be found, would have existed only to show then-studio boss Darryl F. Zanuck.) Fading and damage to the negative were corrected digitally with an eye on preserving detail and authenticity while avoiding digital manipulation.[16] Belston's team also had the original magnetic print masters which they used to restore the sound. They removed the clicks and hisses, then with the aid of the trained ears of musicians reconfigured the track for 5.1 surround sound.[16]

On May 21, 2013, the restored film was shown at a special screening at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, to commemorate its 50th anniversary.[17] It was later released as a 50th-anniversary version available on DVD and Blu-ray. Unfortunately Fox had long ago destroyed all of the trims and outs from negatives to save costs, preventing the release of traditional outtakes. The home media packages did include commentary tracks and two short films: "The Cleopatra Papers" and a 1963 film about the elaborate sets "The Fourth Star of Cleopatra".[16]

See also

References

- ↑ "CLEOPATRA (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. 1963-05-30. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "Catalog of Feature Films: Cleopatra". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- 1 2 Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen (2010). Epics, spectacles, and blockbusters: a Hollywood history. Wayne State University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8143-3008-1.

With top tickets set at an all-time high of $5.50,Cleopatra had amassed as much as $20 million in such guarantees from exhibitors even before its premiere. Fox claimed the film had cost in total $44 million, of which $31,115,000 represented the direct negative cost and the rest distribution, print and advertising expenses. (These figures excluded the more than $5 million spent on the production's abortive British shoot in 1960–61, prior to its relocation to Italy.) By 1966 worldwide rentals had reached $38,042,000 including $23.5 million from the United States.

- 1 2 "Cleopatra (1963)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- 1 2 John Patterson "Cleopatra, the film that killed off big-budget epics", The Guardian, 15 July 2013

- 1 2 3 Gachman, Dina (2010). "Cleopatra". In Block, Alex Ben; Wilson, Lucy Autrey. George Lucas's Blockbusting: A Decade-by-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success. HarperCollins. pp. 460–461. ISBN 9780061778896.

- ↑ Cleopatra from Johnny Web

- 1 2 3 4 "Cleopatra (1963)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ↑ "1963: Movies as Art". Columbia Journalism School.

- ↑ Rice, E. Lacey. "Cleopatra (1963)". Turner Classic Movies.

- ↑ Burns, Kevin; Zacky, Brent. "Cleopatra: The Film That Changed Hollywood." American Movie Classics. 3 April 2001. Television.

- ↑ "All Time Box Office: Domestic Grosses – Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ↑ Block, Alex Ben; Wilson, Lucy Autrey, eds. (2010). George Lucas's Blockbusting: A Decade-by-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success. HarperCollins. pp. 434 & 461. ISBN 9780061778896.

- ↑ "The 36th Academy Awards (1964) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-23.

- ↑ "Cleopatra (1963)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- 1 2 3 Atkinson, Nathalie (May 21, 2013). "Queen of the Nile: Inside 20th Century Fox's restoration of Cleopatra". National Post.

- ↑ Rosser, Michael; Wiseman, Andreas (29 April 2013). "Cannes Classics 2013 line-up unveiled". Screen Daily. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- Cleopatra: The Film That Changed Hollywood, a 2001 television documentary

- Ilias Chrissochoidis (ed.), The Cleopatra Files: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive (Stanford, 2013).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cleopatra (1963 film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cleopatra (1963 film) |

- Cleopatra on IMDb

- Cleopatra at the TCM Movie Database

- Cleopatra at Box Office Mojo

- Cleopatra at Rotten Tomatoes

.jpg)