Chris Rea

| Chris Rea | |

|---|---|

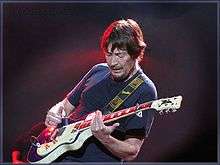

Chris Rea performing in Congress Hall, February 2012 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Christopher Anton Rea |

| Born |

4 March 1951 Middlesbrough, North Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1978–present |

| Labels | |

| Website |

chrisrea |

Christopher Anton Rea (/ˈriːə/ REE-ə; born 4 March 1951)[1] is a British rock and blues singer-songwriter and guitarist, recognisable for his distinctive, husky-gravel voice and slide guitar playing.[2][3] The book Guinness Rockopedia described him as a "gravel-voiced guitar stalwart".[4] The British Hit Singles & Albums stated that Rea was "one of the most popular UK singer-songwriters of the late 1980s. He was already a major European star by the time he finally cracked the UK Top 10 with his 18th chart entry; "The Road to Hell (Part 2)".[5] Two of his studio albums, The Road to Hell and Auberge, topped the UK Albums Chart.[5] Rea was nominated three times for the Brit Award for Best British Male Artist: in 1988, 1989 and 1990.[6][7][8] As of 2009, he has sold more than 30 million albums worldwide.[9]

In America he is best known for the 1978 hit song "Fool (If You Think It's Over)" that reached No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 and spent three weeks at No. 1 on the Adult Contemporary chart. This success earned him a Grammy nomination as Best New Artist in 1979.[10] His other hit songs include, "I Can Hear Your Heartbeat", "Stainsby Girls", "Josephine", "On the Beach" (Adult Contemporary No. 9), "Let's Dance", "Driving Home for Christmas", "Working on It" (Mainstream Rock No. 1), "Tell Me There's a Heaven", "Auberge", "Looking for the Summer", "Winter Song", "Nothing To Fear", "Julia", and "If You Were Me", a duet with Elton John.[11]

Biography

Early life

Christopher Rea was born in Middlesbrough in the North Riding of Yorkshire in a Roman Catholic family[12] to an Italian father, Camillo Rea (died December 2010),[13] and an Irish mother, Winifred Slee (died September 1983),[14] as one of seven children.[15] The name Rea was well known locally thanks to Camillo's ice cream factory and café chain.[4][13][16] During his childhood Rea went almost every summer for a few months to Italy, and at the age of 12 started to work as a table clearer in the coffee bar, and soon in making the ice-cream in the factory. Initially he was interested to learn about and improve the business, but his ideas did not get support from his father, and he eventually left and was replaced by one of his brothers.[17]

1970s–82: Early career and "Fool (If You Think It's Over)"

It was at the comparatively late age of 21–22 that Rea bought his first guitar,[15][18] a 1961 Hofner V3 and 25-watt Laney,[19] after he left school.[20] With regard to his guitar playing technique, "bottleneck" also known as slide guitar, and music style, Rea developed it with inspiration of Charlie Patton (who he heard on the radio and initially erroneously thought his playing sounded like a violin),[18][21][19] but also Blind Willie Johnson and Sister Rosetta Tharpe,[21] as well by the success of then contemporary Ry Cooder and Joe Walsh.[18][22] He was also listening to Delta blues musicians like Sonny Boy Williamson II and Muddy Waters,[23] especially gospel blues,[19] and opera to light orchestral classics to develop his style.[14] He recalls that "for many people from working-class backgrounds, rock wasn't a chosen thing, it was the only thing, the only avenue of creativity available for them",[23] and that "when I was young I wanted most of all to be a writer of films and film music. But Middlesbrough in 1968 wasn't the place to be if you wanted to do movie scores".[23] Due to his late introduction to music and guitar playing compared to Mark Knopfler and Eric Clapton, Rea commented how "I definitely missed the boat, I think".[18] He was self-taught,[20] and soon tried to join a friend's group, The Elastic Band, as the first choice for guitar or bass, but according to his father's advice he did not start because the payment was not enough to pay the costs. He found himself working casual labouring jobs, including working in his father's ice cream business.[24] Rea commented that at that time he was "meant to be developing my father's ice-cream cafe into a global concern, but I spent all my time in the stockroom playing slide guitar".[21]

In 1973 he joined the local Middlesbrough band Magdalene, which different line-up featured David Coverdale who went on to join Deep Purple.[4][15][20][25] He began by writing the band's songs, and only took up singing because the singer in the band did not show up.[15] Rea then went on to form the band The Beautiful Losers with which in 1975 he received the Melody Maker Best Newcomers award, but as he secured a solo recording deal with independent Magnet Records,[22] and released his first single entitled "So Much Love" in 1974,[26] the band split in 1977.[24][27] In 1977 he performed on Hank Marvin's album The Hank Marvin Guitar Syndicate and also guested on Catherine Howe's EP The Truth of the Matter.[1] In the same year was recorded his first album, but according to Michael Levy (co-founder of Magnet) it was started all over again because it did not capture his whole talent.[28]

In 1978, Whatever Happened to Benny Santini? was Rea's debut studio album. It was released in June and was produced by Elton John's record producer Gus Dudgeon.[29] The title of the album was a reference to "Benjamin Santini", the stage name that Rea sarcastically invented but the record label insisted that he should adopt.[1][23] The album peaked at No. 49 on the Billboard Hot 200, and charted for 12 weeks.[30] The first single taken from the album, "Fool (If You Think It's Over)", was Rea's biggest hit in the US, peaking at No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 and reaching No. 1 on the Adult Contemporary Singles chart.[31][32] Like most of Rea's early singles, "Fool (If You Think It's Over)" failed to appear on the UK Singles Chart on its first release and only reached No. 30 when was re-released in late 1978 to capitalise on its U.S. achievement.[5] The overall success was Magnet Records' major breakthrough and their first Top-10 success in the U.S., making Rea their biggest artist. Levy remembers him as "more of a thoughtful, introspective poet than a natural pop performer" which stopped him from becoming not only a major star, but a megastar.[28] However, as the record label had the idea of him being a mix of piano-playing singer-songwriters Elton John and Billy Joel,[23] it gave the record buyers a different impression of him than what he felt was correct for three or four years.[18] Rea noted that the hit song "is still the only song I've ever not played guitar on, but it just so happened to be my first single, and it just so happened to be a massive hit",[18] and that he "always had a difficult relationship with fame, even before my first illness. None of my heroes were rock stars. I arrived in Hollywood for the Grammy Awards once and thought I was going to bump into people who mattered, like Ry Cooder or Randy Newman. But I was surrounded by pop stars".[33][34]

Dudgeon went on to produce Rea's next studio album Deltics (1979), then Rea was able to record the third Tennis (1980) with members from Middlesbrough, which received positive reviews.[24] He soon became married, and as both albums failed commercially the record company refused even his artwork cover for the fourth album Chris Rea (1982), which was untitled.[24] The albums did not manage to enter Top 50 in the UK, and failed to provide further hit singles, as "Diamonds" reached No. 44 and "Loving You" No. 88 on the Billboard Hot 100.[35][36] Rea has since spoken about the difficult working relationship he had at the time with Dudgeon and other "man in suits" who he felt 'smoothed out' the blues-influenced elements of his music.[23][37][24] He recalls that "always thought that they [producers] knew best. I never thought for a minute that they might have another agenda", and "all of a sudden [since 1978] I was the goose that laid the golden egg, and it was hell for me",[21] however that "can't blame anyone but myself. I gave them what they wanted rather than what I wanted".[38]

1983–2000: European breakthrough and success, The Road to Hell and Auberge

Since 1983s his music began to sound according to his wishes and capabilities, mostly because he was in such a situation of companies pressure due to the accumulated costs of the production of the previous four albums that they accepted his demo tapes of fifth studio album Water Sign. After finding out that Dudgeon made more money than he did, changed a manager and went on a UK club tour, and then to a 60-date tour as a support act for Canadian band Saga.[24] Suddenly, even on his company surprise,[24] the album became a hit in Ireland and Europe, selling over half a million in just a few months and the single "I Can Hear Your Heartbeat" taken from it entered the top 20 across Europe.[26] With the album's success and following Wired to the Moon (1984), which was his first Top 40 in the UK (#35[39]), Rea began to focus his attention on touring continental Europe and built up a significant fan base. He particularly became popular in Germany, and believes this audience saved his career as there was no "image-led market", but only "by music and by word of mouth".[24] It was not until 1985's million-selling Shamrock Diaries and the songs "Stainsby Girls" (a tribute to the girls – including his wife – that he knew from Stainsby secondary modern school near Middlesbrough[40]) and "Josephine" (a tribute to his daughter) that UK audiences began to take notice of him.[24]

His following albums were also million-selling On The Beach (1986), and Dancing with Strangers (1987), including his first Top 20 UK single "Let's Dance" (No. 12[39]),[4] with the latter album reaching No. 2 on the UK albums chart, being behind Michael Jackson's Bad.[24] It was not until 1987 that he could pay off the amassed £320,000 debt to the record company, and start to receive significant revenue.[41] In 1986 he was a support act along The Bangles and The Fountainhead for Queen at Slane Concert for an estimated 80,000 audience,[42] and The Dancing with Strangers tour in 1987 saw Rea sell out stadium size venues for the first time across the world, including Wembley Arena twice,[24] as well as having concerts in Japan.[28] In early 1988 for the first time he was in Australia, while in America signed with Tamla Motown, however, being told that I 'should stay and tour there for three years', on behalf of his family he did not accept it. He commented that at the time he realized that "I could be as big as I liked, if I was prepared to do the touring".[24]

His following album was his first compilation, New Light Through Old Windows (1988), which reached No. 5 in UK,[39] was another million seller and included re-workings of his then hit singles.[4] Some of them were successful in the US, as new song "Working On It" reached No. 73 on Billboard Hot 100 and topped the Mainstream Rock chart,[43][44] while the re-recorded version "On the Beach (1988)" reached Top 10 on the Adult Contemporary chart,[45] also No. 12 in UK.[39] It was followed by an international tour with over 45 dates.[24]

His next studio album was Rea's major breakthrough.[4] The Road to Hell (1989) enjoyed massive success and became his first No. 1 album in the UK, being certified 6× Platinum by BPI until 2004.[46] This accomplishment could not be mirrored in the US where it only reached No. 107[47] in spite of the single track "Texas" achieving extensive radio airplay, and single "The Road to Hell (Part 2)" peaking at No. 11 on Mainstream Rock chart.[48] The title track was Rea's first and only UK Top 10 single.[39] Rea appeared and performed on the Band Aid II project's single "Do They Know It's Christmas?" in December 1989.[4] His next album Auberge (1991) was also a No. 1 UK and European hit album, including the single of the same title which reached Top 20 in UK.[39]

After Auberge, Rea released God's Great Banana Skin (1992) which reached No. 4 in the UK,[4] while the single "Nothing to Fear" gave him another Top 20 hit.[39] A year later album Espresso Logic hit the Top 10 and "Julia", written about his second daughter, gave him sixth and last Top 20 single position.[39] The album was partly promoted by Rea taking part in the British Touring Car Championship, although he was eliminated in the first round.[4] In 1994 was released another million-selling compilation The Best of Chris Rea, which peaked at No. 3 in UK,[39] and in 1996 released soundtrack La Passione. In 1998 released fourteenth studio album The Blue Cafe, and it made to the UK Top 10. In 1999, 10 years after Road to Hell, Rea released electronica album The Road to Hell: Part 2, which never made the UK Top 40. In 2000, he released King of the Beach, which hit the UK Top 30.[39]

2001–05: Illness and return to the roots of Blues music

Rea has had peritonitis and stomach complications since 1994, as well as several operations.[33][49] In 2000 Rea was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and somewhere in between 2000–2001 Rea underwent a Whipple procedure,[21][38][50][51] by which he lost the head of the pancreas and part of duodenum, bile duct, and gall bladder.[20][33] Since having his pancreas removed, Rea has had problems with diabetes and a generally weaker immune system and has to take thirty-four pills and seven injections a day.[52] He has since undergone several serious operations.[20][33] Nevertheless, he found even greater appreciation for life, his family, and the things he loves.[20][33][53]

In an interview, Rea revealed that "it's not until you become seriously ill and you nearly die and you're at home for six months, that you suddenly stop, to realise that this isn't the way I intended it to be in the beginning. Everything that you've done falls away and start wondering why you went through all that rock business stuff".[20] Although the record company offered him millions to do a duets album with music stars,[14] having promised himself that if he recovered he would be returning to his blues roots,[21] he set up his own independent Jazzee Blue label to free himself from the pressure of record company expectations, and recorded Dancing Down the Stony Road (2002), which reached No. 14[39] and was certified Gold by BPI.[14][20][21] He also wanted for the label to be a place "where musicians came and made a record" for this kind of music, releasing several blues and jazz instrumental albums mostly fronted by his band members,[54] such as produced by him blues-jazz record Guitars Unlimited (2003) with an eight-piece guitar orchestra (with Sacha Distel[55]), but was disappointed with the music business and radio broadcasting when Michael Parkinson (who initially supported him to do the record) told him the songs which are longer than three minutes are not allowed to be played anymore.[41]

He has since released two instrumental studio blues albums Blue Street (Five Guitars) and Hofner Blue Notes in 2003, critically acclaimed The Blue Jukebox (2004),[20] and in 2005 he released Blue Guitars, an album which included 11 CDs with 137 blues-inspired tracks, with his own paintings as album covers.[34] Rea concluded: "I was never a rock star or pop star and all the illness has been my chance to do what I'd always wanted to do with music [...] the best change for my music has been concentrating on stuff which really interests me".[34]

2006–present: Continuation of Blues albums and tours

In February 2008, Chris Rea released a new album, The Return of the Fabulous Hofner Blue Notes (a dedication to the 1960s Hofner guitar), featuring 38 new tracks on three CDs and two vinyl, which included a hardback book of his paintings.[20] In writing the album, Rea dreamed up a band that had never existed – a pastiche instrumental group from the late 1950s called The Delmonts, who in early 1960s evolved into blues band The Hofner Bluenotes.[56] The release of the album was followed by a European tour, in which he was part of both fictional bands playing their musical repertoire,[57] visiting various venues across the UK, including the Royal Albert Hall in London.[58]

In October 2009, Rea released a new 2-disc best of compilation Still So Far to Go which contained some of his best known (and lesser known) hits over the last thirty years, as well as more recent songs from his "blues" period.[34] Two new songs were included, "Come So Far, Yet Still So Far to Go" and the ballad "Valentino".[34] The album was a success as it reached No. 8[39] and was certified Gold by BPI. In January 2010 Rea started the European tour, called "Still So Far to Go".[34] His special guest on stage was Irish musician Paul Casey. The tour ended on 5 April at Waterfront Hall in Belfast.[34]

In September 2011, Chris Rea released Santo Spirito Blues, which contained two feature-length films on DVD written and directed by him, and two accompanying CDs of the soundtracks, and one regular CD of studio album songs.[59] In October and November, he underwent two surgical procedures.[60] On 3 February 2012 the Santo Spirito Tour started at Congress Center Hamburg in Hamburg, Germany, with additional visits to Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Hungary, Switzerland, Netherlands, Belgium and France. The United Kingdom part of the tour commenced in the middle of March and finished on 5 April at Hammersmith Apollo in London.[59]

In November 2014, Rea embarked on a European tour called The Last Open Road Tour, while the UK part of the tour commenced on 1 December in Manchester and ended on 20 December in London.[61][62] He also performed at the 2014 Montreux Jazz Festival.[63][64] In November 2015, Rea released a re-recording of his 1996 soundtrack La Passione in a deluxe package which consists of two CDs and two DVDs enclosed within a 72-page book.[19][65]

In 2016, Rea suffered a stroke, which left him with slurred speech and reduced movement in his arms and fingers. Soon afterwards he quit smoking to deter further strokes, and gradually recovered well enough to record and tour.[66] In September 2017, Chris Rea released his twenty-fourth album, Road Songs for Lovers, and embarked on a new European tour starting in October until December.[67][68] On 9 December, Rea collapsed during a performance at the New Theatre Oxford, the 35th concert of the tour.[69] He was taken to hospital, with his condition stabilised,[70] and the last two concerts cancelled.[71]

Guitars

Rea's first guitar was Höfner Verithin 3, which he bought in a second-hand shop because at the time there was not a great guitar choice in Middlesbrough.[21] He played V3 until 1979, and although it was a "dreadful guitar with an appalling action, but playing slide it didn't matter".[72] During his career, the most recognisable guitar was 1962 Fender Stratocaster called "Pinky", which he bought after a Ry Cooder concert at the City Hall in Newcastle. The guitar once was submerged in water for three months and was more mellow in sound compared to the classic hard Stratocaster sound. Since 2002 Dancing Down the Stony Road, his main guitar was Italia Maranello called "Bluey".[19][72]

Personal life

Family life

Rea is married to Joan Lesley, with whom he has been in a relationship since they met as teenagers on 6 April 1968 in their native Middlesbrough.[24][34] They have two daughters, Josephine, born 16 September 1983, and Julia Christina, born 18 March 1989.[18] Josephine lectures on Renaissance art in Florence and Julia is at University of St Andrews.[53] Rea used to live at Cookham, Berkshire, where he owned Sol Mill Recording Studios and produced some of his later albums.[20][21]

Other interests

Rea is a fan of historic motor racing and races a Ferrari Dino,[52] a Ferrari 328,[73] and a 1955 Lotus 6,[73][74][75] and managed to race at Monza circuit.[76] He owned and raced the 1964 Lotus Elan 26R,[73][77][78] and the well known Caterham 7 from the Auberge album cover,[79] until it was sold in 2005 with all proceeds (£11,762) going to the charity NSPCC.[80] He also owned Ferrari 330 which was used as a donor car for the replica of Ferrari 250 Le Mans used in the 1996 movie La Passione.[81] In 2014, he was completing a 22-year restoration of an original replica of Ferrari 156.[18] He also joined Historic Racing Drivers Club, where he drives a Morris 1000 1957 police car.[66]

He has taken the opportunity to get involved in Formula One on a few occasions, including as a pit lane mechanic for the Jordan team during the 1995 Monaco Grand Prix.[82] He recorded a song, "Saudade", in tribute to three-time Formula One world champion Ayrton Senna. It featured prominently in the BBC documentary movie.[83]

When he is not writing songs, other interests include gardening and particularly painting.[76] Rea says that he likes to "read a lot and even though I chose music, journalism was my first passion. I wanted to be a journalist and write about car racing [...] somewhere deep down I believe I could have been a decent journalist".[60]

Politics

In August 2008, it was erroneously reported that Rea had donated £25,000 to the Conservative Party.[84] This was followed by further claims in 2009 by The Times that Rea has been a longtime supporter of the Conservative Party,[85] and incorrect reports in April 2010, just weeks before the UK general election, that Rea had donated a further £100,000 to the Conservatives.[86] The donations were in fact made by a businessman called Chris Rea and not the musician.[87] This error has been acknowledged by The Daily Mail newspaper, which printed a retraction.[88]

In an interview in 2012, Chris Rea denied those claims and noted that this was a classic example of how dangerous the internet can be, while criticising the politicians and government of the UK and EU as remote from the common people.[60] He is sceptical about the idea of unification of Europe because with a common European market "you cannot force different people to live together [when] they simply do not want to",[60] recalling the downfall of Yugoslavia.[60]

Filmography

One of his childhood dreams was to become a film writer and film music composer.[15][23] Rea wrote the title track and music score for the 1993 drama film Soft Top Hard Shoulder,[89][90] 1996 film La Passione, and had a cameo role in it.[4] Rea was the lead actor in the 1999 comedy film Parting Shots, alongside Felicity Kendal, John Cleese, Bob Hoskins and Joanna Lumley.[15] Rea, ironically, played a character who was told that cancer gave him six weeks to live and decided to kill those people who had badly affected his life.[4][15] Afterwards, two feature-length films were made for the Santo Spirito Blues project, just "so that I could do the music".[15]

References in lyrics

Rea has acknowledged that several of his songs were "born out of Middlesbrough", his hometown. The verse "I'm standing by a river, but the water doesn't flow / It boils with every poison you can think of" from "The Road to Hell",[20] the songs "Steel River" which refers to a nickname for River Tees,[91][92] and "Windy Town,[20] reflect Rea's feelings about the industrial decline of Middlesbrough and the re-development of the town centre while he was out of the country touring through the years:

"I went back to see my father after my mother had died and the fuckers had knocked the whole place down. I'd been gone three years, hard touring in Europe. I literally went to drive somewhere that wasn't there. It was like a sci-fi movie. The Middlesbrough I knew, it's as if there was a war there 10 years ago."[24][93]

"I miss the bits of Middlesbrough that aren't there any more. It's very hard to accept that Ayresome Park no longer exists. I know I sound very old when I say things like that. Those terraced streets are no longer there. But I miss the old character of the place, the guys with the fruit barrows and all that."[20]

Discography

Studio albums

- Whatever Happened to Benny Santini? (1978)

- Deltics (1979)

- Tennis (1980)

- Chris Rea (1982)

- Water Sign (1983)

- Wired to the Moon (1984)

- Shamrock Diaries (1985)

- On the Beach (1986)

- Dancing with Strangers (1987)

- The Road to Hell (1989)

- Auberge (1991)

- God's Great Banana Skin (1992)

- Espresso Logic (1993)

- La Passione (1996)

- The Blue Cafe (1998)

- The Road to Hell: Part 2 (1999)

- King of the Beach (2000)

- Dancing Down the Stony Road / Stony Road (2002)

- Blue Street (Five Guitars) (2003)

- Hofner Blue Notes (2003)

- The Blue Jukebox (2004)

- Blue Guitars (2005)

- The Return of the Fabulous Hofner Bluenotes (2008)

- Santo Spirito Blues (2011)

- Road Songs for Lovers (2017)

Compilation albums

- New Light Through Old Windows (1988)

- The Best of Chris Rea (1994)

- The Very Best of Chris Rea (2001)

- Heartbeats – Chris Rea's Greatest Hits (2005)

- Chris Rea: The Ultimate Collection 1978–2000 (2007)

- Still So Far to Go: The Best of Chris Rea (2009)

- The Journey 1978-2009 (2011)

References

- 1 2 3 Strong, Martin C. (2000). The Great Rock Discography (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Mojo Books. pp. 800–801. ISBN 1-84195-017-3.

- ↑ David Sinclair (27 April 2006). "Chris Rea". The Times. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

From being a multimillion-selling, soft-rock tunesmith, Rea, 55, has turned into a hardcore disciple of the electric blues.

- ↑ Danny Scott (3 December 2017). "Me and My Motor: singer Chris Rea". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Roberts, David (1998). Guinness Rockopedia (1st ed.). London: Guinness Publishing Ltd. pp. 354–355. ISBN 0-85112-072-5.

- 1 2 3 Roberts, David (2005). British Hit Singles & Albums. London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 60. ISBN 1-904994-00-8.

- ↑ "1988 Brit Awards". Awards & Winners. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "1989 Brit Awards". Awards & Winners. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "1990 Brit Awards". Awards & Winners. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "Programmes | 'Still so far to go'". BBC News. 5 October 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ "Bee Gees Head Lists For 6 Grammy Awards". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. The News-Journal Corporation. 9 January 1979. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Gregory, Andy, ed. (2002). The International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002. Psychology Press. p. 424. ISBN 978-1857431612.

- ↑ Matt Westcott (15 March 2012). "Chris Rea's long and winding road". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 Robson, Dave (10 December 2010). "Teesside ice cream legend Camillo Rea dies". Gazette Live. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Keith Shadwick (26 March 2004). "Chris Rea: Confessions of a blues survivor". The Independent. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Graham Young (5 November 2014). "Chris Rea says Birmingham NIA gig will be a 'holiday' from fighting pancreatic cancer". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Welford, Joanne (23 July 2017). "Behind the scenes at Rea's Creamy Ices". Gazette Live. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ Danny Danziger (29 November 1993). "The Worst of Times: Up to my elbows in ice-cream: Chris Rea talks to Danny Danziger". The Independent. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Singer Chris Rea: 'Coping with not having a pancreas can be pretty awful'". The Belfast Telegraph. 28 November 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 David Mead (15 June 2016). "Chris Rea on his guitar origins, Strats, the blues and La Passione". MusicRadar. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Middlesbrough superstar Chris Rea speaks exclusively about recovering from illness and his return to touring". ne4me. 5 March 2010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Will Hodgkinson (13 September 2002). "Chris Rea interview". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- 1 2 Auf Wiedersehen, Pet..., Q, February 1988, p.33

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 John Walsh (2 May 1997). "The reluctant rocker". The Independent. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Paul Du Noyer (February 1988). "Chris Rea: The Underdog's Tale". Q. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Lazell, Barry (1989). Rock movers & shakers. Billboard Publications, Inc. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-8230-7608-6.

1973 He becomes a proficient enough guitarist to join local professional band, Magdelene (whose singer David Coverdale has just left to join Deep Purple), and begins to develop his songwriting skills

- 1 2 Record Collector, December 1986, No.88, p.39

- ↑ Graham Young, Mieka Smiles (5 November 2014). "'I've had five operations but I just keep going and I'm very lucky for that': Chris Rea on his long fight against cancer". Gazette Live. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Levy, Michael (2008). A Question of Honour: Inside New Labour and the True Story of the Cash for Peerages Scandal. Simon and Schuster. p. 49–50, 69. ISBN 978-1-4165-9824-4.

- ↑ "Billboard's Top Album Picks: For Week Ending 7/22/78". Billboard. Vol. 90 no. 29. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 22 July 1978. p. 94. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "What Ever Happened To Benny Santini (Hot 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Fool If You Think It's Over (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Fool If You Think It's Over (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Garth Pearce (29 September 2009). "If cancer hadn't nearly killed me, I'd be just another selfish celebrity egomaniac, says Chris Rea". Daily Mail. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Chris Rea, past, present and future". Saga. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ "Diamonds (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Loving You (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Auf Wiedersehen", Pet..., Q magazine, February 1988, pp.33-4

- 1 2 Rebecca Fletcher (28 September 2002). "Interview: Chris Rea – My Road To Hell; How a Near-Death Experience Made Singer Chris Rea Realise What He Really Wanted out of Life". The Mirror. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Official Charts > Chris Rea". The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ↑ http://www.jonkutner.com/stainsby-girls/

- 1 2 Henry Yates (1 December 2015). "An Interview With The Straight-Talking, No-F**ks-Given Chris Rea". TeamRock. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ Joe O’Brien (7 July 1986). "Queen Take to the Stage in Slane 1986". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ "Fool If You Think It's Over (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Working On It (Mainstream Rock)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "On The Beach (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Chris Rea - The Road To Hell". BPI. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "Road To Hell (Hot 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "The Road To Hell (Mainstream Rock)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Rock: torna Chris Rea Un tour anche in Italia". Corriere della Sera (in Italian): 24. 2 February 1998. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Chris Rea operato d' urgenza: tolto il pancreas". Corriere della Sera (in Italian): 34. 4 August 2000. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Chris Rea plays North East gigs". BBC News. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- 1 2 Gavin Martin (2 October 2009). "Chris Rea's fighting fit and raring to go". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- 1 2 Garth Pearce (17 September 2015). "Chris Rea on cancer, family, fame and the key to happiness". Saga. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Mark Edwards (27 July 2003). "Chris Rea: Blue Street". The Times. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "Various - Guitars Unlimited". Discogs. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "Chris Rea – Return of the Fabulous Hofner Bluenotes". Amazon. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "Review: Chris Rea, Newcastle City Hall". The Journal. 3 April 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "Win! Tickets To See Chris Rea!". Uncut. 27 February 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Chris Rea announces Santo Spirito tour". Music-News. 7 February 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Chris Rea: There's no escape from the road to". Kyiv Weekly. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ↑ "Chris Rea Announces December 2014 UK tour". gigwise.com. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ Andrew Johnston (8 December 2014). "Chris Rea review: Guitar hero hasn't run out of fuel". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ "Chris Rea distille le blues d'un survivant qui sent fort le bourbon". 24 heures (in French). 6 July 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ "Interviews – Chris Rea". Montreux Jazz Festival. 5 July 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ "Chris Rea – La Passione". discogs. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Chris Rea on his fight with pancreatic cancer: I'm never going to be what I used to be". Daily Express. 24 September 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Dave Robson (24 April 2017). "Chris Rea reveals tour dates as he goes back on the road again". Gazette Live. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Dave Lawrence (22 November 2017). "Review: Chris Rea, Sage Gateshead". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Lin Jenkins (9 December 2017). "Chris Rea 'stable' after on-stage collapse at Oxford theatre". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Nicola Harley (10 December 2017). "Chris Rea, Driving Home For Christmas star, 'stable' after 'falling into a clump' on stage". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ Laura Harding (11 December 2017). "Chris Rea cancels another show after collapsing on stage". The Independent. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- 1 2 "How I got started... Chris Rea". The Guitar Magazine. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Rob Widdows (September 2009). "The Racing Bluesman". Motor Sport. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ "The aim is to beat Chris Rea". Stirling Moss. 25 July 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ "Chris Rea". Forums.atlasf1.com. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- 1 2 Paula Kerr (20 April 2012). "My haven: The musician and aspiring painter, Chris Rea, 61, draws inspiration from the garden of his Berkshire home". Daily Mail. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ "Historic Race Meeting – Donington Park" (PDF). Historic Sports Car Club (HSCC). 5 April 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ "1964 Lotus 26R". Jan B. Lühn. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ Martin Buckley (11 December 2009). "Graham Nearn: Engineer and businessman behind the Caterham Seven sports car". The Independent. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ "Lot 229: 1987 Caterham 7 Sprint 'Blue Seven'". Motorbase.com. Taer limited. 29 September 2005. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ Don Standhaft. "Ferrari 250 TRI61 Le Mans". DMark Concepts. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Warwick, Matt (29 May 2016). "Monaco GP: 'I saw Senna's glove – he'd worn through it'". BBC Sport. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ "the career and life of Senna". BBC News. 1 May 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ Kirkup, James (28 August 2008). "Chris Rea among high-profile donors to Conservative Party". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Baldwin, Tom; Sherwin, Adam; Simpson, Eva (14 November 2009). "Not the X Factor – more the Why Factor as celebrities snub parties". The Times. London.

- ↑ "Tories raise twice the amount of big donations given to Labour in first week of campaign". The Guardian. London. 20 April 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ "The seal of success: Chris Rea". agendaNI. 10 March 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ Doughty, Steve (21 April 2010). "Tories bank £1.45million in donations in first week of election campaign – twice that of Labour". Daily Mail. London.

- ↑ "Soft Top, Hard Shoulder – double BAFTA-winning comedy starring Peter Capaldi". Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ↑ Jim White (28 January 1993). "Hello? Is anybody out there?: Chris Rea: Wembley Arena". The Independent. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ "Middlesbrough History". Englandsnortheast.co.uk. 17 October 1911. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ "Chris Rea plays North East gigs". BBC News. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Auf Wiedersehen, Pet..., Q, February 1988, p.34

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Chris Rea |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chris Rea. |