Cathedral of Idanha-a-Velha

| Cathedral of Idanha-a-Velha (Catedral de Idanha-a-Velha) | |

| Cathedral (Catedral) | |

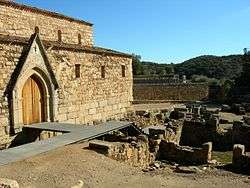

The Romanesque cathedral of Idanha-a-Velha as seen from the cemetery | |

| Official name: Catedral de Idanha-a-Velha | |

| Named for: Idanha-a-Velha | |

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Region | Centro |

| Subregion | Beira Interior Sul |

| District | Castelo Branco |

| Municipality | Idanha-a-Nova |

| Location | Monsanto e Idanha-a-Velha |

| - coordinates | 39°59′46.7″N 7°8′40.6″W / 39.996306°N 7.144611°WCoordinates: 39°59′46.7″N 7°8′40.6″W / 39.996306°N 7.144611°W |

| Styles | Visigoth, Islamic, Romanesque, Gothic, Manueline |

| Materials | Granite, Schist, Marble, Limestone, Masonry, Tile |

| Origin | 4th century |

| - Initiated | 585 |

| Owner | Portuguese Republic |

| For public | Public |

| Easiest access | Rua da Sé |

| Management | Instituto Gestão do Patrimonio Arquitectónico e Arqueológico |

| Operator | DRC (Regulatory decree 34/2007 (29 March 2007) |

| Status | Property of Public Interest Imóvel de Interesse Público |

| Listing | Decree 40/684, Diário do Governo 146 (13 July 1956); Included in the Special Protection Zone (ZEP) of architectural and archaeological group of Idanha-a-Velha (PT020505040022)[1] |

| Wikimedia Commons: Catedral de Idanha-a-Velha | |

The Former Cathedral of Idanha-a-Velha (Portuguese: Catedral de Idanha-a-Velha) is a medieval the decommissioned Catholic cathedral of the former bishopric of Egitânia, in the Freguesia (civil parish) of Monsanto e Idanha-a-Velha, in the municipality of Idanha-a-Nova, in the central Portuguese district of Castelo Branco.

History

A primitive basilica (Roman church) was constructed sometime in the 4th century. Influenced by this decision, King Theodemar (Theodemer) of the Suebic Kingdom of Galicia (+570) created the Diocese of Egitânia in 559-569.[2][3] Around 585, the cathedral started to be constructed, that included not only the main structure by the baptistery and the hypothetical palace.[3] In 715 however, the diocese was suppressed (possibly with an apostolic succession of errant bishops), due to the Moorish invasion of Iberia, rendering the church's cathedral function void.

Between the 9th and 10th century, during the Moorish occupation, the temple was transformed into a mosque.[3]

Following the Reconquista (sometime between the 12th and 13th century), a new chapel was erected, re-using the materials from the previous construction.[3] Gualdim Pais, Master of the Knights Templar was donated the region of Idanha-a-Velha by D. Afonso Henriques in 1165.[3] Thirty years later (1197) the region was donated to Lopo Fernandes, then Templar Master in Portugal, who two years later saw the transference of the 'revived' episcopal seat to Guarda, diminishing Idanha's importance,[3] when the bishopric was nominally 'restored' in 1199 but (re)named after its new see as Diocese of Guarda, which built its own cathedral and abandoned the Egitânia title, without awarding Co-cathedral status (like the former Cathedral of Pinhel, another former bishopric).

In 1229, Master Vicente, then Bishop Guarda, received the donation of the couto (legally immune zone) of Idanha, but Marim Martins became the new master in 1244.[3]

In 1326, the Templar Knights received 500 pounds from the Commander of Rio Frio, for the "spiritual" benefit and temporal needs of the local population.[3] In addition, 100 libras was received from the commanderies of Almourol and Cardiga and 100 for the "spiritual" needs of Proença.[3]

Work to renovate the old cathedral were initiated in 1497 by King D. Manuel, who added an additional 5 réis annually for its maintenance.[3] Part of the monies went to the construction of new doorway.[3]

But, by the 16th century, the church was found partially buried, and work was initiated to recuperate the site, resulting in the correction of the orientation of presbytery.[3] On 10 October 1505, D. João Pereira and Father Francisco, extended the commandery following the death of Father Garcia Afonso, during a state visit.[3] The visitors described a church as including three naves, with seven arches on the right and four on the left, along with two entrance-way (one to the north and smaller to the south). The entrance-way was constructed of sculpted stone, and protected by awning supported by stone columns and covered in tile.[3] Over the principal portico was a stone belfry with two bells and decorated with a weather vane, while to the left of the awning was a building with five arches. The presbytery included vaulted ceiling in granite, with altar over column under a sculpted imagery of the Virgin Mary.[3] There were lateral altars dedicated to Santo António and São Sebastião, with painted sculptures, in addition to images of Santa Catarina and São Sebastião.[3]

On 10 October 1537, Father António Lisboa visited the site and noted that there was an exterior doorway with awning, supported by five columns, 6 varas high.[3] The chapel had 4 varas length and 4 wide, covered in azulejo tile, that included an old retable with a painting of the Virgin Mary, surmounted by red twill canopy.[3] Alongside the chapel they constructed a sacristy, with collateral altars and painted wood. To the left of the portico was a baptismal fountain.[3]

In 1589, the Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Rosário functioned from the site, and by 1593, a new portico was opened on the south facade.[3]

In the 19th century, the church was transformed into a local cemetery, as a result losing it cultural role.[3]

The first archaeological prospecting began in 1955, under the responsibility of Fernando de Almeida, the artifacts extract were dispersed throughout various museums and particular collections (Museum Lapidar Igeditano de António Marrocos, Museum Francisco Tavares Proença Júnior, National Museum of Archaeology).[3] In 1960, under the same direction, new archaeological excavations were undertaken in the interior, resulting in the lowering of the pavement and consolidation of the structure.[3] The DGEMN began a plan to construct a new cover in 1962, that was implemented in 1964-1965, financed by Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.[3] Restoration on site began in 1964, with the consolidation of walls, reconstruction of the facade, leveling of the lateral walls, construction of the roofing and opening of the window over the principal door.[3] A new phase of restoration occurred between 1969 and 1971, supplemented in 1986 by work to benefit the cathedral and baptistry.[3]

Between 1987 and 1988, under the direction of Artur Corte Real, there were emergency interventions in the necropolis.[3] The following year, in a joint operation by IPPC and DGEMN, the cover the baptistery, fence and pedestrian accesses were unproved.[3]

The site was ceded to the IPPAR Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico (Portuguese Institute of Architectural Patrimony) on 12 February 1998.[3] The IPPAR initiated work to improve the site, that lasted until 2006, that included a metallic structure around the baptistery and erection of glass to protect some parts of the site.[3] As part of the Plano de Aldeia of the Aldeias Históricas de Portugal (Beira Interior), interventions on the property were initiated under architect Alexandre Costa by the IPPAR.

Architecture

The cathedral lies in a fortified settlement situated on the right margin of the River Ponsul,[4] implanted in the lowlands south of Monsanto. The church is situated within the walls, alongside the gate south of the wall.

The cathedral has a rectangular plan with two orthogonal axis, comprising a principal rectangle which juxtapositions a larger rectangular space on its largest side. The principal facade is oriented to the northeast, two stories tall with an arched doorway with rectangular lintel, secondary circular oculus and belfry. Its southwest facade includes two doors with rectangular lintels on the first floor and simple window on the second register. In the northwest, the doorway is surmounted by decorated gablette flanked by four gaps. On the superior register, corresponding to the clerestory of the central nave, with seven-arched openings. On the southeast, is a window with straight lintel and two slits, integrating an apparatus and Roman inscription, while on the second register there are five arches. There are two exterior baptisteries, one on the south entrance and another next to the principal facade. The exterior baptistery, in a cruciform plan, includes smaller adjacent tanks. A cistern is addorsed to the church, left of the principal portico.

Interior

The three nave plan (one of which was truncated) has wood flooring and slabs of granite, with access staircase in rose marble. The central nave is longer and wider than the lateral lengths, separated by arches, on columns and pilasters. Walls on the southeast and northeast have arcades of masonry, while the northeast have arches over decorated marble. The entire space is covered in wood ceiling. The southeast lateral chapel is rectangular and covered in vaulted ceiling, with a mural painting that represents St. Bartholomew with the devil at his feet (in ochres and burnt sienna) and decorative flourishes (in grey). Covered in shell-type covering, the chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary, integrates the upper part of the wall, dating to 1593, and is decorated with geometric, zoomorphic, cruciform and angel heads. There are also vestiges of a mural painting between the two chapels, that represents Calvário, Cruz de Cristo and Santo António.

References

- ↑ Classified as part of a group with the bridge over the Rio Ponsul (PT0505040081)

- ↑ In 569, the Bishop of Egitânea was present at the Council of Lugo, confirming the existence of the bishopric.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Conceição, Margarida; Costa, Marisa (2001), SIPA, ed., Catedral de Idanha-a-Velha (IPA.00005882/PT020505040010) (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico, archived from the original on 13 March 2016, retrieved 1 December 2016

- ↑ The river's name was a toponymy derived from the termo Procônsul

Sources

- "A nova envolvência da Sé de Idanha-a-Velha - a inauguração é amanhã", Gazeta do Interior (in Portuguese), 15 February 2006

- Almeida, Fernando de (1956), Egitânia, História e Arqueologia (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Almeida, Fernando de (1957), "Notas sobre as Primeiras Escavações em Idanha-a-Velha", Separata das Actas do XXIII Congresso luso-espanhol (in Portuguese), Coimbra, Portugal

- Almeida, Fernando de (1962), Arte Visigótica em Portugal (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa

- Almeida, Fernando de (1977), Ruínas de Idanha-a-Velha, Civitas Igaeditanorum. Egitânea - guia para o visitante (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Almeida, Fernando de; Ferreira, Octávio da Veiga (1965), "O baptistério paleocristão de Idanha-a-Velha (Portugal)", Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueologia (in Portuguese), XXXI, Valladolid, Spain, pp. 134–136

- Arte Visigoda em Portugal (in Portuguese), Porto, Portugal: Catálogo de exposição, 1955

- Barroca, Mário (1990), "Contribuição para o estudo dos testemunhos pré-românicos de Entre-Douro-e-Minho", IX Centenário da Dedicação da Sé de Braga (in Portuguese), I, Braga, Portugal, pp. 101–145

- CALADO, Maria (1988), Idanha-a-Velha. Memória histórica e património cultural. Idanha-a-Velha (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal, pp. 11–16

- Castelo-Branco, Manuel da Silva (1976), "A Sé egitaniense na Era Quinhentista", Estudos de Castelo Branco (in Portuguese), Castelo, Portugal, pp. 46–53

- Correia, Vergílio (10 October 1938), "Lembrança de Idanha-a-Velha", Diário de Coimbra (in Portuguese) (IX, 2727), Coimbra, Portugal, p. 1

- Correia, Vergílio (1945), "Idanha-a-Velha", Mvsev (in Portuguese), IV (9), Porto, Portugal, pp. 106–120

- Corte-Real, Artur; Policarpo, Isabel (1996), Idanha-a-Velha, Processo de Classificação (in Portuguese), Coimbra, Portugal

- Fernandes, A. de Almeida (1968), Paróquias suevas e dioceses visigóticas (in Portuguese), Viana do Castelo, Portugal

- Fernandes, Paulo Almeida (2006), "Antes e depois da Arqueologia da Arquitectura: um novo ciclo na investigação da mesquita-catedral de Idanha-a-Velha", ARTIS (in Portuguese) (5), Lisbon, Portugal: Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Letras de Lisboa, pp. 49–72

- Fernandes, Paulo Almeida (2000), "O primeiro restauro da Mesquita-Catedral de Idanha-a-Velha, a propósito de uma nota inédita de Fernando de Almeida", Revista Raia (in Portuguese) (21), Castelo Branco, Portugal, pp. 42–47

- Ferreira, Seomara da Veiga; Costa, Maria da Graça Amaral da (1970), Etnografia de Idanha-a-Velha (in Portuguese), Castelo, Portugal

- Ferro, Maria José Pimenta (1971), As doações de D. Manuel, Duque de Beja a algumas igrejas da Ordem de Cristo (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Fonseca, Crispiano da (1927), A Aegitanea - Idanha-a-Velha (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Gonçalves, Catarina Valença (2001), A Pintura Mural em Portugal: os casos da Igreja de Santiago de Belmonte e da Capela do Espírito Santo de Maçainhas (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa

- Hormigo, José Joaquim M (1981), Visitações da Ordem de Cristo em 1505 e 1537 (in Portuguese), Amadora, Portugal

- Landeiro, José Manuel (1952), Da Velha Egitânia (in Portuguese), 1/2 (11), Beira Alta, Portugal, pp. 3–18

- Lopes, F. de Pina (1951), A Egitânia Através dos Tempos (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Marcelos, M. Lopes (1993), Beira Baixa - Novos Guias de Portugal (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Marrocos, A. Manzarra (1936), Idanha-a-Velha: Estudo Antropogeográfico (in Portuguese), Famalicão, Portugal

- Mattos, Armando de (1947), "A basílica de Idanha-a-Velha", Douro Litoral (in Portuguese) (7) (Série 1 ed.), pp. 32–33

- Neves, Vítor Pereira (3 July 1992), "Importante achado arqueológico", Reconquista (in Portuguese), p. 17

- Neves, Vítor Pereira (25 September 1992), "Futuro da Egitânia garantido", Reconquista (in Portuguese), p. 19

- Neves, Vítor Pereira (1996), As Aldeias Históricas de Monsanto, Idanha-a-Velha e Castelo Novo (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico Classificado, Inventário. Distrito de Castelo Branco (in Portuguese), I, Lisbon, Portugal: IPPAR Instituto Português do Património Arquitetónico, 1993

- Pereira, Félix Alves (1909), "Estudos Igeditanos", O Archeologo Portuguez (in Portuguese), XIV, Lisbon, Portugal

- Pimenta, Alfredo (1944), "Alguns documentos para a História de Idanha-a-Velha", Subsídios para a História Regional da Beira Baixa (in Portuguese), I, Castelo, Portugal, pp. 133–198

- Proença, Júnior; Tavares, Francisco (1910), Archeologia do Distrito de Castelo Branco (in Portuguese), Leiria, Portugal

- Real, Manuel Luís (1995), "Inovação e resistência: dados recentes sobre a antiguidade tardia no Ocidente peninsular", IV Reunião de Arqueologia Cristã Hispânica (in Portuguese), Barcelona, Portugal

- Salvado, Pedro (1987), "Idanha-a-Velha: das «ruínas de ruínas» a que futuro?", O estudo da História, 1986-1987 (in Portuguese), 2 (Série 2 ed.), pp. 93–96

- Salvado, Pedro (1988), Elementos para a cronologia e para a bibliografia de Idanha-a-Velha (in Portuguese), Idanha-a-Velha, Portugal

- Silva, Pedro Rego da (1998), "Memórias Paroquiais - Idanha-a-Velha (1758)", A Raia (in Portuguese) (6) (Jullho-Agosto ed.), pp. 20–25

- Torres, Cláudio (1992), "A Sé - Catedral da Idanha", Arqueologia Medieval (in Portuguese), 1, Porto, Portugal, pp. 169–178

- Torres, Cláudio (1999), "Idanha-a-Velha - Sé-Catedral, antiga mesquita", Terras da Moura Encantada (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal, p. 68

- Torres, Cláudio; Macías, Santiago (1998), O legado Islâmico em Portugal (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Velho, Martim (1979), O Arrasamento da Idanha em 1133. Estudos de Castelo Branco (in Portuguese) (5), Castelo, Portugal, pp. 45–47