Percy Charles Pickard

| Percy Charles Pickard | |

|---|---|

P. Charles Pickard | |

| Nickname(s) | "Pick" |

| Born |

19 May 1915 Handsworth, Sheffield, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died |

18 February 1944 (aged 28) Amiens, France |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1937–1944 |

| Rank | Group Captain |

| Commands held |

No. 140 Wing RAF No. 51 Squadron No. 161 Squadron |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards |

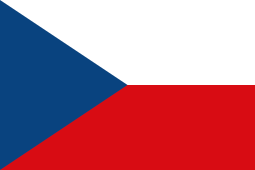

Distinguished Service Order & Two Bars Distinguished Flying Cross Mentioned in Despatches Czechoslovak War Cross 1939 |

Group Captain Percy Charles "Pick" Pickard, DSO & Two Bars, DFC (16 May 1915 – 18 February 1944) was an officer in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. He served as a pilot and commander. He was the first officer of the RAF awarded the DSO with two bars in the Second World War. He flew over a hundred sorties and distinguished himself in a variety of operations requiring coolness under fire.

In 1941 he participated in the making of the 1941 wartime film Target for To-night, which made him a public figure in England. He led the squadron of Whitley bombers that carried paratroopers to their drop for the Bruneval raid.

Throughout 1943 he flew the Lysander on nighttime missions into occupied France for the SOE, performing insertions of agents and picking up personnel from very small landing strips. Pickard led a group of Mosquitos on the Amiens raid, in which he was killed in action 18 February 1944.

Early life

Pickard was born in Handsworth, Sheffield, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England, the son of Percy Charles Pickard and his wife Jenny. He was the youngest of five children, with an older brother and three older sisters. His father, a Yorkshireman, was a stone merchant. In 1920 the family moved to Hampstead, north London, where Pickard's father began a successful catering business. Having the same name as his father and being the youngest in the family, he was affectionately referred to as 'Boy', and the family nickname persisted, even as he grew to be 6' 4".[1] He was sent to Framlingham College.[2] His older brother, Walter, joined the RAF and became an officer. His oldest sister "Pixie", Helena Pickard, became an actress. She married well-known actor Sir Cedric Hardwicke.[2]

Though bright and engaging, Pickard struggled with both reading and writing, leading some to believe later that he may have struggled with dyslexia.[3] He was enthusiastic in school sports, and excelled at shooting, but by far his favourite activity was riding horses.

The father of one of Pickard's schoolmates at Framlingham owned a farm in British East Africa, and offered his son to bring a classmate along when he came out to work on the farm once they graduated from college. Pickard took up the offer, and arrived in British East Africa in 1932.[4] The schoolmate returned after a year, but Pickard stayed on. The vast grasslands provided ample opportunity for riding, which Pickard loved. Sidney Carlin, a fighter pilot with the Royal Flying Corps in the Great War, recruited Pickard and three of his friends to form a polo team, and he trained them in the game's skills.[5] Pickard excelled as a Polo player, earning a 3 handicap.[3] In November 1935 he joined the King's African Rifles as a territorial reservist.[4]

With the gathering dark clouds of war looming, Pickard and his friends from the polo team chose to return to England. Lacking the funds for a full passage, they drove their car north through Italian Somaliland, British Somaliland, Egyptian Sudan, finally arriving in Egypt. Along the way Pickard became gravely ill with Malaria and nearly died. They had to stop for some time until he could recover, but the group eventually made it to Alexandria. There they obtained transport across the Mediterranean to Marseille. From there they drove across France to reach the channel, and then by ferry to England.[3] Once he arrived he volunteered to serve as an officer with the Army, but was declined on account of his poor school results. He then applied to the Royal Air Force, who were in the midst of a massive expansion. He was granted an RAF short service commission in 1936. After initial flying training he was posted to 214 Squadron, equipped with the Handley Page Harrow bomber.[3] He received a commission as Acting Pilot Officer 25 January 1937.[6] The posting of Pilot Officer was confirmed and made permanent 16 November 1937.[7] He was posted to Bomber Command.[4]

During this period he met and began seeing Dorothy Hodgkin. Her family did not approve of the couple, and Dorothy soon left home to live on her own. Living in a tiny apartment and short of funds, Pickard found her and let her know that his sister, Helen, was looking for an assistant. Dorothy took the job, which led to others.[8] The following year they became engaged, and wed in a small ceremony. His wedding present to her was a large Old English Sheepdog to keep her company while he was away. They called the dog 'Ming'.[1]

Pickard trained with 214 Squadron for a short time before being appointed ADC to Air Vice Marshal John Baldwin in 1938, who was commander of the training group at Cranwell. A year later, in October 1939, Pickard was posted to 7 Squadron flying Hampden bombers at RAF Upper Heyford.[3] Shortly thereafter he was returned to 214 Squadron. This squadron was disbanded to form an operational training unit, and he briefly returned to 7 Squadron before being posted to 99 Squadron at Newmarket Heath. He remained with 99 Squadron through the first year of the war, flying one of the best bomber aircraft available at the time, the Vickers Wellington.[9]

First tour with No. 99 Squadron

In the early stages of the war prior to the German invasion of France Bomber command was reticent about escalating the war by launching major attacks on German cities. Instead they confined their command to leaflet drops and coastal patrols. With the German invasion of Denmark and Norway the command became more active. Flying Vickers Wellingtons with 99 Squadron, Pickard participated in fighting over Norway, France and during the Dunkirk evacuation. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in July 1940.[2]

Bomber Command's early daylight raids deeper into Germany revealed that the defensive armament of the bombers was inadequate to defend them against German fighter aircraft. Stanley Baldwin's axiom “The bombers will always get through” was proven false. After suffering significant losses the bombers were withdrawn from daylight attacks.[10] Both the British Army and the Royal Navy were desperate for aircraft to help them in their respective endeavors, and bomber command's strength was attenuated as aircraft were shifted away to the Navy to help with submarine patrols, and to the Army to help in the Western Desert.

Still convinced that "strategic" bombing was a war winning strategy, Bomber Command moved its bombing campaign against Germany to night missions. Though much safer to the aircrews, flying at night eliminated many of the visual clues to navigation, making it much harder to find and attack the target. Foul weather could cloak targets as well, and the industrial Ruhr valley area generated enough haze from its factories to keep the region in a constant shroud of fog. England's notorious bad weather also added to the danger, making finding and setting down on the home airfield significantly more dangerous. Bomber Command lacked navigational abilities, and the results of the raids were unknown to the crews.

Navigational techniques slowly improved, crews became better, as did German night defences.[9] As navigation improved so did their ability to reach and deliver bombs on target. It was during this period that Pickard met and befriended fellow Yorkshireman navigator Alan Broadley, who was to become his good friend and comrade to the end.[11] Thereafter when Pickard transferred to an operational squadron he would always ask for Broadley to be transferred into the squadron as well. Pickard was calm when under fire, and gained a reputation for pressing on to his objective regardless of the difficulties. Aircraft service crews grew accustomed to Pickard and Broadley returning in an aircraft that had been peppered with flak and night fighter damage.

Through the campaign in the air Pickard had settled down to a fairly comfortable life living on base with his wife Dorothy and their English Sheepdog ‘Ming.’[9] The airfield at Newmarket was sited over the Newmarket Racecourse, and with horse racing suspended due to the war, Pickard was able to acquire two thoroughbreds at low expense.[9] Dorothy and Pickard often rode together. Each morning would find them out for a ride in the country, whether he had flown the night before or not, with Ming running alongside them.

On one of his nighttime missions, 19 June 1940, the squadron attacked the Ruhr. Pickard's Wellington was hit by anti-aircraft fire and one engine was seriously damaged. Losing altitude, he was able to nurse the aircraft past the coast but ended up having to ditch in the North Sea. The crew escaped alive and all entered a rubber dinghy. After a number of hours they were located by an RAF High Speed Launch from Felixstowe. Unfortunately, Pickard had set down in a mined area.[12] It took several more hours for them to drift out from among the mines so they could be picked up.[13] In all they spent 14 hours in the bitter cold of the North Sea.[11]

The most common complaint of aircrews involved in the RAF's bomber campaign against Germany was of exhaustion. This stemmed from the stress of both the missions themselves and the difficulty of returning to land at night in England’s notorious bad weather. Pickard never seemed troubled by this. No record of Pickard or Broadley notes either ever complaining of exhaustion.[9] By the end of November, Pickard and Broadley had completed 31 sorties and were rotated off to non-operational duties. Pickard, however, was soon looking to return to operational flying.[9]

Pilot instruction of No. 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron

With the completion of his first tour he was promoted to Squadron leader and transferred to a training position, working to train pilots in the 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron. Operating out of RAF East Wretham, 311 Squadron was not fully operational. Most of their flights were coastal patrol missions, but as part of the training process from time to time the crews were sent along with combat squadrons on missions over Germany. On September 24 the squadron carried out its first operation to the ‘Big City’ (Berlin).[3]

Pickard proved a hard taskmaster and persistent instructor. He routinely went along as an observer when one of his pupils took their first combat flights into Germany. As he was a "ride along" instructor, these sortie flights were off the book and did not add to Pickard’s sortie totals, though the risks were real enough. One problem that came to light was the language barrier. Pickard chose to concentrate his efforts on those pilots with the most experience flying. An interpreter told him of one Czech with 2000 hours flying experience. Pickard turned his attention to him. After several trips with the man he proved strangely inept for a man with 2000 hours flying under his belt. Finally Pickard's patience wore out. He ripped into his charge for being so incompetent in take-offs and landings, only to discover that the man's prior experience was actually as a navigator. He had no piloting experience at all. Surprised but undeterred, Pickard pressed on and trained him to be a pilot anyway.

At about this time Crown Productions was doing a movie on the bomber campaign. Pickard was an experienced pilot available, and had acting in his family. He was asked to play the pilot for the production of Target for To-Night, and became widely known as the pilot of the bomber “F-Freddie”.[9] The movie was a success, and made him a national hero.[1][14] Upon completion of the film in April 1941, Pickard returned to operations.[3]

For his service with 311 Squadron he received his first Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in March 1941.[2] He was also awarded the Czech Cross.[1]

Second tour with No. 9 Squadron

On 14 May 1941 Pickard was assigned to 9 Squadron. He was joined there by Broadley, who by now had become a commissioned officer. The squadron was based at Honington, and flew the Wellington. Another grueling tour of operations followed. In the night skies over Germany in the summer of 1941 they flew against major German targets such as Hamburg, Düsseldorf and Cologne.[15] At the time, only about 30% of aircrews survived to the end of a 30 sortie tour of combat. By the end of August Pickard had flown another 33 sorties with Broadley, bringing his total to 64. This number did not include those missions he flew with the Czechs.[9]

With the end of his second tour Pickard was rotated off again. He was assigned 3 Group Headquarters as a shuttle pilot flying senior command officers between airbases, but took no pleasure in such service.[9] Having completed two operational tours, Pickard and Broadley had fulfilled their operational requirements, and need not have flown any more operations. On his leave he visited a pilot friend of his, Flight Officer Hockey, who was with 138 (Special Duties) Squadron at RAF Newmarket. Pickard was able find a spot flying two clandestine missions as a second pilot.[16] He had a keen desire to continue on operations, and soon managed to talk his way back into an operational unit.

No. 51 Squadron and Operation Biting

Pickard joined 51 Squadron at RAF Dishforth in November 1941. The aircraft being used by the squadron were Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys, but the role of the squadron was photographic reconnaissance rather than bombing. The squadron’s aircraft had been modified to carry high resolution photographic equipment to assess targets and evaluate bomb damage. Pickard flew a number of these missions, including one over the French port of St. Nazaire, but was soon tasked with leading his squadron on a special mission.

German air defenses had been improving, and they were making use of a new radar, the Würzburg air defence radar, which was very effective. It provided both angular accuracy and altitude accuracy, which made for effective anti-aircraft fire control in all weathers. The Wurzburg "seeing eye" was good enough to pick up a single heavy bomber at 35 kilometers and transmit continuous range, bearing and elevation data automatically to the computing device (the "Kommandogerät"). Bomber command's losses were mounting, and their defence scientists wanted to learn how the device worked.[9] One such station had been positioned on a bluff overlooking the French coast at Bruneval, near Le Havre. Lord Mountbatten set to planning the Bruneval raid.[17]

In January 1942 Pickard and his squadron began training for a low level operation over occupied France. Their Whitley bombers had been modified with holes cut in the fuselage to allow paratroopers to jump directly out of the bottom of the aircraft. On the evening of 27 February Pickard led a group of 12 Whitleys, picking up the paratroopers at RAF Thruxton and taking them over the English Channel to France.[18]

The channel crossing went off without incident, but their aircraft came under anti-aircraft fire as they reached the French coast. None of the aircraft were hit, and they successfully delivered C Company to the designated drop zone near the installation.[19] The mission was successful. Back in England, Pickard went down to Portsmouth to personally greet the returning British paratroops at the dock.

In May 1942 he was awarded his first bar to his DSO for this action.[9]

No. 161 (Special Duty) Squadron at RAF Tempsford

.jpg)

Pickard's next tour was possibly the most dangerous, working in the secretive Royal Air Force Special Duties Service as commanding officer of 161 (Special Duties) Squadron. Pickard assumed command in October 1942. 161 Squadron together with 138 Squadron were tasked with missions of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).[11] Their primary role was to serve as a transport service in and out of occupied Europe. Initially they brought to France agents whom they had trained in the selection of fields suitable for the landing and taking off of their aircraft. The agents chosen were all fluent in French so they could blend in. Most of these agents were French expatriates. Some of them had been pilots in the French Armée de l'Air. Once the agent was in place and had selected a number of potential locations for the landings, 161 Squadron would deliver SOE agents, wireless operators, wireless equipment and weapons to assist the resistance. Out of France they transported French political leaders, leaders of the resistance or their family members, and the occasional downed allied airman.[20]

The Westland Lysander was the principal aircraft used for pick-ups of resistance agents, VIPs and downed airmen.[21] The Lysander excelled in low-speed handling characteristics, had a very low stall speed and excellent short field take off and landing capabilities. It was flown single-handed and without navigational aides. The missions had to be flown on nights with a full or near full moon. The pilot navigated by compass and with a map held on his knees. The plane could carry one to three passengers in the rear.

The greatest difficulty for the pilots was the weather, as the pilot had to navigate by himself, reading a map and comparing it to the terrain below. The pilots laid out their routes in a series of legs to easily recognizable terrain features they called pin points. The route made avoided areas where German flak positions were present. If there was extensive cloud or fog it was impossible to pick out the terrain features needed to navigate to the target. The best terrain feature was always a body of water, as its surface shimmered and appeared silver in the moonlight. These were long, slow flights in the dark to reach poorly lit fields. German night fighters were also a hazard, and one never knew when landing if you would be greeted by the resistance or the Gestapo.[9]

RAF Tempsford was designed to look like an ordinary working farm. SOE agents were lodged in a local hotel before being ferried to farm buildings that had been built within the perimeter of the airfield track, an unusual feature for an RAF airfield. This was the "Gibraltar Farm". After final briefings and checks at the farm, the agents were issued firearms in the barn, and then boarded onto an awaiting aircraft flown by one of a team of pilots such as Pickard.

Although the squadron was based at RAF Tempsford in Bedfordshire, the squadron often moved forward to RAF Tangmere, the squadron’s forward operating base, during periods of the full moon.[3] Tempsford was the home base and training area of the squadrons. The airfield there became the RAF’s most secret base.[9] When on operations the Lysander flight of 161 Squadron moved forward to RAF Tangmere, which was situated close to the coast and shortened their flights. Tangmere airfield was the home base for a pair of fighter squadrons. 161's Lysanders were parked off in their own area away from the field's normal operations. The SOE placed their people in Tangmere Cottage, located opposite the main entrance to the base.

Called the 'Tempsford Taxis', their operations did not always run smoothly. On one occasion Pickard found cloud cover made it impossible to locate the field. He circled the area for almost two hours before a break in the cloud appeared and he made his landing. He barely made it back with his passenger, as he had used up most of his fuel. On another occasion he was caught on his return flight by a pair of German night-fighters. Using his low stall speed and timing his turns he forced the fighters to overshoot and miss him time and again. Their attack was finally broken off when a flight of British fighters that had been scrambled to escort Pickard intercepted them over the channel.

In February 1943 a trip to collect two agents from a field near Tournai was made difficult on account of thick fog. He continued to circle for well over an hour until finally he found a hole and set the aircraft down. Having loaded his passengers, the aircraft became bogged down in mud. It took over two hours, and most of the occupants of a nearby village to get him out of the mud and into the air again. Using full power he managed to get airborne.[3]

One of the men picked up on this trip was René Massigli, who later served in London as Charles de Gaulle's Commissioner for Foreign Affairs.[22] Another man Pickard picked up around this time was General de Lattre de Tassigny, who commanded French and American troops in the fight across France.[23]

Pickard's arrival at 161 Squadron coincided with a marked uptick on the squadron's operative success rate, and an infusion of optimism and ambition. Said Pilot Officer Jimmy McCairns, "We all felt that we were destined to attain even bigger and better results."[24] Pickard was also instrumental in introducing the larger Lockheed Hudson into pick-up operations. If larger parties needed to be picked up, 161 Squadron had to send two aircraft in what they termed "a double". Pickard determined that the Hudson's stall speed was actually some 20 mph slower than the manual stated. With Squadron Leader Hugh Verity, he worked out the operating procedures that enabled this twin-engined aircraft to operate from French occupied fields, giving them the ability to carry in and bring out more people in one mission with a single aircraft.[3]

On 13 January 1943 Pickard carried out the first Hudson operation, flying five agents into a field near the River Loire.[3] Special Duty Squadrons 138 and 161 transported 101 agents to occupied France, and recovered 128 agents, diplomats and airmen from occupied France.[25]

On finishing his tour with 161, Pickard was awarded his third Distinguished Service Order. He was the first airman in the RAF to be awarded three DSOs in the Second World War.[3]

RAF Lissett

By May 1943 Pickard had amassed a total of 100 sorties, and Broadley had 70. They both had completed their second tour and were again taken off operations.[9] Pickard was promoted to the rank of Group Captain.[3]

In late 1943 the RAF was beginning to make preparations for a return to the continent. Pickard, however, was not a part of it. He was posted to command RAF Lissett, home of 158 Squadron, where he stayed through the summer of 1943. Command of an airfield was not to his liking. When his wife arrived he soon expressed his feelings on the matter: "I'm not staying on this bloody station. There's no operational flying and I've just had it. I'm getting transferred, so don't bother looking for a house here. You can go back to Tempsford for now. I've had more excitement chasing rabbits and washing nappies!"[26]

Pickard began writing letters to various commands to see if he could get posted back to an operational squadron. His efforts bore fruit at the foot of Air Vice Marshal Basil Embry, commander of 2 Group, a part of the newly formed Second Tactical Air Force. Embry was an active officer himself, and even though a senior staff member and forbidden to go on ops, he would often fly along as "Flight Officer Smith". Embry took a liking to Pickard, and gave him the chance he was looking for. He requested Pickard be posted to his command, and in October 1943 Embry gave Pickard command of 140 Wing based at RAF Sculthorpe in Norfolk.[9]

Pickard's new command comprised three squadrons of de Havilland Mosquitos, one of the fastest bomber aircraft of the war. The Mosquito was a versatile aeroplane and had a long track record in the Pathfinder Force. 140 Wing was putting it to a new use: daylight low-level precision bombing of special targets.[9]

No. 140 Wing and the Mosquito

Pickard took command of the newly formed 140 Wing in October 1943 as the unit's first commanding officer. 140 Wing consisted of three squadrons: 21 Squadron RAF, the Australian 464 Squadron RAAF, and the New Zealand 487 Squadron RNZAF.[9] The airmen of 140 Wing gave Mosquito "EG F" to Pickard as a nod to his 1941 appearance in the Crown Film Target for To-Night.[3] Pickard was checked out in the Mosquito and was soon cleared to fly.

From October 1943 Pickard led a number of low level daylight raids against targets in France.[9] In one such mission to destroy the power station at Pontchâteau, his Mosquito was struck by flak, causing the starboard engine to catch fire and seize up. Pickard cut fuel to the engine but with it seized he was unable to feather it. Despite the extra drag and loss of power he continued on to the target, released his bombs, and then nursed the aircraft back to RAF Predannack, some 370 miles away.[27] "F-Freddie" was out of commission for three weeks. Pickard continued on in other aircraft. Once repaired Pickard flew the aircraft on a mission against a set of river barges tied up on the Rhine at Cleves.[28] Again "F-Freddie" came back riddled with flak, putting her back in the hangar for repairs.[29]

During this early time at 140 Wing Pickard did something which is now almost a legend at his school. On the afternoon of 19 November 1943 he returned to his old school, Framlingham, flying his "F-Freddie" Mosquito to the nearby Parham airfield. The Framlingham graduate had become a hero at the school. In addition to his well known service with the RAF, the president of the school had established the practice of letting the school out each time the King bestowed another honour upon Pickard. The young man who had been a near washout at Framlingham returned to the college to address the boys, addressing a future England he had a premonition he would not live to see. One listener characterized his talk as “a most interesting and unvarnished account of his experiences, delivered in a notably human and intimate style and of absorbing interest”.[9]

On 1 December he was joined at 140 Wing by his navigator, Flight Lieutenant Alan Broadley.[15] In January 1944 his Mosquitos moved to Hunsdon. By the end of the month Pickard had led his wing on four more low level daylight attacks.[29] It was from Hunsdon that Pickard led the daylight attack of 18 February to bomb the prison at Amiens in France, in the raid known as Operation Jericho.

Amiens prison raid (Operation Jericho)

In February 1944 the RAF was given a special mission to bomb a Gestapo prison in Amiens, northern France. The circumstances involving the request and the true purpose of the mission remain among the secrets of the war. Reportedly the request came from the French resistance who had members in the prison who were scheduled to be executed. However, after the war an RAF probe revealed the French resistance leaders were first made aware of the raid when the RAF requested a detailed description of the target.[30] The French resistance acquired the information requested and transmitted it back to England, not knowing the purpose of the request. For his part, Pickard and his force were told it was imperative for them to undertake a precision daylight attack on the prison, destroying the guard barracks and blowing holes in the walls of the prison to allow French resistance prisoners held there to escape. The mission had to be completed before 19 February, as this was the day Embry was told the prisoners were to be executed.[12][30]

Embry had planned to lead the attack, having done so secretly a number of times despite his seniority. This time, however, he was strictly forbidden as he had knowledge of the D-Day invasion planning, and his capture was a risk that could not be accepted. The command of the raid then fell to Pickard.[9] The operation was to be conducted entirely at low level, 50 feet or less both inbound and homebound below the enemy radar.

Close escort for the fighter bombers was to be provided by Hawker Typhoons from 174, 245 and 198 Squadrons, with an additional squadron of Hawker Tempests flying cover over Amiens itself. The attack was scheduled for 16 February, to be made in three waves of six Mosquitos each. The first wave of attacking aircraft were to blow holes in the prison walls, the second wave was to destroy the guards' barracks. If these two failed to create the holes in the prison walls of the Amiens Prison, the third wave of attacking Mosquitos had the unusual duty of destroying the prison entirely, killing everyone inside.[9]

Embry would usually have flown as No. 2 in the lead formation, allowing the squadron leader to lead his men and giving Embry a little more freedom to observe the raid as a whole rather than concentrating on waypoints and so on. It is therefore natural to assume that Pickard would have initially planned to be in this slot. However, at the last moment the third wave’s orders were changed from "back up as directed" to "destroy the prison entirely," which would necessarily result in a heavy loss of life. This clearly troubled Pickard as the burden of responsibility for ordering the killing of many innocent prisoners now lay with Flight Lieutenant Tony Wickham, the pilot of the Film Production Unit Mosquito which was there to document the mission, whilst he, the senior officer, would in theory be flying at full speed back to Britain at that crucial moment.[30] Consequently, Pickard came up with a somewhat riskier plan to place himself in the number twelve position; at the very rear of the second wave.[12]

The attack was to be made at very low level, with bombs being dropped at a height of 10 feet off the ground.[31] The aircraft had to slow to just above their loaded stall speed at the time of bomb release so the bombs would not be destroyed by their impact with the ground. This was a significant risk in itself, as stalling while at such low altitude allowed no possibility for recovery. After bomb release the planes then had to pull up to clear the 20 foot high walls of the prison. Time delay fuses, with an 11-second delay, were used to allow the aircraft time to clear the target before their bombs exploded. The mission would be filmed by the on-board camera of a photo-recon Mosquito which had been attached for the raid.[30]

The mission was set for 16 February, but unusually wintry weather, with low cloud and snow meant the mission had to be scrubbed the first two days. 18 February was their last opportunity, and Pickard elected to go, despite the bad weather. In their pre-flight briefing Pickard told his men “When I have dropped my bombs I shall pull off to one side and circle, probably just to the north of the prison. I can watch the attack from there; and I’ll tell you by radio." None of the pilots were keen to fly on such a day. In his mild tone he added "It's a death or glory mission for us". 19 Mosquitos were sent on the mission: 6 aircraft of No 487 (RNZAF) Squadron, 6 aircraft of No 464 (RAAF) Squadron, 6 aircraft of No 21 Squadron and one aircraft of the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit.[31]

The first wave took off in appalling weather. Visibility was hampered by snow squalls.[12] The aircraft were initially flying blind till they broke through the cloud cover. Two aircraft of No 21 Squadron had to turn back to base before leaving the English coast due to engine problems.[31] The weather made it difficult to link up with their assigned covering fighters at the coast. The Typhoons assigned to cover the first group of Mosquitos were late to the rendezvous and did not link up, but the escort for the second group did.

Over the Channel the weather cleared and sunshine broke through. They crossed low at about 50 feet over choppy wave tops. Under strict radio silence, they had to maintain visual contact if they were to stay together. The Mosquitos flew in a compact formation. Meanwhile, the Hawker Tempest fighters from No 3 Squadron RAF assigned to provide air cover over Amiens itself never got into the air, their commander refusing to allow the squadron to take off into the complete whiteout over his airfield.[30]

As the raiders crossed over the channel the enemy coast was at first an indistinct line, but became clearer as the aircraft approached it. They climbed slightly to clear the cliffs and swept over the snow-covered fields near Tocqueville-sur-Eu.[13] They proceeded along their path over the French countryside. Visibility was around four miles and the cloud base was at 2,000 feet. They were flying so low that snow flew up in their wake as they passed. Reaching Senarpont, they made their hard left, then over the Somme river valley to make a bend at Bourdon toward Doullens. Reaching it they turned hard right toward Albert.

At 1159 the first wave reached Albert where one of their aircraft was hit by flak in its starboard engine nacelle. Losing power, it was forced to feather and abandon the attack.[31] The rest of the group made their final hard right to place them on course over the long, straight Albert-Amiens road to the target. Unfortunately, the formation had overshot the turning point at Albert, putting itself a few minutes behind schedule. Insignificant though this was in itself, it meant that the second wave, running on time, was now following too close and would arrive over the target just as the delayed action bombs of the first wave would detonate. Seeing his group close on the first wave, the leader of the second wave made a decision to take his six Mosquitoes around a two-minute circular orbit north of the road to burn off time and create a little space. Though the correct action for the flight, for Pickard at the tail end of the formation, it was a fateful decision.[12]

Just at this time a training flight of Fw 190s from JG 26 was airborne to the north of Amiens. It was redirected to investigate a raid heading towards them. Leading the German formation was Oberleutnant Waldemar Radener, who ordered his men to drop below the cloud layer to look for the raiders.[30] At 12.04 hours Radener and Feldwebel Wilhelm Mayer descended out of the cloud and spotted several Mosquitos and Typhoons beneath them. Radener quickly slipped unseen behind the Typhoon of Flying Officer Renaud of 174 Squadron and shot it down without the other RAF pilots even noticing. Mayer, meanwhile, slipped in behind six Mosquitos below him and attacked the last aircraft in the formation.

Pickard apparently saw the tracer shells fly past him as he immediately put his Mosquito into a hard banking turn to the left. Meyer followed; regaining a firing position, he let go with a second burst. This time the rear of Pickard's wooden fuselage was caught in a stream of cannon shells. The fuselage shattered and the tail section broke clean away, causing the Mosquito to flip over onto its back and crash into the ground.[1] The combat was over less than a minute after Meyer had broken cloud cover.[12]

No. 464 Squadron proceeded on to the target and delivered their bombs, apparently unaware that Pickard was no longer with them. Above them, Flight Lieutenant Tony Wickham piloting the PRU Mosquito, circled at 500 feet while the film officer recorded the damage. Wickham could see men running out of the prison across the snow covered fields.[31] With no word from Pickard, he gave the command calling off the third wave of Mosquitos, and turned for the coast and home. A few minutes later on their way out 464 Squadron came under fire near Frénouville. The Mosquito of squadron leader McRitchie attacked one of the gun positions. His aircraft was hit and shortly afterwards dropped to starboard. It was not seen again. McRitchie's aircraft had taken fire directly into the cockpit, and his navigator, Flight Lieutenant Samson, had been killed. McRitchie struggled to keep his aircraft aloft, but crashed near Dieppe where he was taken prisoner.[31]

Four aircraft were lost in the mission: two Hawker Typhoons and two Mosquitos.[32]

Operation Jericho was a success, but Pickard and his Navigator, Flight Lieutenant J. A. "Bill" Broadley, were killed. It was a devastating loss for 140 Wing.[30] The two men were initially reported missing in February, but in September the news was finally released that they had been 'killed in action'.[33]

The French wrongly assumed he had been posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. The letters VC had to later be removed from his gravestone. To mark his gallantry, the French also wished to award him the Companionship of the Légion d'honneur and the Croix de Guerre, but these awards were declined because of a British policy of refusing to accept posthumous awards from foreign nations.[1]

Pickard is buried in plot 3, row B, grave 13 at St. Pierre Cemetery near Amiens, France.[34] Broadley is buried in plot 3, row A, grave 11 of the same cemetery.

Personal

Percy Charles Pickard ranks among the likes of Guy Gibson and Leonard Cheshire as icons of Bomber Command.[12] Soon after the war began he had earned a reputation for boldness. Log book records show Pickard flew nearly 2200 hours during his RAF career in 41 different aircraft and carried out bombing raids and clandestine operations against the enemy on at least 103 occasions.[9]

He was the first airman in the RAF to be awarded three Distinguished Service Orders in the Second World War.[2] He was also the holder of the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Czech Military Cross.[1] Pickard's final commanding officer, Air Chief Marshal Sir Basil Embry, commented: "In courage, devotion to duty, fighting spirit and powers of really leading, Percy Pickard stood out as one of the great airmen of the war and as a shining example of British manhood."[1]

"His long operational career, covering many aspects of aerial conflict, included some of the most daring episodes in the RAF's history. In Air Force circles he was admired for his consistent leadership, determination and courage." - historical author Chris Hobbs

Growing up he was known as 'Boy' to his family, Charles to his school teachers, and 'Pick' to his friends and comrades. He was remarkably steady under duress. His friends described Pickard as “quiet, thoughtful, and seemingly imperturbable.” Among the RAF he was known for strong, quiet leadership and dogged determination. Mild tempered, with an ever-present pipe in his mouth, he was a man whose manner endeared him to both the general public and the men he commanded.[12]

A year after his death his family ran a notice in The Times to his memory, which read:

- In proud and glorious memory of our "Boy", Group Capt. P.C. Pickard, DSO, DFC, who with his brave and gallant Navigator for 4 1/2 years, Flt Lieut. Alan Broadley, DSO, DFC, DFM, did not return from Amiens a year ago today. Remembering also his many friends, whom he was not afraid to join. - Mother

- Horses he loved, laughter and the sun.

- A dog, wide spaces and the open air.[35]

- In proud and glorious memory of our "Boy", Group Capt. P.C. Pickard, DSO, DFC, who with his brave and gallant Navigator for 4 1/2 years, Flt Lieut. Alan Broadley, DSO, DFC, DFM, did not return from Amiens a year ago today. Remembering also his many friends, whom he was not afraid to join. - Mother

Honours

References

- Notes

- ↑ Pilot Instructor, 311 Czech Squadron, Royal Air Force. Citation reads: Since joining No. 311 Czech Squadron in July 1940, this officer has invariably taken out new Czech crews on their initial operation, or first long distance mission. On such occasions, he has been the only British member amongst the crews, who have been inspired by his splendid leadership and example. On one occasion it was undoubtedly due to his determined efforts that one Czech crew was rescued after being adrift in the North Sea for 13 hours. On another occasion when a crew was forced down in the North Sea, his persistence, and good airmanship in failing light, and his sound use of recognition signals, enabled surface craft to effect a rescue. His complete disregard for danger was particularly shown on an occasion when a fully loaded bomber crashed and caught fire. He led a rescue party and personally extricated two members of the crew, and succeeded in eventually conveying them to safety, although compelled to remain prone in the danger area during the explosion of some of the bombs. He has displayed coolness and courage of a high order and, by his magnificent work, contributed largely to the present efficiency of the Squadron.

- ↑ Acting Wing Commander, 51 Squadron, Royal Air Force. Citation reads: This officer has made his squadron an extremely efficient bombing force. He has extracted the maximum effort from all, at the same time promoting and fostering an excellent comradeship between flying personnel and ground staff thus instilling the team spirit so necessary to achieve success. He has instituted a fine spirit among his flying crews for accurate bombing and in obtaining photographs. On February 27th. 1942, he led the force of aircraft which carried the parachute troops who made the raid on Bruneval, thus again demonstrating his outstanding powers of leadership and organisation. By his courage, self-sacrifice and devotion to duty, this officer has set an example which, although attained by few, is admired by all." Second DSO awarded as a bar for on the ribbon of the first DSO.

- ↑ Acting Wing Commander, 161 Squadron, Royal Air Force. Citation reads: This officer has completed a very large number of operational missions and achieved much success. By his outstanding leadership, exceptional ability and fine fighting qualities, he has contributed in a large measure to the high standard of morale of the squadron he commands. Third DSO awarded as second bar for on the ribbon of the first DSO.

- ↑ The reader will note the wording in Pickard's third DSO is rather vague. Thus was due to the highly secret nature of the work 161 Squadron was conducting, which did not become known to the general public until the mid 1970s.

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fraser, Katie Battling for the honour of a wartime hero Daily Express 7 April 2004

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Times, 22 September 1944 (page 7 issue 49962)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Coxon, David (19 May 2016). "Brave Percy was the Wartime Pick of the RAF Bunch". Bognar Regis Observer. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Pickard, Percy Charles". World War 2 Awards. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Hamilton 1977, p. 22.

- ↑ "No. 34369". The London Gazette. 9 February 1937. p. 895.

- ↑ "No. 34457". The London Gazette. 23 November 1937. p. 7352.

- ↑ Hamilton 1977, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Orchard, Adrian Group Captain Percy Charles “Pick” Pickard DSO**, DFC 1915 - 1944 February 2006

- ↑ Bourne 2013, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Sedgwick, Philip (17 February 2017). "Leyburn RAF ace Alan Broadley died on mission to save others". Darlington and Stockton Times. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Raid on Amiens Prison – The Myth of the Mosquito". Britain at War Magazine. 1 February 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- 1 2 Barr Smith, Robert (12 January 2017). "Operation Jericho: Mosquito Raid on Amiens Prison". WWII. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (18 October 1941). ""Target for Tonight", a Fine Fact Film About the R.A.F., at the Globe -- Comedy at Central". New York Times. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Broadley, John Alan". World War 2 Awards. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Ward 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ "Bomber Command No. 51 Squadron". Royal Air Force. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ↑ Otway 1990, p. 67.

- ↑ Harclerode 2005, p. 210.

- ↑ "161 Squadron History". Royal Air Force. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ The Tempsford Memorial Trust

- ↑ O'Connor 2010, p. Chapter 3.

- ↑ O'Connor 2010, p. Chapter 6.

- ↑ McCairns 2015.

- ↑ Gunston, Bill. Classic World War II Aircraft Cutaways. London: Osprey, 1995. ISBN 1-85532-526-8.

- ↑ Hamilton 1977, p. 130.

- ↑ Hamilton 1977, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Hamilton 1977, p. 135.

- 1 2 Bowyer 2001, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Shaw, Martin (23 October 2011). "Operation Jericho". BBC. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Attack on Amiens prison, 18th February 1944". Royal Air Force. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ↑ "Strike on Gestapo prison at Amiens". Royal Australian Air Force, Air Power Development Centre. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ "Deaths". Issue 49962; col D. The Times. 22 September 1944. p. 7.

- ↑ Casualty details—Pickard, Percy Charles, Casualty details—Broadley, John Alan, Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved on 5 November 2008. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ↑ The Times, 19 February 1945

- Bibliography

- Bourne, Merfyn The Second World War in the air : the story of air combat in every theatre of World War Two Leicester: Matador, (2013).

- Bowyer, Chaz Bomber Barons Barnsley : Cooper, (2001).

- Bowyer, Chaz Mosquito at war London: Allan (1979). ISBN 978-0-7110-0474-0

- Hamilton, Alexander Wings of Night : Secret Missions of Group Captain Pickard, DSO and Two Bars, DFC Crecy Bks., (1977). ISBN 978-0-7183-0415-7

- Harclerode, Peter Wings Of War – Airborne Warfare 1918-1945 Weidenfeld & Nicolson (2005). ISBN 0-304-36730-3

- McCairns, James Lysander Pilot (2015).

- O'Connor, Bernard RAF Tempsford : Churchill's most secret airfield Stroud: Amberley (2010).

- Oliver, David Airborne Espionage Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing Limited (2005).

- Orchard, Adrian Group Captain Percy Charles “Pick” Pickard DSO**, DFC 1915 - 1944 February 2006

- Otway, T.B.H The Second World War 1939-1945 Army — Airborne Forces Imperial War Museum, (1990). ISBN 0-901627-57-7

- Verity, Hugh We Landed by Moonlight Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan Limited (1978).

- Ward, Chris and Steve Smith 3 Group Bomber Command: an operational record Barnsley : Pen & Sword Aviation (2008).

- Williams, Ray Armstrong Whitworth's Night Bomber Aeroplane Monthly, October 1982.

- Obituary: Royal Air Force Group Captain Percy Charles Pickard The Times, 22 September 1944.

External links

- Percy Charles Pickard

- Percy Charles Pickard at Find a Grave

- Group Captain Percy "Pick" Pickard pictured while resting from operations as Station Commander at RAF Lissett

- Official photographic record of Amiens prison raid