Clark Terry

| Clark Terry | |

|---|---|

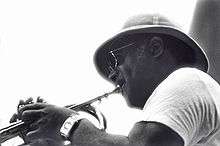

Terry at the 1981 Monterey Jazz Festival | |

| Background information | |

| Born |

December 14, 1920 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died |

February 21, 2015 (aged 94) Pine Bluff, Arkansas |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1940s–2015 |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts |

|

| Website |

clarkterry |

Clark Virgil Terry Jr.[1] (December 14, 1920 – February 21, 2015) was an American swing and bebop trumpeter, a pioneer of the flugelhorn in jazz, composer, educator, and NEA Jazz Masters inductee.[2]

He played with Charlie Barnet (1947), Count Basie (1948–51),[3] Duke Ellington (1951–59),[3] Quincy Jones (1960), and Oscar Peterson (1964-96). He was also with The Tonight Show Band from 1962 to 1972. Terry's career in jazz spanned more than 70 years, during which he became one of the most recorded jazz musicians ever, appearing on over 900 recordings. Terry also mentored many musicians including Quincy Jones, Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Wynton Marsalis, Pat Metheny, Dianne Reeves, and Terri Lyne Carrington among thousands of others.[4]

Early life

Terry was born to Clark Virgil Terry Sr. and Mary Terry in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 14, 1920.[1][3] He attended Vashon High School and began his professional career in the early 1940s, playing in local clubs. He served as a bandsman in the United States Navy during World War II. His first instrument was valve trombone.[5]

Big band era

Blending the St. Louis tone with contemporary styles, Terry's years with Basie and Ellington in the late 1940s and 1950s established his prominence. During his period with Ellington, he took part in many of the composer's suites and acquired a reputation for his wide range of styles (from swing to hard bop), technical proficiency, and good humor. Terry influenced musicians including Miles Davis and Quincy Jones, both of whom acknowledged Terry's influence during the early stages of their careers. Terry had informally taught Davis while they were still in St Louis,[6] and Jones during Terry's frequent visits to Seattle with the Count Basie Sextet.[7]

After leaving Ellington in 1959, Clark's international recognition soared when he accepted an offer from the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) to become a staff musician. He appeared for ten years on The Tonight Show as a member of the Tonight Show Band until 1972, first led by Skitch Henderson and later by Doc Severinsen, where his unique "mumbling" scat singing led to a hit with "Mumbles".[8] Terry was the first African American to become a regular in a band on a major US television network. He said later: "We had to be models, because I knew we were in a test.... We couldn't have a speck on our trousers. We couldn't have a wrinkle in the clothes. We couldn't have a dirty shirt."[9]

Terry continued to play with musicians such as trombonist J. J. Johnson and pianist Oscar Peterson,[10] and led a group with valve-trombonist Bob Brookmeyer that achieved some success in the early 1960s. In February 1965, Brookmeyer and Terry appeared on BBC2's Jazz 625.[11] and in 1967, presented by Norman Granz, he was recorded at Poplar Town Hall, in the BBC series Jazz at the Philharmonic, alongside James Moody, Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Teddy Wilson, Bob Cranshaw, Louie Bellson and T-Bone Walker.[12]

In the 1970s, Terry concentrated increasingly on the flugelhorn, which he played with a full, ringing tone. In addition to his studio work and teaching at jazz workshops, Terry toured regularly in the 1980s with small groups (including Peterson's) and performed as the leader of his Big B-A-D Band (formed about 1970). After financial difficulties forced him to break up the Big B-A-D Band, he performed with bands such as the Unifour Jazz Ensemble. His humor and command of jazz trumpet styles are apparent in his "dialogues" with himself, on different instruments or on the same instrument, muted and unmuted.

Later career

From the 1970s through the 1990s, Terry performed at Carnegie Hall, Town Hall, and Lincoln Center, toured with the Newport Jazz All Stars and Jazz at the Philharmonic, and was featured with Skitch Henderson's New York Pops Orchestra. In 1998, Terry recorded George Gershwin's "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off" for the Red Hot Organization's compilation album Red Hot + Rhapsody, a tribute to George Gershwin, which raised money for various charities devoted to increasing AIDS awareness and fighting the disease.

In the 1980s he was a featured soloist performing in front of the band. In November 1980, he was a headliner along with Anita O'Day, Lionel Hampton and Ramsey Lewis during the opening two-week ceremony performances celebrating the short-lived resurgence of the Blue Note Lounge at the Marriott O'Hare Hotel near Chicago.

Prompted early in his career by Billy Taylor, Clark and Milt Hinton bought instruments for and gave instruction to young hopefuls, which planted the seed that became Jazz Mobile in Harlem. This venture tugged at Terry's greatest love: involving youth in the perpetuation of jazz. From 2000 onwards, he hosted Clark Terry Jazz Festivals on land and sea, held his own jazz camps, and appeared in more than fifty jazz festivals on six continents. Terry composed more than two hundred jazz songs and performed for eight U.S. Presidents.[13]

He also had several recordings with major groups including the London Symphony Orchestra, the Dutch Metropole Orchestra, and the Chicago Jazz Orchestra, hundreds of high school and college ensembles, his own duos, trios, quartets, quintets, sextets, octets, and two big bands: Clark Terry's Big Bad Band and Clark Terry's Young Titans of Jazz. The Clark Terry Archive at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey, contains instruments, tour posters, awards, original copies of over 70 big band arrangements, recordings and other memorabilia.

In February 2004, Terry guest starred as himself, on Little Bill, a children's television series. Terry was a resident of Bayside, Queens, and Corona, Queens, New York, later moving to Haworth, New Jersey, and then Pine Bluff, Arkansas.[14][15]

His autobiography was published in 2011[4] and, as Taylor Ho Bynum writes in The New Yorker, "captures his gift for storytelling and his wry humor, especially in chronicling his early years on the road, with struggles through segregation and gigs in juke joints and carnivals, all while developing one of most distinctive improvisational voices in music history."[16]

In April 2014, a documentary Keep on Keepin' On, follows Clark Terry over four years to document the mentorship between Terry, and 23-year-old blind piano prodigy Justin Kauflin, as the young man prepares to compete in an elite, international competition.[17]

According to his own website Terry was "one of the most recorded jazz artists in history and had performed for eight American Presidents."[18]

In December 2014 the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis and Cécile McLorin Salvant visited Terry, who had celebrated his 94th birthday on December 14, at the Jefferson Regional Medical Center. A lively rendition of "Happy Birthday" was played.[19]

Death and tributes

On February 13, 2015, it was announced that Terry had entered hospice care to manage his advanced diabetes.[20] He died on February 21, 2015.[21][22]

Writing in The New York Times, Peter Keepnews said Terry "was acclaimed for his impeccable musicianship, loved for his playful spirit and respected for his adaptability. Although his sound on both trumpet and the rounder-toned flugelhorn (which he helped popularize as a jazz instrument) was highly personal and easily identifiable, he managed to fit it snugly into a wide range of musical contexts."[23]

Writing in UK's The Daily Telegraph, Martin Chilton said: "Terry was a music educator and had a deep and lasting influence on the course of jazz. Terry became a mentor to generations of jazz players, including Miles Davis, Wynton Marsalis and composer-arranger Quincy Jones."[9]

Interviewing Terry in 2005, fellow jazz trumpeter Scotty Barnhart said he was "... one of the most incredibly versatile musicians to ever live ... a jazz trumpet master that played with the greatest names in the history of the music ..."[24]

Southeast Missouri State University hosts the Clark Terry/Phi Mu Alpha Jazz Festival, an annual tribute to the musician. The festival began in 1998, and has grown in size every year. The festival showcases outstanding student musicians and guest artists at the university's River Campus.[25][26]

Awards and honors

Over 250 awards, medals and honors, including:

- Inducted into the Jazz at Lincoln Center Nesuhi Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame (2013)[27]

- The 2010 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, two Grammy certificates, three Grammy nominations[28]

- Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame[29]

- The National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Award (1991)[30]

- In 1988, Terry received an Honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music. [31]

- Sixteen honorary doctorates[32]

- Keys to several cities[33]

- Jazz Ambassador for U.S. State Department tours in the Middle East and Africa[34]

- A knighthood in Germany[35]

- Charles E. Lutton Man of Music Award, presented by Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia Fraternity in (1985). Terry was awarded honorary membership in the Fraternity by the Beta Zeta Chapter at the College of Emporia (1968). He was also made an honorary member of the Iota Phi chapter of Kappa Kappa Psi, National Honorary Band Fraternity (2011).

- The French Order of Arts and Letters (2000)[36]

- A life-sized wax figure for the Black World History Museum in St. Louis

- Inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame (1996)[37]

- NARAS Present's Merit Award (2005)[38]

- Trumpeter of the Year by the Jazz Journalists Association (2005)[32]

Discography

As leader or co-leader

- Clark Terry (EmArcy, 1955)

- Serenade to a Bus Seat (Riverside, 1957)

- Out on a Limb with Clark Terry (Argo, 1957)

- Duke with a Difference (Riverside, 1957)

- In Orbit (with Thelonious Monk, Riverside, 1958)

- Top and Bottom Brass (Riverside, 1959)

- Tate-a-Tate (Swingville, 1960)

- Paris, 1960 (Swing, 1960)

- Color Changes (Candid, 1960)

- Everything's Mellow (Moodsville, 1961)

- Previously Unreleased Recordings (Verve, 1961 [1974])

- Clark Terry Plays the Jazz Version of All American (Moodsville, 1962)

- Eddie Costa: Memorial Concert (Colpix, 1962)

- Back in Bean's Bag (Columbia, 1963)

- 3 in Jazz (RCA, 1963)

- More (Theme from Mondo Cane) (Cameo, 1963)

- What Makes Sammy Swing (20th Century Fox, 1963)

- Tread Ye Lightly (Cameo, 1963)

- Oscar Peterson Trio + One (Verve, 1964) with Oscar Peterson

- The Happy Horns of Clark Terry (Impulse!, 1964)

- Live 1964 (Emerald, 1964)

- Tonight (with Bob Brookmeyer, Mainstream, 1964)

- The Power of Positive Swinging (with Bob Brookmeyer, Mainstream, 1965)

- Mumbles (Mainstream, 1966)

- Gingerbread Men (with Bob Brookmeyer, Mainstream, 1966)

- Soul Duo (with Shirley Scott, Impulse!, 1966)

- Spanish Rice (Impulse!, 1966)

- It's What's Happenin' (Impulse!, 1967)

- Music in the Garden (Jazz Heritage, 1968)

- Clark Terry at the Montreux Jazz Festival (Polydor, 1969)

- Live at the Wichita Jazz Festival (Vanguard, 1974)

- Oscar Peterson and Clark Terry (Pablo, 1975)

- Oscar Peterson and the Trumpet Kings – Jousts (Pablo, 1975)

- Clark Terry and His Jolly Giants (Vanguard, 1976)

- Live at the Jazz House (Pausa, 1976)

- Wham (BASF, 1976)

- Squeeze Me (Chiaroscuro, 1976)

- Clark Terry's Big Bad Band Live on 57th Street (Big Bear, 1976)

- Clark Terry's Big B-A-D Band Live at Buddy's... (Vanguard, 1977)

- The Globetrotter (Vanguard, 1977)

- Out of Nowhere (Bingow, 1978)

- Brahms Lullabye (Amplitude, 1978)

- Funk Dumplin's (Matrix, 1978)

- Clark After Dark (MPS, 1978)

- The Effervescent (JazzTime, Jazz Greats, 1978)

- Mother ! Mother ! (Pablo, 1979)

- Ain't Misbehavin' (Pablo, 1979)

- Live in Chicago, Vol. 1 (Monad, 1979)

- Live in Chicago, Vol. 2 (Monad, 1979)

- The Trumpet Summit Meets the Oscar Peterson Big 4 (Pablo, 1980)

- Memories of Duke (Pablo Today, 1980)

- Yes, the Blues (Pablo, 1981)

- Jazz at the Philharmonic – Yoyogi National Stadium, Tokyo 1983: Return to Happiness (1983)

- To Duke and Basie (Rhino, 1986)

- Jive at Five (Enja, 1986)

- Metropole Orchestra (Mons, 1988)

- Portraits (Chesky, 1988)

- The Clark Terry Spacemen (Chiaroscuro, 1989)

- Locksmith Blues (Concord Jazz, 1989)

- Having Fun (Delos, 1990)

- Live at the Village Gate (Chesky, 1990)

- Live at the Village Gate: Second Set (Chesky, 1990)

- What a Wonderful World: For Lou (Red Baron, 1993)

- Shades of Blues (Challenge, 1994)

- Remember the Time (Mons, 1994)

- With Pee Wee Claybrook & Swing Fever (D'Note, 1995)

- Top and Bottom Brass (Chiaroscuro, 1995)

- Reunion (D'Note, 1995)

- Express (Reference, 1995)

- Good Things in Life (Mons, 1996)

- Ow (E.J.s) (1996)

- The Alternate Blues (Analogue, 1996)

- Ritter der Ronneburg (Mons, 1998)

- One on One (Chesky, 2000)

- A Jazz Symphony (Centaur, 2000)

- Creepin' with Clark (with Mike Vax) (Summit, 2000)

- Herr Ober: Live at Birdland Neuburg (Nagel-Heyer, 2001)

- Live on QE2 (Chiaroscuro, 2001)

- Jazz Matinee (Hanssler] 2001)

- The Hymn (Candid, 2001)

- Clark Terry and His Orchestra Featuring Paul Gonsalves [1959] (Storyville, 2002)

- Live in Concert (Image, 2002)

- Flutin' and Fluglin (Past Perfect, 2002)

- Friendship (Columbia, 2002)

- Live! At Buddy's Place (Universe, 2003)

- Live at Montmartre June 1975 (Storyville, 2003)

- George Gershwin's Porgy & Bess (A440 Music Group, 2004)

- Live at Marian's with the Terry's Young Titans of Jazz (Chiaroscuro, 2005)

As sideman

With Gene Ammons

- Soul Summit Vol. 2 (Prestige, 1961 [1962])

- Late Hour Special (Prestige, 1961 [1964])

- Velvet Soul (Prestige, 1961 [1964])

With Dave Bailey

- One Foot in the Gutter (Epic, 1960)

- Gettin' Into Somethin' (Epic, 1961)

- Afro-Jaws (Riverside, 1960)

- Trane Whistle (Prestige, 1960)

With Duke Ellington

- Ellington Uptown (Columbia, 1952)

- Premiered by Ellington (Capitol, 1953)

- Dance to the Duke! (Capitol, 1954)

- Ellington '55 (Capitol, 1955)

- Ellington Showcase (Capitol, 1955)

- Blue Rose (Columbia, 1956)

- A Drum Is a Woman (Columbia, 1956)

- Ellington at Newport (Columbia, 1956)

- Such Sweet Thunder (Columbia, 1957)

- Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Duke Ellington Song Book (Verve, 1957)

- All Star Road Band (Doctor Jazz, 1957 [1983])

- Ellington Indigos (Columbia, 1958)

- Black, Brown and Beige (Columbia, 1958)

- Duke Ellington at the Bal Masque (Columbia, 1958)

- The Cosmic Scene (Columbia, 1958)

- Festival Session (Columbia, 1959)

- The Ellington Suites (Columbia, 1959)

- Blues in Orbit (Columbia, 1960)

- The Greatest Jazz Concert in the World (1967)

With Stan Getz

- Big Band Bossa Nova (Verve, 1962)

- Stan Getz Plays Music from the Soundtrack of Mickey One (MGM, 1965)

With Dizzy Gillespie

- Gillespiana (Verve, 1960)

- Carnegie Hall Concert (Verve, 1961)

- The Trumpet Kings Meet Joe Turner (Pablo, 1974)

- The Trumpet Summit Meets the Oscar Peterson Big 4 (Pablo, 1980)

With Johnny Griffin

- The Big Soul-Band (Riverside, 1960)

- White Gardenia (Riverside, 1961)

With Jimmy Hamilton

- It's About Time (Swingville, 1961)

With Johnny Hodges

- Creamy (Norgran, 1955)

- Ellingtonia '56 (Norgran, 1956)

- Duke's in Bed (Verve, 1956)

- The Big Sound (Verve, 1957)

With Milt Jackson

- Big Bags (Riverside, 1962)

- For Someone I Love (Riverside, 1963)

- Ray Brown / Milt Jackson with Ray Brown (Verve, 1965)

With J. J. Johnson

- J.J.! (RCA Victor, 1964)

- Goodies (RCA Victor, 1965)

- Concepts in Blue (Pablo Today, 1981)

With Quincy Jones

- The Birth of a Band! (Mercury, 1959)

- I Dig Dancers (Mercury, 1960)

- Big Band Bossa Nova (Mercury, 1962)

- Quincy Jones Plays Hip Hits (Mercury, 1963)

- Quincy Jones Explores the Music of Henry Mancini (Mercury, 1964)

- Quincy Plays for Pussycats (Mercury, 1959-65 [1965])

- The Hot Rock OST (Prophesy, 1972)

With Mundell Lowe

- Themes from Mr. Lucky, The Untouchables and Other TV Action Jazz (RCA Camden, 1960)

- Satan in High Heels (soundtrack) (Charlie Parker, 1961)

With Herbie Mann

- Latin Fever (Atlantic, 1963)

- My Kinda Groove (Atlantic, 1964)

- Our Mann Flute (Atlantic, 1966)

- The Beat Goes On (Atlantic, 1967)

- The Herbie Mann String Album (Atlantic, 1967)

With Gary McFarland

- The Jazz Version of "How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying" (Verve, 1962)

- Tijuana Jazz (Impulse!, 1965)

With Charles Mingus

- Pre-Bird/Mingus Revisited/ (Mercury/Limelight, 1960 [reissue, 1965])

- The Complete Town Hall Concert (Blue Note, 1962 [1994])

With Blue Mitchell

- Smooth as the Wind (1961)

- A Sure Thing (1962)

With Gerry Mulligan

- Gerry Mulligan and the Concert Jazz Band at the Village Vanguard (Verve, 1960)

- Gerry Mulligan '63 (Verve, 1963)

With Oliver Nelson

- Impressions of Phaedra (United Artists Jazz, 1962)

- Full Nelson (Verve, 1962)

- Oliver Nelson Plays Michelle (Impulse!, 1966)

- Happenings (Impulse!, 1966)

- Encyclopedia of Jazz (Verve, 1966)

- The Sound of Feeling (Verve, 1966)

- The Spirit of '67 (Impulse!, 1967)

With Dave Pike

- Bossa Nova Carnival (New Jazz, 1962)

- Jazz for the Jet Set (Atlantic, 1966)

With Gene Roland

- Swingin' Friends (Brunswick, 1963)

With Sonny Rollins

With Lalo Schifrin

- New Fantasy (Verve, 1964)

- Once a Thief and Other Themes (Verve, 1965)

With Sonny Stitt

- The Matadors Meet the Bull (Roulette, 1965)

- I Keep Comin' Back! (Roulette, 1966)

With Billy Taylor

- Taylor Made Jazz (Argo, 1959)

- Kwamina (Mercury, 1961)

With others

- Ernestine Anderson, My Kinda Swing (Mercury, 1960)

- George Barnes, Guitars Galore (Mercury, 1961)

- George Benson, Goodies (Verve, 1968)

- Willie Bobo, Bobo's Beat (Roulette, 1962)

- Bob Brookmeyer, Gloomy Sunday and Other Bright Moments (Verve, 1961)

- Clifford Brown, Jam Session (EmArcy, 1954)

- Ruth Brown, Ruth Brown '65 (Mainstream, 1965)

- Kenny Burrell, Lotsa Bossa Nova (Kapp, 1963)

- Gary Burton, Who Is Gary Burton? (RCA, 1962)

- Charlie Byrd, Byrd at the Gate (Riverside, 1963)

- Al Caiola, Cleopatra and All That Jazz (United Artists, 1963)

- Al Cohn, Son of Drum Suite (RCA Victor, 1960)

- Tadd Dameron, The Magic Touch (1962)

- Art Farmer, Listen to Art Farmer and the Orchestra (Mercury, 1962)

- Ella Fitzgerald, Ella Abraça Jobim (Pablo, 1981)

- Paul Gonsalves, Cookin' (Argo, 1957)

- Dave Grusin, Homage to Duke (1993)

- Chico Hamilton, The Further Adventures of El Chico (Impulse!, 1966)

- Lionel Hampton, You Better Know It!!! (Impulse!, 1965)

- Jimmy Heath, Really Big! (Riverside, 1960)

- John Hicks, Friends Old and New (Novus, 1992)

- Kenyon Hopkins, The Yellow Canary (Verve, 1960)

- Budd Johnson, Budd Johnson and the Four Brass Giants (Riverside, 1960)

- Elvin Jones, Summit Meeting (Vanguard, 1976)

- Sam Jones, Down Home (Riverside, 1962)

- Lambert, Hendricks & Bavan, At Newport '63 (RCA, 1963)

- Yusef Lateef, The Centaur and the Phoenix (Riverside, 1960)

- Michel Legrand, Michel Legrand Plays Richard Rodgers (Philips, 1962)

- Abbey Lincoln, The World Is Falling Down (Polydor S.A./Verve, 1990)

- Junior Mance, The Soul of Hollywood (Jazzland, 1962)

- Modern Jazz Quartet, Jazz Dialogue (Atlantic, 1965)

- Mark Murphy, That's How I Love the Blues! (Riverside, 1962)

- Chico O'Farrill, Nine Flags (Impulse!, 1966)

- Oscar Pettiford, Basically Duke (Bethlehem, 1954)

- Jimmy Smith, Hobo Flats (Verve, 1963)

- Cecil Taylor, New York City R&B (Candid, 1961)

- Ed Thigpen, Out of the Storm (Verve, 1966)

- Teri Thornton, Devil May Care (Riverside, 1961)

- Stanley Turrentine, Joyride (Blue Note, 1965)

- McCoy Tyner, Live at Newport (Impulse, 1964)

- Dinah Washington, Dinah Jams (EmArcy, 1954)

- Randy Weston, Uhuru Afrika (Roulette, 1960)

- Joe Williams, At Newport '63 (RCA, 1963)

- Gerald Wilson, New York, New Sound (Mack Avenue, 2003)

- Kai Winding, Kai Olé (Verve, 1961)

- Jimmy Woode, The Colorful Strings of Jimmy Woode (Argo, 1957)

See also

Bibliography

- Let's Talk Trumpet: From Legit to Jazz (with Phil Rizzo), 1973

- Clark Terry's System of Circular Breathing for Woodwind and Brass Instruments (with Phil Rizzo), 1975

- Interpretation of the Jazz Language, Bedford, Ohio: M. A. S. Publishing Company, 1977

- TerryTunes, anthology of 60 original compositions (1st edn, 1972; 2nd edn w/doodle-tonguing chapter, 2009)

- "Clark Terry – Jazz Ambassador: C.T.'s Diary" [cover portrait], Jazz Journal International 31 (May 6, 1978): pp. 7–8.

- "Jazz for the Record" [Clark Terry Archive at William Paterson University], The New York Times (December 11, 2004).

- Beach, Doug, "Clark Terry and the St. Louis Trumpet Sound", Instrumentalist 45 (April 1991): 8–12.

- Bernotas, Bob, "Clark Terry", Jazz Player 1 (October–November 1994): 12–19.

- Blumenthal, Bob, "Reflections on a Brilliant Career" [reprint of JazzTimes 25, No. 8], Jazz Educators Journal 29, No. 4 (1997): 30–33, 36–37.

- Ellington, Duke, "Clark Terry" chapter in Music is My Mistress (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973): 229–230.

- LaBarbera, John, "Clark Terry: More Than 'Mumbles'", ITG Journal (International Trumpet Guild) 19, No. 2 (1994): 36–41.

- Morgenstern, Dan, "Clark Terry" in Living With Jazz: A Reader (New York: Pantheon, 2004): 196–201. [Reprint of Down Beat 34 (June 1, 1967): 16–18.]

- Owens, Thomas, "Trumpeters: Clark Terry", in Bebop: The Music and the Players (New York: Oxford, 1995): 111–113.

- Terry, C. Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry, University of California Press (2011), ISBN 978-0520268463

References

- 1 2 "Clark Terry (1920–2015)". The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ↑ "NEA Jazz Masters | NEA". Arts.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-21.

- 1 2 3 Yanow, Scott Clark Terry biography at Allmusic.

- 1 2 Terry, C. Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry, University of California Press (2011).

- ↑ Stephen Graham. "Clark Terry has died". Marlbank. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Trumpeter Clark Terry Shares Jazz Memories". NPR.org. January 1, 2005. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Quincy (1993). "Newport 1958". In Tucker, Mark. The Duke Ellington Reader. Oxford University Press. pp. 311–312. ISBN 0-19-509391-7.

- ↑ Adam Bernstein (February 22, 2015). "Clark Terry, jazz virtuoso with Basie, Ellington and 'Tonight Show,' dies". Washington Post. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- 1 2 Martin Chilton (February 22, 2015). "Clark Terry, jazz trumpeter, dies aged 94". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ Oscar Peterson and Clark Terry at AllMusic

- ↑ "Tribute to Bob Brookmeyer". clarkterry.com. December 19, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Jazz at the Philharmonic - Library of Congress". loc.gov. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Clark Terry: NVLP: African American History". visionaryproject.org. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ Berman, Eleanor, "The jazz of Queens encompasses music royalty", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 1, 2006. Accessed October 1, 2009. "When the trolley tour proceeds, Mr. Knight points out the nearby Dorie Miller Houses, a co-op apartment complex in Corona where Clark Terry and Cannonball and Nat Adderley lived and where saxophonist Jimmy Heath still resides."

- ↑ Potter, Beth. "Haworth's Notable Characters", Haworth, New Jersey. Accessed June 22, 2010.

- ↑ Taylor Ho Bynum, "The Sound of Musical Joy: Clark Terry's Trumpet", The New Yorker, February 24, 2015.

- ↑ trandall517 (April 19, 2014). "Keep on Keepin' On (2014)". IMDb. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ↑ Neela Debnath (February 22, 2015). "Clark Terry dead: Grammy-winning trumpet player dies aged 94". The Independent. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Happy 94th Birthday CLARK TERRY!". YouTube. 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2016-08-21.

- ↑ Marc Schneider (February 13, 2015). "Jazz Great Clark Terry Enters Hospice Care". Billboard. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ↑ THR Staff, Marc Schneider, Billboard (February 21, 2015). "Jazz Musician Clark Terry Dies at 94". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- ↑ Daniel Kreps (February 22, 2015). "Jazz Great Clark Terry Dead at 94". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ Peter Keepnews (February 22, 2015). "Clark Terry, Master of Jazz Trumpet, Dies at 94". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ↑ Barnhart, Scotty (2005). The World of Jazz Trumpet: A Comprehensive History & Practical Philosophy. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0634095276. Chapter 3: Clark Terry, pp. 91-96.

- ↑ http://www.semo.edu/admissions/aboutsoutheast/history.html

- ↑ http://www.semo.edu/music/festivals/jazz.html

- ↑ Jazz at Lincoln Center's Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame. "Art Blakey, Lionel Hampton, and Clark Terry inducted into Jazz at Lincoln Center's Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame". jalc.org/. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Jazz Trumpeter Clark Terry Dies". GRAMMY.com. 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ "DownBeat Archives". downbeat.com. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ "NEA Jazz Masters | NEA". www.arts.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ https://jazztimes.com/news/clark-terry-1920-2015/

- 1 2 "Quincy Jones | Interviews with Clark Terry: Trumpeter, Composer, Mentor. In Memoriam. | American Masters | PBS". American Masters. 2015-02-25. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ Terry, Clark; Terry, Gwen (2011-09-01). Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520268463.

- ↑ Barnhart, Scotty (2005-01-01). The World of Jazz Trumpet: A Comprehensive History & Practical Philosophy. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 9780634095276.

- ↑ Michael Juk (April 23, 2012). "Clark Terry's jazz trumpeter heart touches Vancouverites". CBC Music. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "AT THE MOVIES". The New York Times. 2000-03-10. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Arkansas Artists - Arkansas Entertainers - Famous Arkansans". www.arkansas.com. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clark Terry. |

- Terry's Official Website

- Terry at Allmusic

- "Profile: Clark Terry" by Arnold Jay Smith (www.jazz.com)

- Clark Terry's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Clark Terry Interview NAMM Oral History Library (2008)