Cathedral of Saint John the Divine

| Cathedral of Saint John the Divine | |

|---|---|

The Western facade, including the Rose Window | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Manhattan, New York City |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°48′13″N 73°57′41″W / 40.80361°N 73.96139°WCoordinates: 40°48′13″N 73°57′41″W / 40.80361°N 73.96139°W |

| Affiliation | Episcopal Church in the United States of America |

| District | Episcopal Diocese of New York |

| State | New York |

| Status | Active |

| Patron | John the Evangelist |

| Website | StJohnDivine.org |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Christopher Grant LaFarge and George Lewis Heins; Ralph Adams Cram |

| Architectural type | Cathedral |

| Architectural style | Romanesque Revival and Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | December 27, 1892 |

| Materials | Stone, granite, limestone |

The Cathedral of Saint John the Divine is the cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. It is located in New York City on Amsterdam Avenue between West 110th Street and 113th Street in Manhattan's Morningside Heights neighborhood.

Designed in 1888 and begun in 1892,[1] the cathedral has undergone radical stylistic changes and interruption of construction by the two World Wars. Originally designed in the Byzantine Revival-Romanesque Revival styles, the plan was changed after 1909 to a Gothic Revival design.[2][3] After a large fire destroyed part of the North Transept and the organ on December 18, 2001, the Cathedral was formally rededicated in November 2008 after the completion of extensive renovations to the Cathedral and its organ.[2] It remains unfinished, with construction and restoration a continuing process.[2][3] As a result, it is often nicknamed St. John the Unfinished.[4]

There is some dispute about whether this cathedral or Liverpool Cathedral is the world's largest Anglican cathedral and church.[5] It is also the fifth largest Christian church in the world.[2] The exterior covers 121,000 sq ft (11,200 m2), spanning a length of 601 ft (183.2 meters) and a width of 232 ft (70.7 meters). The interior height of the nave is 124 feet (37.8 meters).

The cathedral houses one of the nation's premier textile conservation laboratories to conserve the cathedral's textiles, including the Barberini tapestries to cartoons by Raphael. The laboratory also conserves tapestries, needlepoint, upholstery, costumes, and other textiles for its clients.[6]

History

Planning and construction

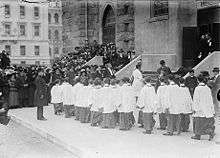

In 1887, Bishop Henry Codman Potter of the Episcopal Diocese of New York called for a cathedral to rival the Catholic St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan.[3] An 11.5-acre (4.7 ha) property, on which the Leake and Watts Orphan Asylum had stood, was purchased by deed for the cathedral in 1891.[7] After an open competition, a design by the New York firm of George Lewis Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge in a Byzantine-Romanesque style was accepted the next year.[3]

Construction on the cathedral was begun with the laying of the cornerstone on December 27, 1892, St. John's Day, when Bishop Henry Potter hit the stone three times with a mallet and said "Other foundation can no man lay, than that is laid which is Jesus Christ."[3] The foundations were completed at enormous expense, largely because bedrock was not struck until the excavation had reached 72 feet (22 m). The walls were built around eight massive 130-ton, 50-foot (15 m) granite columns, each turned as one piece,[8] sourced from Vinalhaven, Maine and said to be the largest in the world. The columns, which were transported to New York on a specially constructed barge towed by the large steam tug Clara Clarita, took more than a year to install.[9]

The first services were held in the crypt, under the crossing in 1899.[10] The Ardolino brothers from Torre Le Nocelle, Italy, did much of the stone carving work on the statues designed by the English sculptor John Angel. After the large central dome made of Guastavino tile was completed in 1909, the original Byzantine-Romanesque design was changed to a Gothic design.[3] Increasing friction after the premature death of Heins in 1907, fueled by a preference among some trustees for a less Romanesque and more Gothic style for the cathedral, ultimately led the trustees to dismiss the surviving architect, C. Grant LaFarge, and hire the noted Gothic Revival architect Ralph Adams Cram to design the nave and "Gothicize" what LaFarge had already built.[11] In 1911, the choir and the crossing were opened, and the foundation for Cram's nave began to be excavated in 1916.

J. Sanford Saltus, namesake of the American Numismatic Society's Saltus Award, presented Bishop William T. Manning with a life-size statue of Joan of Arc for the Cathedral's French Chapel, which was dedicated in January 1923.[12] The first stone of the nave was laid, and the west front was undertaken in 1925. Bishop Manning had announced a $10 million capital campaign to raise money for this project at a major press conference; the New York campaign committee, headed by Franklin D. Roosevelt, campaigned from 1923 to 1925 to raise US$6 million (equivalent to $86,000,000 in 2017).[13][14] Work at the church went on during the Great Depression as a result of monies raised in this campaign.

First opening

The Cathedral was opened end-to-end for the first time on November 30, 1941, a week before the bombing of Pearl Harbor.[2] Subsequently, construction on the cathedral was halted, because the then-bishop felt that the church's funds would better be spent on works of charity, and because the United States' subsequent involvement with the Second World War greatly limited available manpower. Although Cram intended to dismantle the dome and construct a massive Gothic tower in its place, this plan was never realized. The result is that the Cathedral reflects a mixture of architectural styles, with a Gothic nave, a Romanesque crossing under the dome; chapels in French, English and Spanish Gothic styles, as well as Norman and Byzantine; Gothic choir stalls, and Roman arches and columns separating the high altar and ambulatory.

The Very Reverend James Parks Morton, who became dean of the cathedral in 1972, fostered projects to enable it to become "a holy place for the whole city"[15] and encouraged a revival in the construction of the Cathedral. In 1979 the then bishop, the Right Reverend Paul Moore, Jr., decided that construction should be continued, in part to preserve the crafts of stonemasonry by training neighborhood youths, thus providing them with a valuable skill. In 1979, Mayor Ed Koch quipped during the dedication ceremony, "I am told that some of the great cathedrals took over five hundred years to build. But I would like to remind you that we are only in our first hundred years."

One architect who worked for Cram and Ferguson as a young man, John Thomas Doran, eventually became a full partner. (Cram and Ferguson became known as Hoyle, Doran and Berry. The firm exists today as HDB/ Cram and Ferguson). The November 1979 edition of LIFE magazine featured St. John the Divine Cathedral. To quote the magazine: (p. 102)

One architect from Cram's firm survives. At 80, John Doran is among the last architects able to draw Gothic plans - the difficult style is not taught in schools. He is helping St. John's new generation of builders. "Nothing I've done," Doran says, "has held my interest like the cathedral. Everything since then has just been making a living."

Construction on the south tower resumed for some years in the 1980s, during which campaign another 50 feet (15 m) of height was added,[3] in limestone rather than the granite of the original construction. Following the abandonment of this initiative, the scaffolding that had been erected around the south tower remained, rusting away (until it was removed in the summer of 2007).

Under master stone carvers Simon Verity and Jean Claude Marchionni, work on the statuary of the central portal of the Cathedral's western façade was completed in 1997. The Cathedral has since seen no further construction, and the new generation of trained stonecarvers has gone on to other projects.

21st century

In 2001 the choir parapet was completed with the addition of a sculpture by Chris Pelletierri of a group of four figures: Martin Luther King, Albert Einstein, Susan B. Anthony and Mohandas Gandhi.[16] The parapet was originally installed in 1922 with twenty niches for statues of the spiritual heroes of the twenty centuries since the birth of Christianity.[17] Representing the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries are statues of William Shakespeare, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. The niche for the 20th century was left blank until that century was completed.[18]

On the morning of December 18, 2001, a fire swept through the unfinished north transept,[2] destroying the gift shop and for a time threatening the sanctuary of the cathedral itself. It temporarily silenced the Aeolian-Skinner pipe organ. Although the organ was not damaged, all its pipes and other component parts had to be removed and laboriously cleaned and restored, to prevent damage from the fire's accumulated soot. Valuable tapestries and other items in the cathedral were damaged by the smoke.[2][19]

In January 2005, the cathedral began a major restoration, which was completed and the cathedral rededicated on Sunday, November 30, 2008.[2] A state-of-the-art chemical-based cleaning system was utilized, not only to remove smoke damage resulting from the 2001 fire but also the dark patina of 80 years of city air, filling the interior with unfamiliar light.[20]

In 2014, it housed one of the biggest pieces of sculpture ever displayed in the United States, Phoenix, by Chinese artist Xu Bing.[21]

Landmark status and property development on Cathedral grounds

In 2003, the cathedral was designated a landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; however, shortly thereafter, the designation was unanimously overturned by the New York City Council, some of whose members favored landmark status for the cathedral's entire footprint, rather than just the building. Councilman Bill Perkins proposed that the protective status should also be extended to the cathedral's grounds in order to control development there.[22] In 2017, the Cathedral and the grounds were designated a New York City Landmark.

In 2008, the cathedral leased the southeast corner of its property, which contained the Cathedral's playground and Rose Garden, to the AvalonBay Communities. A modern, glass apartment tower, the Avalon Morningside Park now occupies the space.[23]

A second residential building, the "Enclave", has been constructed on the northern edge of the Cathedral's property, along 113th St. Handel Architects designed the building for the Brodsky Organization, which has a 99-year lease on the land. The lease on the Enclave land pays the Cathedral about $3 million a year, the lease on the Avalon, about $2.5 million.[24]

Description

The cathedral is located at 1047 Amsterdam Avenue (between West 110th Street, also known as Cathedral Parkway, and 113th Street) in Manhattan's Morningside Heights. The cathedral's West Front entrance is in line with West 112th St. The New York Mount Sinai St. Luke's hospital and the campus of Columbia University are nearby.

The building as it appears today conforms primarily to a second design campaign from the prolific Gothic Revival architect Ralph Adams Cram of the Boston firm Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson. Without copying any one historical model, and without compromising its authentic stone-on-stone construction by using modern steel girders, Saint John the Divine is an example of the 13th century High Gothic style of northern France. The cathedral is 601 feet (183 m) in length, and the nave ceiling reaches 124 feet (38 m) high.[25] It is the longest Gothic nave in the United States, at 230 feet (70 m). At the west end of the nave, installed by stained glass artist Charles Connick[26] and constructed out of 10,000 pieces of glass, is the largest rose window in the U.S.[27] Seven chapels radiating from the ambulatory behind the choir are each in a distinctive nationalistic style, some of them borrowing from outside the Gothic vocabulary. These chapels are known as the "Chapels of the Tongues", and they are devoted to St. Ansgar, patron of Denmark, who is venerated as an apostle to the Scandinavian countries; St. Boniface, apostle of the Germans; St. Columba, patron of Ireland and Scotland; St. Savior (Holy Savior), devoted to immigrants from the east, especially Africa and Asia; St. Martin of Tours, patron of the French; St. Ambrose, patron of Milan; and St. James, patron of Spain. The designs of the chapels are meant to represent each of the seven most prominent ethnic groups to first immigrate to New York City upon the opening of Ellis Island in 1892, the same year the cathedral was begun.

In the center, just beyond the crossing, is the large, raised high altar, behind which is a wrought iron enclosure containing the Gothic style tomb of the man who originally conceived and founded the cathedral, the Right Reverend Horatio Potter, Bishop of New York. Later Episcopal bishops of New York, and other notables of the church, are entombed in side chapels.

Directly below this is a large hall in the basement, used regularly to feed the poor and homeless, and for meetings, and multiple crypts.

On the grounds of the cathedral, toward the south, are several buildings (including a synod hall and the Cathedral School of St. John the Divine), and a Biblical garden, as well as a large bronze work of public art by the cathedral's sculptor-in-residence, Greg Wyatt, known as the Peace Fountain, which has been both strongly praised and strongly criticized.

Great west doors

The great west doors on Amsterdam Avenue were designed between 1927 and 1931 by the designer Henry Wilson.[28] The bronze doors (unveiled as the "Golden Doors") were installed in 1936. The sequence of 48 relief panels presents scenes from the Old and New Testaments and the Apocalypse.

In his lifetime, Henry Wilson only produced four sets of bronze doors, St Mary's Church, Nottingham, the chapel at Welbeck Abbey, the Salada Tea Company in Boston, and these. The cathedral's great west doors were the last of the four commissions, and are on a monumental scale, measuring some 18 by 12 feet (5.5 m × 3.7 m). Henry Wilson died in Menton, France, in 1934, shortly after finishing the design but before the doors were installed.

Concerts and activities

The size of the cathedral's interior, the fourth largest in the world, presents a level of natural acoustics that confer a reverberation time in excess of eight seconds and an organic brilliance of tone. Music of many genres, including chant, choral music, organ music, and hymnody adapted for large cathedrals is therefore important for the worship regularly celebrated in its nave.

The cathedral is additionally a major center for concert musical performances in New York.[29] Organ recitals are held regularly Mondays at 1pm (free with price of general admission) and most Sundays at 5:15 pm, as well as on special occasions. In addition, several times a year on selected Sundays at 5:15 pm, the St. James's Recital Series features performances by local musicians, pianists in particular; recitals follow the 4:00 pm Choral Evensong in St. James Chapel and are free and open to the public.

The cathedral has an annual New Year's Eve Concert for Peace. The Postlude to Act I of Leonard Bernstein's opera Quiet Place received its New York premiere at the 1985 concert.[29] The 1990 concert was a tribute to Bernstein himself, who helped found the event and had died two months earlier on October 14.[30]

Duke Ellington's Second Sacred Concert, of his original sacred music compositions, premiered at the cathedral on January 19, 1968. No recording of the performance has surfaced to date. After its debut performance, the Second Sacred Concert was recorded on January 22 and February 19, 1968, at Fine Studio, New York City. The concert was originally issued as a double LP on Prestige Records. It was later reissued on a single CD without the original tracks "Don't Get Down On Your Knees To Pray Until You Have Forgiven Everyone" and "Father Forgive".[31] Performing at the recording session were Ellington on the piano and doing the narration, 16 of his orchestra members, four vocalists including the Swedish singer Alice Babs, and five choirs: the AME Mother Zion Church Choir, the choirs Of St Hilda's and St. Hugh's School, the Central Connecticut State College Singers, and the Frank Parker Singers.

In 1990, the avant-garde musician Diamanda Galas performed Plague Mass, a culmination of her work dedicated to the victims of the AIDS epidemic. Galas' performance consisted of covering her body in cattle blood and reinterpreting biblical texts and classic literature; she said it was a protest against what she saw as the ignorance and condemnation towards people with AIDS from religious and political groups.[32]

Paul Winter has given many concerts at the cathedral, and the Paul Winter Consort are the artists in residence.[33] Among the major musical event that takes place every year is a celebration of the feast day of Saint Francis of Assisi, when the Paul Winter Consort participates in a liturgical performance of Winter's Missa Gaia (Earth Mass). The musical group also performs at the annual Winter Solstice program. Musical performances and special events are customarily listed on the cathedral's website under Events & Programs. The Congregation of Saint Saviour, a separately incorporated congregation, makes its home at the cathedral. It offers events, classes and programs. curated by Fredericka Foster in

Art and Activism

In 2011The Value of Water,[34] the largest art exhibition to ever appear at the Cathedral,[35] featured over forty artists including Jenny Holzer, Robert Longo, Mark Rothko, William Kentridge, April Gornik and Bill Viola.[36][37] The exhibition, curated by artist activist Fredericka Foster, anchored a year long initiative on our dependence upon water.[38]

A statue exhibited during Holy Week of 1984, Edwina Sandys’ Christa, was part of a small exhibition on the feminine divine. Favorably received in general "but a particularly vocal minority condemned the piece and its placement in a house of worship through ecclesiastical denunciations and a plethora of hate mail that attacked the “blasphemy” of changing the symbol of Christ. These dissenters highlighted how the sculpture’s allegedly sexualized (i.e. female) figure brought attention to Christ’s human body, which was “blasphemous, shocking, and inappropriate.”"[39] The Christa Project: Manifesting Divine Bodies exhibition in 2016 brought back that statue,[40] "exploring the language, symbolism, art, and ritual associated with the historic concept of the Christ image and the divine as manifested in every person—across all genders, races, ethnicities, sexual orientations, and abilities.""[39][41]

Organ

The Great Organ was built by the Ernest M. Skinner in 1906 as the firm's Opus 150. It is the largest of five organs in the cathedral complex. It is located above the choir on the north and south sides. In 1954, it was enlarged by the Aeolian-Skinner Organ Company, Opus 150-A, under the tonal direction of G. Donald Harrison. During this rebuild, the State Trumpet was added and placed below the rose window.

Speaking on fifty inches (130 cm) of wind pressure, it is among the most powerful organ stops in the world. In late 2001, a fire in the north transept resulted in heavy smoke damage to the organ, which was finally returned to service in 2008. The Great Organ is currently valued at over eight million U.S. dollars.

Organists

- Walter Henry Hall 1905–1909

- Miles Farrow 1910–1931

- Norman Coke-Jephcott 1932–1953

- John Upham (interim) 1953–1954

- Alec Wyton 1954–1974[42]

- David Pizzaro 1974–1977

- Paul Halley 1977–1990

- Dorothy Papadakos 1990–2003

- Timothy Brumfield 2003–2008

- Bruce Neswick 2008–2011

- Kent Tritle 2011–present

Deans

- William Mercer Grosvenor, 1911–1916

- Howard Chandler Robbins, 1917–1929

- Milo Hudson Gates, 1930–1939

- James Pernette DeWolfe, 1940–1942

- James Albert Pike, 1952–1958

- John Vernon Butler, 1960–1966

- James Parks Morton, 1972–1997

- Harry Houghton Pritchett Jr., 1997–2001

- James August Kowalski, 2002–2017

- Clifton Daniel III, 2018–present

Notable funerals

- James Baldwin, writer, activist

- Dave Dellinger, activist

- John Gregory Dunne, novelist, screenwriter and literary critic

- Ethyl Eichelberger, theatrical artist

- James Gandolfini, actor

- Jim Henson, Muppets creator

- Richard Hunt, Muppet performer

- Robert Joffrey, choreographer

- Madeleine L'Engle, author

- Audre Lorde, poet, activist

- Paul Moore, Jr., bishop

- Nikola Tesla, inventor

- Terrence Tolbert, public service

- Duke Ellington, composer

- John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie, October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer

- Memorial Service for Eleanor Roosevelt,[43] activist, diplomat, U.S. First Lady

Gallery

- Statues of saints

Western entrance on Amsterdam Avenue

Western entrance on Amsterdam Avenue Scaffolding covering the south tower in 2005

Scaffolding covering the south tower in 2005- Aerial view of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine and surrounding grounds and neighborhood (2010)

- Cathedral and Peace Fountain

.jpg) Partial exterior view of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine (2010)

Partial exterior view of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine (2010).jpg) Figures of saints carved into exterior columns 1 (2010)

Figures of saints carved into exterior columns 1 (2010).jpg) Figures of saints carved into exterior columns 2 (2010)

Figures of saints carved into exterior columns 2 (2010).jpg) Figures carved into exterior columns, detail (2010)

Figures carved into exterior columns, detail (2010).jpg) Figures carved into exterior columns, detail, closeup view (2010)

Figures carved into exterior columns, detail, closeup view (2010).jpg) Western entrance, detail (2010)

Western entrance, detail (2010).jpg) Stained glass window within the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine (2010)

Stained glass window within the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine (2010)

See also

References

- ↑ "Cathedral of Saint John the Divine - New York Architecture". New York Architecture. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Chan, Sewell (November 30, 2008). "Repaired After Fire, Cathedral Reopens". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

Seven years after a raging fire destroyed its north transept and crippled its organ, the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine was rededicated on Sunday morning in a service attended by religious leaders, political leaders and thousands of New Yorkers.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kirby, David (January 10, 1999). "St. John The Unfinished. Dean of Cathedral on Morningside". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, more than a century in the making, may never be really finished. ...

- ↑ Peter W. Williams, Houses of God: Region, Religion, and Architecture in the United States, University of Illinois Press, 2000, p. 68, ISBN 978-0252069178 Guinness Book of World Records, 1990 p. 267; William R. Hutchison, "Houses of God", Church History 67.4 (December 1998), pp. 807-809.; "St. John the Unfinished", National Review, February 24, 1997; "Annals of St. John the Unfinished", The New York Times, November 20, 1994.

- ↑ The title depends on which dimensions are counted. For a discussion on the matter of size, see Quirk, Howard E., The Living Cathedral: St. John the Divine: A History and Guide (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Co., 1993), p. 15-16. ISBN 978-0824512378

- ↑ "Textile Conservation Laboratory". The Cathedral of St. John the Devine. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ↑ Hall, Edward Hagaman, Guide to the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, page 25, The Laymen's Club, 1920

- ↑ "Philadelphia Roll & Machine Works". Vintage machinery. April 27, 2012.

- ↑ Rich Hewitt: "Church's columns quarried on Vinalhaven", Bangor Daily News, December 19, 2001.

- ↑ "History". Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ↑ LaFarge, John, S.J. The Manner Is Ordinary. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1954, pp. 389-91.

- ↑ "J. Sanford Saltus Obituary" The Numismatist v. 35, n. 8; August 1922, p. 379 via Google Books retrieved January 4, 2017

- ↑ "Letter from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Dr. Charles D. Walcott", Proceedings of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution at the Annual Meeting held December 11, 1924, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, November 18, 1924, pp. 639–40

- ↑ Meyer Berger, "Lady Bishop", in Ruth Adler, editor, The Working Press: Special to The New York Times, New York: Ayer Publishing, 1981, pp. 155-60; accessed April 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Religion: A People's Cathedral". TIME. July 16, 1973. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ Lazarowitz, Elizabeth (March 25, 2011). "Morningside Heights-raised sculptor Chris Pelletierri carves niche despite economy". New York Daily News.

- ↑ "Nineteen Statues Represent Foremost Workers for World Uplift Since Christ" (PDF). The New York Times. July 15, 1922.

- ↑ "A Christian Hall of Fame". The Literary Digest. 74 (5): 32–34. July 29, 1922.

- ↑ "Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine". Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ↑ Vitello, Paul (November 30, 2008). "Awash in New Light, Angels Are Revealed". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, the mother church of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, and one of the city’s premier architectural monuments, was rededicated on Sunday, seven years after a smoky fire blackened its vast interior and decommissioned its 8,500-pipe organ.

- ↑ Vogel, Carol (February 14, 2014). "Phoenixes Rise in China and Float in New York". The New York Times.

- ↑ Winnie Hu (October 25, 2003). "No Landmark Status for St. John the Divine". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine has punctuated the New York skyline for more than a century, but its designation as an official city landmark was rejected yesterday by the City Council.

- ↑ C. J. Hughes (September 5, 2008). "Worldly, Meet Other-Worldly". The New York Times.

- ↑ McKeogh, Tim (20 November 2016). "New Rentals Steps From St. John the Divine". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine". New York Architecture. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Chronology of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine" (PDF). Stjohndivine.org. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York City". Sacred Destinations. July 26, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ↑ Manton, Cyndy. Henry Wilson: Practical Idealist, The Lutterworth Press (2009), ISBN 978-0-7188-3097-7.

- 1 2 "Music: Peace concert at St. John the Divine", The New York Times, January 2, 1986; Retrieved November 18, 2011

- ↑ "New Year's News", Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1990; Retrieved November 18, 2011

- ↑ A Duke Ellington Panorama accessed May 17, 2010

- ↑ "Critic's Choice". The New York Times, reproduced at diamandagalas.com. October 12, 1990. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Paul Winter". Paul Winter.

- ↑ Bukauskas, Dovilas. "The Value of Water". worldpolicy.org. World Policy Institute. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ↑ Miller, Reverend Canon, Tom. "The Value of Water Exhibition". UCLA Art Science Center. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ Escobedo Shepherd, Julianne (September 30, 2011). "10 Must-See Artists at "The Value of Water," a Conversationist Art Show in New York". AlterNet.org. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ↑ Cotter, Mary. "Manhattan Cathedral Examines "The Value of Water" in a New Star-Studded Art Exhibition". inhabitat.com. inhabitat. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ Rev. Dr. A. Kowalski, James. "The Cathedral of St. John the Divine and The Value of Water". huffingtonpost.com. Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- 1 2 "The Christa Project: Manifesting Divine Bodies". stjohndivine.org. St. John the Divine Catherdral. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ↑ Barron, James (October 4, 2016). "An 'Evolving' Episcopal Church Invites Back a Controversial Sculpture". New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ↑ Frank, Priscilla (October 6, 2016). "30 Years Later, A Sculpture Of Jesus As A Nude Woman Finally Gets Its Due". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ↑ Whitney, Craig R. (March 23, 2007). "Alec Wyton, 85, Organist Who Updated Church Music, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ↑ Peyser, Marc. "Eleanor Roosevelt's Anything-but-Private Funeral". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. |

- Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine official website

- Congregation of Saint Saviour at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine official website

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, "Designation List 347" (2003)

- Article on the cathedral's architecture

- Article on the cathedral's history

- Article on the specifications of the Great Organ