Claus Schilling

| Claus Karl Schilling | |

|---|---|

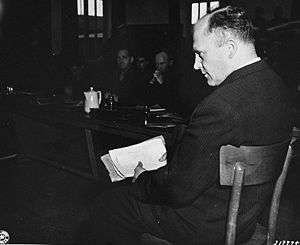

Claus Schilling sitting before a tribunal in November 1945 | |

| Born |

5 July 1871 Munich, Germany |

| Died |

28 May 1946 (aged 74) Landsberg am Lech, Allied-occupied Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Tropical medicine, medical research |

Claus Karl Schilling (5 July 1871, Munich, Bavaria, Germany – 28 May 1946, Landsberg am Lech, Bavaria, West Germany), also recorded as Klaus Schilling, was a German tropical medicine specialist who participated in the Nazi human experiments at the Dachau concentration camp during World War II.

Though never a member of the Nazi Party and a recognized researcher before the war, Schilling became notorious as a consequence of his unethical and inhuman participation in human research under both Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. From 1942 to 1945, Schilling's research of malaria and attempts at fighting it using synthetic drugs resulted in over a thousand cases of human experimentation on camp prisoners.

Sentenced to death by hanging after the fall of Hitler's Germany, he was executed for his crimes against the Dachau prisoners in 1946.

Biography

Born in Munich on July 5, 1871, Schilling studied medicine in his native city, receiving a doctor's degree there in 1895. He was a professor of parasitology at the University of Berlin and a member of Malaria Commission of the League of Nations[1]. Within a few years, Schilling was practicing in the German colonial possessions in Africa. Recognized for his contributions in the field of tropical medicine, he was appointed the first-ever director of the tropical medicine division of the Robert Koch Institute in 1905, where he would remain for the subsequent three decades.

Italian research

Upon retirement from the Robert Koch Institute in 1936, Schilling moved to Benito Mussolini's Fascist Italy, where he was given the opportunity to conduct immunization experiments on inmates of the psychiatric asylums of Volterra and San Niccolò di Siena.[2] (The Italian authorities were concerned that troops faced malaria outbreaks in the course of the Italo-Ethiopian War.) As Schilling stressed the significance of the research for German interests, the Nazi government of Germany also supported him with a financial grant for his Italian experimentation.[2]

Dachau experiments

Schilling returned to Germany after a meeting with Leonardo Conti, the Nazis' Health Chief, in 1941, and by early 1942 he was provided with a special malaria research station at Dachau's concentration camp by Heinrich Himmler, the leader of the SS. Despite negative assessments from colleagues, Schilling would remain in charge of the malaria station for the duration of the war.[2]

Although in the 1930s Schilling had stressed the point that malaria research on human subjects could be performed in an entirely harmless fashion, the Dachau subjects included prisoners who were injected with synthetic drugs at doses ranging from high to lethal. They had been exposed to malaria mosquitos in cages strapped to their hands or arms so as to ensure infection with the parasite. Of the more than 1,000 prisoners used in the malaria experiments at Dachau during the war, between 300 and 400 died as a result; among survivors, a substantial number remained permanently damaged. A number of priests imprisoned by the Nazis were killed during the experiments.[2]

In the course of the Dachau Trials following the liberation of the camp at the close of the war, Schilling was tried by a U.S. General Military Court, appointed at November 2, 1945, in the case of The United States versus Martin Gottfried Weiss, Wilhelm Rupert, et al. The defendants, 40 doctors and staff, were charged and convicted of offenses of the violations of laws and usages of war in that they acted in pursuance of a common design, did encourage, aid, abet, and participate in the subjection of Allied nationals and prisoners of war to cruelties and mistreatments at Dachau Concentration Camp and its subcamps.[3] According to the August H. Vieweg testimony, the patients used in the malaria experiments were Poles, Russians, and Yugoslavs[3]. That time there was no formal code of ethics in medical research to which the judges could hold the accused Nazi doctors accountable. The "scientific experiments" exposed during the trials lead to the Nuremberg Code, developed in 1949 as a ten-point code of human experimentation ethics[4].

The tribunal sentenced Schilling to death by hanging on December 13, 1945. His execution took place at Landsberg Prison in Landsberg am Lech on May 28, 1946.

References

- ↑ Marcus J. Smith: Dachau: The Harrowing of Hell, SUNY Press, 2012, ISBN 9781438420325 p. 178

- 1 2 3 4 Hulverscheidt, Marion. "German Malariology Experiments with Humans, Supported by the DFG Until 1945". Man, Medicine, and the State: The Human Body as an Object of Government Sponsored Medical Research in the 20th Century, Beiträge zur Geschichte der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft Volume 2. Ed. Wolfgang Uwe Eckhart. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2006. ISBN 3-515-08794-X, ISBN 978-3-515-08794-0, pp. 221–236.

- 1 2 Spitz, Vivien. Doctors from Hell: The Horrific Account of Nazi Experiments on Humans. Boulder, Colorado: Sentient Publications, 2005. ISBN 1-59181-032-9, ISBN 978-1-59181-032-2, p. 104-112.

- ↑ Christine Grady: The Search for an AIDS Vaccine: Ethical Issues in the Development and Testing of a Preventive HIV Vaccine, Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 9780253112729, p. 35