CRYM

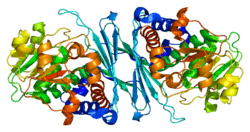

Mu-crystallin homolog also known as NADP-regulated thyroid-hormone-binding protein (THBP) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CRYM gene. Multiple alternatively spliced transcript variants have been found for this gene.[5][6]

Function

Crystallins are separated into two classes: taxon-specific and ubiquitous. The former class is also called phylogenetically-restricted crystallins. The latter class constitutes the major proteins of vertebrate eye lens and maintains the transparency and refractive index of the lens. This gene encodes a taxon-specific crystallin protein that binds NADPH and has sequence similarity to bacterial ornithine cyclodeaminases. The encoded protein does not perform a structural role in lens tissue, and instead it binds thyroid hormone for possible regulatory or developmental roles.[6]

Its enzyme function has been determined as a ketimine reductase, reducing cyclic ketimines to their reduced forms. Either NADH or NADPH can be used as cofactor. The most active substrate at pH 5.0 is aminoethylcysteine ketimine (AECK), however at neutral pH (pH 7.2) the most active substrate is 1-piperideine-2-carboxylate which is an important part of the pipecolic acid pathway. The active form of thyroxine, T3, has been found to be a potent inhibitor at nanomolar concentrations.[7]

Besides its role in lens biology, CRYM seems also to be involved in thyroid hormone signalling in other tissues. It could be demonstrated that CRYM mutations may cause deafness through thyroid hormone binding effects on the fibrocytes of the cochlea.[8] Disruption of the CRYM gene leads to decreased T3 concentrations in both tissues and serum without alteration of peripheral T3 action in vivo.[9][10]

The existence of intracellular thyroid hormone binding proteins has been postulated from mathematical modelling of pituitary-thyroid homeostasis.[11] Binding properties have been assumed to be similar to those of extracellular binding proteins,[12] however it is not clear, if THBP is the only intracellular thyroid hormone binding protein.

References

- 1 2 3 ENSG00000283922 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000103316, ENSG00000283922 - Ensembl, May 2017

- 1 2 3 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000030905 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

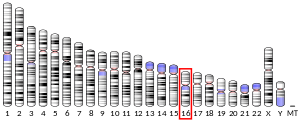

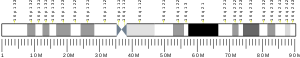

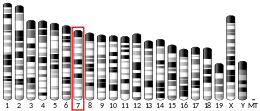

- ↑ Chen H, Phillips HA, Callen DF, Kim RY, Wistow GJ, Antonarakis SE (Feb 1993). "Localization of the human gene for mu-crystallin to chromosome 16p". Genomics. 14 (4): 1115–6. doi:10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80143-0. PMID 1478656.

- 1 2 "Entrez Gene: CRYM crystallin, mu".

- ↑ Hallen A, Cooper AJ, Jamie JF, Haynes PA, Willows RD (February 2011). "Mammalian forebrain ketimine reductase identified as μ-crystallin; potential regulation by thyroid hormones". J Neurochem. 118 (3): no–no. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07220.x. PMID 21332720.

- ↑ Oshima A, Suzuki S, Takumi Y, Hashizume K, Abe S, Usami S (June 2006). "CRYM mutations cause deafness through thyroid hormone binding properties in the fibrocytes of the cochlea". J. Med. Genet. 43 (6): e25. doi:10.1136/jmg.2005.034397. PMC 2564543. PMID 16740909.

- ↑ Abe S, Katagiri T, Saito-Hisaminato A, Usami S, Inoue Y, Tsunoda T, Nakamura Y (January 2003). "Identification of CRYM as a candidate responsible for nonsyndromic deafness, through cDNA microarray analysis of human cochlear and vestibular tissues". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1086/345398. PMC 420014. PMID 12471561.

- ↑ Suzuki S, Suzuki N, Mori J, Oshima A, Usami S, Hashizume K (April 2007). "micro-Crystallin as an intracellular 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine holder in vivo". Mol. Endocrinol. 21 (4): 885–94. doi:10.1210/me.2006-0403. PMID 17264173.

- ↑ Dietrich JW (2002). Der Hypophysen-Schilddrüsen-Regelkreis. Entwicklung und klinische Anwendung eines nichtlinearen Modells [The pituitary-thyroid control loop. Development and clinical application of a nonlinear model] (in German). Berlin: Logos-Verlag. ISBN 3-89722-850-5.

- ↑ Dietrich JW, Tesche A, Pickardt CR, Mitzdorf U (2004). "Thyrotropic Feedback Control: Evidence for an Additional Ultrashort Feedback Loop from Fractal Analysis". Cybernetics and Systems. 35 (4): 315–31. doi:10.1080/01969720490443354.

External links

- Human CRYM genome location and CRYM gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

Further reading

- Kim RY, Gasser R, Wistow GJ (1992). "mu-crystallin is a mammalian homologue of Agrobacterium ornithine cyclodeaminase and is expressed in human retina". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 (19): 9292–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.19.9292. PMC 50112. PMID 1384048.

- Vié MP, Blanchet P, Samson M, et al. (1996). "High affinity thyroid hormone-binding protein in human kidney: kinetic characterization and identification by photoaffinity labeling". Endocrinology. 137 (11): 4563–70. doi:10.1210/en.137.11.4563. PMID 8895318.

- Segovia L, Horwitz J, Gasser R, Wistow G (1998). "Two roles for mu-crystallin: a lens structural protein in diurnal marsupials and a possible enzyme in mammalian retinas". Mol. Vis. 3: 9. PMID 9285773.

- Vié MP, Evrard C, Osty J, et al. (1998). "Purification, molecular cloning, and functional expression of the human nicodinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate-regulated thyroid hormone-binding protein". Mol. Endocrinol. 11 (11): 1728–36. doi:10.1210/me.11.11.1728. PMID 9328354.

- Loftus BJ, Kim UJ, Sneddon VP, et al. (1999). "Genome duplications and other features in 12 Mb of DNA sequence from human chromosome 16p and 16q". Genomics. 60 (3): 295–308. doi:10.1006/geno.1999.5927. PMID 10493829.

- Abe S, Katagiri T, Saito-Hisaminato A, et al. (2003). "Identification of CRYM as a candidate responsible for nonsyndromic deafness, through cDNA microarray analysis of human cochlear and vestibular tissues". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1086/345398. PMC 420014. PMID 12471561.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, et al. (2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Reed PW, Corse AM, Porter NC, et al. (2007). "Abnormal expression of mu-crystallin in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Exp. Neurol. 205 (2): 583–6. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.009. PMID 17451686.