Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958 film)

| Cat on a Hot Tin Roof | |

|---|---|

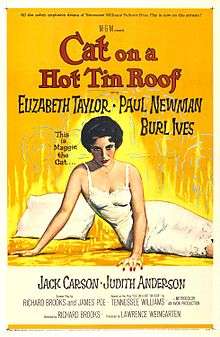

Theatrical release poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | Richard Brooks |

| Produced by | Lawrence Weingarten |

| Screenplay by |

Richard Brooks James Poe |

| Based on |

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams |

| Starring |

Elizabeth Taylor Paul Newman Burl Ives Judith Anderson |

| Music by | Charles Wolcott |

| Cinematography | William Daniels |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.3 million[2] |

| Box office | $11.28 million[2] |

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is a 1958 American drama film directed by Richard Brooks.[3][4] It is based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning play of the same name by Tennessee Williams and adapted by Richard Brooks and James Poe. One of the top-ten box office hits of 1958, the film stars Elizabeth Taylor, Paul Newman, and Burl Ives.

Plot

Late one night, a drunken Brick Pollitt (Paul Newman) is out trying to recapture his glory days of high school sports by leaping hurdles on a track field, dreaming about his moments as a youthful athlete. Unexpectedly, he falls and breaks his leg, leaving him dependent on a crutch. Brick, along with his wife, Maggie "the Cat" (Elizabeth Taylor), are seen the next day visiting his family's estate in eastern Mississippi, there to celebrate Big Daddy's (Burl Ives) 65th birthday.

Depressed, Brick has spent the last few years drinking, while resisting the affections of his wife, who taunts him about the inheritance of Big Daddy's wealth. This has resulted in an obviously tempestuous marriage—there are speculations as to why Maggie does not yet have a child while Brick's brother Gooper (Jack Carson) and his wife Mae (Madeleine Sherwood) have a whole pack of children.

Big Daddy and Big Mama (Judith Anderson) arrive home from the hospital via their private airplane and are greeted by Gooper and his wife—and all their kids—along with Maggie. Despite the efforts of Mae, Gooper and their kids to draw his attention to them, Big Daddy has eyes only for Maggie. The news is that Big Daddy is not dying from cancer. However, the doctor later meets privately with first Gooper and then Brick where he divulges that it is a deception. Big Daddy has inoperable cancer and will likely be dead within a year, and the truth is being kept from him. Brick later confides in Maggie with the truth about Big Daddy's health, and she is heartbroken. Maggie wants Brick to take an interest in his father—for both selfish and unselfish reasons, but Brick stubbornly refuses.

As the party winds down for the night, Big Daddy meets with Brick in his room and reveals that he is fed up with his alcoholic son's behavior, demanding to know why he is so stubborn. At one point Maggie joins them and reveals what happened a few years ago on the night Brick's best friend and football teammate Skipper committed suicide. Maggie was jealous of Skipper because he had more of Brick's time, and says that Skip was lost without Brick at his side. She decided to ruin their relationship "by any means necessary", intending to seduce Skipper and put the lie to his loyalty to her husband. However, Maggie ran away without completing the plan. Brick had blamed Maggie for Skipper's death, but actually blames himself for not helping Skipper when he repeatedly phoned Brick in a hysterical state.

After an argument, Brick lets it slip that Big Daddy will die from cancer and that this birthday will be his last. Shaken, Big Daddy retreats to the basement. Meanwhile, Gooper, who is a lawyer, and his wife argue with Big Mama about the family's cotton business and Big Daddy's will. Brick descends into the basement, a labyrinth of antiques and family possessions hidden away. He and Big Daddy confront each other before a large cut-out of Brick in his glory days as an athlete, and ultimately reach a reconciliation of sorts.

The rest of the family begins to crumble under pressure, with Big Mama stepping up as a strong figure. Maggie says that she'd like to give Big Daddy her birthday present: the announcement of her being pregnant. After the jealous Mae calls Maggie a liar, Big Daddy and Brick defend her, even though Brick knows the statement is untrue and Big Daddy thinks the statement may be untrue. Even Gooper finds himself admitting, "That girl's got life in her, alright." Maggie and Brick reconcile, and the two kiss, with the implication that they will possibly make Maggie's "lie" become "truth".

Cast

- Elizabeth Taylor as Maggie "the Cat" Pollitt

- Paul Newman as Brick Pollitt

- Burl Ives as Harvey "Big Daddy" Pollitt

- Judith Anderson as Ida "Big Mama" Pollitt

- Jack Carson as Cooper "Gooper" Pollitt

- Madeleine Sherwood as Mae Flynn "Sister Woman" Pollitt

- Larry Gates as Dr. Baugh

- Vaughn Taylor as Deacon Davis

Production notes

The original stage production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof opened on Broadway March 24, 1955, with Ives and Sherwood in the roles they subsequently played in the movie. Ben Gazzara played Brick in the stage production and rejected the film role as did Elvis Presley. Athlete turned film star Floyd Simmons also tested for the role.[5]

Lana Turner[6] and Grace Kelly[7] were both considered for the part of Maggie before the role went to Taylor.

Production began on March 12, 1958, and by March 19, Taylor had contracted a virus which kept her off the shoot. On March 21, she canceled plans to fly with her husband Mike Todd to New York, where he was to be honored the following day by the New York Friars' Club. The plane crashed, and all passengers, including Todd, were killed. Beset with grief, Taylor remained off the film until April 14, 1958, at which time she returned to the set in a much thinner and weaker condition.[8]

Music and soundtrack

The music score, "Love Theme from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," was composed by Charles Wolcott in 1958. He was an accomplished music composer, having worked for Paul Whiteman, Benny Goodman, Rudy Vallee and George Burns and Gracie Allen. From 1934 to 1944, he worked at Walt Disney Studios. In 1950, he transferred to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios where he became the general music director and composed the theme for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The remaining songs on the soundtrack are composed by a variety of artists such as Andre Previn, Daniel Decatur Emmett and Ludwig van Beethoven.

Song list

- "Lost in a Summer Night" by André Previn and Milton Raskin

- "Nice Layout" by André Previn

- "Love Theme from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof" by Charles Wolcott

- "Dixie" by Daniel Decatur Emmett, played by the children on various instruments

- "Skina Marinka", adapted by Marguerite Lamkin, sung by the children

- "I'll Be a Sunbeam" by E.O. Excell, sung by the children

- "Boom, Boom and It Makes Me Crazy", adapted by Marguerite Lamkin, sung by the children

- "Kermit Returns" by André Previn

- "Fourth Movement, Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67" by Ludwig van Beethoven, played on a radio

- "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow", traditional, sung by the family

- "Some Folks" by Stephen Foster, played on a phonograph

- "Soothe My Lonely Heart" by Jeff Alexander

Reception

Tennessee Williams was reportedly unhappy with the screenplay, which removed almost all of the homosexual themes and revised the third act section to include a lengthy scene of reconciliation between Brick and Big Daddy. Paul Newman, the film's star, had also stated his disappointment with the adaptation. The Hays Code limited Brick's portrayal of sexual desire for Skipper, and diminished the original play's critique of homophobia and sexism. Williams so disliked the toned-down film adaptation of his play that he told people in the queue, "This movie will set the industry back 50 years. Go home!"[9]

Despite this, the film was highly acclaimed by critics. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that although "Mr. Williams' original stage play has been altered considerably, especially in offering explanation of why the son is as he is," he still found the film "a ferocious and fascinating show," and deemed Newman's performance "an ingratiating picture of a tortured and tested young man" and Taylor "terrific."[10] Variety called the picture "a powerful, well-seasoned film produced within the bounds of good, if 'adults only,' taste ... Newman again proves to be one of the finest actors in films, playing cynical underacting against highly developed action."[11] Harrison's Reports declared it "an intense adult drama, superbly acted by a formidable cast."[12] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post wrote, "'Cat on a Hot Tin Roof' has been transposed to the screen with almost astonishing skill ... Paul Newman does his finest work in the rich role of Brick, catching that remarkable fact of film acting—the illusion of the first time. It's a superlative performance and he's bound to be nominated for an Oscar."[13] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times declared, "It was a powerful stage drama and it is a powerful screen drama, and Brooks has exacted—and extracted—stunningly real and varied performances from his players ... You may not like it but you won't forget it readily."[14]

Not all reviews were as positive. John McCarten of The New Yorker wrote of the characters that "although it is interesting for a while to listen to them letting off emotional steam, their caterwauling (boosted Lord knows how many decibels by stereophonic sound) eventually becomes severely monotonous." McCarten also lamented that the filmmakers were "unable to indicate more than fleetingly the real problem of the hero—homosexuality, which is, of course, a taboo subject in American movies."[15] The Monthly Film Bulletin shared that regret, writing, "Censorship difficulties admittedly make it impossible to show homosexuality as the root of Brick's problem, but Brooks does not appear to have the skill to make convincing the motives he has substituted. Most of Williams' exhilarating dialogue has been left out or emasculated, and the screenplay fails to harmonise the revised characterisation of Brick with the author's original conception."[16]

The film received six Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Best Actor (Newman), Best Actress (Taylor), Best Director (Brooks), Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium, and Best Cinematography, Color (William Daniels). Cat may have been too controversial for the Academy voters; the film eventually didn't win any Oscars and the Best Picture award went to Gigi, another Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer production, that year. Ives won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for The Big Country at the same ceremony.

Box office

The film was a hit with audiences. According to MGM records the film earned $7,660,000 in the US and Canada and $3,625,000 elsewhere resulting in a profit of $2,428,000.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ "M-G-M Sets 'Cat' for 100 Labor Day Dates". Motion Picture Daily: 2. August 13, 1958. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study .

- ↑ Variety film review; August 13, 1958, page 6.

- ↑ Harrison's Reports film review; August 16, 1958, page 130.

- ↑ Hostetler, Gerry CHS Olympian Floyd Simmons Passes Charlotte Observer April 11, 2008

- ↑ "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, TCM Database". TCM.com. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ Parish, James Robert; Mank, Gregory W.; Stanke, Don E. (1978). The Hollywood Beauties. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House Publishers. p. 326. ISBN 0-87000-412-3.

- ↑ Parish, p. 329

- ↑ Billington, Michael. "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof: Tennessee Williams's southern discomfort". theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (September 19, 1958). "The Fur Flies in 'Cat on a Hot Tin Roof'". The New York Times: 24.

- ↑ "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof". Variety: 6. August 13, 1958.

- ↑ "'Cat on a Hot Tin Roof' with Elizabeth Taylor, Paul Newman and Burl Ives". Harrison's Reports: 130. August 16, 1958.

- ↑ Coe, Richard L. (September 4, 1958). "Screen 'Cat' is a Marvel". The Washington Post: C12.

- ↑ Scheuer, Philip K. (August 24, 1958). "'Cat on a Hot Tin Roof' Has Artistic Merit, Shock Value". Los Angeles Times (Part V): 1–2.

- ↑ McCarten, John (September 27, 1958). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 162.

- ↑ "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 25 (298): 139. November 1958.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (film) |