Caproni Campini N.1

| Caproni Campini N.1 | |

|---|---|

| |

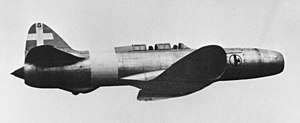

| A Caproni Campini N.1 in flight. Note the canopies left open to cool down the cockpit. | |

| Role | Experimental aircraft |

| National origin | Italy |

| Manufacturer | Caproni |

| Designer | Secondo Campini |

| First flight | 27 August 1940 |

| Status | Prototypes only |

| Primary user | Regia Aeronautica |

| Number built | 2 |

| Developed into | Caproni Campini Ca.183bis |

The Caproni Campini N.1, also known as the C.C.2, was an experimental jet aircraft built in the 1930s by Italian aircraft manufacturer Caproni. The N.1 first flew in 1940 and was briefly regarded as the first successful jet-powered aircraft in history, before news emerged of the German Heinkel He 178's first flight a year earlier.[1]

During 1931, Italian aeronautics engineer Secondo Campini submitted his studies on jet propulsion, including a proposal for a so-called thermo-jet to power an aircraft. Following a high-profile demonstration of a jet-powered boat in Venice, which was the world's first vehicle to harness jet propulsion, Campini was rewarded with an initial contract issued by the Italian government to develop and manufacture his envisioned engine. During 1934, the Regia Aeronautica (the Italian Air Force) granted its approval to proceed with the production of a pair of jet-powered prototype aircraft. To produce this aircraft, which was officially designated as the N.1, Campini formed an arrangement with the larger Caproni aviation manufacturer.

The N.1 was powered by a motorjet, a type of jet engine in which the compressor is driven by a conventional reciprocating engine. It was an experimental aircraft, designed to demonstrate the practicality of jet propulsion. On 27 August 1940, the maiden flight of the N.1 occurred at Caproni facility in Taliedo, outside of Milan, flown by renowned test pilot Mario De Bernardi. Subsequent flight tests with the first prototype led to a maximum speed of roughly 320 MPH being recorded. On 30 November 1941, the second prototype was flown by pilot De Bernardi and engineer Giovanni Pedace from Milan's Linate Airport to Rome's Guidonia Airport, in a highly publicised event that included a fly-past over Rome and a reception with Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Testing of the N.1 continued into 1943, by which point work on the project was disrupted by the Allied invasion of Italy.

The N.1 achieved mixed results, while it was perceived and commended as a crucial milestone in aviation (until the revelation of the He 178's earlier flight), the performance of the aircraft was underwhelming; specifically, it was slower than some existing conventional aircraft of the era, while the motorjet engine was incapable of producing sufficient thrust to deliver viable performance levels to be used in a fighter aircraft. Campini embarked on further projects, but these would involve the indigenously-developed motorjet being substituted with a German-provided turbojet. As such, the N.1 programme never led to any operational combat aircraft, and the motorjet design was soon superseded by more powerful turbojets. Only one of the two examples of the N.1 to have been constructed has survived to the present day.

Development

During 1931, Italian aeronautics engineer Secondo Campini submitted a report to the Regia Aeronautica (the Italian Air Force) on the potential of jet propulsion; this report included his proposals for one such implementation, which he referred to as a thermo-jet. That same year, Campini established his own company to pursue both the development of and demonstrations of the practical applications for this engine. Accordingly, during the following year, he demonstrated a jet-powered boat in Venice, which had the distinction of being the world's first vehicle to harness jet propulsion and attained a top speed of 28 knots during initial testing. This high-profile experiment generated considerable attention, including from Italian government officials; shortly thereafter, Campini received a government-issued contract to produce an initial pair of engines for testing purposes.

During 1934, the Regia Aeronautica granted approval for the development of a pair of prototypes, along with a static testbed, for the purpose of demonstrating the principle of a jet aircraft, as well as to explore potential military applications. As his company lacked the necessary industrial infrastructure for such endeavours, Campini formed an arrangement with the larger Caproni aviation manufacturer, under which the latter provided the required material assistance for the manufacturing of the prototypes.[2] Under this relationship, Campini developed his design, which later received the official Italian Air Force designation of N.1.[3]

Historian Nathanial Edwards has contrasted the relative openness of Italian early jet development work against the high levels of secrecy present within other nation's programmes, such as Britain and Germany.[4] He speculated that this was due to desire of the Italian government to be perceived as possessing a modern and advanced aviation industry, being keen to acquire national prestige and adoration for such achievements. Edwards went onto claim that the practicality of the N.1 design was undermined by political pressure to speed the programme along so that Italy would be more likely to be the first country in the world to perform a jet-powered flight.[4]

Design

The Caproni Campini N.1 was an experimental aircraft, designed to demonstrate the practicality of jet propulsion and its viability as an engine for aircraft. In terms of its basic configuration, it was composed entirely out of duralumin and had a monoplane layout, being outfitted with an elliptical wing. The initial aircraft lacked elements such as a pressurised cabin; however, these improvements were featured on the second prototype. However, flight testing quickly revealed that, due to the excessive heat output of the pioneering propulsion system, the canopy would have to be left permanently open as a mitigating measure.[5]

The engine of the N.1 featured a radical design, differing substantially from the later-produced turbojet and turbofan engines. One crucial difference in Campini's design was the compressor – a three-stage, variable-incidence one, located forward of the cockpit – was driven by a conventional piston engine, this being a 900 hp (670 kW), liquid-cooled Isotta Fraschini unit.[6] The airflow provided by the compressor was used to cool down the engine prior to being mixed with the engine's exhaust gases, thus recovering most of the heat energy that in traditional piston-propeller designs would be discharged overboard. A ring-shaped burner would then inject fuel into the gas flow and ignite it, immediately before the exhaust nozzle, to further increase thrust.[7][3]

In practice, the engine was able to provide sufficient thrust for flight even without activating the rear burner, making the design somehow similar to a ducted fan coupled with an afterburner.[5] Campini referred to this configuration as being a thermojet, although it has since become commonly known as motorjet.[8] However, despite the elaborate design, the relatively small size of the duct limited the mass flow and thus the propulsive efficiency of the engine. In modern designs this is offset through high overall pressure ratios, which could not be achieved on the N.1, therefore resulting in relatively low thrust and poor fuel efficiency.[9] Ground tests performed with the static testbed produced a thrust of around 700 kgf (1,500 lbf).[2]

Operational history

On 27 August 1940, the maiden flight of the N.1 occurred at Caproni facility in Taliedo, outside of Milan. It was performed by test pilot Mario De Bernardi, an accomplished aviation figure who had previously been responsible for setting several world records in seaplanes and aerobatic aircraft; he would go on to conduct the majority of the N.1's test flights..[10] This initial flight lasted for ten minutes, during which De Bernardi deliberately kept the speed of the prototype below 225 MPH, less than half throttle, due to doubts surrounding the untested airframe's ability to withstand the potentially high loading that it would be subject to when flown at high speeds. Since the first flight of the jet-powered Heinkel He 178, a year before to the day, at the time had not yet been made public, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale recorded the event as the first successful flight by a jet aeroplane.[2]

Subsequent flight tests with the first prototype led to a maximum speed of roughly 320 MPH being recorded. However, testing revealed several issues with the engine; particularly the determination that it lacked the ability to produce sufficient thrust to achieve high performance if it were to be matched to a strengthened airframe to withstand the high loading pressures.[3] One of the more unusual issues to be encountered during the flight test programme was the considerable amount of engine heat which was conveyed into the cockpit; in order to fly the aircraft, the crew were forced to keep the canopy open throughout the flight, which effectively vented the heat.[5]

According to aviation author Sterling Michael Pavelec, the first flight of the N.1 had "showed that the plane was a failure...[being] heavy and underpowered"; he observed that the pre-existing Caproni Vizzola F.4 (a conventionally-powered aircraft) was capable of a greater maximum speed.[8] Pavelec attributed the underwhelming performance have been a product of limited national resources which had not only undermined the potential performance for any turbojet programme but also mainstream piston engines, which he claimed to be typically underfunded and prone to technical difficulties, leading to Italian engine manufacturers mainly restricting themselves to traditional and low-powered models while German industry became increasingly relied upon for the production of high-powered engines.[11]

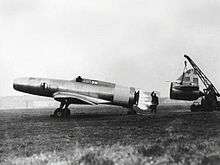

On 30 November 1941, the second prototype was flown by pilot De Bernardi and engineer Giovanni Pedace from Milan's Linate Airport to Rome's Guidonia Airport, in a highly publicised event that included a fly-past over Rome and a reception with Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. It held the distinction of being the first cross-country jet flight to occur, as well as being the first mail delivery to be performed by a jet-powered aircraft. The flight included a stopover at Pisa, possibly to refuel, and was conducted entirely without the use of the rear burner.[2][7]

Irrespective of its shortcomings, the N.1 served as a demonstrator and pioneer of jet technology being applied to the field of aviation. The November 1941 flight resulted in no less than 33 nations, some of which being at a state of war with Italy, sending their official congratulations in recognition of the achievement; in this respect, the N.1 could be viewed as having been relatively successful. Aircraft designers and engineers around the world paid attention to the findings; according to economics author Harrison Mark, Soviet aircraft design bureau TsAGI obtained details on the N.1 programme and were encouraged to pursue work on a similar design; as such, there is a basis for stating that the design of the N.1 influenced subsequent early jet aircraft.[12]

The experience gained from the N.1 proved influential to Campini. Having formed a partnership with another Italian aircraft company, Reggiane, and aircraft designer Roberto Longhi, he commenced work on an entirely new design; this would have represented a significant departure from the N.1, including the decision to abandon the indigenous Italian engine it used in favour of a German-provided counterpart. This aircraft, the Reggiane Re.2007, was envisioned to be a combat-capable fighter, unlike the purely experimental N.1. Campini would go on to work on a number of jet-powered aircraft, including the Boeing B-47 Stratojet.

Testing of the two N.1 prototypes continued into 1943, however the programme was heavily hindered by events of the Second World War, specifically the extensive Allied invasion of Italy which would see the collapse of the nation's Fascist government. During an Allied bombing raised upon Caproni's factory in Taliedo, one of the experimental aircraft was destroyed. After the conflict had reached its end in 1945, one of the remaining prototypes was transported to the United Kingdom for study at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in Farnborough. This aircraft was subsequently lost and its whereabouts have remained unknown.[2]

Operators

Surviving aircraft

The only surviving prototype is now on display at the Italian Air Force Museum at Vigna di Valle, near Rome, while the ground testbed, consisting of only the fuselage, is on display at the National Museum of Science and Technology in Milan.[11]

Specifications

Data from Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft [13]

General characteristics

- Crew: two

- Length: 13.10 m (43 ft)

- Wingspan: 15.85 m (52 ft)

- Height: 4.7 m (15 ft 5 in)

- Wing area: 36.00 m² (387.5 ft²)

- Empty weight: 3,640 kg (8,024 lb)

- Max. takeoff weight: 4,195 kg (9,250 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × 900 hp (670 kW) Isotta Fraschini L.121 R.C.40 engine-driven three-stage, variable-pitch axial compressor motorjet, producing 6.9 kN (1,550 lbf)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 375 km/h (233 mph)

- Service ceiling: 4,000 m (13,300 ft)

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

References

Citations

- ↑ Enzo Angelucci; Paolo Matricardi. Campini Caproni C.C.2 in Guida agli Aeroplani di tutto il Mondo. Mondadori Editore. Milano, 1979. Vol. 5, pp. 218-219.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Storia del Campini Caproni" (in Italian). National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 Pavelec 2007, p. 5.

- 1 2 Edwards, Nathanial. "Flight as Propaganda in Fascist Italy." World At War Magazine, Late 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Campini Caproni 2". Museo Storico di Vigna di Valle (in Italian). Aeronautic Militare Italiana. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ Golly 1996, pp. 32-33.

- 1 2 Smith, Geoffrey (19 February 1942). "More About Jet Propulsion". Flight. Vol. XLI no. 1730. p. 153. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- 1 2 Pavelec 2007, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Marc de Piolenc and George Wright, "Ducted Fan Design", Marc de Piolenc, 2001. p. 138.

- ↑ "Italian Air Scooter". Flight, 10 October 1952. p. 471.

- 1 2 Pavelec 2007, p. 6.

- ↑ Mark 2014, p. 235.

- ↑ Morse, Stan, ed. (1982). Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft. Orbis Publishing. OCLC 16544050.

Bibliography

- Golly, John. Jet: Frank Whittle and the Invention of the Jet Engine. Datum Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-90747-201-0.

- Mark, Harrison. The Economics Of Coercion And Conflict. World Scientific, 2014. ISBN 9-81458-335-9.

- Morse, Stan. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft. Orbis Publishing, 1982.

- Pavelec, Sterling Michael. The jet race and the Second World War. Praeger Security International: Westport, Connecticut. 2007. ISBN 0-275-99355-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caproni Campini N.1. |