Circulant graph

In graph theory, a circulant graph is an undirected graph that has a cyclic group of symmetries which takes any vertex to any other vertex. It is sometimes called a cyclic graph,[1] but this term also is given other meanings.

Equivalent definitions

Circulant graphs can be described in several equivalent ways:[2]

- The automorphism group of the graph includes a cyclic subgroup that acts transitively on the graph's vertices. In other words, the graph has a graph automorphism, which is a cyclic permutation of its vertices.

- The graph has an adjacency matrix that is a circulant matrix.

- The n vertices of the graph can be numbered from 0 to n − 1 in such a way that, if some two vertices numbered x and (x +d) mod n are adjacent, then every two vertices numbered z and (z +d) mod n are adjacent.

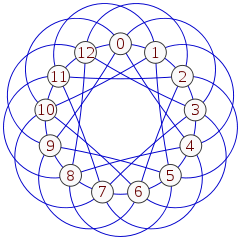

- The graph can be drawn (possibly with crossings) so that its vertices lie on the corners of a regular polygon, and every rotational symmetry of the polygon is also a symmetry of the drawing.

- The graph is a Cayley graph of a cyclic group.[3]

Examples

Every cycle graph is a circulant graph, as is every crown graph with 2 modulo 4 vertices.

The Paley graphs of order n (where n is a prime number congruent to 1 modulo 4) is a graph in which the vertices are the numbers from 0 to n − 1 and two vertices are adjacent if their difference is a quadratic residue modulo n. Since the presence or absence of an edge depends only on the difference modulo n of two vertex numbers, any Paley graph is a circulant graph.

Every Möbius ladder is a circulant graph, as is every complete graph. A complete bipartite graph is a circulant graph if it has the same number of vertices on both sides of its bipartition.

If two numbers m and n are relatively prime, then the m × n rook's graph (a graph that has a vertex for each square of an m × n chessboard and an edge for each two squares that a chess rook can move between in a single move) is a circulant graph. This is because its symmetries include as a subgroup the cyclic group Cmn Cm×Cn. More generally, in this case, the tensor product of graphs between any m- and n-vertex circulants is itself a circulant.[2]

Many of the known lower bounds on Ramsey numbers come from examples of circulant graphs that have small maximum cliques and small maximum independent sets.[1]

A specific example

The circulant graph with jumps is defined as the graph with nodes labeled where each node i is adjacent to 2k nodes .

- The graph is connected if and only if .

- If

are fixed integers then the number of spanning trees

where

satisfies a recurrence relation of order

.

- In particular, where is the n-th Fibonacci number.

Self-complementary circulants

A self-complementary graph is a graph in which replacing every edge by a non-edge and vice versa produces an isomorphic graph. For instance, a five-vertex cycle graph is self-complementary, and is also a circulant graph. More generally every Paley graph is a self-complementary circulant graph.[4] Horst Sachs showed that, if a number n has the property that every prime factor of n is congruent to 1 modulo 4, then there exists a self-complementary circulant with n vertices. He conjectured that this condition is also necessary: that no other values of n allow a self-complementary circulant to exist.[2][4] The conjecture was proven some 40 years later, by Vilfred.[2]

Ádám's conjecture

Define a circulant numbering of a circulant graph to be a labeling of the vertices of the graph by the numbers from 0 to n − 1 in such a way that, if some two vertices numbered x and y are adjacent, then every two vertices numbered z and (z − x + y) mod n are adjacent. Equivalently, a circulant numbering is a numbering of the vertices for which the adjacency matrix of the graph is a circulant matrix.

Let a be an integer that is relatively prime to n, and let b be any integer. Then the linear function that takes a number x to ax + b transforms a circulant numbering to another circulant numbering. András Ádám conjectured that these linear maps are the only ways of renumbering a circulant graph while preserving the circulant property: that is, if G and H are isomorphic circulant graphs, with different numberings, then there is a linear map that transforms the numbering for G into the numbering for H. However, Ádám's conjecture is now known to be false. A counterexample is given by graphs G and H with 16 vertices each; a vertex x in G is connected to the six neighbors x ± 1, x ± 2, and x ± 7 modulo 16, while in H the six neighbors are x ± 2, x ± 3, and x ± 5 modulo 16. These two graphs are isomorphic, but their isomorphism cannot be realized by a linear map.[2]

Algorithmic questions

There is a polynomial-time recognition algorithm for circulant graphs, and the isomorphism problem for circulant graphs can be solved in polynomial time.[5][6]

References

- 1 2 Small Ramsey Numbers, Stanisław P. Radziszowski, Electronic J. Combinatorics, dynamic survey 1, updated 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vilfred, V. (2004), "On circulant graphs", in Balakrishnan, R.; Sethuraman, G.; Wilson, Robin J., Graph Theory and its Applications (Anna University, Chennai, March 14–16, 2001), Alpha Science, pp. 34–36 .

- ↑ Alspach, Brian (1997), "Isomorphism and Cayley graphs on abelian groups", Graph symmetry (Montreal, PQ, 1996), NATO Adv. Sci. Inst. Ser. C Math. Phys. Sci., 497, Dordrecht: Kluwer Acad. Publ., pp. 1–22, MR 1468786 .

- 1 2 Sachs, Horst (1962). "Über selbstkomplementäre Graphen". Publicationes Mathematicae Debrecen. 9: 270–288. MR 0151953. .

- ↑ Muzychuk, Mikhail (2004). "A Solution of the Isomorphism Problem for Circulant Graphs". Proc. London Math. Soc. 88: 1–41. doi:10.1112/s0024611503014412. MR 2018956.

- ↑ Evdokimov, Sergei; Ponomarenko, Ilia (2004). "Recognition and verification of an isomorphism of circulant graphs in polynomial time". St. Petersburg Math. J. 15: 813–835. doi:10.1090/s1061-0022-04-00833-7. MR 2044629.