Bucareli Treaty

The Bucareli Treaty (Spanish: Tratado de Bucareli), signed in 1923, was an agreement attempting to resolve issues in Mexico–United States relations. In Spanish, it was named the "Convención Especial de Reclamaciones" (English: Special Convention of Claims), and it covered the losses sustained by citizens and companies of the United States in the Mexican Revolution.[1][2][3][4][5]

The treaty sought to channel the demands of U.S. citizens for damage to their property caused by the strife of the Mexican Revolution between 1910 and 1921.[2][3][4] The negotiations were conducted in a Mexican government building at 85 Avenida Bucareli (therefore the treaty nickname) between May 15 and August 13, 1923. The treaty was signed by President Alvaro Obregon primarily to obtain diplomatic recognition from the U.S. government, but it was never approved by the congresses of either country.[6] The treaty was canceled shortly afterward by President Plutarco Elías Calles.[7]

History

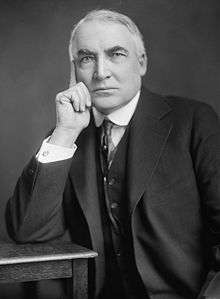

The situation of Mexico at the time was marked by political instability and constant military revolts. Part of the relative weakness of government of Alvaro Obregon came from the fact that the United States had not recognized its post-revolutionary regime.[8] The Constitution of 1917, with a strong socialist and nationalist influence, had hurt many U.S. interests.[4] Therefore, President Warren G. Harding refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Obregon government, and his government demanded the repeal of several articles of the new constitution or at least that they not be applied to American companies.[3] For Obregon, U.S. recognition of his government was a priority, to stave off another armed conflict.[2][9]

Obregon considered that foreign direct investment was necessary to rebuild the Mexican economy.[10] The U.S., however, wanted a treaty whereby Mexico would guarantee the rights of property of U.S. citizens living in Mexico, as well as that of American oil companies.[2][3][4][10] The oil problem stemmed from Article 27 of the Mexican constitution, which stated that Mexico was in direct control of everything on Mexican soil.[7]

The conditions demanded by the U.S. were:[2][3][4][11]

- Specify in the content of Article 27 of the Constitution the legal situation of oil industry and agricultural properties of foreigners.

- Resume payment of external debt, which had been suspended during the government of President Venustiano Carranza.

- Pay compensation to foreigners for damages to themselves or their property during the revolution.

The Mexican Supreme Court of Justice determined that Article 27 would not be retroactive for the oil industry. Regarding the resumption of external debt payments, Obregon tried to obtain funds through new taxes on oil, but the companies halted their production, a tactic that forced the government to repeal the tax.[12]

Agreement

The treaty, signed by Obregon on August 13, 1923, stipulated that:[2][10][13]

- Any agricultural property expropriated from Americans, no greater than 1755 hectares, would be paid for with bonds.

- For properties that exceed that measurement, the payment would be immediate and in cash.

- A commission would be created to review claims pending since 1868; claims arising out of the Revolution would be resolved separately.

- Regarding oil, Article 27 was deemed not retroactive for the companies which had acquired their leases before 1917, allowing them to continue exploiting the oil freely.

Claims must be met for a period of two years and had to be processed for five years from the signing of the treaty. However, the treaty lacked legal validity because it was not approved by the congresses of the two signatory countries, being in a "gentleman's agreement", which involved only to Obregon but not their successors, despite of this, the government of Obregon was recognized by the U.S. government.[10]

Former interim president Adolfo de la Huerta, who was in Obregon's cabinet as Secretary of the Treasury, asserted that the treaty violated the national sovereignty and subjected Mexico to humiliating conditions".[13] De la Huerta accused Obregon of treason against the nation, while simultaneously, de la Huerta was accused of incompetence in the performance of his duties and he was made responsible for financial plight. De la Huerta resigned and moved to Veracruz, from where he launched a manifesto that set off the Rebelión Delahuertista in December 1923.

A common idea in Mexico says that the treaty forbade Mexico to produce specialized machinery (engines, aircraft, etc.),[14] so presumably, Mexico delayed for many years the development of its economy.[15] It has been argued that during the period between 1910 and 1930, civil wars, multiple military coups and rebellions devastated the industries in Mexico and stopped higher education, research and technological development, while social and political instability drove off the foreign investments.[16] The Revolution did not, in fact, destroy the industrial sector, either its factories, extractive facilities, or its industrial entrepreneurs, so that once the fighting stopped in 1917, production resumed.[17] The full text of the Bucareli Treaty, published after it was signed, verifies the absence of prohibitions on technology or anything similar.

Purpose

Plutarco Elías Calles

When Plutarco Elías Calles took office on December 1, 1924, one of the main points of contention between the U.S. and Mexico still was oil. Calles quickly rejected the Bucareli Treaty and began drafting a new oil law that strictly fulfill the Article 27 of the Constitution.[7] The U.S. government's reaction was immediate, U.S. ambassador in México, James R. Sheffield called Calles a "communist", and the U.S. Secretary of State Frank Billings Kellogg issued a threat against México on June 12, 1925.[7]

Public opinion in United States turned against Mexico when the first embassy of the Soviet Union in the world, was opened in México;[18] time that the Soviet ambassador said that no country in the world shows more similarities to the Soviet Union and México. After this, members of the U.S. government considered Mexico to be the second bolshevik country on earth, and they began to call it "Soviet México."[7][19]

The debate on the new oil law was in 1925, with U.S. interests opposed to any initiative. On 1926, the new law was enacted. On January 1927, the Calles government canceled permits to oil companies that did not meet the law.[7] México managed to avoid the war through a series of diplomatic maneuvers. Shortly after, a direct telephone hotline was established between President Plutarco Elías Calles and President of the United States Calvin Coolidge, U.S. Ambassador in Mexico, James Sheffield was replaced by Dwight Morrow.[7] On March 18, 1938, after a series of contempt for foreign oil companies, President Lázaro Cárdenas del Río decreed the Mexican oil expropriation, creating PEMEX.[20]

References

- ↑ Fechas Históricas de México, por FERNANDO OROZCO LINARES, PANORAMA EDITORIAL, S. A., 1992

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Trujillo Herrera, Rafael (1966). Adolfo de la Huerta y los Tratados de Bucareli. Librería de Manuel Porrúa.

- 1 2 3 4 5 GONZÁLEZ RAMÍREZ, MANUEL (1939). Los llamados Tratados de Bucareli: México y los Estados Unidos en las convenciones internacionales de 1923. Mexico: Editorial FÁBULA. p. 441.

- 1 2 3 4 5 General Claims Commission (Mexico and United States). "General Claims Commission (Mexico and United States): An Inventory of its Decisions Held by the Benson Latin American Collection". Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ↑ 43 Stat. 1722. Available on Wikisource.

- ↑ "13 de agosto de 1923. - Firma de los tratados de Bucareli" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 KRAUZE, Enrique: "Plutarco Elías Calles, reformar desde el origen", en la serie "Biografía del Poder", México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1987.

- ↑ Howard F. Cline, The United States and Mexico. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1961, p. 204.

- ↑ Antonio Pérez Manzano (Marzo 18 de 2010). "Doctrina Estrada: herida de muerte". Excelsior. Retrieved 2010-03-29. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Tratado de Bucareli

- ↑ Bazant, Jan (1981). Historia de la deuda exterior de Mexico. Mexico: El Colegio de Mexico. p. 191.

- ↑ México y Estados Unidos firman los tratados de Bucareli. (in Spanish) Memoria Politica de Mexico. Quote: "Para reanudar el pago de la deuda externa, Obregón intentó obtener fondos mediante impuestos al petróleo, pero las empresas petroleras se opusieron, detuvieron la producción y obligaron al gobierno a derogarlos. Entonces negoció la deuda externa con Estados Unidos".

- 1 2 Memorias de Adolfo de la Huerta

- ↑ Mateos Santillán, Juan José (2017). Como vender al país y quedar a deber. De los Tratados de Bucareli 1923 a Donald Trump. México. pp. Loc227.

- ↑ Asdrúbal Flores (2003). Protocolo Secreto De Los Tratados De Bucarelli (Ficción). Mexico, D.F.: Galileo Ediciones. p. 258. ISBN 968-5429-02-2.

- ↑ ROSAS, Alejandro: "Mitos de la historia mexicana. De Hidalgo a Zedillo", México, Editorial Planeta, 2006. ISBN 970-37-0555-3

- ↑ Stephen Haber, "Assessing the Obstacles to Industrialization: the Mexican Economy, 1830-1940," Journal of Latin American Studies vol 24, No. 1 (Feb. 1992) p. 27

- ↑ "Embajada de México en: FEDERACIÓN DE RUSIA" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ RICHARDS, Michael D. Revolutions in World History p. 30 (2004 Routledge) ISBN 0-415-22497-7

- ↑ "18 de marzo de 1938. Aniversario de la Expropiación Petrolera" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2010-09-21. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

Bibliography

- CASASOLA, Gustavo: "Historia Gráfica de la Revolución Mexicana. Tomo 1", Madrid, España, Editorial Trillas, 1992. ISBN 968-24-4524-8

- "Seis siglos de historia gráfica de México, tomo 12", México, Editorial Trillas, 1976. ISBN 968-7013-00-1

- ESQUIVEL MILÁN, Gloria — colaboración con Enrique Figueroa Alfonso —: "Historia de México", Oxford, Editorial Harla, 1996. ISBN 970-613-092-6

- FUENTES MARES, José: "Historia Ilustrada de México, de Hernán Cortés a Miguel de la Madrid. Tomo II", México, Editorial Océano, 1984. ISBN 968-491-047-9

- KRAUZE, Enrique: "Álvaro Obregón, el vértigo de la victoria", México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1987. ISBN 968-16-2785-7

- MORENO, Salvador — colaboración con Amalia Silva —: "Historia de México", México, Ediciones Pedagógicas, 1995. ISBN 968-417-230-3

- ROSAS, Alejandro: "Mitos de la historia mexicana. De Hidalgo a Zedillo", México, Editorial Planeta, 2006. ISBN 970-37-0555-3

- SILVA CAZARES, Carlos: "Álvaro Obregón", en la serie "Grandes protagonistas de la historia mexicana", México: Planeta DeAgostini, 2002. ISBN 970-726-081-5

- TREVIÑO, Héctor Jaime: "Historia de México", Monterrey, Ediciones Castillo, 1997. ISBN 970-20-0019-X

- VASCONCELOS, José: "Breve historia de México", México, Editorial Trillas — colección "Linterna mágica" —, 1998. ISBN 968-24-4924-3

- VILLALPANDO, José Manuel — colaboración con Alejandro Rosas —: "Los Presidentes de México", México, Editorial Planeta, 2001. ISBN 970-690-507-3

- MARTIN MORENO, Francisco: "México Acribillado", México, Editorial Alfaguara, 2008. ISBN 978-970-58-0456-4

- Moreno Suarez, Adolfo; I. Paniagua Arredondo, Jose. Los Tratados de Bucareli: Traicion y Sangre Sobre Mexico.

- Trujillo Herrera, Rafael (1966). Adolfo de la Huerta y los Tratados de Bucareli. Librería de Manuel Porrúa.

Documentaries

- Álvaro Obregón, El Vértigo de la Victoria. Dir. Arturo Pérez Velasco, 1999.

- México: Revolution and Rebirth. History Channel, 1999.