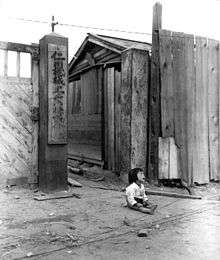

Childhood in war

Childhood in war refers to children who have been affected, impaired or even injured during and in the aftermath of armed conflicts. Wars affect all areas of involved persons' life, including physical and mental-emotional integrity, social relations with the family and the community, as well as housing. More often than not, these experiences affect a child's further development.

The Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research estimated that there were 226 politically-motivated armed conflicts (of which 38 estimated as highly violent: 18 full-scale wars, 20 limited wars) worldwide during 2016.[1] According to a Spiegel TV documentary in early 2016, estimated 230 million children live in war and crisis areas, experiencing everyday terror.[2]

War child

Children are generally not the first to come to mind when victims of war and the aftermath of war are considered. They remain hidden behind the focus on political and material outcomes of war, even when war-induced injuries or disabilities become visible. The term war child takes on almost immeasurable significance when it is used consistently world-wide for all children of war across time.

In Germany, the concept of war child developed in the beginning of the 1990s when the generation that had experienced the Second World War during their childhood began to break their silence.[3] Since then the concept of war child has received broad media attention, especially in Germany. At the same time, science and research have examined the phenomenon of the childhood of these war children.[4]

Internationally, the concept of war child can take on interpretations that are different in other languages and can be associated with very different meanings. Differences, for example, become apparent when it relates to the war children in occupied Poland during the Second World War.[5] The English term war child[6] as well as the French term enfant de la guerre are used in some countries as a synonym for children who have one native parent and one parent from a member of an occupying military force.[7] While that definition of war child is different from the definition in this article, they both refer to the Second World War. In France alone, the number of children of German occupying soldiers from the Second World War is estimated to be 200,000.[8] Although these are children who grew up during war, they are usually associated with the deprivation and humiliation that is part of their origin which they, as well as their mothers, have experienced.[7] While these experiences may lead to considerable impairment of identity and self-esteem, some of these children perceive the option of dual nationality as liberating.[9][10]

Additional aspects arise when considering children of war outside of the European region or those of the 21st century. Conflicts like the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945, the Vietnam War between 1955 and 1975, the 1971 Bangladesh genocide during the Bangladesh Liberation War, or the Syrian Civil War since 2011, all brought specific implications for the children of these wars. In Japan, the war children of that time still suffer from radiation-induced mutations. Regarding the Vietnam War, different consequences arose, depending on whether Napalm or the defoliant Agent Orange was used. The long-term effect on the war children in Syria, in Afghanistan or in Eastern Ukraine since 2014 are not yet foreseeable – with the exception of the numerous mutilations caused by land mines.[11]

Occasionally the public becomes aware of symptoms that have been observed in refugee children from war zones. In April 2017, for example, unusual reactions were reported in Sweden: "Children fall into permanent unconsciousness when their families are threatened with deportation."[12] Swedish physicians have been dealing with this phenomenon "for years" without being able to explain why there are no similar cases in other countries.

With respect to military use of children,[13] of whom there are an estimated 250,000 around the world, additional issues come into focus. Events like the International Day Against the Use of Child Soldiers cannot help against the fact that every year "tens of thousands of children and young people are recruited as soldiers"[14] – "some of them are only eight years old".[15] On September 2nd, 1990, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child came into effect which is intended to provide protection to children, including during times of war. It has been ratified by almost all member states and some non-member states. In 2002, an additional protocol came into force which ostracized the use of minors as child soldiers in armed conflicts. However, many states do not adhere to it. In Germany as well, minors are recruited for military service.[16]

Individual war children who gain attention in the media and thereby bring the issue of war children into public view, represent exceptional cases. Those include Malala Yousafzai from Pakistan or Phan Thị Kim Phúc from Vietnam. Malala received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014, jointly with her father. While Kim Phúc survived the use of Napalm in the Vietnam War in June 1972, she suffered severe burns. A photo of press photographer Nick Út made her known all over the world.[17]

Documentation

"No one wants to see children in war", states UNICEF.[18] Yet, they are constantly at risk of being used for various, at times untrustworthy, purposes, and they are almost daily in the news. In the arts, however, they are seldom visible, even in times when painters, for example, created countless works dealing with war.[19] There are isolated exceptions – in music,[20] fine arts,[21] and literature.[22] The documentary treatment of the subject is different. Numerous documentary films and reports have emerged which bear witness to past and present wars and the children affected by them. Furthermore, many of the projects on this topic are based on materials by contemporary witnesses.

Documentary films and reports (in German)

Contemporary witness projects

The Protestant Adult Education center in Thuringia, Germany (Evangelische Erwachsenenbildung Thüringen) created a contemporary witness project in which war children have also found recognition. As part of the project, a traveling exhibition by historian Iris Helbing shows drawings by Polish war children from 1946.[23] The drawings originated from a drawing contest for children 13 years and younger. The contest was arranged by the magazine Przekrój one year after its founding in 1945 and on the occasion of the anniversary of the liberation of Poland:

At that time, the drawings were regarded as important material in the investigation and documentation of crimes against Polish children by the National Socialists. The greatest number of these drawings is now in the Archiwum Akt Nowych in Warsaw. About 100 pictures are in the Polish Embassy in Copenhagen.

— Iris Helbing, Ausstellungen (Exhibitions)[24]

World Vision in Germany has dedicated a still up-to-date traveling exhibition to war children. The exhibition, called "ich krieg dich" – "children affected by war"[25] – has so far been shown in New York, Brussels, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Bremen, Rostock and Münster. In 2015 it was shown in Tröglitz,[26] a small town in Saxony-Anhalt (Germany) whose mayor had resigned in March of 2015 to protect himself and his family from right-wing Neo-Nazi attacks. A month later, a planned refugee shelter was ignited[27] and in June the exhibition came to the town. It documents the life and world of children in war zones, highlighting four themes: home, everyday life, school and health. The exhibition's aim is to show "how violence, displacement and destruction" affect children and adolescents,[26] focusing on Syrian refugee children. The singer Kirk Smith and a six-person gospel choir from Florida gave a benefit concert at the opening of the exhibition.[28] World Vision has produced two videos, one on the topic of war children[29] and one on the opening of the exhibition.[30]

In 2009, the Museum of Military History (HGM) in Vienna had begun to address the subject of war children. This project was conceptualized when it was observed that some young people had begun to glorify war and that children used language about war weapons without being able to understand the meaning of the words. A video, published in November of 2016, became part of a special exhibition Children in War – Focus: Syria. It tells the story of the project, the experiences of the witnesses – children and adolescents – from Syria, as well as the reactions of the students and their teachers who had attended the exhibition.[31] They had the opportunity to speak with the witnesses, watch documentary films from Syria, and view the drawings of Syrian children, who – with children's naivety – had brought the cruelty of war to paper. In order to avoid possible traumatization of the visitors, the exhibition was limited to youth over the age of 13, as recommended by military psychologists. In February of 2017, the HGM organized a week of action, on the topic of children in war, focusing on South Sudan. The aim of this exhibition was to provide "young people with insight into the problems of the present and to position the subject historically".[32]

Collections

In January of 2017, the War Childhood Museum,[33] founded by Jasminko Halilović, opened in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ambassador of the museum is the Bosnian tennis player Damir Džumhur who, as Halilović, experienced the Bosnian War as a child. The museum collects every-day items of these war children, including clothes and toys, drawings and letters, but also photographs and diaries. In addition, there are audio and video documentaries of interviews by those who witnessed the war as children. Part of the collection was exhibited in 2016 at the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Unicef estimated that of the 70,000 children who were living in Sarajevo at the time, about 40 % lost their lives, another 40 % watched as family members were killed and almost 90 % were forced to live in hiding in order to find shelter from the bombing.[34] In 2013, as a preamble to the founding of the museum, Halilović published a book that tells the stories of these war children.[35] It has now been translated into six languages. In German, it was published by Mirno More,[36] an organization for socio-educational peace projects.[37] The Center for South Eastern European Studies presented the book in November of 2013.[38]

Halilović dedicated his project – which inspired the book and the museum – to his friend Mirela Plocic, who was killed in 1994.[35] In December 2015, he provided further insights about his motivations regarding his engagement in the children of the Bosnian War to the magazine Guernica.[39]

Charities

Literature

The titles of the following publications have been translated from German into English and have been put in brackets.

- Horst Schäfer (2008) (in German), Kinder, Krieg und Kino. Filme über Kinder und Jugendliche in Kriegssituationen und Krisengebieten (Children, War, and Cinema. Movies about children and youth in war situations and crisis areas), Konstanz: UVK-Verlagsgesellschaft, ISBN 978-3-86764-032-9

- Barbara Gladysch (2007) (in German), Die kleinen Sterne von Grosny. Kinder im schmutzigen Krieg von Tschetschenien (The Little Stars of Grosny. Children in the dirty war in Chechnya), Freiburg, Br., Basel, Wien: Herder, ISBN 978-3-451-29004-6

- Jan Ilhan Kizilhan (2000) (in German), Zwischen Angst und Aggression. Kinder im Krieg (Between Fear and Aggression. Children in War), Bad Honnef: Horlemann, ISBN 978-3-89502-118-3

- Sabine Bode (2013) [2004] (in German), Die vergessene Generation – Die Kriegskinder brechen ihr Schweigen (The Forgotten Generation – The war children are breaking their silence), München: Klett-Cotta, ISBN 978-3-608-94797-7

- Sabine Bode (2013) [2009] (in German), Kriegsenkel. Die Erben der vergessenen Generation (Grand-Children of War. The heirs of the forgotten generation), Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, ISBN 978-3-60894808-0

- Ludwig Janus, ed. (2006) (in German), Geboren im Krieg. Kindheitserfahrungen im 2. Weltkrieg und ihre Auswirkungen (Born During the War. Childhood experiences and consequences), Gießen: Psychosozial, ISBN 978-3-89806-567-2

- Jean-Paul Picaper, Ludwig Norz (2005) (in German), Die Kinder der Schande. Das tragische Schicksal deutscher Besatzungskinder in Frankreich (Children of Shame. The tragic fate of children in France whose fathers were members of the occupying German military), München, Zürich: Piper, ISBN 978-3-492-04697-8

- Heela Najibullah (2017), Reconciliation and Social Healing in Afghanistan. A Transrational and Elicitive Analysis Towards Transformation, Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, ISBN 978-3-658-16931-2

- Yury Winterberg, Sonya Winterberg (2009) (in German), Kriegskinder. Erinnerungen einer Generation (War Children. Memories of a generation), Berlin: Rotbuch, ISBN 978-3-86789-071-7

- Detlef R. Mittag (1995), Internationale Liga für Menschenrechte, ed. (in German), Kriegskinder. Kindheit und Jugend um 1945. Zehn Überlebensgeschichten (War Children. Childhood and youth around 1945. Ten stories of survivors), Berlin

- Adriana Altaras (2016-05-19), "Ausflug ins Land der Dichter und Henker (Journey into the Land of Poets and Hangmen)" (in German), Zeit Online, http://www.zeit.de/freitext/2016/05/19/buchenwald-weimar-dichter-henker-altaras/. Retrieved 2017-01-24

- Bettina Alberti (2010) (in German), Seelische Trümmer. Geboren in den 50er- und 60er-Jahren: Die Nachkriegsgeneration im Schatten des Kriegstraumas (Mental Ruins. Born in the 50's and 60's: The post-war generation in the shadows of the war trauma), München: Kösel, ISBN 978-3-466-30866-8

- Dietrich Bäuerle (2011) (in German), Kriegskinder. Leiden – Hilfen – Perspektiven (War Children. Suffering - Supports - Perspectives), Karlsruhe: Von-Loeper, ISBN 978-3-86059-433-9

- Heike Möhlen (2005) (in German), Ein psychosoziales Interventionsprogramm für traumatisierte Flüchtlingskinder. Studienergebnisse und Behandlungsmanual (A Psycho-Social Intervention Program for Traumatized Refugee Children. Research results and treatment manual), Gießen: Psychosozial, ISBN 978-3-89806-413-2

- Werner Remmers, Ludwig Norz, ed. (2008) (in German), Né maudit – Verwünscht geboren – Kriegskinder (Cursed at Birth – War Children), Experienzawast 2, Berlin: C & N, ISBN 978-3-939953-02-9

- Werner Remmers, Ludwig Norz (2013) (in German), Kriegskinder – enfants de guerre – children born of war, Experienzawast 3, Berlin: C&N, ISBN 978-3-939953-05-0

- Winfried Behlau, ed. (2015) (in German), Distelblüten. Russenkinder in Deutschland (Thistle Blossoms. Russian children in Germany), Ganderkesee: con-thor, ISBN 978-3-944665-04-7

See also

References

- ↑ "Conflict Barometer 2016" (PDF; 21.080 KB). Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK). p. 4. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ Die Kriegskinder: Aufwachsen zwischen Terror und Flucht on YouTube (in German) (Translation: Growing Up Between Terror and Escape)

- ↑ Sabine Bode (2004), "[The Forgotten Generation. The war children are breaking their silence]" (in German), Die vergessene Generation – Die Kriegskinder brechen ihr Schweigen, Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, ISBN 3-608-94800-7

- ↑ "Childhood in War Project. Research Project at the Munich University. 'Childhood during World War II and Its Consequences'". Munich University. 2003–2009. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ↑ Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, Jürgen Zinnecker, ed. (2007), "[Between Forced Labor, Holocaust and Expulsion: Polish, Jewish and German Childhood in Occupied Poland]" (in German), Zwischen Zwangsarbeit, Holocaust und Vertreibung: Polnische, jüdische und deutsche Kindheiten im besetzten Polen, Weinheim, München: Juventa, ISBN 978-3-7799-1733-5

- ↑ "Canadian Roots UK". Retrieved 2017-01-18. Canadian Roots UK assists war children who were born in Great Britain find their Canadian fathers. It also helps Canadian fathers find their possible children in Great Britain

- 1 2

Ariane Thomalla (2005-06-06). "Jean-Paul Picaper/Ludwig Norz: Die Kinder der Schande. Das tragische Schicksal deutscher Besatzungskinder in Frankreich" [Jean-Paul Picaper/Ludwig Norz:The Children of Shame. The tragic fate of children in France, whose mothers were French and their fathers members of the German military occupying France] (in German). Deutschlandfunk. Retrieved 2017-01-01.

200,000 so-called "German Children" are said to live in France. Today, they are between 59 and 64 years old. At an age when one looks back at one's life, they are searching for the other half of their identity. [...] Yet, it is believed that there are still harmful consequences, like lack of self-esteem, tendencies of self-hate and self-destruction […]. (Original: 200.000 so genannte ‚Deutschenkinder‘ soll es in Frankreich geben. Heute sind sie 59 bis 64 Jahre alt. In einem Alter, da man gern Lebensbilanz zieht, suchen sie nach der anderen Hälfte ihrer Identität. […] Dennoch gäbe es noch immer Folgeschäden wie mangelndes Selbstbewusstsein und Tendenzen des Selbsthasses und der Selbstzerstörung […])

- ↑

See

- Sascha Lehnartz (2009-08-06). "Deutsche Staatsbürgerschaft für einen 'Bastard'" [German Citizenship for a "Bastard"]. Welt N24 (in German). Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- Jean-Paul Picaper, Ludwig Norz (2005) [2004 Paris] (in fr), Die Kinder der Schande. Das tragische Schicksal deutscher Besatzungskinder in Frankreich [Enfants maudits: Ils sont 200,000, On les appelait les, enfants de Boches‘], Michael Bayer (trans.), München, Zürich: Piper, ISBN 978-3-492-04697-8

- "Amicale Nationale des Enfants de la Guerre" [National Association of War Children] (in French). Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- ↑ Thorsten Knuf (2010-05-05). "Sie wuchsen in Frankreich, Belgien oder Skandinavien auf. Ihre Mütter waren Einheimische, ihre Väter hatten für Hitler gekämpft. Jetzt, im Alter, wollen viele Nachkommen von Wehrmachtssoldaten Klarheit über ihre Herkunft haben – und manche sogar einen deutschen Pass. Kinder des Krieges" [They grew up in France, Belgium or Scandinavia. Their mothers were locals, their fathers had fought for Hitler. Now, in old age, many descendants of Nazi soldiers want to know more about their origins – and some even have a German passport.]. Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ↑ Frankreich: Der deutsche Pass on YouTube (in German) (Translation: France: The German Passport)

- ↑

See beside others

- Jarina Kajafa (2015-12-31). "Krieg in der Ostukraine. Mit Puppen gegen Minen" [War in East Ukraine. With Dolls Against Mines]. Taz (in German). Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- "UNICEF: Landminen sind tödliche Gefahr für Kinder" [Landmines Are a Deadly Danger to Children]. Entwicklungspolitik Online (in German). 2004-11-29. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ↑

"In Schweden fallen Flüchtlingskinder in Koma-ähnlichen Zustand" [In Sweden refugee children fall into a coma-like state]. Die Welt. 2017-04-03. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

Experts agree that these symptoms are not faked. However, there are no known cases outside of the country, and there is no explanation for these events. (Original: Der Konsens unter Fachleuten herrscht, dass diese Symptome nicht vorgetäuscht werden. Jedoch gibt es keine bekannten Fälle außerhalb des Landes, ein Umstand, der bis heute nicht erklärt werden kann.)

- ↑ Das Schicksal der Kindersoldaten on YouTube. ZDF (1:25) (in German) (Translation: The Fate of the Child Soldiers)

- ↑

"Minderjährige Kämpfer. Weltweit gibt es 250.000 Kindersoldaten" [Underage Fighters. Worldwide there are 250,000 child soldiers.]. Stern (in German). 2015-02-12. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

Every year, tens of thousands of children and adolescents are recruited as soldiers and forced to fight. [...], a ‘less costly alternative to adult soldiers’ (Original: Jedes Jahr werden Zehntausende Kinder und Jugendliche als Soldaten rekrutiert und zum Kämpfen gezwungen. […] ‚Preiswertere Alternative zu erwachsenen Soldaten‘.)

- ↑

"Unicef klagt an. IS, Terroristen, Afrika-Armeen: So brutal werden Kinder als Soldaten missbraucht" [Unicef Accuses. IS, Terrorists, African armies: That's how brutally children are abused as soldiers.]. Focus Online (in German). 2015-02-12. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

In the civil wars in South Sudan and the Central African Republic, 22,000 children and young people were deployed as soldiers last year, according to estimates by the International Children's Fund UNICEF. In Syria and Iraq, the Islamic State terrorist militia recruits minors and trains them for combat – some of them only eight years old. (Original: In den Bürgerkriegen im Südsudan und in der Zentralafrikanischen Republik waren im vergangenen Jahr nach Schätzungen des internationalen Kinderhilfswerkes Unicef 22.000 Kinder und Jugendliche als Soldaten im Einsatz. Auch in Syrien und im Irak wirbt die Terrormiliz Islamischer Staat gezielt Minderjährige an und trainiert sie für den Kampf – manche von ihnen sind erst acht Jahre alt.)

- ↑

"Rote Hände aus dem Bundestag" [‘Red Hands’ from the German Government] (in German). Red Hand Day. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

The German Military continues to recruit about 1,000 minors each year, providing weapon training to them. According to the valid UN definition, these are child soldiers.) (Original: Die Bundeswehr rekrutiert weiter jedes Jahr etwa 1000 Minderjährige und bildet sie an der Waffe aus. Nach der gültigen UN-Definition sind dies Kindersoldaten.)

- ↑

The photo and its history

- Nick Út (1972-06-08). "Pressefoto von Phan Thị Kim Phúc" [Press Photo of Phan Thị Kim Phúc] (in German). Word Press Foto. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- Horst Faas, Marianne Fulton. "The survivor Phan Thị Kim Phúc and the photographer Nick Út". pp. 1–7. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- "I've Never Escaped from That Moment: Girl in napalm photograph that defined the Vietnam War 40 years on". Mail Online. 2012-06-01. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

But beneath the photo lies a lesser-known story. It's the tale of a dying child and a young photographer brought together by chance.

- ↑ "Kinder im Krieg will niemand sehen" [No One Wants to See Children in War] (in German). UNICEF. 2010. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ↑ See Museum of Military History, Vienna

- ↑ Andrea Müller (2015-10-24). "Das Schicksal der Kriegskinder" [The Fate of the War Children]. Der Westen (in German). Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ↑

Beside others

- Imre Kertész (2010), "[Story of a Person Without Fate]" (in German), Roman eines Schicksallosen, Christina Viragh (trans.) (24 ed.), Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-499-22576-5, http://www.netz-gegen-nazis.de/seite/buecher-zum-download. Retrieved 2017-01-24

- Hans-Ulrich Treichel (1999), "[The Lost One]" (in German), Der Verlorene, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, ISBN 978-3-518-39561-5

- ↑ "Kinder im Krieg. Polen 1939 bis 1945" [Children During War. Poland 1939 to 1945.] (in German). Zeitzeugen-Projekte. 2012. Retrieved 2017-01-23. (in German, with videos and art work by children)

- ↑

Iris Helbing (2010). "Ausstellungen. Kinder im Krieg Polen 1939-1945" [Exhibits. Children During the War. Poland 1939 to 1945] (in German). Retrieved 2017-01-23.

Die Zeichnungen galten damals als wichtiges Material um die nationalsozialistischen Verbrechen an polnischen Kindern aufzuklären und zu dokumentieren. Der größte Bestand dieser Zeichnungen liegt heute im Archiwum Akt Nowych in Warschau. Circa 100 Bilder befinden sich in der polnischen Botschaft in Kopenhagen.

- ↑ Kage, Christian (2011-10-20). "ich krieg dich – Ausstellung in Berlin" [‘I Get You‘ Exhibition in Berlin]. World Vision Blog (in German). Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- 1 2 ""ich krieg dich" – Kinder in bewaffneten Konflikten. Unsere Ausstellung für Sie" [‘I Get You’; Children in Wartorn Conflicts. Our Exhibition for You.] (in German). World Vision Deutschland. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ↑ Melanie Reinsch (2016-04-04). "Tröglitz will nur vergessen werden" [Tröglitz Just Wants to be Forgotten]. Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ↑ "Tröglitz singt für Weltoffenheit" [Tröglitz Sings for Global Openness]. Welt N24 (in German). 2015-06-02. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ↑ Kinder im Krieg – „ich krieg dich". World Vision Ausstellung in Tröglitz on YouTube (in German) (Translation: Children in War – ‘I Get You’. World Vision Exhibition in Tröglitz)

- ↑ Benefizkonzert und „ich krieg dich" – Ausstellungseröffnung in Tröglitz on YouTube (in German) (Translation: Benefit Concernt and ‘I Get You‘ – Opening of Exhibition Tröglitz)

- ↑ Kinder im Krieg – Fokus: Syrien on YouTube (in German) (Translation: Children During War – Focus: Syria)

- ↑ "Aktionswoche 'Kinder im Krieg'. Themenschwerpunkt: 'Südsudan'" [Week of Action: ‘Children During War’. Thematic Focus: "South Sudan"] (in German). Heeresgeschichtliches Museum. Militärhistorisches Institut. 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ↑

"War Childhood Museum". Retrieved 2017-03-29.

The War Childhood Museum opened in Sarajevo in January 2017. The Museum‘s collection contains a number of personal belongings, stories, audio and video testimonies, photographs, letters, drawings and other documents, offering valuable insight into the unique experience of growing up in wartime.

- ↑

Dan Sheehan (2015-12-15). "Jasminko Halilović: Children of War". Guernica. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

UNICEF estimated that of the approximately 70 000 children living in the city during the period, 40 percent had been shot at, 39 percent had seen one or more family member killed, and 89 percent had been forced to live in underground shelters to escape the shelling.

- 1 2 "War Childhood: Sarajevo 1992–1995". Jasminko Halilovic. 2013. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ "Mirno More Friedensflotte" [Mirno More Flotilla of Peace] (in German). Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑

"Book 'War Childhood: Sarajevo 1992–1995'". War Childhood Museum. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

After two and a half years of work on the project, the ultimate aim was achieved – illustrated book on 328 pages brings stories of generations that grew up during the war.

- ↑

"War childhood. Sarajevo 1992-1995" (in German). Zentrum für Südosteuropastudien der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. 2013-11-20. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

The book is the result of an inter-active project. Its goal was to collect common experiences and memories of children in Sarajewo. (Original: Das Buch ist Resultat eines interaktiven Projekts, dessen Ziel es war, kollektive Erfahrungen und Erinnerungen von Kindern in Sarajevo zu sammeln.)

- ↑ Dan Sheehan (2015-12-15). "Jasminko Halilović: Children of War". Guernica. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Children in war. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Child soldiers. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Children of Iran in Iran-Iraq War. |

- Canadian Roots UK (war children in England are looking for their Canadian fathers)

- Amitié Nationale des Enfants de la Guerre (German-French association of war children)

- Born of War international Network

- Kriegskinder e.V. Forschung – Lehre – Therapie (German)

- Kriegskind.de (German)