Charles Ball

| Charles Ball | |

|---|---|

Charles Ball wearing the uniform of the U.S. Navy's Chesapeake Bay Flotilla under the command of Commodore Joshua Barney in the War of 1812 | |

| Born |

1780 Calvert County, Maryland? |

| Died |

? ? |

| Occupation | slave, cook, sailor |

| Spouse(s) | 1 |

| Children | yes |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1800-1815 |

| Battles/wars |

|

Charles Ball (1780 - ?) was an enslaved African-American from Maryland, best known for his account as a fugitive slave, The Life and Adventures of Charles Ball (1837) and having served in the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla of the U.S. Navy under the command of Commodore Joshua Barney in the War of 1812.

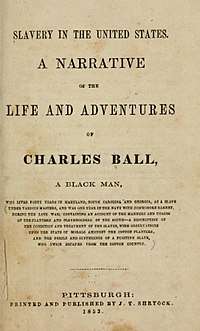

Autobiography

The main source for Ball's life is his autobiography, "Slavery in the United States: A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, a Black Man, Who Lived Forty Years in Maryland, South Carolina and Georgia, as a Slave Under Various Masters, and was One Year in the Navy with Commodore Barney, During the Late War.", published in 1837 with the help of Isaac Fisher. An 1846 re-edited version by Frances Catherine Barnard ,The Life of a Negro Slave, was published by Charles Muskett.[1] In 1859, an abridged edition of this autobiography appeared, called "Fifty Years in Chains, or, The Life of an American Slave." The 1859 edition only has 430 pages compared with the original 517. Some valuable parts have been omitted in 1859, such as the account of the religion of Ball's African grandfather and all references to Ball's participation in the War of 1812.

Page references in this article refer to the 1837 edition.

Charles Ball's memoir is an account of the life of slaves and slave-owners in the early 19th century. The book includes the stories of some other African Americans whom the author was acquainted to. So it is one of the few pieces of Western literature of that time giving a voice to the experience of Africans, including a description of religious customs in the part of Africa where Ball's grandfather grew up and an adventure with lions in the Sahara desert related by a young African.

Authenticity

Since there are no other sources for Ball's life, some scholars hold Ball's autobiography to be an invention by a white abolitionist.

African ancestry

According to Ball's autobiography, his grandfather was a man from a noble African family who was enslaved and brought to Calvert County, Maryland around 1730.

The 1837 edition dedicates three pages (Pages 22–24) to the description of his religion as the old man explained it to his young grandson. This description has some similarities with Islam, but there are also differences, so it is not clear, if his grandfather was Muslim or not. Other Africans whose religion Ball mentions, are explicitely called "Mohamedans" (p. 165).

The precepts of that religion are contained in a book a copy of which is kept in each house, implying that the grandfather's African society had a high degree of literacy, whereas Charles Ball is illiterate. This may be worth mentioning because contemporary apologetics of slavery often claimed that Africans had been "civilized" by slavery.[2]

Life in Slavery

Charles Ball was born as a slave in the same county around 1781. He was about four years old, when his owner died. To settle the debts, his mother, several brothers and sisters and he himself were sold to different buyers. His first childhood memory recorded in the book is his being brutally separated from his mother by her buyer: "Young as I was, the horrors of that day sank deeply into my heart, and even at this time, though half a century has elapsed, the terrors of the scene return with painful vividness upon my memory."[3]

By way of inheritance, sale and even as a result of a lawsuit, he is passed on to various slaveholders. From January 1, 1798 to January 1, 1800 he is hired out to serve as a cook on the frigate USS Congress. In 1800, he marries Judah. In 1805, when his eldest son is 4 years old, he is sold to a South Carolinian cotton planter, thus separated from his wife and children who had to remain in Maryland.

In September 1806, he is given as a present to the newly wedded daughter of his owner and has to relocate to Georgia to a new plantation. Shortly afterwards, after the sudden death of the new husband, the new plantation, together with the slaves, including him, is rent out to yet another slaveholder, with whom he builds up a relationship of mutual trust. He becomes the headman on the new plantation, but suffers from the hatred of his master's wife. In 1809, when his dying master is already too weak to interfere, he is cruelly whipped by that woman and her brother. After that, he plans his escape, which he puts into practice after his master's death. Travelling by night to avoid the patrols, using the stars and his obviously excellent memory for orientation, suffering terribly from hunger and cold, not daring to speak to anybody, he returns to his wife and children in early 1810.

War of 1812 Chesapeake Flotilla service

Charles Ball also served in the U.S. Navy during the War of 1812. In 1813, Ball had enlisted in Commodore Joshua Barney's Chesapeake Bay Flotilla and fought at the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814. An excerpt from his account of the battle, which was a resounding defeat for the Americans:

"I stood at my gun, until the Commodore was shot down, when he ordered us to retreat, as I was told by the officer who commanded our gun. If the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, could have been brought to charge the British, in close fight, as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time; but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs."[4]

Life after the War

In 1816, his wife Judah died. Ball married a second time, Lucy, and was able to buy a small farm from money he had earned and saved. In 1830, he is traced down by the man who whipped him 21 years earlier, kidnapped and again taken to Georgia. He escapes again to learn that Lucy and the children have been kidnapped into slavery and his farm been taken by a white man. Because he legally still is a slave, he is not able to claim his rights, but has to relocate to Pennsylvania where he wrote his 1837 memoir, with the help of the white lawyer Isaac Fisher.[5][6]

Nothing is known of his later fate, nor of that of his wife or children.

Chronology

The first exact date given in the narrative is Christmas 1805 (p. 268), the date of his first Christmas on the plantation in South Carolina (p. 269). Before Christmas 1805, the author sometimes mentions the month (without the year) or the duration of a certain period. On his way to South Caronlia he enters Virginia during the first days of May (p. 41). So we can conclude that he was sold away from his home and family in Maryland at the end of April or beginning of May, 1805. Before that he had belonged to a Mr Ballard for "almost three years" (p. 33), and before that "three years" (p. 30), starting on New Year's Day, to a Mr Gibson. His time with Gibson coincides with a lawsuit which went on for "more than two years" (p. 29). We also learn that he married "soon after" (p. 30) being sold to Gibson and that his eldest son was four years old when they were separated in April / May 1805 (p. 465). So we may conclude that "almost three years" plus "more than two years" or "three years" means "five years and four months", thus fixing his 2-year-service (p. 28) on the USS Congress for the period from January 1, 1798 to January 1, 1800.

Depiction of Slavery

Recalling the brutal conditions in slave life, he describes the heartache of having family members sold away—as his mother and father were, and as he was separated from his wife and children, taken south chained to a line of other slaves. We also learn of the horrific conditions on slave ships bound for the West. On this slave's journey, he recounts that 1/3 of the slaves on the ship died during the passage to Charleston, South Carolina.

In the autobiography, Ball presents himself (or is presented by the writer) as a kind of model slave, who is determined to save his master "obediently and faithfully" (p. 33), and is proud of the "good character, for industry, sobriety, and humility, which I had established in the neighbourhood" (p. 35). But still, he has to suffer horrible cruelties. As a boy of twelve he falls into the hands of a severe master who makes him work hard while at the same time exposing him to hunger and cold. He is forcefully separated from his wife and his children, without even being allowed to say goodbye to them. He is kept in chains day and night during a march of four weeks and five days (p. 76), not even being able to wash the clothes, so that the vermin becomes „extremely tormenting“ (p. 99). One day he is falsely accused of murder and without any investigation his master prepares to have him flayed (skinned) alive. His life is saved only by the coincidental arrival of a white witness of the crime. On another occasion he is whipped without any reason. These parts of the story show that it was impossible for a slave to avoid the most cruel sufferings even if he complied with all the demands of his oppressors.

He also relates his observations of the life of his fellow slaves, e.g. "one very old man, quite crooked with years and labour" (p. 88), being compelled to work although he is no longer able to keep up with the other ones who "had no clothes on him except the remains of an old shirt, which hung in tatters from his neck and arms". On another plantation, in winter, when the frost "was sometimes very heavy and sharp", shoes are distributed only to those who are employed in picking cotton. "This deprived of shoes, the children, and several old persons, whose eye-sight was not sufficiently clear, to enable them to pick cotton." (p. 270) Slaves have to work even while being shaken by fever (p. 207). It may be worthwhile contrasting this reality with proslavery politicians of the same period stating that the "old and infirm slave ... in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress" was better of than the "pauper in the (European) poorhouse" in his "forlorn and wretched condition".[7]

Several methods of torture are described in detail. On one occasion, he cites a fellow slave relating the discussion of the slaveholders on how "the greatest degree of pain could be inflicted on me, with the least danger of rendering me unable to work" (p. 116).

Slavery in Maryland compared to the Deep South

While relating the first time he is driven to the Deep South, Ball frequently compares his observations there with the customs of his native Maryland. His summarizes his observations: "The general features of slavery are the same everywhere; but the utmost rigour of the system is only to be met with on the cotton plantations of Carolina and Georgia, or in the rice fields which skirt the deep swamps and morasses of the southern rivers." (p. 56) The day of his arrival on the plantation in South Carolina, he sees all his "future life, one long, waste, barren desert, of cheerless, hopeless, lifeless slavery; to be varied only by the pangs of hunger and the stings of the lash." (p. 144) He observes that the slaves there are poorly fed, the children go naked, the adults in rags.

Honors

Ball is one of those depicted on the Battle of Bladesburg Memorial, at Bladensburg, Maryland.

References

- ↑ Ball, Charles (1846). Frances Catherine Barnard, ed. The Life of a Negro Slave (Public domain ed.). C. Muskett.

- ↑ E.g. John C. Calhoun's 1837 speech in the US Senate Slavery a Positive Good

- ↑ Slavery in the United States, Digital version of the first edition of the autobiography, 1837, pages 15-18

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-11-22. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- ↑ Charles Ball Archived March 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ White, Deborah G.; Bay, Mia; Martin, Waldo E., Jr. Freedom on My Mind. Bedford/St. Martins. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-312-64883-1.

- ↑ John C. Calhoun's 1837 speech in the US Senate Slavery a Positive Good

- Charles Ball. The Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, 1837.

External links

- American liberty and slavery in the Chesapeake: The paradox of Charles Ball - U.S. National Park Service

- Works by Charles Ball at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Ball at Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Ball at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Slavery in the United States: A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball. New York: Published by John S. Taylor, 1837.

- Fifty Years in Chains, or, The Life of an American Slave. New York: H. Dayton; Indianapolis, Ind.: Asher & Co., 1859.

- Africans in America, Part 3, Charles Ball's Narrative Contains a short extract together with an ever shorter introduction (which confuses Georgia and South Carolina)