Burgundian treaty of 1548

The Burgundian treaty of 1548 (ratified on 26 June) settled the status of the Habsburg Netherlands within the Holy Roman Empire.

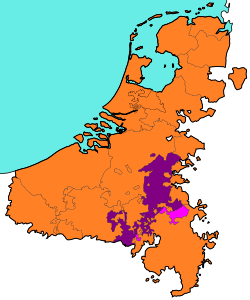

Essentially the work of Viglius van Aytta, it represents a first step towards the emergence of the Netherlands as an independent territory. It was made possible politically by the Schmalkaldic War resulting in the French loss of Artois and French Flanders. Administratively, a chancellery and tribunal was established at Mecheln which for the first time had as its jurisdiction "the Netherlands" exclusively. The treaty resulted in a significant shift of territories from the Lower Rhenish-Westphalian Circle to the Burgundian Circle. The newly formed administrative division of the empire now united all Burgundian territories, which were no longer subject to the Reichskammergericht. To compensate for its territorial gain, the Burgundian Circle was now obliged to pay taxes equivalent to those of two prince-electorates, and in war taxes towards the Turkish Wars even equivalent to three prince-electorates.

To ensure that the Burgundian territory now united in the Burgundian Circle would remain under a single administration, Charles V in the following year promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 which declared the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands a single indivisible possession not to be divided in future inheritance.

The consequence of these attempts at reducing the fragmentation of the government of the Holy Roman Empire was the separation of the Netherlands as an entity apart from the remaining empire, forming an important step towards the formation of the Dutch Republic in 1581.

References

- Rachfahl, Felix (1900). "Die Trennung der Niederlande vom deutschen Reiche". Westdeutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst. 19: 79–119.

- Mout, Nicolette (1995). "Die Niederlande und das Reich im 16. Jahrhundert". In Press, Volker; Stievermann, Dieter. Alternativen zur Reichsverfassung in der Frühen Neuzeit?. pp. 143–168.

- Dotzauer, Winfried (1998). Die deutschen Reichskreise (1383–1806). Geschichte und Aktenedition. Steiner. pp. 390 ff., 565 ff. ISBN 3-515-07146-6.