Camille Cosby

| Camille Cosby | |

|---|---|

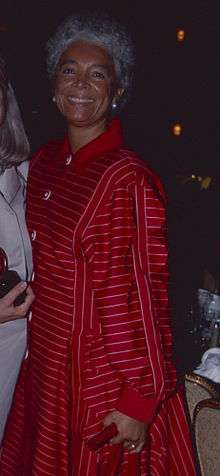

Camille Cosby at the 2000 Peabody Awards | |

| Born |

Camille Olivia Hanks March 20, 1944 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Camille O. Cosby, Camille Olivia Hanks Cosby[1] |

| Alma mater |

University of Maryland University of Massachusetts (PhD) |

| Occupation | Television producer |

| Known for | Philanthropy |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 5, including Erika Cosby and Ennis Cosby |

| Awards | 1992 Candace Award[2] |

Camille Olivia Cosby (née Hanks; born March 20, 1944[3]) is an American television producer, author, philanthropist, and the wife of comedian Bill Cosby. The character of Clair Huxtable from The Cosby Show was based on her.

Early life

Camille was born Camille Olivia Hanks on March 20, 1944, in Washington D.C., to Guy A. Hanks Sr. and Catherine C. Hanks. She grew up in Norbeck, Maryland, just outside Washington. She is the oldest of four children and is a distant cousin of Nancy Hanks Lincoln, mother of United States President Abraham Lincoln.[4][5][6] Through Lincoln, she is a distant cousin of American actor Tom Hanks.[7]

Cosby's father was a chemist at Walter Reed General Hospital and her mother worked at a nursery. Both of Cosby's parents had college educations, with her father earning a graduate degree from Fisk University and her mother earning an undergraduate degree from Howard University.[8][9]

Cosby attended private Catholic schools. First, she attended St. Cyprian’s, followed by St. Cecilia’s Academy.[10] After high school, Cosby studied psychology at the University of Maryland. While a student there, she went on a blind date during her sophomore year with Bill Cosby.[11] Engaged shortly after they started dating, the pair married on January 25, 1964.[9]

Following their marriage, Cosby and her husband had five children: Erika (born 1965), Erinn (born 1966), Ennis (April 15, 1969 – January 16, 1997), Ensa (April 8, 1973 – February 23, 2018),[12][13] and Evin (born 1976). Ennis was murdered on January 16, 1997 at age 27. Her daughter Ensa died February 23, 2018 of renal disease while awaiting a kidney transplant. She was 44.[14]

Career and education

Cosby acts as manager for her husband and has been depicted as a "shrewd businesswoman." During an interview with Ebony Magazine, Bill Cosby stated, "People would rather deal with me than with Camille. She's rough to deal with when it comes to my business."[15] She also "helps in the development of her husband's material", including suggestions for The Cosby Show, suggesting the Huxtable family be middle rather than working class.[4]

Cosby has been a supporter of African American literature, writing forewords for several authors. In 1993, she wrote the foreword for Thelma Williams' Our Family Table: Recipes And Food Memories From African-american Life Models.[16] In 2009, Cosby wrote the foreword for Dear Success Seeker: Wisdom from Outstanding Women by Dr. Michele R. Wright.[17] In 2014, she did the foreword for The Man from Essence: Creating a Magazine for Black Women, a book by Edward Lewis of Essence.[18]

In 1994, Cosby released Television's Imageable Influences: The Self-Perception of Young African-Americans, a book that "dramatically charts the damaging impact of derogatory images of African Americans produced in our media establishments."[19] The book was originally intended to be the subject of her thesis for her doctorate degree.

In 2001, Cosby worked with David C. Driskell for his book The Other Side of Color: African American Art in the Collection of Camille O. and William H. Cosby Jr., which focused on the Cosby's art collection.[20]

Together, Cosby and Renee Poussaint edited A Wealth of Wisdom: Legendary African American Elders Speak in 2004.[21]

Cosby was co producer for the Broadway play Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters' First 100 Years, based on the book Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters' First 100 Years by Sarah "Sadie" L. Delany and A. Elizabeth "Bessie" Delany with Amy Hill Hearth.[22]

Following the success of the show, Cosby acquired the film, stage and television rights to the story and later acted as executive producer for the 1999 made-for-television movie of the same name.[23][24][25] In June 1987, Howard University in Washington, D.C., presented Cosby with a Doctor of Humane Letters, an honorary doctoral degree.[26]

In 1990, Cosby earned a master's degree from the University of Massachusetts, followed by a Ph.D. in 1992.[27] In an interview with Oprah Winfrey, Cosby stated, "I became keenly aware of myself in my mid thirties. I went through a transition. I decided to go back to school, because I had dropped out of college to marry Bill when I was 19. I had five children, and I decided to go back. I didn't feel fulfilled educationally. I dropped out of school at the end of my sophomore year. So I went back, and when I did, my self-esteem grew. I got my master's, then decided to get my doctoral degree. Education helped me to come out of myself."[11]

Philanthropy

Cosby's history of philanthropy includes donations to schools and educational foundations. Her philanthropic memberships include Operation PUSH, The United Negro College Fund, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the National Council of Negro Women, and Jesse Jackson's National Rainbow Coalition.[28]

Beginning in the start of the 1980s, Cosby and her husband donated $100,000 to Central State University, a historically black university in Ohio, with a gift of $325,000 following in 1987. In September 1989, CSU held the "Camille and Bill Cosby Cleveland Football Classic" in honor of their contributions to the school.[29]

In January 1987, the Cosbys donated $1.3 million to Fisk University.[30] In November 1988, they donated $20 million to Atlanta's Spelman College, a women's college with a predominantly Black enrollment. According to The New York Times, the gift was the largest donation to a black college in American history.[31] The college has since named the five story 92,000 square foot Camille Olivia Hanks Cosby Academic Center after Cosby.[32][33]

A few months after the Spellman donation, Cosby and her husband donated $800,000 to Meharry Medical College as well as $750,000 to Bethune-Cookman University.[34]

In July 1992, during a gala held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Coalition of 100 Black Women awarded Cosby the Candace Award, a recognition of minority women that have made valuable contributions to their communities.[2]

In April 2005, Cosby donated $2 million to Saint Frances Academy of Baltimore High School. Because of the donation, the school was able to endow 16 scholarships in Cosby's name.[35]

Bill Cosby sexual assault allegations

Cosby has defended her husband against accusations that he has sexually assaulted women over his career. While acknowledging he has cheated on her, she has said that he is not a rapist.[36] In 2014, Cosby released a statement saying that her husband had been the victim of unvetted accusations: "The man I met, and fell in love with, and whom I continue to love, is the man you all knew through his work. He is a kind man... and a wonderful husband, father and friend."[37]

In the deposition of May 2016, Cosby invoked spousal privilege when asked whether Bill had been faithful to her.[38]

On May 3, 2018, after her husband's conviction for sexual assault, Cosby released a three-page statement defending her husband in which she compared her husband's conviction to the racially charged killing of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old boy who was lynched after a white woman said she was offended by him in her family's grocery store. Cosby also called for a criminal investigation into the Pennsylvania prosecutor behind the conviction.[39]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Credit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | The Cosby Show | Extra (uncredited) | Episode: "Off to the Races" |

| 1987 | Bill Cosby: 49 | Director | |

| 1994 | No Dreams Deferred | Executive producer | |

| 1994 | The American Experience | Special funding | Episode: "Malcolm X: Make It Plain" |

| 1996 | Bill Cosby: Mr. Sapolsky, with Love | Co-Executive Producer | |

| 1997 | 10th Anniversary Essence Awards | Self | |

| 1999 | Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters' First 100 Years | Executive Producer | Television movie |

| 2000 | The Oprah Winfrey Show | Self | Episode November 27, 2000 |

| 2000 | Ennis' Gift | Executive Producer | Documentary film |

| 2001 | Essence Awards | Self | |

| 2002 | Sylvia's Path | Executive Producer | Television movie |

| 2004 | Fatherhood | Special thanks | |

| 2004 | Fat Albert | Executive Producer | |

| 2010 | Queen Victoria's Wedding | Special thanks | Film short |

| 2010-2012 | OBKB | Executive Producer | 38 episodes |

| 2014 | Extra | Self | Archive footage - Episode #21.55 |

| 2014 | CNN Newsroom | Self | Archive footage - November 21, 2014 episode |

| 2014 | OMG Insider | Self | Archive footage - December 16, 2014 episode |

References

- ↑ "Oprah Talks to Camille Cosby". Oprah Magazine. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- 1 2 "Camille Cosby, Kathleen Battle Win Candace Awards". Jet. 82 (13): 16. July 20, 1992.

- ↑ Contemporary Black Biography (Volume 14), p. 72.

- 1 2 Whitaker, Matthew C. (2011). Icons of Black America: Breaking Barriers and Crossing Boundaries, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 194. ISBN 9780313376429.

- ↑ Smith, Jessie Carney (1992). Notable Black American Women. Gale Research. p. 228. ISBN 9780810347496.

- ↑ Roig-Franzia,, Manuel; Thompson, Krissah; Flaherty, Mary Pat (December 23, 2014). "Camille Cosby: A life spent juggling her role as public figure with desire to be private". Washington Post.

- ↑ https://www.moviefone.com/2013/10/12/tom-hanks-25-things-you-didnt-know/

- ↑ Whitaker, Mark (2014). Cosby: His Life and Times. Simon and Schuster. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9781451697995.

- 1 2 "Life With Bill Cosby". Ebony. 21 (11): 36. Sep 1996.

- ↑ Roig-Franzia, Manuel (23 Dec 2014). "Camille Cosby: A life spent juggling her role as public figure with desire to be private". Washington Post. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- 1 2 Telusma, Blue (November 20, 2014). "Camille Cosby, another victim of the controversy?" (November 20, 2014). CNN. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ California Birth Index 1905-1995

- ↑ Respers France, Lisa. "Ensa Cosby, daughter of Bill Cosby, dies at 44".

- ↑ "Bill Cosby Biography (1937-)". Film Reference. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Norment, Lynn. "Three Great Love Stories". Ebony: 152. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ↑ Williams, Thelma (1993). Our Family Table: Recipes And Food Memories From African-american Life Models. Diane Pub Co. ISBN 978-0756780937.

- ↑ Wright, Michele R. (2009). Dear Success Seeker: Wisdom from Outstanding Women. 978-1416570790.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Lewis, Edward (2014). The Man from Essence: Creating a Magazine for Black Women. Atria Books. ISBN 978-1476703480.

- ↑ "Camille Cosby's Book Explores Negative Images of Blacks in Media". Jet. 87 (16): 60. Feb 1995.

- ↑ Driskell, David C. (2001). The Other Side of Color: African American Art in the Collection of Camille O. and William H. Cosby Jr. Pomegranate. ISBN 978-0764914553.

- ↑ A Wealth of Wisdom: Legendary African American Elders Speak. Atria. 2004. ISBN 978-0743478922.

- ↑ "Camille Cosby's Broadway Play, 'Having Our Say', Wins Critical Acclaim". Jet. 87 (25): 62–64. May 1, 1995.

- ↑ "Sarah 'Sadie' Delany, 109, Subject of Best-Selling Memoir and Broadway Play, Dies". Jet. 95 (12): 16. February 22, 1999.

- ↑ Smith, Jessie Carney (1996). Notable Black American Women, Book 2. VNR AG. p. 173. ISBN 9780810391772.

- ↑ Ross, Lawrence C. (January 1, 2001). The Divine Nine: The History of African American Fraternities and Sororities. Kensington Books. p. 98. ISBN 9780758202703.

- ↑ "Camille Cosby Delivers Howard Graduation Address; Receives Honorary Degree". Jet. 72 (10): 24. June 1, 1987. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Millionairess Camille Cosby Says She Had to Earn PhD 'Because You Have To Do What You Urge Others To Do'". Jet. 82 (8): 12. 1992.

- ↑ "Bill and Camille Cosby Discuss the Secrets of Living a Better Life". Jet. 76 (26): 59. October 2, 1989.

- ↑ "Central State U. Honors Cosby Family Generosity at Cleveland Classic". Jet. 76 (23): 10. September 11, 1989.

- ↑ "Bill and Camille Cosby Make $1.3 Million Gift to Aid Fisk University". Jet. 71 (16): 52. January 12, 1987.

- ↑ Daniels, Lee A. (November 8, 1988). "A Black College Gets Cosby Gift Of $20 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Spelman College in Atlanta Opens Center Honoring Dr. Camille Cosby". Jet. 89 (18): 22–23. March 18, 1996. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Bill and Camille Cosby Attend Ground Breaking for Spelman's Cosby Center". Jet. 80 (2): 5. April 29, 1991.

- ↑ "Bill and Camille Cosby Give $1.5 Million To Meharry and Bethune-Cookman Colleges". Jet. 75 (14): 5. January 9, 1989. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Camille Cosby Donates $2 Million to High School in Baltimore". Jet. 107 (17): 41. April 25, 2005.

- ↑ Brown, Stacy (12 Jul 2015). "Bill Cosby's wife says accusers 'consented' to drugs and sex". New York Post. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Karimi, Faith (30 December 2015). "Bill Cosby's lawyers fight subpoena against his wife, Camille Cosby". CNN. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Winter, Tom (20 May 2016). "Bill Cosby's Wife, Camille Cosby, Defends Comedian in Unsealed Deposition". NBC. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Wootson Jr., Cleve R.; Rao, Sonia (May 3, 2018). "Camille Cosby on her husband's conviction: 'This is mob justice, not real justice'". Washington Post.

External links

- Camille Cosby on IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN