Chinese spirit possession

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

|

Internal traditions Major cultural forms

Main philosophical traditions: Ritual traditions: Devotional traditions: Confucian churches and sects: |

| Chinese folk religion's portal |

Chinese spirit possession is a practice performed by specialists called jitong (a type of shamans) in Chinese folk religion, involving the "channelling" of Chinese deities who take control of the specialist's body, resulting in noticeable changes in body functions and behaviour. The most famous Chinese spirit possession practitioners took part in the Boxer Rebellion in the 1900s, when boxers claimed to be invulnerable to the cut of a sharp knife, gunshots, and even cannon fire.

History

The State of Qi had shamans who claimed to be possessed by gods, and they were criticized as heterodox by Confucians. Movements led by shamans practicing spiritual possession often led peasant rebellions against the ruling dynasty during Chinese history. The Boxer Rebellion was one of many peasant movements that had shamans who claimed to be possessed by spirits.[1] For the Boxers during the Boxer Rebellion, spirit possession was used for protective purposes.[2]

Accounts

Larry Clinton Thompson, in his book "William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris and the ”Ideal Missionary”, has a description of the spirit possession practiced by Chinese boxers:

... whirling and twirling of swords, violent prostrations, and chanting incantations to Taoist and Buddhist spirits. When the spirit possession had been achieved, the boxers would obtain invulnerability and superhuman skills with swords and lance.

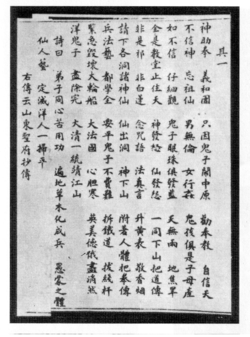

Incantations

- (1) Incantation to invite the coming of spirits.

- (2) Incantation to provide protection against spear and fire.

- (3) Incantation to provide protection against any outside attack.

Spiritual possession practitioners during the Boxer Rebellion and 20th century warfare claimed that once these incantations were chanted, Chinese deities would descend to offer protection, so that cannon fire or gunshots would not harm the human body.[4]

Claimed abilities

- (1) Thunder bolts in the palm (Chinese:五雷掌).

- (2) Climbing ladder made of sharp knives (Chinese:上刀山)

- (3) Invulnerable to gunshots, cannon fire, and knife attack.

- (4) Ability to command divine spirit warriors.

See also

References

- ↑ Joseph Esherick (1988). The origins of the Boxer Uprising. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-520-06459-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Paul A. Cohen (2003). China unbound: evolving perspectives on the Chinese past. Psychology Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-415-29823-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Thompson, Larry Clinton. William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: heroism, hubris and the " Ideal Missionary". McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-4008-5.

- ↑ 侯宜傑 (2010-10-08). 「神拳」義和團的真面目. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司. p. 151. ISBN 978-986-221-531-9.