Cardiac catheterization

| Cardiac catheterization | |

|---|---|

Cardiac catheterization lab | |

| Specialty | cardiology |

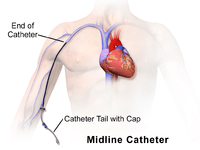

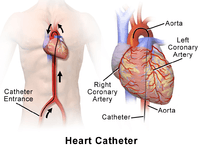

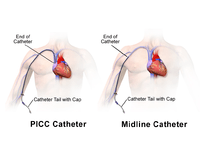

Cardiac catheterization (heart cath) is the insertion of a catheter into a chamber or vessel of the heart. This is done both for diagnostic and interventional purposes. Subsets of this technique are mainly coronary catheterization, involving the catheterization of the coronary arteries, and catheterization of cardiac chambers and valves of the cardiac system.

Procedure

"Cardiac catheterization" is a general term for a group of procedures that are performed using this method, such as coronary angiography and left ventricle angiography. Once the catheter is in place, it can be used to perform a number of procedures including, coronary angioplasty, balloon septostomy, electrophysiology study or catheter ablation.

Procedures can be diagnostic or therapeutic. For example, coronary angiography is a diagnostic procedure that allows the interventional cardiologist to visualize the coronary vessels. Percutaneous coronary intervention, however, involves the use of mechanical stents to increase blood flow to previously blocked (or occluded) vessels. Other common diagnostic procedures include measuring pressures throughout the four chambers of the heart and evaluating pressure differences across the major heart valves. Interventional cardiologists can also use cardiac catheterization to estimate the cardiac output, the amount of blood pumped by the heart per minute.[1] Cardiac catheterization can be used as part of a therapeutic regimen to improve outcomes for survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.[2]

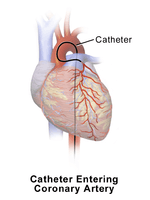

Cardiac catheterization requires the use of fluoroscopy to visualize the path of the catheter as it enters the heart or as it enters the coronary arteries. The coronary arteries are known as "epicardial vessels" as they are located in the epicardium, the outermost layer of the heart.[3] Fluoroscopy can be conceptually described as continuous x-rays. The use of fluoroscopy requires radiopaque contrast, which in rare cases can lead to contrast-induced kidney injury (see Contrast-induced nephropathy). Patients are constantly exposed to low doses of ionizing radiation during procedures.[4] Ideal table positioning between the x-ray source and receiver, and radiation monitoring via thermoluminescent dosimetry, are two main ways of reducing a person's exposure to radiation.[4] People with certain comorbidities (people who have more than one condition at the same time) have a higher risk of adverse events during the cardiac catheterization procedure.[4] These comorbidity conditions include aortic aneurysm, aortic stenosis, extensive three-vessel coronary artery disease, diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, obesity, renal insufficiency, and unstable angina.[5]

There are two major categories of cardiac catheterization:[6]

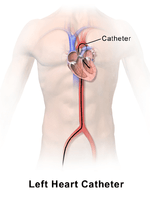

- Left heart catheterization allows for direct intervention in cases of coronary artery occlusion. This technique is also used to assess the amount of occlusion (or blockage) in a coronary artery, often described as a percentage of occlusion. A thin, flexible wire is inserted into either the femoral artery or the radial artery and threaded toward the heart until it is in the ascending aorta. Radial access is not associated with an increased risk of stroke over femoral access.[7] At this point, a catheter is guided over the wire into the ascending aorta, where it can be maneuvered into the coronary arteries through the coronary ostia.[5] In this position, the interventional cardiologist can inject contrast and visualize the flow through the vessel. If necessary, the physician can utilize percutaneous coronary intervention techniques, including the use of a stent (either bare-metal or drug-eluting) to open the blocked vessel and restore appropriate blood flow. In general, occlusions greater than 70% of the width of the vessel lumen are thought to require intervention. However, in cases where multiple vessels are blocked (so-called "three-vessel disease"), the interventional cardiologist may opt instead to refer the patient to a cardiothoracic surgeon for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG; see Coronary artery bypass surgery) surgery.

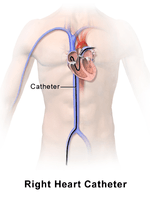

- Right heart catheterization allows the physician to determine the pressures within the heart (intracardiac pressures). In this case, the heart is most often accessed via the femoral vein; neither the femoral artery nor the radial artery are used. Values are commonly obtained for the right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary arteries, and for the pulmonary capillary "wedge" pressures, which approximate the pressure values of the left-sided heart chambers. Right heart catheterizations also allow the physician to estimate the cardiac output, the amount of blood that flows from the heart each minute, and the cardiac index, a hemodynamic parameter that relates the cardiac output to a patient's body surface area. Determination of cardiac output can be done by releasing a small amount of saline solution (either chilled or at room temperature) in one area of the heart and measuring the drop in blood temperature over time in another area of the heart. It is important to note that the coronary arteries are not accessed during a right heart catheterization.

Coronary catheterization

Main page: Coronary catheterization

Indications for diagnostic use of coronary catheterization

Patients without cardiac symptoms or high-risk markers for a heart problem should not have a coronary catheterization to screen for problems.

Indications for cardiac catheterization include the following:

- Heart Attack (includes ST elevation MI, Non-ST Elevation MI, Unstable Angina)

- Abnormal Stress Test

- New-onset unexplained heart failure

- Survival of sudden cardiac death or dangerous cardiac arrhythmia

- Persistent chest pain despite optimal medical therapy

- Workup of suspected Prinzmetal Angina (coronary vasospasm)

Right heart catheterization, along with pulmonary function testing and other testing should be done to confirm pulmonary hypertension prior to having vasoactive pharmacologic treatments approved and initiated.[9]

Investigative techniques used with coronary catheterization

- to measure intracardiac and intravascular blood pressures

- to take tissue samples for biopsy

- to inject various agents for measuring blood flow in the heart; also to detect and quantify the presence of an intracardiac shunt

- to inject contrast agents in order to study the shape of the heart vessels and chambers and how they change as the heart beats

Catheterization of chambers and valves

Catheterization of cardiac chambers and valves may be performed at the same time as a coronary catheterization, and may also involve nearby major vessels, such as the aorta. It is the main method of cardiac ventriculography (another being radionuclide ventriculography, whose use has largely been replaced by echocardiography).

Cardiac catheterization can be used to diagnose or assess severity of valvular stenosis by measuring elevated pressure gradients across cardiac valves.[10]

This is also the procedure used in balloon septostomy, which is the widening of a foramen ovale, patent foramen ovale (PFO), or atrial septal defect (ASD) using a balloon catheter.

History

The history of cardiac catheterization dates back to Stephen Hales (1677-1761) and Claude Bernard (1813-1878), who both used it on animal models. Clinical application of cardiac catheterization begins with Werner Forssmann in 1929, who inserted a catheter into the vein of his own forearm, guided it fluoroscopically into his right atrium, and took an X-ray picture of it.[11] During World War II, André Frédéric Cournand, a physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, then Columbia-Bellevue, opened the first catheterization lab. In 1956, Forssmann and Dr. Cournand were co-recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the development of cardiac catheterization. However, even after this achievement, hospital administrators removed Forssmann from his position owing to his unorthodox methods.[11]

Dr. Eugene A. Stead, founder of the Physician Assistant profession, also performed research in the 1940s which paved the way for cardiac catheterization in medicine today.

References

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill. 2015.

- ↑ Camuglia, Anthony C.; Randhawa, Varinder K.; Lavi, Shahar; Walters, Darren L. (November 2014). "Cardiac catheterization is associated with superior outcomes for survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest: review and meta-analysis". Resuscitation. 85 (11): 1533–1540. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.025. ISSN 1873-1570. PMID 25195073.

- ↑ Malouf JF, Edwards WD, Tajik A, Seward JB. Chapter 4. Functional Anatomy of the Heart. In: Fuster V, Walsh RA, Harrington RA. eds. Hurst's The Heart, 13e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=376&Sectionid=40279729. Accessed May 09, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Christopoulos, Georgios; Makke, Lorenza; Christakopoulos, Georgios; Kotsia, Anna; Rangan, Bavana V.; Roesle, Michele; Haagen, Donald; Kumbhani, Dharam J.; Chambers, Charles E. (2016-02-01). "Optimizing Radiation Safety in the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory: A Practical Approach". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions: Official Journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 87 (2): 291–301. doi:10.1002/ccd.25959. ISSN 1522-726X. PMID 26526181.

- 1 2 The cardiac catheterization handbook. Kern, Morton J.,, Sorajja, Paul,, Lim, Michael J., (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323341554. OCLC 910964299.

- ↑ Leopold JA, Faxon DP. Diagnostic Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Angiography. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J.eds. 'Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1130&Sectionid=79742087. Accessed May 09, 2015.

- ↑ Sirker, Alex; Kwok, Chun Shing; Kotronias, Rafail; Bagur, Rodrigo; Bertrand, Olivier; Butler, Robert; Berry, Colin; Nolan, James; Oldroyd, Keith (November 2016). "Influence of access site choice for cardiac catheterization on risk of adverse neurological events: A systematic review and meta-analysis". American Heart Journal. 181: 107–119. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2016.06.027. ISSN 1097-6744. PMID 27823682.

- ↑ Sabatine, edited by Marc S. (2011). Pocket medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 1608319059.

- ↑ American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society (September 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Chest Physicians and American Thoracic Society, retrieved 6 January 2013

- ↑ Grossman & Baim's cardiac catheterization, angiography, and intervention. Moscucci, Mauro, (Eighth edition). Philadelphia. p. 272. ISBN 9781451127409. OCLC 829739969.

- 1 2 West, JB (1 October 2017). "The beginnings of cardiac catheterization and the resulting impact on pulmonary medicine". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 313 (4): L651–L658. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00133.2017. PMID 28839102.

External links

- MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Cardiac catheterization

- eMedicine: Cardiac Catheterization (Left Heart)