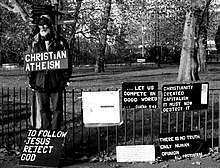

Christian atheism

Christian atheism is a form of cultural Christianity and ethics system drawing its beliefs and practices from Jesus' life and teachings as recorded in the New Testament Gospels and other sources, whilst rejecting supernatural claims of Christianity.

Christian atheism takes many forms: some Christian atheists take a theological position in which the belief in the transcendent or interventionist God is rejected or absent in favor of finding God totally in the world (Thomas J. J. Altizer) while others follow Jesus in a godless world (William Hamilton). Hamilton's Christian atheism is similar to Jesuism.

Beliefs

Thomas Ogletree, Frederick Marquand Professor of Ethics and Religious Studies at Yale Divinity School, lists these four common beliefs:[1][2]

- The assertion of the unreality of God for our age, including the understandings of God which have been a part of traditional Christian theology.

- The insistence upon coming to grips with contemporary culture as a necessary feature of responsible theological work.

- Varying degrees and forms of alienation from the church as it is now constituted.

- Recognition of the centrality of the person of Jesus in theological reflection.

God's existence

According to Paul van Buren, a Death of God theologian, the word God itself is "either meaningless or misleading".[2] Van Buren contends that it is impossible to think about God and says:

We cannot identify anything which will count for or against the truth of our statements concerning 'God'.[2]

The inference from these claims to the "either meaningless or misleading" conclusion is implicitly premised on the verificationist theory of meaning. Most Christian atheists believe that God never existed, but there are a few who believe in the death of God literally.[3] Thomas J. J. Altizer is a well-known Christian atheist who is known for his literal approach to the death of God. He often speaks of God's death as a redemptive event. In his book The Gospel of Christian Atheism, he says:

Every man today who is open to experience knows that God is absent, but only the Christian knows that God is dead, that the death of God is a final and irrevocable event and that God's death has actualized in our history a new and liberated humanity.[4]

Dealing with culture

Theologians including Altizer and Lyas looked at the scientific, empirical culture of today and tried to find religion's place in it. In Altizer's words:

No longer can faith and the world exist in mutual isolation…the radical Christian condemns all forms of faith that are disengaged with the world.[4]

He goes on to say that our response to atheism should be one of "acceptance and affirmation".[4] Colin Lyas, a Philosophy lecturer at Lancaster University, stated:

Christian atheists are united also in the belief that any satisfactory answer to these problems must be an answer that will make life tolerable in this world, here and now and which will direct attention to the social and other problems of this life.[3]

Separation from the church

Thomas Altizer has said:

[T]he radical Christian believes that the ecclesiastical tradition has ceased to be Christian.[4]

Altizer believed that orthodox Christianity no longer had any meaning to people because it did not discuss Christianity within the context of contemporary theology. Christian atheists want to be completely separated from most orthodox Christian beliefs and biblical traditions.[5] Altizer states that a faith will not be completely pure if it is open to modern culture. This faith "can never identify itself with an ecclesiastical tradition or with a given doctrinal or ritual form". He goes on to say that faith cannot "have any final assurance as to what it means to be a Christian".[4] Altizer said: "We must not, he says, seek for the sacred by saying 'no' to the radical profanity of our age, but by saying 'yes' to it".[5] They see religions which withdraw from the world as moving away from truth. This is part of the reason why they see the existence of God as counter-progressive. Altizer wrote of God as the enemy to man because mankind could never reach its fullest potential while God existed.[4] He went on to state that "to cling to the Christian God in our time is to evade the human situation of our century and to renounce the inevitable suffering which is its lot".[4]

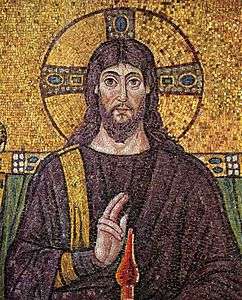

Centrality of Jesus

Although Jesus is still a central feature of Christian atheism, Hamilton said that to the Christian atheist, Jesus as an historical or supernatural figure is not the foundation of faith; instead, Jesus is a "place to be, a standpoint".[5] Christian atheists look to Jesus as an example of what a Christian should be, but they do not see him as God, nor as the Son of God; merely as an influential rabbi.

Hamilton wrote that following Jesus means being "alongside the neighbor, being for him"[5] and that to follow Jesus means to be human, to help other humans, and to further humankind.

Other Christian atheists such as Thomas Altizer preserve the divinity of Jesus, arguing that through him God negates God's transcendence of being.

By denomination

Protestantism

In the Netherlands, 42% of the members of the Protestant Church in the Netherlands (PKN) are nontheists.[6] Non-belief among clergymen is not always perceived as a problem. Some follow the tradition of "Christian non-realism", most famously expounded in the United Kingdom by Don Cupitt in the 1980s, which holds that God is a symbol or metaphor and that religious language is not matched by a transcendent reality. According to an investigation of 860 pastors in seven Dutch Protestant denominations, 1 in 6 clergy are either agnostic or atheist. In one of those denominations, the Remonstrant Brotherhood, the number of doubters was 42 percent.[7][8] A minister of the PKN, Klaas Hendrikse has described God as "a word for experience, or human experience" and said that Jesus may have never existed. Hendrikse gained attention with his book published in November 2007 in which he said that it was not necessary to believe in God's existence in order to believe in God. The Dutch title of the book translates as Believing in a God Who Does Not Exist: Manifesto of An Atheist Pastor. Hendrikse writes in the book that "God is for me not a being but a word for what can happen between people. Someone says to you, for example, 'I will not abandon you', and then makes those words come true. It would be perfectly alright to call that [relationship] God". A General Synod found Hendrikse's views were widely shared among both clergy and church members. The February 3, 2010 decision to allow Hendrikse to continue working as a pastor followed the advice of a regional supervisory panel that the statements by Hendrikse "are not of sufficient weight to damage the foundations of the Church. The ideas of Hendrikse are theologically not new, and are in keeping with the liberal tradition that is an integral part of our church", the special panel concluded.[7]

A Harris Interactive survey from 2003 found that 90% of self-identified Protestants in the United States believe in God and about 4% of American Protestants believe there is no God.[9]

Catholicism

Catholic atheism is a belief in which the culture, traditions, rituals and norms of Catholicism are accepted, but the existence of God is rejected. It is illustrated in Miguel de Unamuno's novel San Manuel Bueno, Mártir (1930). According to research in 2007, only 27% of Catholics in the Netherlands considered themselves theist while 55% were ietsist or agnostic deist and 17% were agnostic or atheist. Many Dutch people still affiliate with the term "Catholic" and use it within certain traditions as a basis of their cultural identity, rather than as a religious identity. The vast majority of the Catholic population in the Netherlands is now largely irreligious in practice.[6]

Criticisms

In his book Mere Christianity, the apologist C. S. Lewis objected to Hamilton's version of Christian atheism and the claim that Jesus was merely a moral guide:

I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: 'I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God.' That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic—on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg—or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronising nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to. [...] Now it seems to me obvious that He was neither a lunatic nor a fiend: and consequently, however strange or terrifying or unlikely it may seem, I have to accept the view that He was and is God.

Lewis's argument, now known as Lewis's trilemma, has been criticized for, among other things, constituting a false trilemma. Philosopher John Beversluis argues that Lewis "deprives his readers of numerous alternate interpretations of Jesus that carry with them no such odious implications".[10]

Notable people

- William Montgomery Brown (1855–1937): American Episcopal bishop, communist author and atheist activist. He described himself as "Christian Atheist".[11]

- Douglas Murray (1979): British author, journalist and political commentator. He is a former Anglican who believes Christianity to be an important influence on British and European culture.[12][13][14][15]

- Anton Rubinstein (1829–1894): Russian pianist, composer and conductor. Although he was raised as a Christian, Rubinstein later became a Christian atheist.[16]

- Dan Savage (1964): American author, media pundit, journalist and activist for the LGBT community. While he has stated that he is now an atheist,[17] he has said that he still identifies as "culturally Catholic".[18]

- Gretta Vosper (1958): United Church of Canada minister who is an atheist.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ Ogletree, Thomas. "professor at Yale University". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Ogletree, Thomas W. The Death of God Controversy. New York: Abingdon Press, 1966.

- 1 2 Lyas, Colin. "On the Coherence of Christian Atheism." The Journal of the Royal Institute of Philosophy 45(171): 1970.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Altizer, Thomas J. J. The Gospel of Christian Atheism. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1966.

- 1 2 3 4 Altizer, Thomas J. J. and William Hamilton. Radical Theology and The Death of God. New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.,1966.

- 1 2 God in Nederland' (1996–2006), by Ronald Meester, G. Dekker, ISBN 9789025957407

- 1 2 Pigott, Robert (5 August 2011). "Dutch rethink Christianity for a doubtful world". BBC News. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ↑ "Does Your Pastor Believe in God?". albertmohler.com.

- ↑ Humphrey Taylor (October 15, 2003). "While Most Americans Believe in God, Only 36% Attend a Religious Service Once a Month or More Often" (PDF). The Harris Poll #59. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 6, 2010.

- ↑ John Beversluis, C.S. Lewis and the Search for Rational Religion (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985), p 56.

- ↑ "U.S. Heresy Trial. A "Christian Atheist."". The Times (43667). 2 June 1924. p. 13. col C.

- ↑ "Studying Islam has made me an atheist". December 29, 2008.

- ↑ "This House Believes Religion Has No Place In The 21st Century". The Cambridge Union Society. 31 January 2013.

- ↑ "On the Maintenance of Civilization". November 22, 2015.

- ↑ Holloway, Richard (7 May 2017). "Sunday Morning With..." BBC Radio Scotland. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017.

- ↑ Taylor, 280.

- ↑ "If Osama bin Laden were in charge, he would slit my throat; my God, I'm an atheist, a hedonist, and a faggot." Skipping Towards Gomorrah: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Pursuit of Happiness in America Dan Savage, Plume, 2002, p. 258.

- ↑ Anderson-Minshall, Diane (September 13, 2005). "Interview with Dan Savage". AfterElton.com.

- ↑ Andrew-Gee, Eric (16 March 2015). "Atheist minister praises the glory of good at Scarborough church". Toronto Star.

Vosper herself is a bit heterodox on the question of Christ. Asked if she believes that Jesus was the son of God, she said, ‘I don’t think Jesus was.’ That is, she doesn’t think He existed at all.

Further reading

- Soury, M. Joles (1910). Un athée catholique. E. Vitte. ASIN B001BQPY7G.

- Altizer, Thomas J. J. (2002). The New Gospel of Christian Atheism. The Davies Group. ISBN 1-888570-65-2.

- Hamilton, William, A Quest for the Post-Historical Jesus, (London, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 1994). ISBN 978-0-8264-0641-5.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Christian atheism |