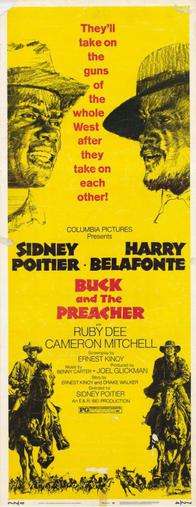

Buck and the Preacher

| Buck and the Preacher | |

|---|---|

Film Poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Poitier |

| Produced by | Joel Gilckman |

| Written by | Ernest Kinoy |

| Starring |

Sidney Poitier Harry Belafonte Ruby Dee |

| Music by | Benny Carter |

| Cinematography | Alex Phillips Jr. |

| Edited by | Pembroke J. Herring |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Buck and the Preacher is a 1972 American Western film released by Columbia Pictures, written by Ernest Kinoy and directed by Sidney Poitier. Poitier also stars in the film alongside Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee.

This is the first film Sidney Poitier directed. Vincent Canby of The New York Times said Poitier "showed a talent for easy, unguarded, rambunctious humor missing from his more stately movies".[1]

This film broke Hollywood Western traditions by casting blacks as central characters and portraying both tension and solidarity between African Americans and Native Americans in the late 19th century. The notable blues musicians Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, and Don Frank Brooks performed in the film's soundtrack, composed by jazz great Benny Carter.[2]

Plot

Set shortly after the American Civil War, Buck and the Preacher follows a former soldier named Buck (Sidney Poitier) as he leads wagon trains of African Americans from Louisiana west to the unsettled territories of Kansas. In order to ensure safe passage and food for his company, Buck has, for one, learned to negotiate with the Native Americans in the area. He pays them, and in turn they allow him to kill buffalo and pass through their land with specific time constraints. However, the natives are not the only factor to deal with.

A group of violent white men employed by plantation owners in Louisiana Delta have been tasked with raiding African American wagon trains and settlements to either scare them back to Louisiana or kill them. The raiders attempt to kill Buck by setting a trap at his home. However, he escapes and by chance meets Reverend Willis Oaks Rutherford (Harry Belafonte), a shady individual masquerading as a preacher. He forces the Reverend to switch horses with him. Although the Preacher initially had a desire to bring Buck to the raiders for a $500 reward, he eventually decides to work with Buck after seeing the carnage that the white men impose upon the African American travelers. With the aid of Buck's wife, Ruth (Ruby Dee), the protagonists do whatever it takes to get the wagon train west including robbing a bank and taking on an entire band of armed men.[3]

The film is set in the late 1860s in the Kansas Territory immediately following the American Civil War.

Cast

- Sidney Poitier as Buck

- Harry Belafonte as The Preacher

- Ruby Dee as Ruth

- Cameron Mitchell as Deshay

- Denny Miller as Floyd

- Nita Talbot as Madame Esther

- John Kelly as Sheriff

- Tony Brubaker as Headman

- Bobby Johnson as Man Who Is Shot

- James McEachin as Kingston

- Clarence Muse as Cudjo

- Lynn Hamilton as Sarah

- Doug Johnson as Sam

- Errol John as Joshua

- Jullie Robinson as Indian Renzi

Production background

Buck and the Preacher was one of the first films directed by an African American and to be based on a band of African Americans fighting against the White majority. Poitier directed the film and it was produced by Belafonte Enterprises, Columbia Pictures Corporation, and E & R Productions Corp. The film was filmed in Durango, Mexico, as well as in Kenya. It was released in the United States in 1972.

Poitier wasn’t originally slated as the director of the film. Joseph Sargent, who was known for being a western director, left the project because of some disagreements he had with some of the cast. Even though this would be the first feature he directed, Poitier assumed the role of director.[4] It took Poitier 45 days to shoot the film, and he edited the film during the shooting of The Organization, which he starred in.[5]

In regards to how Poitier felt directing, he stated, “I rolled my camera for the first time. I tell you, after three or four takes of that first scene, a calm came over me. A confidence surged through my whole body… and I, as green as I was, had a touch for this new craft I had been courting from a distance for many, many years.”[6]

Themes

Black Power

Black Power themes can be seen throughout the film. Many allegorical parallels can be drawn between the film’s plot and the main tenets of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.[7]

The violence of the marauders preventing the former slaves from settling their own land parallels the housing and property ownership issues of the 1960s. Additionally, the film comments on the systemic racism of the twentieth century by depicting a conversation between the leader of the marauders and a sheriff. Essentially, the point of the conversation is to illustrate that although there are laws in place to prevent racism and violence, the lack of enforcement of those laws makes them useless, in effect.[7]

The film also has themes shared by other Blaxploitation films in regards to its depiction of white people and how they interact with African Americans. Not only does the film depict white people as being sadistic, there is a specific scene in which Preacher uses a racist stereotype to fool the night riders into a sense of comfort. He improvises an over-the-top sermon to get the white men to laugh and let their guards down, and as soon as they do, Buck enters and kills everyone at the table.[8] This usage of racist stereotypes by oppressed people can be seen in other Black Power films such as The Spook Who Sat by the Door.[9]

Exodusters

Following the Civil Car, around 1879, African Americans in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Tennessee fled to Kansas seeking work and new lives away from the South. These migrants are known as “Exodusters.” [10] While there was work for them in the South and slavery had technically ended, the powerful white leaders of Southern states did all they could to prevent African Americans from owning land. These lawmakers also created sharecropping which, in effect, continued slavery. Also, the Exodusters had no interest in sharecropping or growing cotton or other cash crops for the white people who were once slave owners. The work they sought in Kansas was subsistence farming.[10]

With the independence of African Americans in the South came a violent reaction from Southern whites. The scarce law enforcement of rural areas mixed with Confederates’ bitterness about their loss of the Civil War, which was frequently blamed on African Americans, lead to groups of former Confederate soldiers raiding settlements of former slaves trying to make their own way. These marauders would steal supplies, horses, food, and destroy anything they didn’t take. This violence only gave the Exodusters more reason to flee to Kansas.[10]

Reception

According to Poitier, the film was not an immediate success financially. The film was made on a budget of $2 million and Poitier claimed that it broke even at the box office. In fact, the poor financial reception resulted in Poitier losing a film deal with Columbia Pictures.[7]

Critics were somewhat split in their reviews. Gordon Gow, a critic for Films and Filming, said that the movie was “breezy stuff and highly entertaining.” He went on to say that Belafonte’s performance was humorous even though it was somewhat over-the-top for the overall historical realism that the film is going for.[4]

Other reviews were not so positive. Writers for Motion Picture Guide focused more on the negative stereotypes presented in the film. “Stereotypes abound in this foolish, witless western, a production misusing the fine black talent in its cast."[4]

The initial lackluster response from audiences may have been caused by how different Buck is than typical Blaxploitation heroes such as Shaft and Coffy who live in contemporary society. The old west setting may have been too far removed from the African American audiences viewing the film. Additionally, the fact that white heroes were typically the centerpieces of American westerns may have also contributed to the foreignness of the film to its target audience.[11]

Conclusion

No sequels were made to Buck and the Preacher. However, both Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte remain highly respected in the American film industry, as well as best friends.[12]

Not only Poitier did establish himself as a director with this film, but he established his style of filmmaking that can be seen throughout most of his work. He favors close-ups, long takes, and long shots. In all three, the decisions are made to benefit the performers: Close-ups allow actors to be subtle with their performances, while long takes and long shots give them the ability to improvise.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (1991-02-08). "Critic's Notebook; Black Films: Imitation Of Life?". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ↑ Pareles, Jon (1996-02-19). "Brownie McGhee, 80, Early Piedmont Bluesman". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ↑ Buck and the Preacher, 1972, dir. Sidney Poitier

- 1 2 3 Berry, Torriano; Berry, Venise T. (2001). No eBook available Amazon.com Barnes&Noble.com Books-A-Million IndieBound Find in a library All sellers » Get Textbooks on Google Play Rent and save from the world's largest eBookstore. Read, highlight, and take notes, across web, tablet, and phone. Go to Google Play Now » My library My History Books on Google Play The 50 Most Influential Black Films: A Celebration of African-American Talent, Determination, and Creativity (illustrated ed.). Citadel Press. p. 126. ISBN 0806521333.

- ↑ Goudsouzian, Aram (January 20, 2011). Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon (illustrated ed.). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p. 339. ISBN 9780807875841.

- ↑ Raymond, Emilie (June 8, 2015). Stars for Freedom: Hollywood, Black Celebrities, and the Civil Rights Movement. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. p. 208. ISBN 0295806079.

- 1 2 3 4 Corson, Kieth (March 22, 2016). African American Directors after Blaxploitation, 1977-1986 (illustrated ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 9781477309087.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael K. (January 8, 2014). Hoo-Doo Cowboys and Bronze Buckaroos: Conceptions of the African American West. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781628469073.

- ↑ Reich, Elizabeth (Fall 2012). "A New Kind of Black Soldier: Performing Revolution in The Spook Who Sat by the Door". African American Review. 45 (3).

- 1 2 3 Painter, Nell Irvin (1992). Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction (illustrated, reprint ed.). New York City, New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393009514.

- ↑ Donalson, Melvin (January 1, 2010). Black Directors in Hollywood. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292782242.

- ↑ Blow, Charles M. (2017-02-20). "Opinion | Harry and Sidney: Soul Brothers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-12-13.